The U.S. Navy’s forthcoming force structure review may call for a fleet with up to 534 ships and submarines, including various kinds of unmanned vessels. The is far bigger than the existing Congressionally-mandated goal of a 355-ship fleet, which has long proven to be a struggle for the service to achieve. Plans for an even larger force could run into significant budgetary, recruiting, sustainment, and other hurdles.

Defense News

got the scoop on the expanded fleet concepts after obtaining draft copies of naval force structure studies that the Pentagon’s Office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) and the Hudson Institute think tank produced for the Office of the Secretary of Defense. Those reports date back to April 2020 and were meant to present a proposed ideal fleet composition and plans for obtaining it by 2045. The Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff was also set to produce a study, the details of which remain unknown.

Those studies have since been evaluated, including through simulated wargames, and have been incorporated, at least in some part, into the Navy’s Future Naval Force Study, according to Defense News. This new force structure plan was originally expected to be completed sometime last year, but has been repeatedly pushed back. At present, the plan is to use this final study to inform the next shipbuilding plan, which will accompany the service’s budget request for the 2022 Fiscal Year, a public version of which should come out sometime between February and March 2021.

“The Future Naval Force Study is a collaborative OSD, Joint Staff and Department of the Navy effort to assess future naval force structure options and inform future naval force structure decisions and the 30-year shipbuilding plan,” Navy Lieutenant Tim Pietrack, a spokesperson for the service, told Defense News. “Although COVID-19 has delayed some portions of the study, the effort remains on track to be complete in late 2020 and provide analytic insights in time to inform Program Budget Review [FY] 22.”

Changes to carrier, other surface vessel, and submarine fleets

The proposed fleets from both CAPE and Hudson have significant differences compared to the Navy’s existing structure, which currently has around 290 ships and is expected to grow to 301 ships by the end of this year. Both of the plans notably recommended cutting the total number of supercarriers to nine from the service’s current total of 11, which includes the 10 Nimitz class carriers and the first-in-class USS Gerald R. Ford.

It is also worth noting that, by law, the Navy is compelled to always be working toward having a dozen active supercarriers, something that would have to change for either of these plans to go into effect. Hudson’s proposal also included four smaller light aircraft carriers in addition to the remaining supercarriers, something the service was considering in April, but publicly said it was no longer exploring, at least in the near term, the following month.

CAPE also recommended a total of between 80 and 90 large surface combatants, a category that presently includes the Navy’s Arleigh Burke class destroyers and Ticonderoga class cruisers, while Hudson favored reducing these number of these types of ships The Arleigh Burkes and Ticonderogas account for 89 ships in the service’s present fleet. There has also been talk about a future Large Surface Combatant that could replace both types, but the Navy is still just in the process of crafting the basic requirements for this vessel.

The plan from CAPE called for around 70 small surface combatants, while Hudson proposed slashing that number to just 56. At present, the Navy’s two subclasses of Littoral Combat Ships (LCS) are the only vessels it operates in this category. At the end of the day, the Navy expects to have bought 38 Freedom and Independence class ships in total, some of which are already being retired.

The service is now also in the process of acquiring a new fleet of guided-missile frigates, presently referred to as FFG(X), which would also bolster the size of its small surface combat fleet. The first of these, at least, will be based on Italian shipbuilder Fincantieri’s European Multi-Purpose Frigate design, also known by the Franco-Italian acronym FREMM.

Both CAPE and Hudson were in favor of increasing the Navy’s number of attack submarines, but Defense News did not give the exact proposed submarine fleet totals for either study. The service is already looking to begin development of a new attack submarine with capabilities more akin to its trio of advanced Seawolf class boats, which were originally designed primarily as hunter-killers, rather than the more multi-purpose Virginia class.

A shakeup in amphibious and support ships

Defense News said that the proposals from CAPE and Hudson called for between 15 and 19 amphibious warfare ships, with CAPE’s plan including 10 large amphibious assault ships, such as the Wasp and America classes, while Hudson’s notional fleet had only five.

This category also includes dock landing ships, such as the San Antonio class, and these figures represent what would a major reduction in the number of traditional amphibious ships in the Navy’s overall fleet. This is in line with new radical concepts of operation emanating from the U.S. Marine Corps under its present Commandant General David Berger, who has called for a major shift away from long-standing views of amphibious warfare.

