After months of investigating the circumstances relating to two separate collisions between the Arleigh Burke-class destroyers USS Fitzgerald and USS John S. McCain and merchant ships in the Pacific Ocean, the U.S. Navy has determined both incidents were “preventable” and “avoidable,” blaming numerous officers and sailors for the incidents, which left a total of 17 Americans dead. The nature of accidents had initially seemed so bizarre that they quickly prompted a raft of conspiracy theories, but the official investigations reinforced subsequent reports that pointed instead to almost recklessly poor training and readiness standards and dangerously low morale.

In an associated press release, the Navy described the mishap involving Fitzgerald and the container ship M/V ACX Crystal on June 17, 2017 as the result of “an accumulation of smaller errors over time, ultimately resulting in a lack of adherence to sound navigational practices.” When the John McCain collided with the chemical tanker M/V Alnic MC on Aug. 21, 2017, “complacency, over-confidence, and lack of procedural compliance,” were major factors in the accident.

A wide-spread issue

Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson, the Navy’s top officer, issued the following statement to coincide with the release of the report:

“Both of these accidents were preventable and the respective investigations found multiple failures by watch standers that contributed to the incidents. We must do better.

“We are a Navy that learns from mistakes and the Navy is firmly committed to doing everything possible to prevent an accident like this from happening again. We must never allow an accident like this to take the lives of such magnificent young Sailors and inflict such painful grief on their families and the nation.

“The vast majority of our Sailors are conducting their missions effectively and professionally – protecting America from attack, promoting our interests and prosperity, and advocating for the rules that govern the vast commons from the sea floor to space and in cyberspace. This is what America expects and deserves from its Navy.

“Our culture, from the most junior sailor to the most senior Commander, must value achieving and maintaining high operational and warfighting standards of performance and these standards must be embedded in our equipment, individuals, teams and fleets.

“We will spend every effort needed to correct these problems and be stronger than before.”

The public reports can only contain unclassified information about the Navy’s protocols and standard operating procedures and the equipment and capabilities of the two Arleigh Burke-class destroyers. The reviews also make clear that the Navy has no reason to suspect there is any weight to any conspiracy theories, such as those involving sabotage, cyber attacks, or other interference by foreign countries.

The Navy made no determination about whether the civilian crews onboard the merchant vessels may ultimately bear some responsibility, as well, details that will likely come out in additional U.S. and Japanese Coast Guard investigations. That being said, they still describe a near total breakdown in leadership and almost deliberately poor decision making on the part of the service’s own crews.

What happened aboard Fitzgerald

In the case of the Fitzgerald, the ship was within sight of land and was running with only external navigation lights on when it came into contact with the ACX Crystal, a common procedure. Per the official International Rules of the Nautical Road, the American destroyer was in a so-called “crossing situation” and should have moved out of the path of the other vessel. When that didn’t happen, the container ship’s crew was supposed to do the same.

Though aware of the situation for 30 minutes before the collision, neither ship took evasive action leading up to the mishap. Minutes before the two smacked into each other, Fitzgerald’s Officer of the Deck and Junior Officer of the Deck, the former in charge of the ship’s safe navigation and the other there to assist, were still debating on the bridge whether or not change course.

