U.S. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper has revealed new details about extremely ambitious plans to increase the size of the U.S. Navy’s fleets to more than 500 ships and submarines, including unmanned types, within the next 25 years. He also offered some specifics about how the Pentagon hopes to pay for this dramatic increase in force structure, including a significant increase in the Navy’s base budget starting as early as the next Fiscal Year.

Esper provided the new information on what is now being called Battle Force 2045 in a virtual talk he gave from the offices of the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) think tank in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 6, 2020. Some details about the Navy’s future force structure and shipbuilding plans had already emerged in September, which you can read about in more detail in this recent War Zone piece.

The Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) has been working for months to help shape the plans for the Navy’s force structure in the decades to come. OSD’s Battle Force 2045 proposal incorporates recommendations from studies that the Pentagon’s Office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE), the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Hudson Institute think tank conducted. A full look at the plan is expected to be publicly released next Spring as part of the formal 2022 Fiscal Year defense budget request.

As of early 2020, the Navy had around 293 ships. There is also a Congressionally mandated goal of a fleet with at least 355 ships. However, Esper has now said that the Battle Force 2045 structure will call for a total naval force with more than 500 ships, including between eight and 11 nuclear-powered aircraft carriers, 60 to 70 small surface combatants, 70 and 80 attack submarines, 50 to 60 amphibious warfare ships, and 70 to 90 logistics ships. This is broadly in line with draft proposals from CAPE and the Hudson Institute.

Both of those studies described a Navy with nine aircraft carriers. The force structures CAPE and Hudson included 70 and 56 small surface combatants, respectively, and both called for an increase in the size of the service’s submarine force, which presently has 55 boats, in total. Those proposals also called for between 15 and 19 traditional amphibious warfare ships, such as amphibious assault ships and dock landing ships, and 20 to 26 of a new class of Light Amphibious Warships (LAW) that the Navy and Marine Corps are already exploring. These studies included significant increases in logistics and other support vessels, as well.

The carrier figures are particularly interesting given that the Navy has 11 flattops right now – the 10 Nimitz class ships and the first-in-class USS Gerald R. Ford – and anything less would represent a cut in the total number of these vessels. Congress has also stipulated that the service always be working toward having at least 12 operational carriers.

Esper added that the Navy would “continue to examine options for light carriers that support short-takeoff or vertical landing aircraft” and that the service could ultimately aquire up to six such ships, which could be based on the aviation-focused America class amphibious assault ship design. This is notable given that the Navy had publicly said that it had deferred a study of light carrier concepts indefinitely in May. This could also simply involve using the existing Americas, as well as other amphibious assault ships, as small “Lightning Carriers” with larger than average compliments of U.S. Marine Corps F-35B Joint Strike Fighters, a concept the Navy and Marines have already been exploring.

The Secretary of Defense did not offer details about what might be included in the “small surface combatant” category, but presently the Navy’s only ships meeting this description are the Freedom and Independence classes of Littoral Combat Ships (LCS). The service is working to acquire a new class of guided-missile frigates, presently referred to as FFG(X), which will be based on from Italian shipbuilder Fincantieri’s European Multi-Purpose Frigate design, also commonly referred to simply by the Franco-Italian acronym FREMM.

When it comes to submarines, Esper said that the increase in the total number of boats will come from extending the life of seven Los Angeles class attack submarines by refueling their nuclear reactors, as well as the development of a new type of advanced attack submarine, known presently as the SSN(X). The Navy has said that it is looking to acquiring something akin to the advanced Seawolf class design under this latter program.

In addition, the Secretary of Defense reiterated the service’s previously established goal of increasing production of the more multi-mission-focused Virginia class attack submarine from two boats per year to three. “If we do nothing else, the Navy must begin building three Virginia class submarines a year as soon as possible,” Esper said.

These increases in traditional vessels offer a “credible path” to the 355 ship goal, according to Esper. However, to get the total size of the Battle Force up to over 500 will require the inclusion of between 140 and 240 unmanned surface and undersea vehicles in that total, something the Navy does not presently do. The growing importance of unmanned platforms to the service’s future plans, which you can read about in these previous War Zone pieces, has already prompted calls from the White House’s Office of Management and Budget to add them to the official fleet totals for both current accounting and future planning purposes.

