The U.S. Navy has hired Boeing to build four Orca extra-large unmanned undersea vehicles, or XLUUVs. The service plans to use the Orcas to explore and refine future concepts of operation for underwater drones of this size, which could include gathering intelligence, emplacing or clearing naval mines, attacking other ships or submarines, conducting stand-off strikes, and more.

The Pentagon announced that the Navy had awarded Boeing the contract for the Orcas, worth $43 million, in its daily service-wide contracting announcement on Feb. 13, 2019. Separately, the Chicago-headquartered defense contractor said it is partnering with shipbuilder Huntington Ingalls on the project in a Tweet on Feb. 15, 2019.

“The Orca XLUUV will be modular in construction with the core vehicle providing guidance and control, navigation, autonomy, situational awareness, core communications, power distribution, energy and power, propulsion and maneuvering, and mission sensors,” the Pentagon announcement said. It “will have well-defined interfaces for the potential of implementing cost-effective upgrades in future increments to leverage advances in technology and respond to threat changes.”

In 2017, the Navy awarded XLUUV developmental contracts to both Boeing and Lockheed Martin. The latter firm had proposed a vehicle with a shape more in line with an enlarged torpedo.

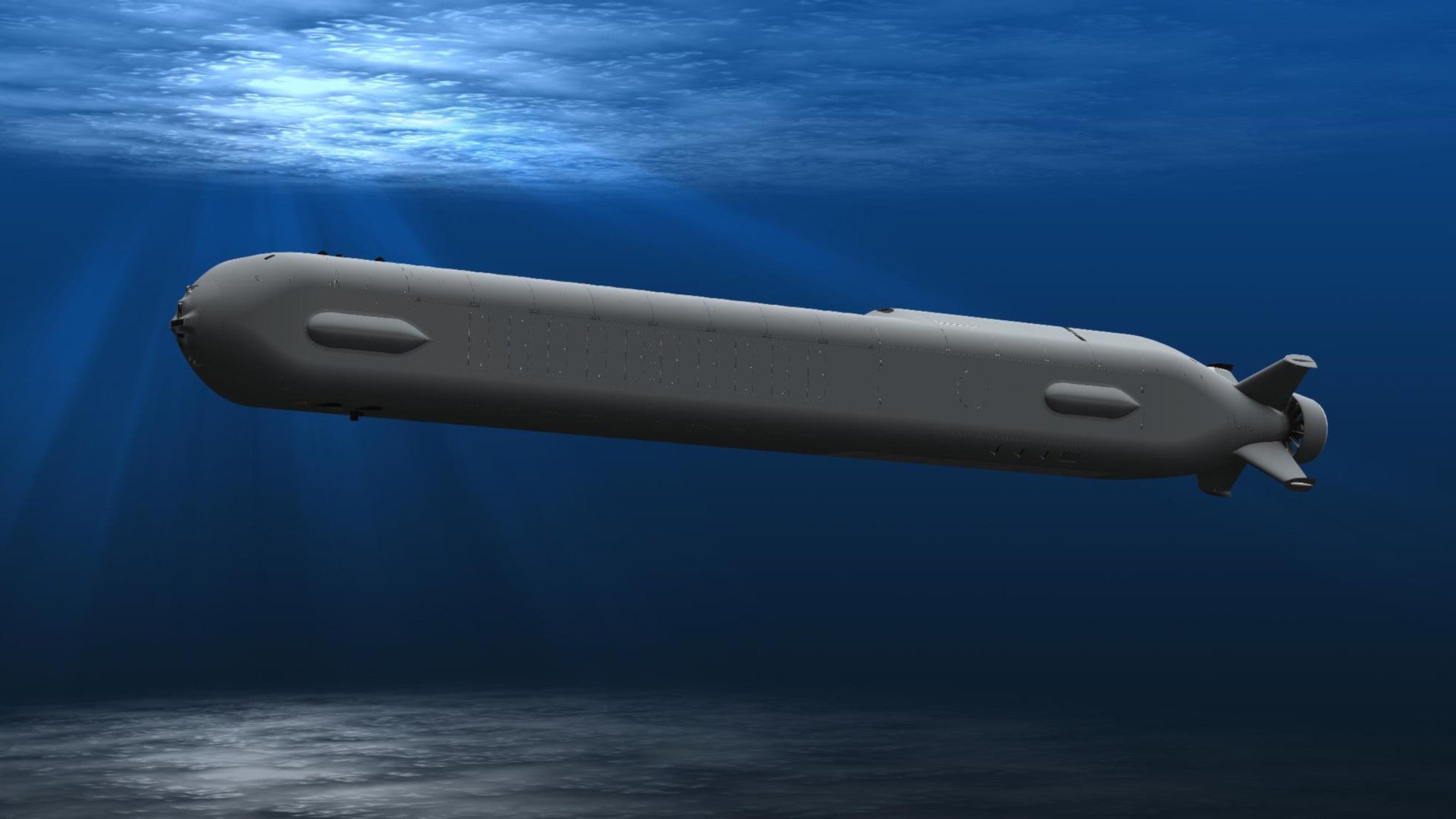

Boeing’s Orca design has a boxier hullform more akin to a small submarine and is derived from an earlier private venture known as Echo Voyager. This XLUUV was itself an evolution of previous work done the company had done on large unmanned undersea vehicles called Echo Seeker and Echo Ranger.

