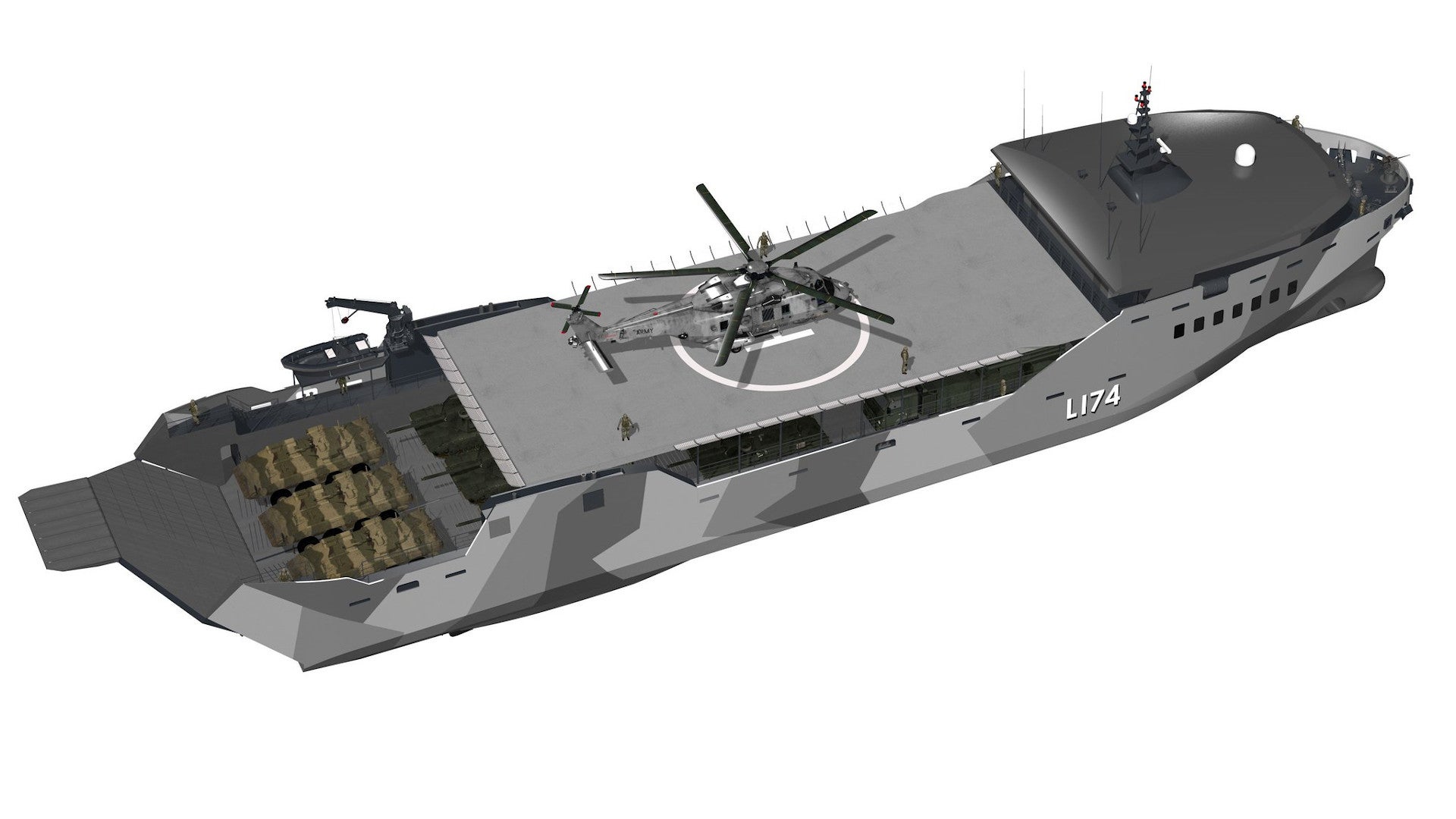

The U.S. Navy wants to buy as many as 30 of a new class of Light Amphibious Warships that would be significantly smaller and cheaper to operate than its existing fleets of large amphibious ships. The service is already exploring possible designs, including a roll-on-roll-off type with a stern ramp. These vessels will be a critical component of how it supports the U.S. Marine Corps’ new and still evolving plans for how it will conduct future expeditionary and distributed operations.