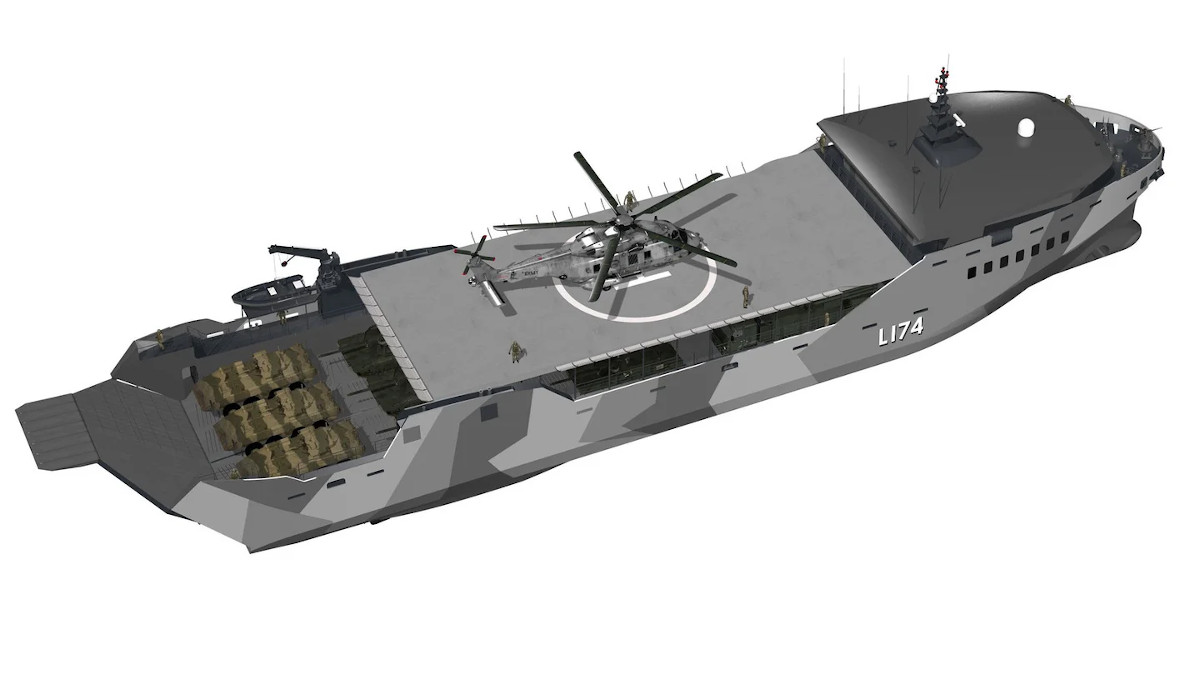

As such, CAPE and Hudson included between 20 and 26 Light Amphibious Warships (LAW) in their proposed fleets, a type of ship that the Navy is now working to acquire based on requirements from the Marines, which you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone piece. The Navy has publicly said it could buy as many as 30 LAWs.

Both plans included significant increases in the total number of logistics and support ships in the Navy. This included adding between 19 and 30 new “future small logistics” ships, which could potentially be a type of offshore support vessel-type ship, and increasing the number of fleet oilers, ships able to refuel conventionally powered ships, from 17 to between 21 to 31. Hudson’s proposal specially called for adding 19 command and support ships, as well. This is a category that presently includes an array of specialized vessels within the Navy, including its two Blue Ridge class command ships, Spearhead class expeditionary fast transports, expeditionary sea bases and transfer dock ships, and other logistics vessels.

New unmanned fleets

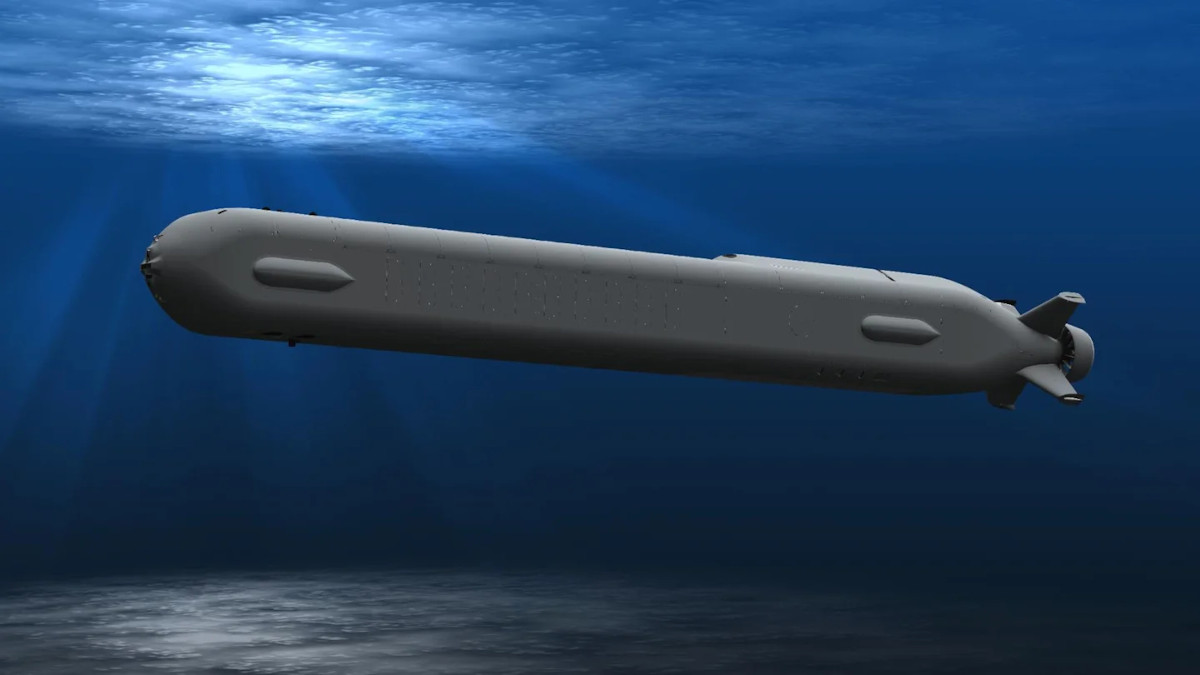

By far, the most significant additions in both plans are dozens of unmanned surface vessels (USV), including proposed “large” types that are the size of traditional corvettes, and large unmanned undersea vehicles (UUV). At present, the Navy does not formally include any vessels in these categories when talking about the size of its overall fleet. The notional fleets from CAPE and Hudson included between 65 and 87 large USVs and between 40 and 60 large UUVs.

