The COVID-19 pandemic has thrust the topic of “continuity of government,” plans in place to ensure critical elements of the U.S. government can keep functioning in the midst of an extreme crisis, back into the general public consciousness. It has also sparked renewed interest in the hardened, underground facilities where those personnel would work, such as the U.S. military’s “underground Pentagon” at Raven Rock, which you can read about more in this past War Zone feature. Had the U.S. government made different decisions during the Cold War, some of these teams might be sheltering inside a massive, very deeply buried bunker unlike any on earth, intended to shrug off direct impacts from nuclear bombs with huge yields of hundreds of megatons.

In January 1962, Charles Hitch, then the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), sent a memorandum regarding a proposed Deep Underground Command Center (DUCC) to then-Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. The plan was to construct “a ‘superhard’ command post easily accessible to the NCA [National Command Authority] and designed for minimum dislocation or interruption of official routines,” according to an official U.S. military historical review of command and control architecture from 1960 to 1977. The National Command Authority refers to the highest possible source of orders for American forces, the only mechanism by which a nuclear strike can be ordered, which consists of the President and the Secretary of Defense, as well as the approved deputies that would take their place if either of them were to be killed or otherwise incapacitated.

“The center could include an office where people, such as yourself, could conveniently spend a day every week or two to conduct business almost as usual and be in a position to assume National Command in the event of a no-warning attack on Washington,” Hitch wrote to McNamara.

It’s not entirely clear where the DUCC proposal first originated. A 1975 study of the evolution of U.S. strategic command, control, and early warning capabilities that the Institute for Defense Analysis (IDA) think tank had conducted for the Department of Defense, said it made “no attempt … to track the origins and development of the idea.” IDA’s researchers did note they had located a document that personnel within the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)’s Programming Office had prepared ahead of Hitch’s memo to McNamara.

IDA had also found consistencies in the design parameters between the DUCC and a U.S. Air Force Strategic Air Command (SAC) proposal for a Deep Underground Support Center (DUSC). SAC had also explored the DUSC concept in 1962, the year after it began building the Cheyenne Mountain Air Force Station bunker complex under the mountain of the same name, which you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone story.

The U.S.-Canadian North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) had also considered building extremely hardened Super Combat Centers in the late 1950s to house ground-controlled interception systems, known as the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE), which you can read about more in-depth in this previous War Zone piece. NORAD had canceled those plans in 1960.

Whatever the actual source of the DUCC plan was, it is clear that the driving factor was the increasing capabilities of Soviet nuclear weapons, especially with regards to their yields. The Soviet Union had tested its first hydrogen bomb in 1953, years earlier than U.S. intelligence agencies had expected and raising concerns about the vulnerability of existing alternate command and control centers. Repeated hits in the same general area from nuclear weapons with yields in the hundreds of megatons range, or the simultaneous detonation of barrages of smaller weapons producing equivalent total yields, not to mention from potential bunker-buster designs able to penetrate dozens of feet down into the earth first, could pose a danger to hardened structures buried even hundreds of feet underground. McNamara and other proponents also pointed out that this made other above-ground strategic command and control nodes extremely vulnerable, as well.

In 1961, the U.S. military had already begun to implement the National Mission Command System (NMCS), which included two bunkers, a hardened National Military Command Center at the Pentagon and an Alternate National Military Command Center (ANMCC). The ANMCC would be an upgrade to the existing Alternate Joint Communications Center (AJCC), a facility technically part of Fort Ritchie in Maryland, but which was housed inside the Raven Rock Mountain Complex (RRMC), also referred to as Site R, across the border with Pennsylvania under the Appalachian Mountains near Blue Ridge Summit. The Department of Defense had finished building Raven Rock in 1953.

In the 1950s and the early 1960s, the U.S. government had built numerous other bunker complexes in addition to Raven Rock for continuity of government purposes, including the aforementioned Cheyenne Mountain facility, as well as the Mount Weather Emergency Operations Center in the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia. The White House and the Presidential retreat at Camp David both have underground bunkers and, until 1992, there was a bunker complex situated near the Greenbrier resort in West Virginia intended to house Congress. However, none of these were specifically associated with the NMCS infrastructure.