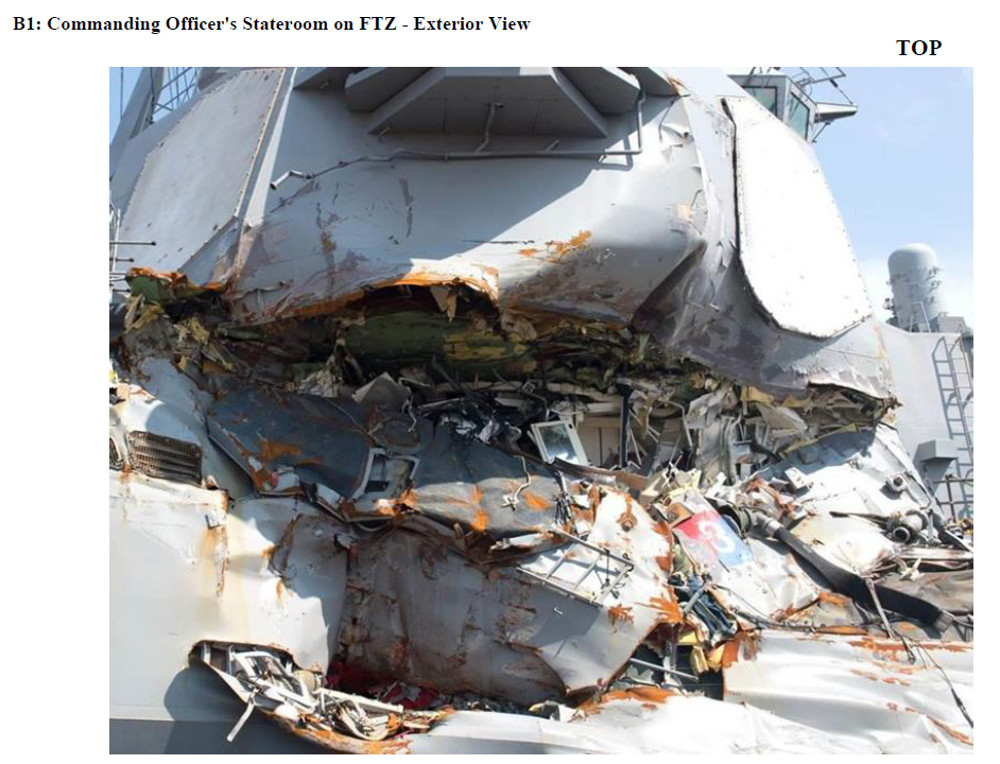

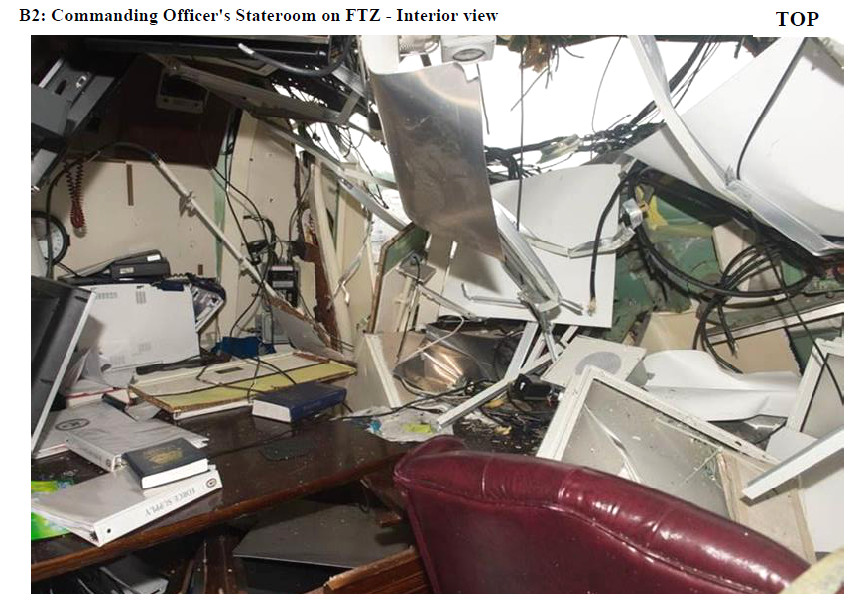

At no point did any other personnel on the bridge appear to offer substantive advice, according to the review, and the ship’s captain, who was asleep at the time, was completely unaware of what was going on, a breach of protocol, until the ACX Crystal literally smashed its way into his quarters. The destroyer’s Combat Information Center, which fuses data from the ship’s radar and other sensors, never offered information or advice to the Office of the Deck.

At no point did personnel on the bridge sound a collision warning or otherwise alert the rest of the crew, many of whom were also in their bunks, of the impending danger. The accident caused such significant damage as to knock out the Fitzgerald’s external communications systems, preventing the crew from quickly calling for help, and all power to the forward spaces of the ship.