Navy officials from PMS 317 said that the “objective number” of Light Amphibious Warships (LAW) it hopes to buy is between 28 and 30 at a briefing for defense industry representatives on Apr. 9, 2020. Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) posted the briefing slides, as well as responses to questions, on the U.S. government’s contracting website beta.SAM.gov on May 5.

PMS 317 is the program office within NAVSEA’s overarching Program Executive Office for Ships that is presently responsible for the San Antonio class landing platform dock program, as well as a program to acquire a replacement for the Whidbey Island and Harpers Ferry classes of landing ship docks.

“Evolving threats in the global maritime environment causing the Naval Forces to re-evaluate/adjust their CONOPs [concepts of operation] to meet the new challenges associated with maintaining persistent Naval forward presence to enable sea control and denial operations,” is how PMS 317 described the underlying need for the new class of amphibious ships at the April briefing. The LAW is “intended to provide Naval Forces the maneuver and sustainment vessels to confront the changing character of warfare.”

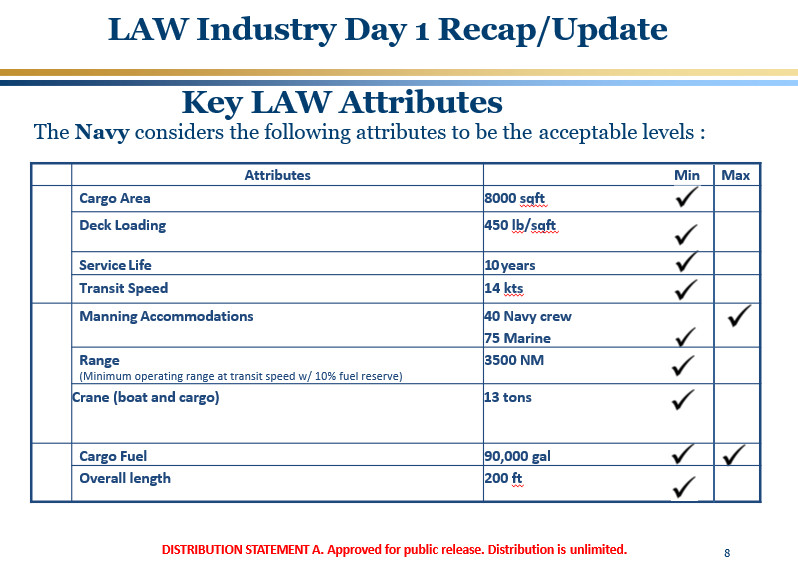

The Navy is still in an information-gathering phase, but does already have some key requirements for any potential LAW design, which it expects to be about 200 feet long overall and have 8,000 square feet of cargo space in total. Each LAW will have a crew of no more than 40 sailors and be able to accommodate at least 75 Marines.