The NMCS wasn’t limited to hardened underground facilities, either. It also included plans for a National Emergency Airborne Command Post (NEACP) and the National Emergency Command Post Afloat (NECPA).

The first NEACP aircraft were modified KC-135B aerial refueling tankers with expanded communication suites and were in service by 1963. These aircraft, which were eventually redesignated as EC-135Js, were similar, in concept, to SAC’s EC-135A and EC-135C Looking Glass airborne command posts, which entered service around the same time. In 1962, the U.S. Navy had begun deploying smaller EC-130 Take Charge and Move Out (TACAMO) aircraft to serve as command posts to communicate with its ballistic missile submarines, in addition to land-based long-range communications sites, but these were not considered to be part of the high-level NMCS infrastructure.

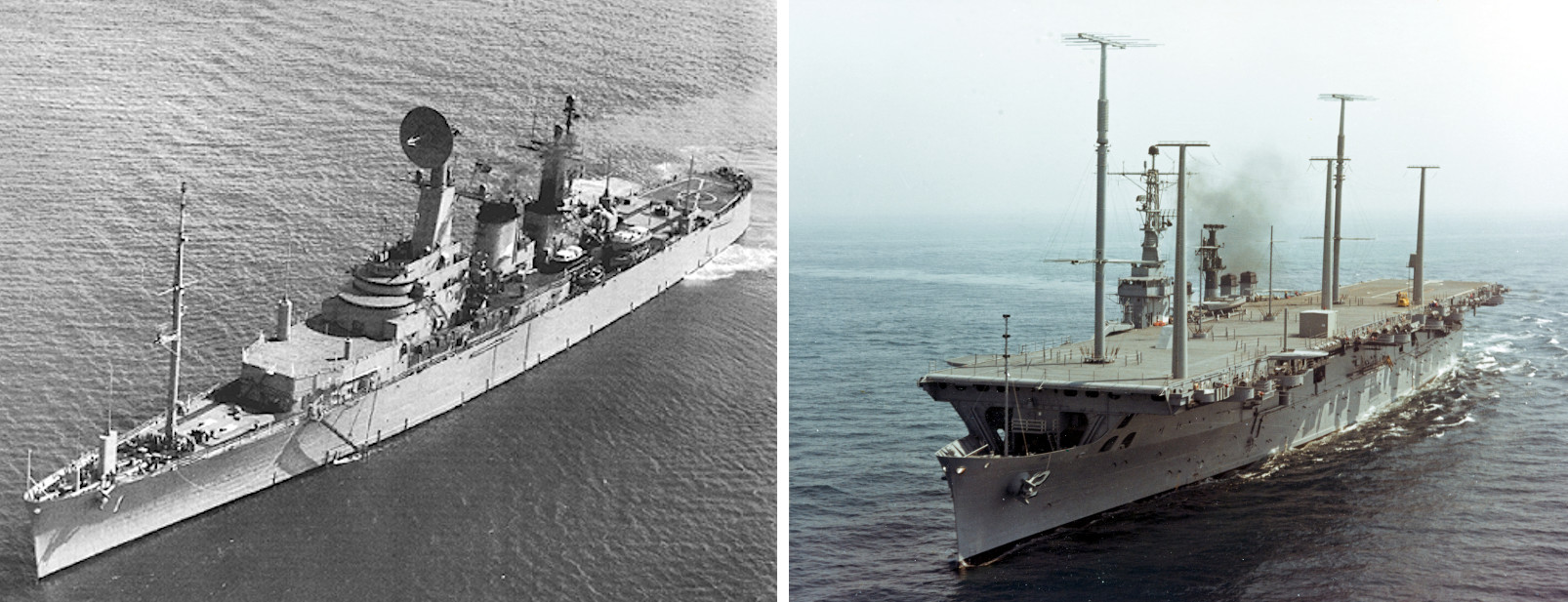

The Navy did contribute ships for the NECPA fleet. The service heavily modified the Oregon City class heavy cruiser USS Northampton and the Saipan class light aircraft carrier USS Wright to serve as strategic command ships, which entered service in 1962 and 1963, respectively. These two vessels had then-state-of-the-art communications suites and The Washington Post once described Northampton specifically as a “floating White House,” where the President and their closet advisors could operate from for protracted periods of time. You will be able to read all about these ships in an upcoming War Zone feature.