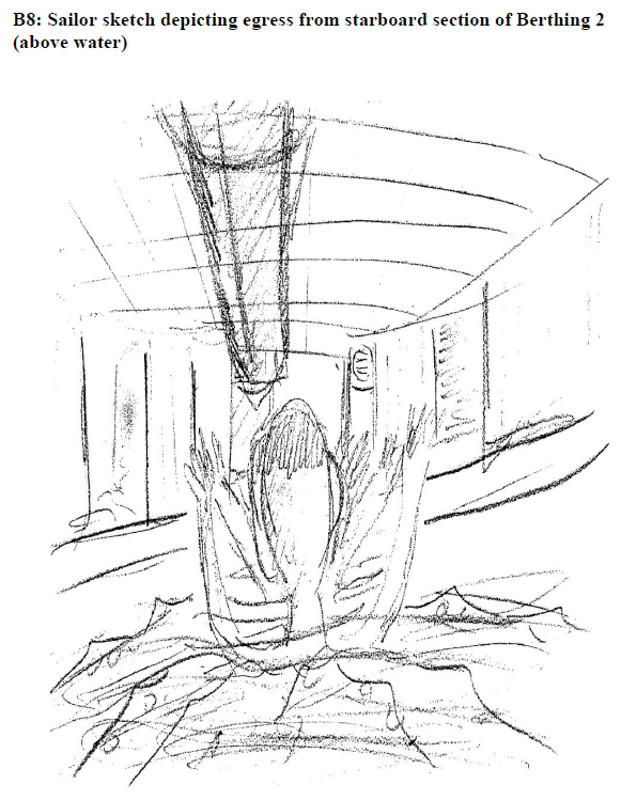

As we at The War Zone reported before, based on an initial release of information to the public, that the incident wasn’t worse is a testament to the courage of the ship’s crew in the immediate aftermath. Along with these latest reports, the Navy released a number of haunting hand drawn sketches investigators had sailors draw of how they escaped the flooding in the compartments.

This description of how sailors rescued the captain from his cabin is particularly harrowing:

“Five Sailors used a sledgehammer, kettlebell, and their bodies to break through the door into the CO’s cabin, remove the hinges, and then pry the door open enough to squeeze through. Even after the door was open, there was a large amount of debris and furniture against the door, preventing anyone from entering or exiting easily.

“A junior officer and two chief petty officers removed debris from in front of the door and crawled into the cabin. The skin of the ship and outer bulkhead were gone and the night sky could be seen through the hanging wires and ripped steel. The rescue team tied themselves together with a belt in order to create a makeshift harness as they retrieved the CO, who was hanging from the side of the ship.”

But the Navy found a laundry list of failures just in the moments leading up to the crash. The Officer of the Deck and the rest of the team on the bridge were apparently largely unfamiliar with the International Rules of the Nautical Road, failed to take responsible action to get the destroyer out of the way in the first place, didn’t notify other vessels in the area of a possible hazard, and kept the ship going at an unsafe speed given the other ships in the congested shipping lanes.

The watch team didn’t position the ship’s radar and other personnel did not appear to use civilian Automated Identification System transponder beacon information to provide the personnel on the bridge with the best picture of the situation possible and weren’t even physically watching what was going on to the right of Fitzgerald where the ACX Crystal and two other ships were sailing.

A near complete failure of leadership and communication before and leading up to the mishap meant that key individuals were not working together as a team for some time before hand. The Navy said that the destroyer had another near collision in May 2017, but that the ship’s command team “made no effort to determine the root causes and take corrective actions in order to improve the ship’s performance.”

Oh, and beyond all that, the ship’s crew was just dangerously fatigued. The strain on the Navy to meet operational demands, often operating ships with inadequate or overworked crews, is something that has since emerged as a broad, service-wide issue in need of fixing, which you can read more about in depth here.

“No single person bears full responsibility for this incident,” the Navy investigators concluded. “The crew was unprepared for the situation in which they found themselves through a lack of preparation, ineffective command and control, and deficiencies in training and preparations for navigation.”

The McCain collision

When McCain collided with the Alnic MC nearly two months later, the circumstances were in many ways even worse. Both the ship’s captain and executive officer were on the bridge due to the “higher risk” nature of sailing in heavily trafficked Singapore Strait and Strait of Malacca. As with Fitzgerald, the destroyer was following the common procedure of sailing with just its navigation lights on even though there was near total darkness. It is possible that if the crew had responded appropriately to a possible dangerous situation that they would have turned on floodlights and other equipment to make sure other ships in the area were better aware of the destroyers presence and exact position.

