The White House has told the U.S. Navy to come up with a proposal for counting at least some of its unmanned surface vessels and underwater vehicles among its so-called “Battle Force,” the portion of its fleet that has historically included larger, manned, traditional warships, such as aircraft carriers and destroyers, and supporting ships. This would be a major shift that would create a more realistic path for the service to meeting the ambitious Congressionally-mandated goal of a 355-ship Battle Force fleet and would help solidify the already growing importance of unmanned platforms in its future concepts of operation.

Bloomberg

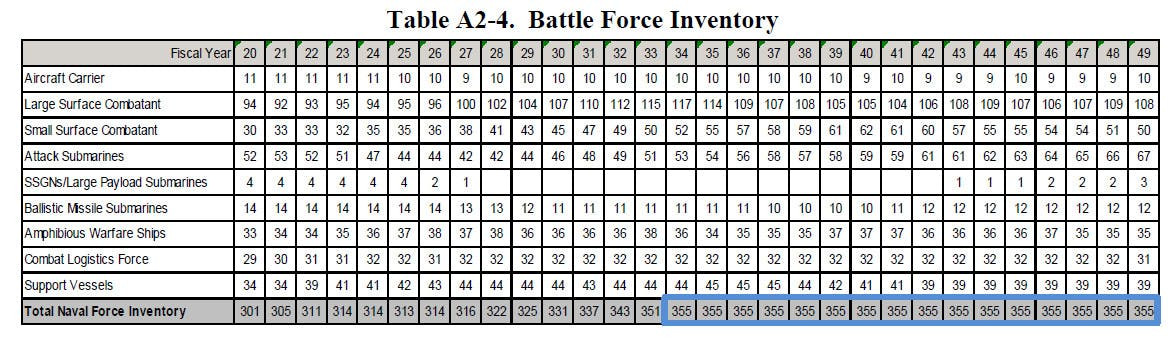

was first to report that the Office of Management and Budget, which sits under the Executive Office of the President of the United States, had issued the directive in a memorandum earlier this month. On Dec. 6, 2019, Acting Secretary of the Navy Thomas Modly had announced in a separate memo that finding a way to create a 355-ship Navy within the next 10 years was among his five immediate objectives. Earlier in the year, the Navy had already released a plan to reach that milestone by 2034. The service has around 290 ships in its Battle Force now and expects that to rise to 301 by the end of the 2020 Fiscal Year.

The OMB memo calls for a “legislative proposal to redefine a battleforce [sic] ship to include unmanned ships,” along with revised “capability and performance thresholds” for what vessels can get counted in that total. Getting Congress to agree to amend the existing legal language that enshrines the requirement for the Navy to have 355 ships to included unmanned platforms would help ensure that the plan receives the necessary budgetary support in the coming years.

It’s important to note that what OMB is asking for isn’t guaranteed to get Congress’s approval, but it does indicate that the Navy is increasingly looking at unmanned surface vessels and underwater vehicles as both a very real and economical way to expand its overall force structure and as functionally important components of what will be increasingly distributed operations in the future, something the War Zone has highlighted on a number of occasions in the past.

There have already been indications that the Navy has been moving in this direction with regard to the definition of the Battle Force. Modly’s Dec. 6 memo even had strong hints of this by calling for a “greater global naval power, within 10 years”, with “355 (or more) ships, Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs,) and Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs).”

Modly, in his previous capacity as Undersecretary of the Navy, had already been among those to question whether a 355-ship fleet made up of traditional vessels still made sense and whether it might be necessary to change long-standing definitions around the Battle Force to better reflect modern realities and technologies. “We have a goal of 355, we don’t have a plan for 355. We need to have a plan, and if it’s not 355, what’s it going to be and what’s it going to look like?” he said on Dec. 5, just a day before issuing his memo.

It’s hard to see how else Modly could even realistically envision getting to 355 ships by 2030 with the current definitions. The plan the Navy detailed in March about how it expected to meet this goal within the next 15 years was already questionably ambitious and extremely costly, with little flexibility for fluctuations in shipbuilding schedules or budgets, something the War Zone explored in-depth at the time. In October 2019, a report from the Congressional Budget Office showed that the total costs could be even higher than expected.

The Navy has already been laying the groundwork for its future unmanned fleets, notably creating Surface Development Squadron One in May, which has the job of exploring new naval surface warfare tactics techniques and procedures, including manned-unmanned teaming. The unit, which you can read about more in this past War Zone story, will eventually be the home of the Navy’s first two Sea Hunter experimental drone ships, along with manned vessels including all three Zumwalt class stealth destroyers, two of which are in service now, and the first two examples of both the Freedom and Independence class of Littoral Combat Ships (LCS). The Navy had already relegated those latter four ships to training and test roles.

In 2017, the Navy had also stood up Unmanned Undersea Vehicle Squadron One at the Naval Undersea Warfare Center in Keyport, Washington to perform the same general mission, but with regards to unmanned underwater vehicles. As of November, the service was working toward establishing Unmanned Undersea Vehicle Squadron Two, which will be base don the East Coast.