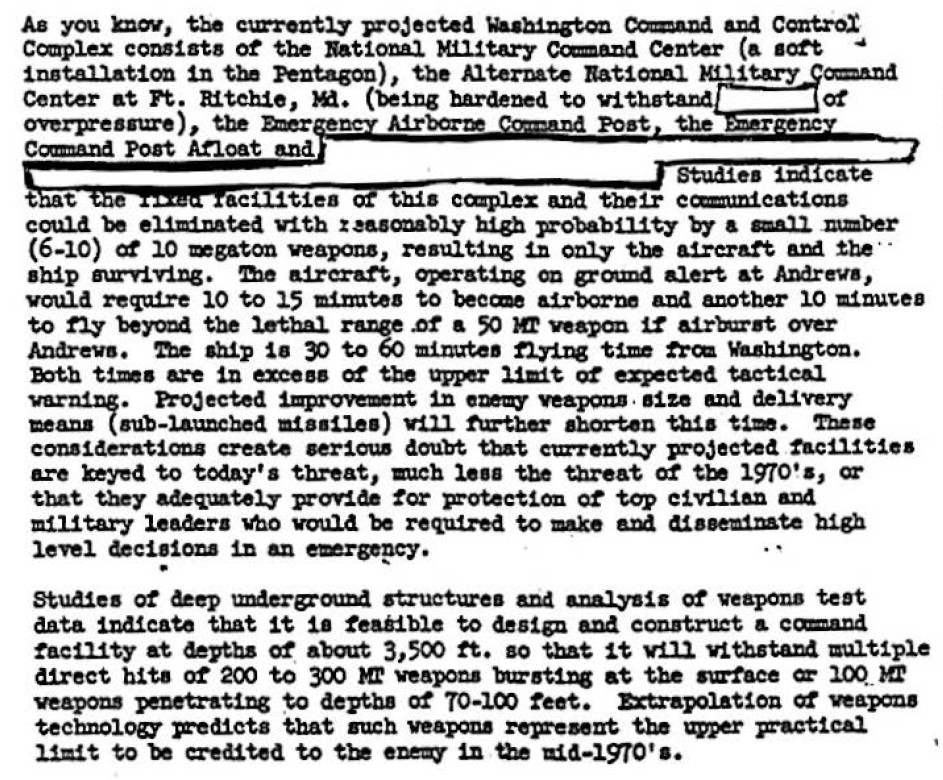

“Studies indicate that the fixed facilities of this complex [the NMCS] and their communications could be eliminated with reasonably high probability by a small number (6-10) of 10 megaton weapons, resulting in only the aircraft and the ships surviving,” according to a draft memorandum from McNamara’s office meant for then-President John F. Kennedy on Nov. 7, 1963. “The aircraft, operating on ground alert at Andrews [Air Force Base outside Washington, D.C.], would require 10 to 15 minutes to become airborne and another 10 minutes to fly beyond the lethal range of a 50 MT weapon if airburst over Andrews. The ship is 30 to 60 minutes flying time from Washington. Both times are in excess of the upper limit of expected tactical warning.”

It’s also important to remember that this memorandum came just over a year after the end of the Cuban Missile Crisis, where the United States and the Soviet Union had gotten worrying close to an actual nuclear exchange. This had served to highlight the concerns about the vulnerabilities within existing continuity of government plans that had prompted the DUCC proposal, to begin with.