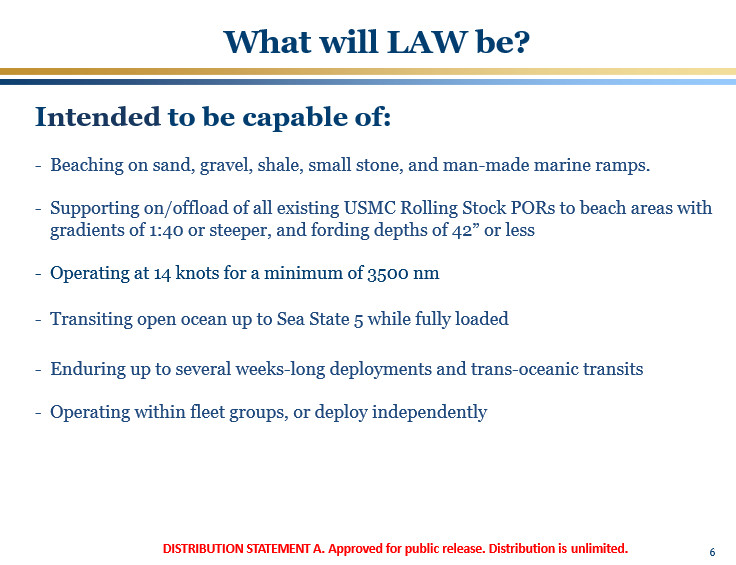

The ship has to be capable of “beaching on sand, gravel, shale, small stone, and man-made marine ramps” just like a traditional landing craft or larger landing ship. It has to be able to deploy all Marine Corps vehicles and other “rolling stock,” such as towed howitzers and equipment trailers, onto a beach with at least a two-and-a-half percent gradient, if not more, or into a situation where the vehicles would have to ford at depths of 42 inches or less.

The LAWs also need to be capable of open-ocean operation in conditions up to Sea State 5, defined as “rough seas” with waves between eight and 13 feet high. The Navy wants the ships to be able to cruise at 14 knots and have a maximum range of 3,500 nautical miles. The vessels will need sufficient accommodations and amenities to support weeks-long, trans-oceanic voyages.

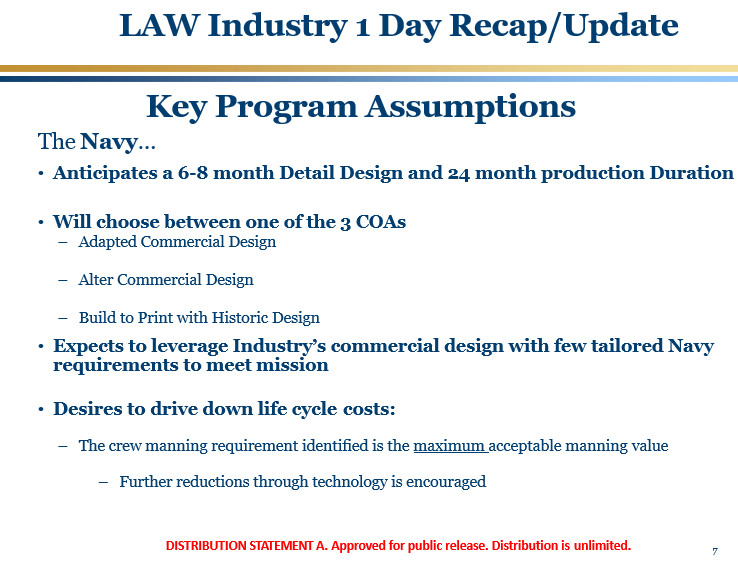

The Navy says that it is willing to consider either adapting an existing commercial design, using a commercial hullform as a starting place, or a so-called “Build to Print” ship based on proven design elements and components. The goal in all of these courses of action is to focus on relatively low-risk, low-cost, mature designs, or at least design features, in order to both keep the ships cheap and make them faster and easier to build. The Navy has said it is interested in awarding at least one preliminary design contract by the end of this year with the hope that it could begin buying actual ships as early as late 2022.

The service has also indicated that it might be willing to accept ship designs with relatively short expected service lives in order to help keep production costs low and speed up construction. The requirements now say that the LAWs have to have a life span of just 10 years, at a minimum.

Exactly what the LAWs might look like remains to be seen. Last year, the Navy and Marines said that they were examining offshore support vessel (OSV) type ships as one possible option. The Navy has facilitated the development and delivery of OSVs to Iraq in the past and has employed modified commercial examples to support various experiments, including those related to work on unmanned surface vessels. However, these ships are not intended to safely beach themselves and do not necessarily have a ramp or other means of rapidly on-loading and off-loading vehicles, personnel, and other equipment at established port facilities.