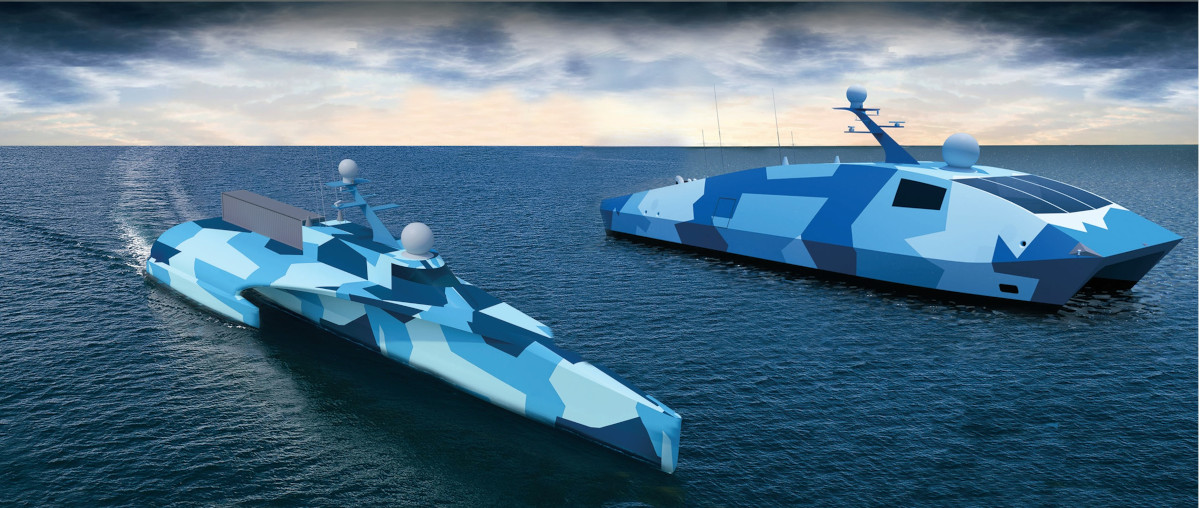

In December 2018, the Navy issued a request for proposals for an actual production Medium Unmanned Surface Vessel (MUSV) design. The twoSea Hunters, which are 132 feet long and displace around 145 tons, are supposed to provide a stepping stone to the operational MUSVs, which will be a similarly-sized craft.

Five months later, the service released another announcement asking for proposals for a Large Unmanned Surface Vessel (LUSV), which will be a significantly larger 2,000-ton displacement design. The Navy is already testing unmanned ships of a similar size, in cooperation with the Office of the Secretary of Defense’s Strategic Capabilities Office (SCO), as part of the Ghost Fleet Overlord program. The second phase of those experiments, which you can read about in more detail in this previous War Zone story, began in October.

On the unmanned undersea vehicle front, the Navy announced in February 2019 that it had hired Boeing to build a fleet of Orca large displacement drone submarines. The initial order is for four Orcas, with the last to be delivered in 2022. You can read all about the Orca initiative here.

This all rightly reflects the Navy’s growing acceptance that it simply will not be able to meet all of its operational demands in an economical fashion by solely using manned ships. This is a reality that will only become more pronounced as technology improves and ships and submarines, as well as their various systems, become ever more expensive. It’s one that has also been increasingly impacting planning for what future air and ground forces will look like, and the increasing integration of manned-unmanned teaming into the concepts of operations to go along with them, as well.

Whether or not Congress will be swayed remains to be seen. The latest annual defense policy bill, or National Defense Authorization Act, covering the 2020 Fiscal Year, which President Donald Trump is set to sign into law today, calls for reduced funding for both the Large and Medium Unmanned Surface Vessel programs. An unnamed source told Defense News that this was, in part, linked to backlash from legislators to a curious and ultimately abortive plan to retire the Nimitz class aircraft carrier USS Harry S. Truman early ostensibly in order to free up funds for, among other things, unmanned platforms.

“In view of uncertain LUSV concepts of operations, requirements, technical maturity — including many [first-of-a-kind capabilities] — the contrast between a proven aircraft carrier and its air wing and unproven unmanned surface vessels is stark,” the source said to Defense News.

The Navy had wanted money to buy two LUSVs this fiscal cycle, but lawmakers have notably rolled those plans back to just one. The service still hopes to purchase as many as 10 LUSVs in the next five years.

“Now, I’m not sure when we’re looking at a scenario where we’re dealing with a great power like China or Russia, where we’re going to have distributed responsibilities, whether that’s the right strategy for us,” Then-Undersecretary Modly had said in October of 355 ship fleet with traditional warships. “As technology advances and we have the ability to have fairly large unmanned platforms out there that have significant lethality, do we include them in our ship force count?”

All told, the final answer to that question, at least according to the Navy, looks more and more likely to be yes.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com