In contrast to the existing and planned components of the NMSC, the DUCC concept envisioned a bunker complex situated around 3,500 feet, or two-thirds of a mile, underground. Experts had judged this to be the necessary depth to survive multiple hits from nuclear weapons in the 100 to 200 megaton range bursting on the surface or from weapons with yields up to 100 megatons capable of penetrating between 70 and 100 feet down into the ground first. SAC’s DUSC proposal had also called for a command and control center buried 3,500 feet below ground in order to withstand a 100 megaton weapon detonating on the surface anywhere within 0.5 nautical miles from the spot above ground directly above the center of the facility.

It’s worth noting that the most powerful nuclear weapon ever built, the Soviet Union’s Tsar Bomba, of which it only ever built one, had a yield of 50 megatons. However, it’s clear that senior U.S. officials, such as McNamara, feared that this weapon, which the Soviets tested in 1961, was a prelude to the widespread use of such high-yield designs.

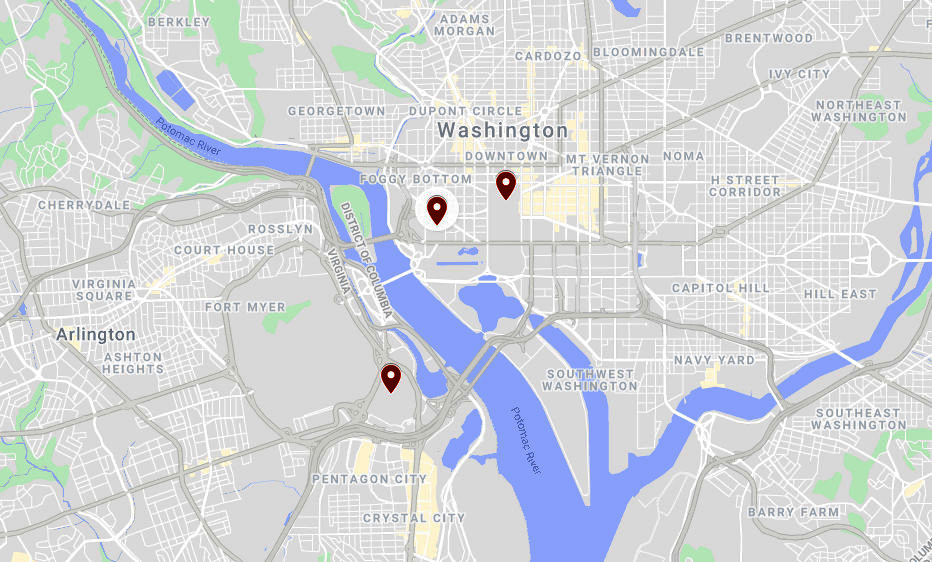

The 1963 memorandum does not say where exactly the DUCC would be located, but, plans from McNamara’s office showed it was to have been buried under the Potomac River, which lies roughly halfway between the Pentagon and the White House, according to Raven Rock: The U.S. Government’s Secret Plan To Save Itself While The Rest Of Us Die. In something out of a James Bond movie, key personnel from the Pentagon, as well as the White House and State Department, would be able to enter it by way of elevators and an underground rapid transit system.

The elevators would have discreet entrances, allowing designated individuals to make a break for the bunker undetected, straight from their offices. The elevators and transit system would allow personnel to get into the tunnel networks thousands of feet below within 10 minutes and into the actual DUCC itself within 15 minutes.

“It would have the potential of reducing significantly the problems of transition from peace to war,” McNamara wrote of the DUCC plan. “The very existence of a DUCC would also contribute in a major way to the broad objective of deterrence of enemy attack by making a survivable control posture credible and by creating the impression of a strong will to fight.”