“He doesn’t call it an OSV, but he does say small, scalable, more maneuverable, flexible kinds of things,” Frank DiGiovanni, the Deputy Director of Expeditionary Warfare on the Chief of Naval Operations’ staff, told USNI News in February, referring to Marine Corps Commandant General David Berger’s calls for new, lighter amphibious ships in his planning guidance last year and other occasions since then. “The OSV is certainly a class or a type of ship we’ve worked with before.”

Berger’s 2019 planning guidance, together with a concept called Force Structure 2030 that emerged publicly in March, describes ambitious plans to radically reshape the Marines for new kinds of expeditionary and distributed warfare operations, especially in the Pacific region. You can read more in detail about both of these new sets of guiding policies in these past War Zone pieces.

The commandant’s plans focus heavily on being able rapidly deploy Marines to a specific area, such as one island in a chain, establish an outpost, conduct operations, and then quickly move those forces to a different location in the same general operating area. The idea is that this upends an opponent’s response planning, reducing the vulnerability of the Marines to counter-attack, while also forcing an enemy to stretch their own assets across a wide area to try and defend against threats from constantly changing vectors. Small amphibious ships are essential for both moving these elements around and keeping them resupplied.

USNI News

has since reported that the discussion between the Navy and the Marines regarding the new amphibious ship has now shifted to so-called stern landing vessels and one design, in particular, from the Australian firm Sea Transport Solutions (STS), to serve at least as a conceptual starting place. STS was notably not among the companies present at the April 2020 industry day gathering regarding the LAW.

The U.K.’s Royal Navy is also investigating a larger type of adapted commercial vessel with a stern ramp to serve as a Littoral Strike Ship to support its own plans to transform the structure of the Royal Marines. The vessel that the British say they are considering is at least visually quite similar to the M/V Ocean Trader, a shadowy U.S. special operations mothership, which the Navy nominally operates and that the War Zone has covered extensively in recent years.

What the Navy has outlined in its basic requirements for the LAW also sounds very similar in many respects to the Army’s General Frank S. Besson class Logistics Support Vessels (LSV), the largest types of ships in that service’s obscure, but significant watercraft fleets, which you can read about in more detail in this previous War Zone story.

The last two members of the Besson class actually form a distinct subclass and are designed to be much more capable of long-range, open-ocean operations. All of the LSVs can beach or can use their front and rear ramps to take on and unload cargo in more established ports.

At the April 9 briefing, in response to a question, the Navy said it had not reached out to the Army about what the service was doing as part of its Maneuver Support Vessel (MSV) program. In 2017, that service awarded the first contract for its new MSV (Light) landing craft, meant to replace its Vietnam War-era Landing Craft Mechanized Mk 8s.

However, the Army had, at least in the past, been looking at larger vessels to replace both its Landing Craft Utilities (LCU) and LSVs as part of a larger MSV effort. At the same time, the service had been planning to retire the bulk of its watercraft fleets last year, before pressure for Congress prompted them to halt those plans.

“Yes, we are aware of it and the capabilities. They may look similar, but the requirements are fundamentally different,” Navy officials said of the Army’s vessels, though it is not entirely clear which types they were talking about specifically. “[The] Navy needs more habitability, seakeeping, and intra‐theater focus for LAW.”

The LAW requirements, such as they are known now, are also reminiscent in some respects to old Landing Ship Tanks (LST), which the Navy made heavy use of during World War II and that also saw significant service during the Korean War and Vietnam War. Those ships were notably larger than what the service is talking about buying now, though.

In the late 1960s, the Navy also acquired a number of even bigger Newport class LSTs, which served into the 1990s. Still, the LAW definitely represents a blast from the past with regards to lighter amphibious capabilities that the service had largely moved away from decades ago.

With the Navy looking to get the Light Amphibious Warship’s design phase underway as early as the end of this year, its requirements, as well as what shipbuilders are able to offer, are likely to become clearer in the coming months. It will be interesting and exciting to see what gets proposed for what could be one of the service’s most significant acquisitions of new amphibious ships in recent memory as it works to support the Marine Corps’ future operational ambitions.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com