The most obvious difference between the Echo Voyager and the new Orca, at least based on Boeing’s concept art, is the replacement of the earlier undersea drone’s propeller with a shrouded propulsor. This improves propulsion efficiency and reduces noise, the latter factor being especially important for underwater military craft, where silence is essential to survival. Many modern military submarines, including the U.S. Navy’s Seawolf– and Virginia-classes, have similar propulsors for exactly this reason.

Otherwise, it looks likely that the new Orcas will borrow significantly from the 51-foot long, 50-ton Echo Voyager’s design, including its modular payload bays. The Orca’s basic performance may be similar, as well.

The diesel-electric Echo Voyager has a maximum speed of around nine miles per hour underwater and can dive to depths up to 11,000 feet deep. Its batteries give it range of more than 150 miles at a speed of around 3 miles per hour, before it needs to surface and use its air-breathing diesel generator to recharge.

Boeing has said that Echo Voyager could carry enough fuel to allow it to operate autonomously for up to six months at a time, covering total ranges of around 7,500 miles. With just one fuel module in its modular payload bays, it would still have a full range of more than 6,500 miles. It has its own sonar-enabled obstacle avoidance system, as well as an inertial navigation system.

Orca may also leverage experience Huntington Ingalls gained while working on its own large unmanned undersea vehicle project, called Proteus, in cooperation with Bluefin Robotics and Battelle. Proteus is a significantly smaller vehicle, though, at around 25 feet long, and is limited capability-wise compared to Echo-Voyager

.

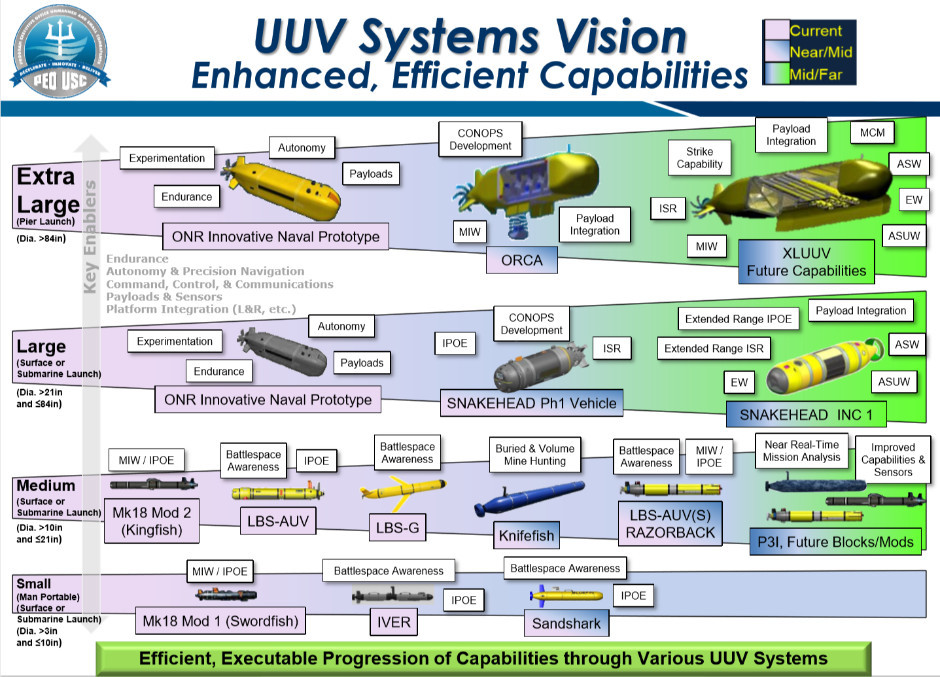

The range and payload capacity of Boeing’s earlier design would have already made it attractive to the Navy, which has been actively looking at potential missions for a drone submarine of this size since at least 2000. That year, the service issued its first unmanned undersea vehicle strategy white paper.