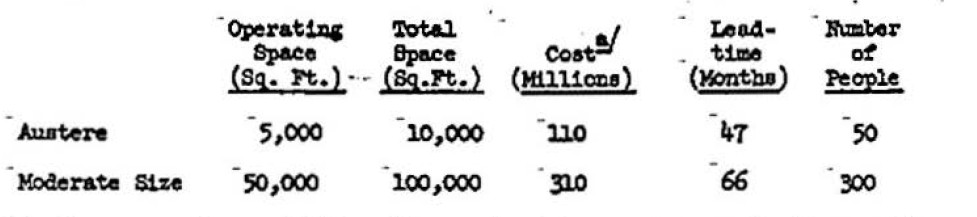

The DUCC would also be self-sufficient, with individuals inside being able to live there for at least 30 days after a massive nuclear strike. The design would be scalable, with an initial “austere size” of 10,000 square feet capable of supporting 50 individuals and the ability to expand that to “moderate” dimensions of 100,000 square feet to accommodate 300 personnel. SAC’s DUSC plan had called for a 40,000-square-foot complex capable of supporting 213 people for a similar amount of time.

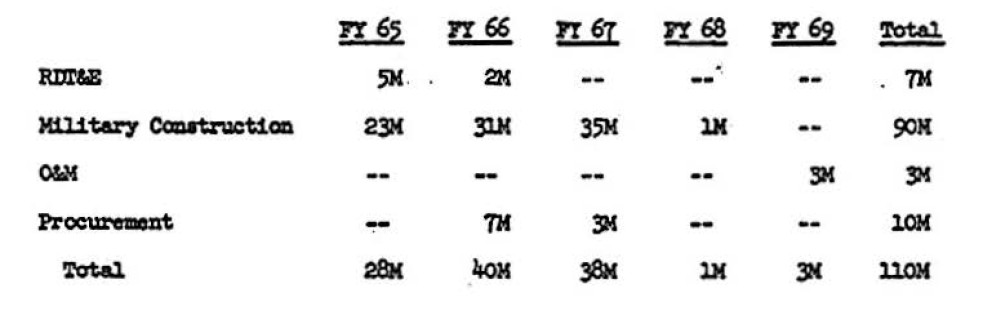

“The DUCC proposal was controversial and raised many questions, including the technical-engineering feasibility and costs, the elements of the NMCS that it might displace, and the command authorities who might be included in it (the JCS [Joint Chiefs of Staff] were among those scheduled to be included if it ever came to pass),” according to IDA’s 1975 study. In 1963, McNamara’s office had estimated that the “austere” DUCC would cost $110 million, almost $928 million in 2020 dollars, between the 1965 and 1969 Fiscal Years, almost $760 million of which would be for construction alone. The cost of the full 300-person bunker complex was pegged at $310 million, or around $2.6 billion in 2020 dollars.

Beyond that, “order-of-magnitude estimates of 5,000-10,000 psi [pounds per square inch of pressure] hardening against 100-megaton weapons, for example, were based on theoretical calculations and were received in some quarters as speculations,” IDA’s researchers noted. “Even if the basic DUCC capsule could be built to survive direct hits, questions of communications coupling and lifeline logistics remained formidable.”

