It took a Congressional intervention to recently halt the Army’s controversial plans to dramatically cut the size of its largely unknown and underappreciated fleets of amphibious landing ships, landing craft, and various other vessels and maritime assets, which are also known as “the Army’s Navy.” This came shortly after The War Zone first reported that the General Frank S. Besson class Logistics Support Vessel USAV SSGT Robert T. Kuroda had come up for sale, before it quickly disappeared from the General Services Administration’s online auction house. By all indications, the service had been moving forward with the divestment of Kuroda and dozens of other so-called watercraft systems, as well as inactivating their associated units, despite having agreed months earlier to conduct an additional review of those decisions, which is still ongoing.

On July 15, 2019, Phil MacNaughton, a staffer for the House Armed Services Committee, reached out to the Army to say that legislators had concerns about the service’s watercraft restructure plans, according to Military.com. Four days earlier, Kuroda had appeared on the GSA Auctions website, along with the banner advertisement promising listings for the sale of 18 LCU-2000 landing craft, up to 36 LCM-8 landing craft, 20 tugs, and a pair of floating crane barges would be coming later in 2019 and in 2020. That ad also said that a second Logistics Support Vessel (LSV) might become available, as well.

By July 12, 2019, the Army had already pulled down the listing for Kuroda following The War Zone‘s report. You can read more about this ship, which is one the service’s largest and most capable, and the other LSVs, in this past War Zone profile. On July 26, 2019, the service’s senior leadership pulled the remaining auction listings and put watercraft divestments and associated unit inactivations on hold entirely.

“The Army is delaying implementation of its watercraft restructure plan, with respect to both vessels and units, until completion of an Office of the Secretary of Defense watercraft study which is expected to be concluded by the end of the fiscal year,” Matthew Leonard, a U.S. Army spokesperson had confirmed to The War Zone on July 30, 2019.

But it remains unclear why the Army was implementing its plan at that time at all. The first reports that the service was looking to significantly cut the size of its watercraft fleets emerged in January 2019, but a briefing The War Zone subsequently obtained shows that senior leaders had begun working to transform its watercraft force as early as June 2018.

This was a month after the Army, in coordination with U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM), had agreed, in principle, conduct the review of its watercraft restructure plan, Pentagon spokesperson Chris Sherwood told The War Zone in an Email. The Office of the Secretary of Defense had directed the service to perform this study after earlier discussions surrounding the Pentagon’s overall budget proposal for the 2020 Fiscal Year.

This is also in line with the information in the public version of the Pentagon’s 2020 Fiscal Year budget proposal that came out in March 2019. At that time, the Army’s portion thereof did not indicate any plans to significantly change the composition of the service’s watercraft fleets.

The watercraft review actually began in December 2018 or January 2019, according to Sherwood. The schedule for this study was and continues to be that the final report will be ready by the end of the 2019 Fiscal Year, which wraps up on Sept. 30, 2019.

This all makes good sense given that this was also around the time when the Pentagon was finalizing its latest National Military Strategy, which has a heavy emphasis on preparing for potential conflicts between the United States and “great power competitors,” such as Russia and China. INDOPACOM would already have had a significant interest in any decisions regarding amphibious and maritime logistics capabilities throughout the services given the “tyranny of distance” in the Pacific region.