In 2004, it released a new Unmanned Undersea Vehicle “master plan.” As of 2011, there was reportedly yet another update to the overarching strategy, but it has remained classified. But public briefings since then have shown that the Navy’s plans for future XLUUVs remain largely unchanged.

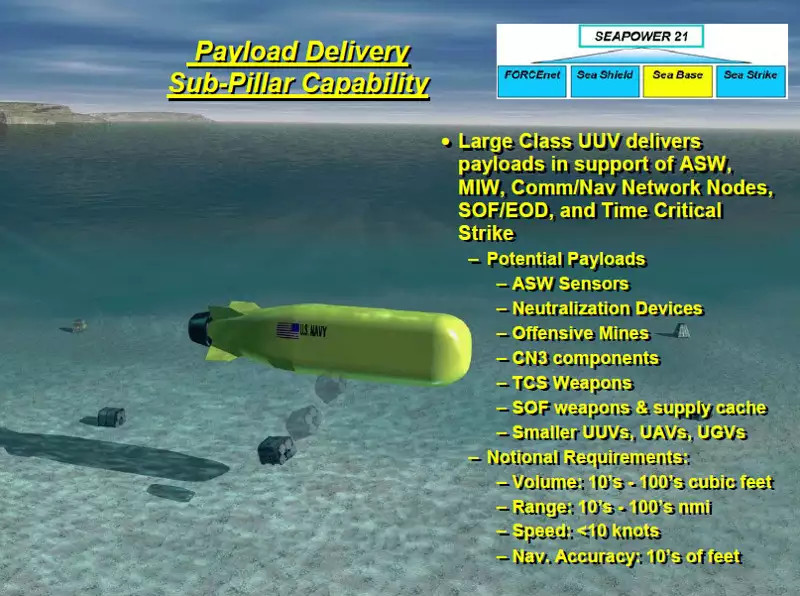

Orca’s immediate mission will likely be mine and counter-mine warfare. The threat of naval mines is only increasing and proliferating to even non-state actors. The Navy itself recognizes the value these weapons would have in various operational scenarios and is looking to expand its own capabilities in that regard, which you can read about more here.

The Navy already uses much smaller unmanned undersea vehicles to scout for hostile mines without necessarily having to put manned ships at risk. Even the relatively large Orca would be better able to get into harder to reach areas, especially narrow and shallow waterways, where traditional minesweepers simply may not be able to maneuver.

With their endurance and autonomy, multiple Orcas could help clear a broader area in less time, as well. Naval mine hunting and sweeping have historically been a slow and painstaking affair that would be especially difficult to do rapidly under enemy fire.

The ability of the Orcas to operate across extended ranges and do so autonomously and discreetly, means they offer a novel way to deploy mines, as well. The underwater drones could not only help set up maritime minefields quickly within strategic chokepoints, but they could also potentially penetrate into denied areas well away from conflict zones to threaten enemy ports, shipyards, and other facilities.

This could include seeding mines in rivers and canals, as well. This kind of distributed mine warfare could only hamper the free movement of hostile naval forces, disrupt maritime logistics chains, and otherwise force an opponent to diverse limited resources to protecting rear areas.

These same qualities also open up the potential for a far greater array of missions in the future. If Orca can slip into enemy territory to plant mines, it can also do so to gather intelligence, already a well-established mission for larger manned submarines. It might also be able to act as a decoy, mimicking the signature of larger ships or submarines. The Navy has expressed an interest in finding a way for XLUUVs to carry electronic warfare packages to otherwise blind enemy sensors to incoming threats, but it is hard to see how this would work unless they’re while running on the surface or very close to the surface.

Beyond that, there’s the possibility that the Orcas, or a follow-on XLUUV design, could carry weapons themselves to carry out attacks on surface ships or submarines. The Echo Voyager’s payload bay was already large enough to accommodate light and heavyweight torpedoes and Boeing says that design could accept external payloads, as well.

Combined with their autonomous capability and long range, packs of future XLUUVs networked together might also be able to persistently monitor and track potential threats, such as increasingly advanced Russia or Chinese submarines, holding them perpetually at risk across a broad region, such the Pacific. This is a mission the Navy has also envisioned for its future fleets of unmanned surface vessels. The service would require an underwater drone that could travel much faster than Orca to adequately perform this particular mission, though.