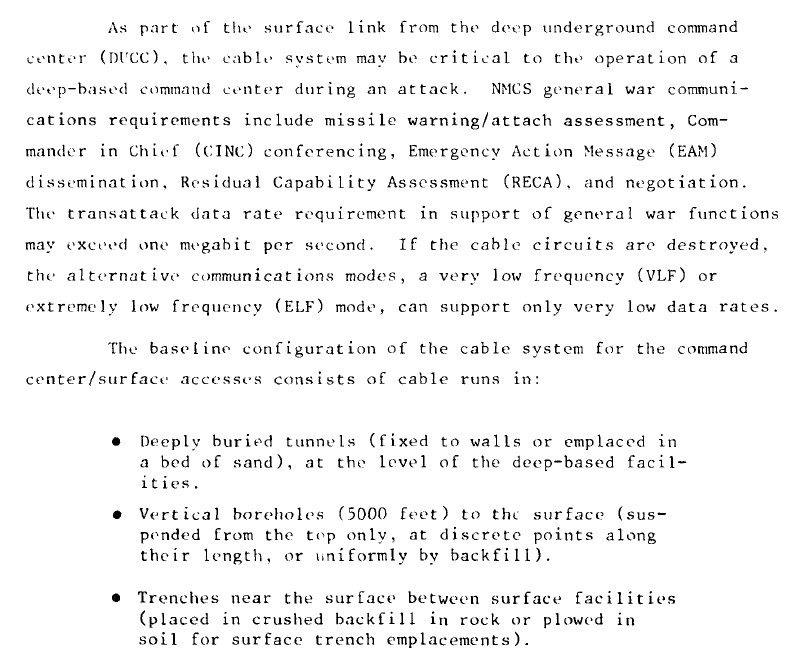

Even if the DUCC bunker itself was feasible, there were questions about whether associated communications infrastructure could ever be robust enough to ensure that it would function as intended in the aftermath of a massive Soviet nuclear strike. While the complex itself might be able to survive repeated hits from weapons with yields of hundreds of megatons, it would still need some sort of links to the outside world. Its depth would preclude direct wireless communications to other command and control nodes and force it to rely on cable networks to at least reach transmitters on the surface, or at least close to it.

Extremely low-frequency communications arrays, which you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone piece, which are themselves largely buried underground, might have provided a more hardened option, and remain in service in the United States and elsewhere for this very reason. Unfortunately, they have extremely limited bandwidth, inherently preventing them from sending any sort of complex message.

It’s not entirely clear how it happened exactly, but the DUCCs proposal did not come to fruition. Less than two weeks after the Office of the Secretary of Defense completed its final draft of the plan to send to the White House, Lee Harvey Oswald assassinated President Kennedy during a visit to Dallas, Texas. Under President Lyndon Johnson, McNamara, with support from National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy and the State Department, continued to plan for the bunker complex as part of planning for the Fiscal Year 1965 budget. However, the House Armed Services Committee refused to fund the Pentagon’s entire DUCC request for that fiscal cycle, according to the book Raven Rock. The more pressing needs of the Vietnam War were also a contributing factor.

Before the end of 1965, Johnson finally shot the entire project down, according to Spurgeon Keeny, Jr, who served as the President’s Science Adviser under Dwight Eisenhower, as well as Kennedy and Johnson. He was also a member of the National Security Council during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

Johnson’s “view of nuclear war was brought home to me by his reaction at the final meeting in 1965 on the military budget to an item listed as DUCCS. In response to his question as to what this was, he was told it stood for Deep Underground Command and Control Site, a facility that would be located several thousand feet underground, between the White House and the Pentagon, designed to survive a ground burst of a 20-megaton bomb and sustain the president and key advisers for several months until it would be safe to exit through tunnels emerging many miles outside Washington,” wrote in an article in the October 2006 edition of the Arms Control Association’s Arms Control Today magazine. “After a brief puzzled expression, Johnson let loose with a string of Johnsonian expletives making clear he thought this was the stupidest idea he had ever heard and that he had no intention of hiding in an expensive hole while the rest of Washington and probably the United States were burned to a crisp. That was the last I ever heard of DUCCS.”

Whether Keeny’s recollection was apocryphal or not, it is clear that the DUCC concept had already faced an at best lukewarm response from the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the individual U.S. military services. SAC had given up on its own DUSC bunker plans by the end of 1963 and decided to proceed with an entirely airborne emergency command and control strategy centered on its EC-135 fleets instead.

DUSC had run into its own cost problems, with estimates growing from $100 million to $200 million – just under $844 million to close to $1.7 billion in 2020 dollars – and the estimated date for when SAC could begin using the facility got pushed back from 1965 to 1969. “Economic considerations favored a construction site in a deep mine near Cripple Creek, Colo., but SAC found the location too remote from its main headquarters and operationally disadvantageous for continuity,” according to IDA’s 1975 review. The use of an abandoned mine shaft in the plan has since evoked references to the “mineshaft gap” scene from the famous Cold War dark comedy Dr. Strangelove, which came out in 1964.

Still, without something like DUCC, concerns about the vulnerability of U.S. strategic command and control facilities persisted. There were proposals to use anti-ballistic missile systems to help guard existing command and control infrastructure.