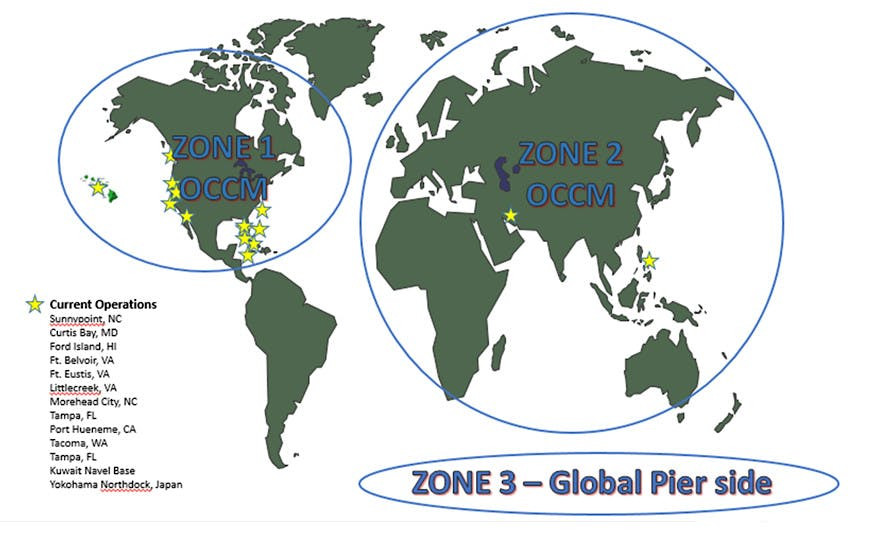

In particular, the Army’s Kuroda, along with her sister ship USAV Major General Robert Smalls, form a two-ship subclass of the General Frank S. Besson class that is further optimized for open-ocean operations. These two ships displace 1,800 tons more than the other six LSVs and have greatly increased range, along with other features to support their crews during long-distance missions. These vessels can also deposit their cargos right on a beach after arriving at their destination and do not have any need for established port facilities.

The LSVs, in general, along with the Army’s other watercraft fleets, which include elements forward-deployed in the Pacific, could help ease the strain on already highly in demand Navy amphibious and military sealift ships during a crisis. Army vessels could help unload ships at forward locations or otherwise move vehicles, personnel, and other cargo in littoral environments, such as within island chains. Those same capabilities extend to non-combat contingencies, such as responding to natural disasters.

Whether or not the Navy has or will have adequate capacity to replace the Army vessels has reportedly come up in the course of the ongoing review. The Navy’s new Expeditionary Transfer Dock logistics ships and Spearhead class Expeditionary Fast Transports do provide many similar capabilities. That service is also developing a replacement for its hovercraft Landing Craft Air Cushions (LCAC), which The War Zone has previously explored in detail.

However, Sherwood, the Pentagon spokesperson, made clear to The War Zone that the Army’s ongoing watercraft study only covers that service’s particular restructuring plan and whether it aligns with other planning elsewhere in the U.S. military. With all this in mind, it is not clear why the Army had continued to move ahead with divesting ships and inactivating units in the first place before the Pentagon-directed study was done.

Members of Congress certainly seemed to share the view that this could prove to be a short-sighted course of action. MacNaughton, the HASC staffer, told the Army that members of the Committee were worried that the service was making “irreversible” decisions without knowing the recommendations of its own review, according to Military.com.

The future of the Army’s watercraft fleets is still uncertain. Despite reports implying otherwise, the service has only put its restructuring plans on hold until the Pentagon-directed study is done. Beyond that, Mark Esper, who was Secretary of the Army when the service began moving forward with divesting vessels and inactivating units, is now Secretary of Defense.

The House’s version of the annual defense policy bill for the 2020 Fiscal Year, also known as the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), does seek to prohibit the Army from getting rid of any watercraft systems or associated units until it conducts another study of the plans through a federally-funded “research and development corporation,” such as RAND. Unfortunately, the House and the Senate are at odds over their respective versions of the NDAA, which could delay Congress from passing a final bill and it becoming law.

The end of the 2019 Fiscal Year, the due date for the current review of the watercraft restructure plans, is right around the corner. So we may not have to wait much longer to find out what the immediate future of the Army’s Navy looks like.

Update: 5:45pm EST—

After we published this story, U.S. Army spokesperson Matthew Leonard was able to confirm to The War Zone that the Pentagon-directed review of the Army’s watercraft restructuring plans began in December 2018, not June 2019, as Military.com had initially reported.

He also provided the following statement:

“A formal analysis that involves OSD [the Office of the Secretary of Defense], the Joint Staff, Army Headquarters, other Services and the combatant commands has been ongoing since December 2018. Initial analysis identified excess capability beyond existing requirements. Later, the Army decided to suspend watercraft transformation while we evaluate the overall watercraft requirements needed to support of the National Defense Strategy.”

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com