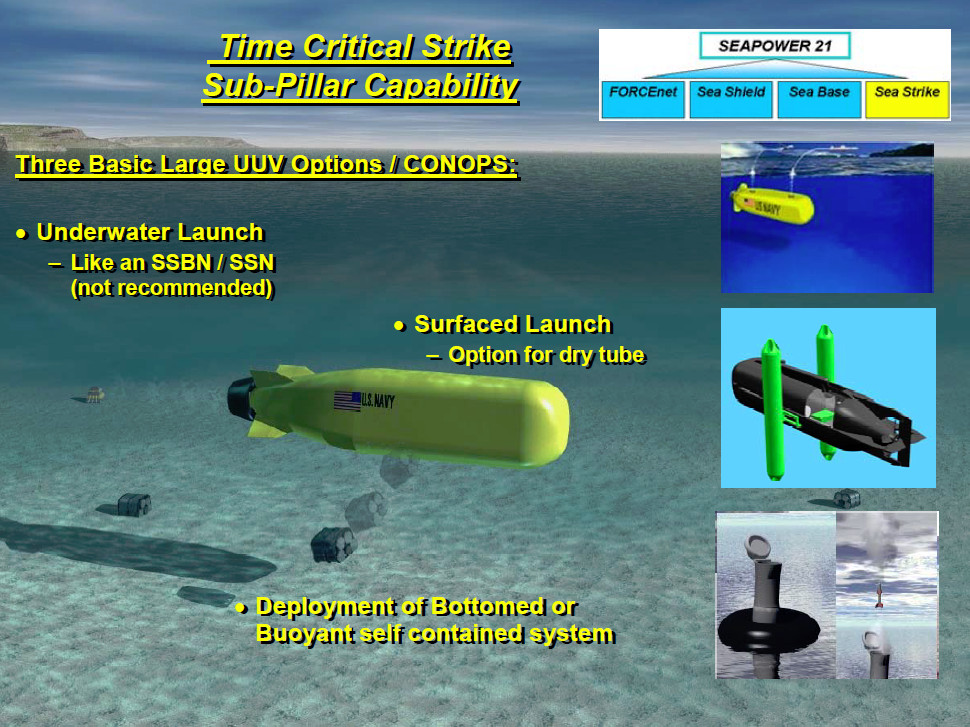

Lastly, Orcas might even eventually be able to launch strikes against targets ashore using stand-off cruise missiles. The Navy has described the ability for underwater drones to rapidly and discreetly position themselves close to a crisis area could make them valuable for time-sensitive strikes. It has also said that in the past that this particular mission set is a relatively low priority for XLUUVs.

The Navy’s ongoing plans for an over-arching network architecture, part of which is known as the Cooperative Engagement Capability (CEC), that will link all of its ships, submarines aircraft, and other assets, means that XLUUVs might perform any combination of these missions in direct cooperation with manned platforms, as well. It also means that a group of the underwater drones might include various versions carrying only sensors packages or just weapons, to maximum payload space while working together as a team.

The Orcas are also set to be a stepping stone in the Navy’s plans for what it calls Large Diameter Unmanned Undersea Vehicles (LDUUV) that submarines such as the Virginia-class could launch and recover much closer to the actual target area. The service is working on concepts for more robust submarine motherships as part of its Large Payload Submarine program, which you can read about more here.

There’s nothing to say that the Orca, or a future XLUUV, couldn’t work in conjunction with a submarine mothership either. Using a larger, manned platform to deploy any sort of large underwater drone would let designers trade range for added payload capacity. The arrangement would also allow the unmanned vehicle to loiter in and around the target area for a longer period f time, which could be very useful for intelligence missions.

The Navy does not have a fixed schedule for when XLUUVs like the Orcas might actually take on any of these missions operationally. But the four drone submarines will give the service the test force it needs to fully explore the capabilities of this new category of craft.

In 2017, it stood up its first ever dedicated unmanned undersea vehicle unit, Unmanned Undersea Vehicle Squadron One (UUVRON 1), specifically to take the lead in the development and testing of craft such as the Orca. The Pentagon’s contracting announcement says that Boeing and its partners will have built all four Orcas by 2022.

If this schedule holds, the next few years look to be an exciting time for the Navy and the development of new and impressive undermanned undersea capabilities.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com