The Navy, as well as the Office of the Secretary of Defense and the White House’s Office of Management and Budget, have all pointed to the inclusion of unmanned vessels as a way of finally reaching the existing 355-ship fleet goal. Their inclusion in the proposals from CAPE and Hudson meant that those notional fleets, which already included between 316 and 358 manned ships, would surge in size, with 534 total vessels between the maximum projected size among both studies.

In a vacuum, both of these proposals make sense in many ways, especially given U.S. military’s overall shift in focus to preparing for high-end conflicts and growing interest in distributed concepts of operation, including in the maritime domain, in recent years. The War Zone

has explored these developments on multiple occasions in the past.

In addition, as noted, the Marine Corps is undergoing a massive transition that includes a complete rethinking of how it conducts amphibious operations, especially in a distributed scenario in the Pacific region. The Navy, based on input from the Marines, and, to some extent, the Army, as well, has similarly begun re-evaluating how it might go about supporting ground forces during such operations.

On top of this, China is rapidly expanding the size and scope of its own naval capabilities, including adding significant numbers of new, advanced warships, including multiple aircraft carriers, and submarines. The most recent Pentagon report to Congress on Chinese military developments highlight naval modernization and shipbuilding as key areas where the People’s Liberation Army is making major advances that challenge traditional American superiority. This, in turn, has already prompted calls for more funding for new Navy ships.

Major hurdles ahead

While there are very real strategic realities and concerns that are clearly driving these fleet proposals, it’s unclear how realistic the Navy’s plans for getting to the existing 355-ship mark might be, let alone increasing that total to over 500 vessels. In 2019, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) assessed that the shipbuilding plan the Navy had released that year, which envisioned hitting 355 by 2034, would cost the better part of a trillion dollars to implement. The Navy itself had acknowledged that, after getting to its desired 355-ship fleet, it would then need $40 billion every year just to operate and maintain all those ships, some 30 percent more than it spends annually now.

Defense budgets always ebb and flow from year to year and it is especially hard, in general, to project how stable funding might be over a period of 15 to 25 years. Any basic budgetary concerns about this massive increase in the Navy’s overall fleet size are only exacerbated by the realities of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which has already led to a pronounced recession within the United States and major global economic downturn. The fact of the matter is that the service is having trouble paying for the fleets it has now.

The Navy, which has had trouble meeting recruiting goals in recent years, will still need to provide crews for the existing and new manned ships under both proposals, as well. The service has explored a variety of reduced and other novel crew concepts, as well as deployment mechanisms, to help ensure readiness with, at best, mixed results.

There is clearly a hope that a heavy emphasis on smaller ships with smaller crews and unmanned vessels could help defray many of these costs and reduce maintenance, infrastructure, and recruiting demands. However, the proposals from both CAPE and Hudson preserve much of the service’s existing surface and submarine fleets and call for the addition of more traditional manned ships, not all of which would be small.

There can only be questions about whether the Navy’s internal maintenance infrastructure, as well as the availability of contractors to provide additional shipyard capacity for repairs, could handle the increase in total ships, no matter how small they might be. The Navy’s shipyards are in notoriously poor condition. Although there have been some recent investments made to attempt to refurbish them, this reality has limited their ability to keep up with the workload they already have. Two years ago, the Government Accountability Office (GAO), notably assessed that the service has lost more than two decades of operational time across its attack submarine fleets to maintenance backlogs.

The Los Angeles class submarine USS Boise is something of a poster child for these issues and is presently set to return to service in 2023, after which it will have been out of commission over a need for routine repairs for approximately eight years. This submarine only entered service in 1992, meaning that it is set to have spent nearly a third of its career in the Navy so far sitting idle.

Glaring concerns about shipyard capacity, and the rest of the industrial base, apply to building any new ships for the Navy and keeping that construction on schedule. Cost overruns and delays, which are hardly unheard of in the service’s shipbuilding programs, could easily have negative cascading impacts on its overall force structure plans.

Pushback from Congress is something that has repeatedly undermined Navy shipbuilding plans, as well. So, there’s no guarantee that legislators will agree to fund whatever final proposal the Navy presents to them when asking for its 2022 Fiscal Year budget, either.

All told, while the studies from CAPE and the Hudson Institute are certain to be valuable additions to the continuing debate around the Navy’s future fleet structure and shipbuilding priorities, it very much remains to be seen how much, if any of these recommendations will be implemented any time soon.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com