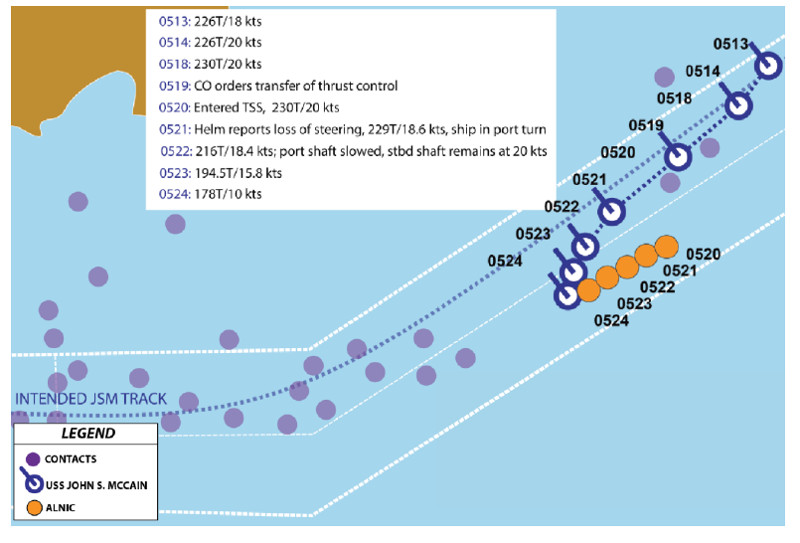

As the American warship entered the shipping lanes, it became apparent that the helmsman, in charge of steering the ship, was having trouble properly adjusting the vessel’s speed, while also keeping it on course. The commanding officer ordered another individual to assist, which involved that individual actually taking over some of the controls through their own console.

Unfortunately, the move confused everyone. Instead of just shifting the speed controls to the other workstation, the steering functions got redirected, too. The Helmsman had no idea this was the case and thought they had completely lost control of the ship.

Though this wasn’t actually the case, at that moment no one was guiding the ship. At the same time, the movement of the computerized controls between workstations placed the ship’s rudder back in the default, centered position, from where it had been, one to four degrees to the right. This caused the ship to immediately begin drifting to the left.

Standard Navy protocol says a ship should immediately slow down when it suffers a “steering casualty,” as well. The assisting Helmsman, known as the Lee Helmsman, had misunderstood the controls, though, and only slowed one of the destroyer’s two screws, leaving the other running at the previous speed for more than a minute, exacerbating the leftward movement and shunting the McCain further into the path of other ships.

In the three minutes it took for someone to finally realize that the ship’s steering was fine, it was too late to avoid the impact with the Alnic MC. As with the Fitzgerald’s mishap, neither of the ships attempted to contact the other and the McCain never sounded a collision warning, even when it should have been obvious that an accident was inevitable.

External communications failed afterwards and the impact seriously degraded the ship’s navigation equipment and caused a loss of electric power in many compartments. “Those nearest the impact point described it as like an explosion,” the official report noted.

As with the earlier collision, the McCain’s crew did heroically work to prevent the incident from being any worse. The Navy’s new report reveals additional harrowing stories about this accident, as well, such as the following:

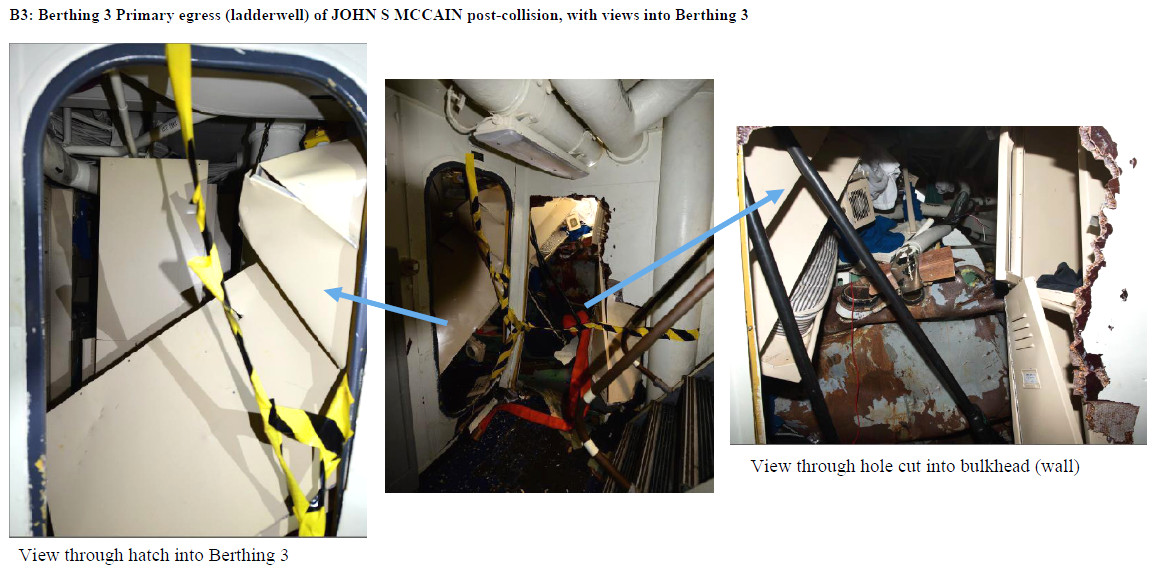

“The second Sailor was in a bottom rack in Berthing 3. His rack was lifted off the floor as a result of the collision, which likely prevented him from drowning in the rising water, and he was trapped at an angle between racks that had been pressed together. Light was visible through a hole in his rack and he could hear the water and smell the fuel beginning to fill Berthing 3.

“He attempted to push his way out of the rack, but every time he moved the space between the racks grew smaller and he was unable to escape. His foot was outside the rack and he could feel water. It was hot in the space and difficult to breathe, but he managed to shout for help and banged against the metal rack to get the attention of other Sailors in the berthing space. The Sailors who entered Berthing 3 to rescue others heard this and began assisting him, but he was pinned by more debris than the first Sailor freed.

“It took approximately an hour from the time of the collision to free the second Sailor from his rack. Rescuers used an axe to cut through the debris, a crow bar to pull the lockers apart piece by piece, and rigged a pulley to move a heavy locker in order to reach the Sailor. Throughout the long process, his rescuers assured him by touching his foot, which was still visible. Once freed, the Sailor was the last person to escape Berthing 3. Everything aft of his rack was a mass of twisted metal. He had scrapes and bruises all over his body, suffered a broken arm, and had hit his head. He was unsure whether he remained conscious throughout the rescue.”

In its investigation, the Navy found that the McCain’s Helmsman, Lee Helmsman, and other personnel lacked of adequate training on the steering and speed controls. On top of that, several sailors on the bridge during the accident had been earlier temporarily assigned similar duties on board the USS Antietam, a Ticonderoga-class cruiser with a significantly different control layout, which led to apparent confusions and a lack of understanding of what was going on when it appears the steering had given out.

“Multiple bridge watchstanders lacked a basic level of knowledge on the steering control system, in particular the transfer of steering and thrust control between stations,” according to the review. “The senior most officer responsible for these training standards lacked a general understanding of the procedure for transferring steering control between consoles.”

Perhaps most gallingly, it seemed clear to Navy investigators that there should have been enough time, with appropriate collision warning and inter-ship communication for the McCain, the Alnic MC, or both ships to have gotten out of the way of the other. The failure to perform this basic duty on the part of the American destroyer seemed to reflect a worrisome command culture.

The captain had declined to assign additional personnel to the bridge, protocol in high traffic areas, despite the recommendations of the ship’s executive officer, operations officer, and the navigator. The McCain’s Officer of the Deck at the time had not even bothered to attend the navigation briefing about transiting the Singapore Strait and Strait of Malacca the day before. And no one even questioned or looked to see whether an error had occurred in the transfer of controls between consoles immediately when the Helmsman declared they could no longer steer the ship, which could have resolved the issue earlier.

Soul searching

Again, the Navy noted that “no single person bears full responsibility for this incident,” in its report. The findings clearly speak to the already much reported on widespread issues impacting the service as a whole.

“These collisions, along with other similar incidents over the past year, indicated a need for the Navy to undertake a review of wider scope to better determine systemic causes,” Chief of Naval Operations Richardson noted in his cover sheet for the combined mishap reports. “The Navy’s Comprehensive Review of Surface Fleet Incidents, completed on 23 October 2017, represents the results of this effort.”

It seems almost certain that these sobering findings will lead to additional soul searching on the part of the Navy’s top leadership. Exactly how they will, or even can approach the situation, remains a separate issue, which we at The War Zone have already explored in depth here.

To add insult to injury, the McCain suffered a new crack in her hull while the heavy lift ship M/V Treasure was transporting the destroyer back to Japan for repairs. Treasure subsequently diverted to the Philippines so officials could inspect the new damage.

It’s obvious from the reviews of these accidents, though, that the Navy simply cannot afford to continue operating as it apparently has been doing for some time now.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com