“Throughout the years prior to 1968, the option of seeking to protect national authorities and the NMCS by means of an active ABM defense system remained a hypothetical possibility,” according to IDA’s 1975 study. “Both the Nike-Zeus system of the late 1950s and the Nike-X system of the 1960s had been perennial JCS recommendations for deployment as active defense systems, justified primarily in terms of what McNamara called ‘damage limitation,’ i.e., protection of US population and industry. Protection of government and military command and control centers, when it was mentioned at all, was put forward as a distinctly secondary and presumably not decisive mission.”

“It was not until the Safeguard program was advanced by the Nixon administration, based on active ABM defense of strategic offensive forces, that protection of command and control was made a high priority mission for ABM defense,” the report continued. Safeguard, which began in 1969, was aimed at providing a defensive shield for the Air Force’s Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) fields.

The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, which President Richard Nixon and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev signed in 1972, severely curtailed strategic ABM system deployment by both countries. It marked the beginning of the end for Safeguard, which ceased operations in 1976, less than a year after it had first entered service.

The NMCS had begun to go through its own changes in the 1970s, as well. In 1970, the Navy decommissioned both USS Northampton and USS Wright, bringing the NECPA mission to an end. In the early 1970s, the Air Force began the process of replacing the three EC-135J National Emergency Airborne Command Post aircraft with three more capable Boeing 747-based E-4A Advanced Airborne Command Post planes.

With all this in mind, the topic of a new DUCC project came up against at least once in the late 1970s as part of a report from the Defense Communications Agency on requirements for the Worldwide Military Command and Control System (WWMCCS) in the post-1985 timeframe. “A deeply buried command and control center for the National Military Command System (NMCS) is an attractive option, based on an evaluation of performance, survivability, and cost,” a 1978 separate report from the Defense Nuclear Agency explained, citing the WWMCCS study.

The Defense Nuclear Agency’s report had to do with testing of various types of structures, including tunnels and boreholes for armored communications cables, under laboratory conditions ahead an underground test of a W87 warhead, known as shot Diablo Hawk, which was part of Operation Cresset. Diablo Hawk’s primary goal was to observe the effects of the W87, with its yield of approximately 300 kilotons, in a tunnel, which also offered a good opportunity to test the effects of a large nuclear explosion on structural features that would be found on a deeply buried hardened facility. The W87 was the warhead employed on the LGM-118A Peacemaker ICBM, before its retirement, and remains in use on the LGM-30G Minuteman III.

While testing around Diablo Hawk provided valuable data for a new DUCC project, there is no indication that the U.S. military ever pursued building one. The improving accuracy of Soviet, and now Russian, nuclear-armed missiles has only made the idea of developing a bunker able to withstand repeated hits during a nuclear exchange more difficult, if not impossible.

The vast majority of what is known about the U.S. military’s strategic command and control infrastructure remains largely unchanged in its basic principles from how it operated in the 1960s. With the exception of the Greenbrier resort, all of the other bunker complexes mentioned in this story remain active. Raven Rock and Cheyenne Mountain have also received notable upgrades to their capabilities over the years. There are a number of other hardened facilities available to support continuity of government operations, as well, spread out on the East Coast of the United States.

In addition, airborne command and control centers remain at the core of how the National Command Authority would communicate with the elements of the U.S. nuclear triad during a major crisis. In the 1980s, the E-4As were upgraded into E-4B National Airborne Operations Centers and a fourth plane was added to the fleet. All four of these aircraft remain in service today. In the late 1980s, the E-6A Hermes, later renamed the E-6A Mercury, also took over the TACAMO role from the Navy’s previous EC-130-based platforms. In the 1990s, the Mercury fleet was upgraded into the E-6B configuration and supplanted the Air Force’s EC-135 Looking Glass aircraft, as well. The Air Force is now working on acquiring a replacement for the E-4Bs, which could also supplant other airborne command post and VVIP aircraft, such as the E-6Bs and C-32A Air Force Twos, respectively.

Still, even though the idea of building a super-hardened DUCC remains as ambitious today as it did in the 1960s, it’s fascinating to think about how the United States almost built what might have been the best-protected underground base more than a half a mile underneath the Washington, D.C. area.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com