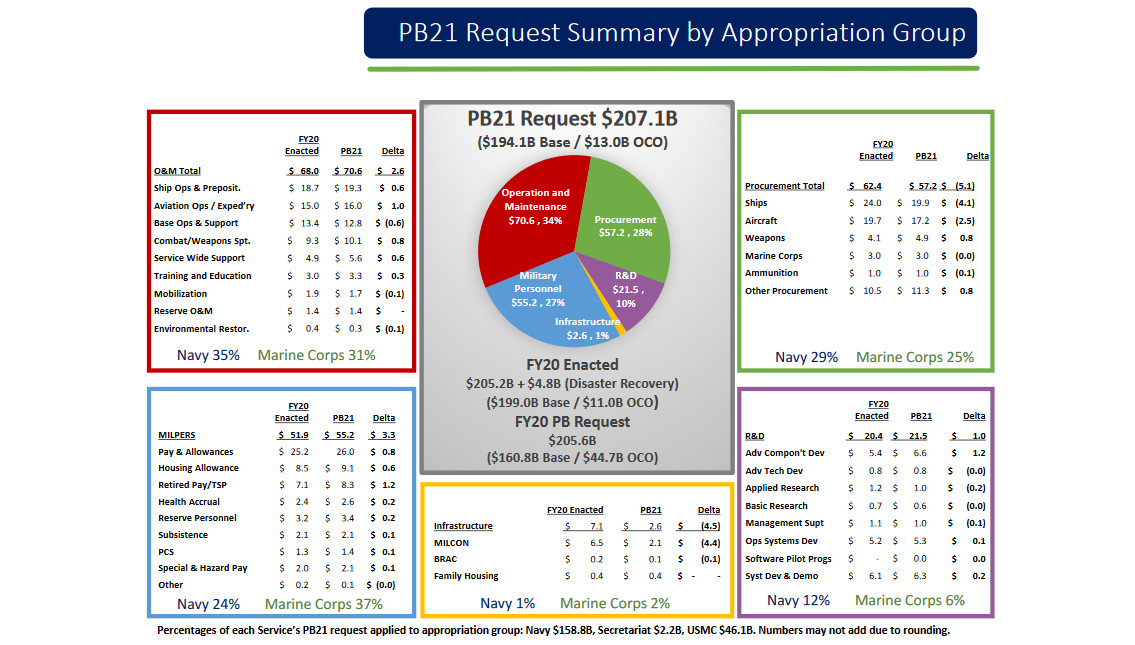

To make all this work, Esper said that the plan is to increase the percentage of the Navy’s overall budget set aside for shipbuilding to 13 percent. In the 2020 Fiscal Year, the money for ships accounted for just over 11.5 percent of the service’s approved budget from Congress. This dropped to less than 10 percent in the Navy’s 2021 Fiscal Year budget request. Legislators have yet to pass a budget for this fiscal cycle, which began on Oct. 1.

This 13 percent figure had first emerged last month in a print version of a speech Esper gave at the Rand think tank. However, the actual speech did not include this figure, raising questions about whether or not it was accurate. As Defense News

reported at the time, even a two percent increase in shipbuilding funds over the 2021 Fiscal Year budget request would translate to more than $4 billion extra dollars to buy more ships.

In his latest remarks on this topic from CSBA’s offices, Esper also called on Congress to approve getting rid of older ships and to grant the Pentagon authority to transfer unused funds straight to shipbuilding accounts without the need for specific authorization. He also issued an appeal to legislators to pass the 2021 Fiscal Year budget without delay and avoid relying on short-term spending bills, commonly known as Continuing Resolutions, which make long-term planning difficult.

As was the case after the initial details about the Navy’s future plans for a fleet of more than 500 ships first emerged, it remains very much to be seen whether this proposal will become a reality. Congress has been notably reticent to the idea of including unmanned platforms in the Battle Force totals, or even just building them at all, and routinely resists proposals to retire existing warships, or otherwise trim back their expected service life, to free up funds to buy newer ones. With this in mind, extending the life of existing warships had been part of the Navy’s plans to reach the existing 355-ship goal as recently as last year.

Available shipyard capacity to build new ships and submarines, as well as maintain a growing fleet, remains very much an issue, as well. The shift from building one Virginia class submarine each year to two notably caused strain on the yards where those boats are built, at least initially, raising questions about what might happen when production increases to three annually. Those are also the same yards that will also be needed to construct the Navy’s future Columbia class ballistic missile submarines.

If nothing else, there is also a basic cost question. Esper indicated that at least some of the increased shipbuilding funds could come from savings the Pentagon has found elsewhere in the budget, but again canceling or scaling back other projects or retiring older weapon systems across the U.S. military will require the consent of Congress.

In addition, there’s no guarantee, especially in the midst of a major recession in the United States and global economic downturn due to the COVID-19 pandemic, that defense spending will continue to rise in a way that will support a major increase in the size of the Navy’s Battle Force. In fact, there’s evidence already that it could well be headed in the opposite direction.

Sustaining such a naval force will require major additional funding, as well. One estimate from the Congressional Budget Office regarding a plan the Navy released last year to reach a 355-ship fleet pegged the annual cost of just operating and maintaining all of those vessels at $40 billion. For context, the Navy’s total “O&M” budget for the 2020 Fiscal Year was $68 billion and the portion set aside specifically for ship operations was $19.7 billion.

All told, the Office of the Secretary of Defense and the Navy seem to be intent on setting a goal of having a total fleet with more than 500 ships in the coming decades. However, from everything we know so far, there are serious hurdles they will need to overcome first in getting anywhere near to realizing their vision.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com