The U.S. Navy could scale back purchases of new destroyers, attack submarines, frigates, cargo ships, as well as retire early a number of cruisers and littoral combat ships, under a new budget plan taking shape in the Pentagon. The ostensible goal of the proposal is to free up funds for other shipbuilding efforts, including new fleets of unmanned surface and undersea vehicles, but the service is already finding itself in a battle with Congress over funding priorities before it has even finalized its pitch.

Defense News‘ David Larter explored the specifics of the plan, which was outlined in a memo from the White House’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) earlier this year, in a recent set of articles. Breaking Defense had first reported that a total of 24 ships, both new production vessels and existing hulls, could get cut from the Navy’s long-term shipbuilding and force structure plans over the next five to 10 years under this proposal.

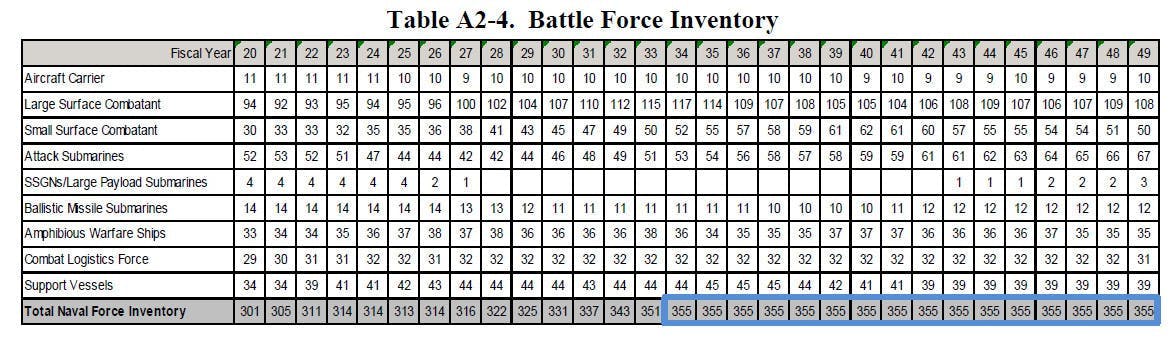

This same OMB document had also called on the Navy to craft a proposal for including unmanned platforms its so-called “battle force” inventory, which has historically only included larger, manned surface warships, submarines, and auxiliaries. The service has a standing goal to obtain a Battle Force with at least 355 ships, a benchmark Congress has enshrined in law. Earlier in December, Acting Secretary of the Navy Thomas Modly had issued his own memo saying that one of his five immediate objectives was finding a path to a 355-ship fleet within the next decade.

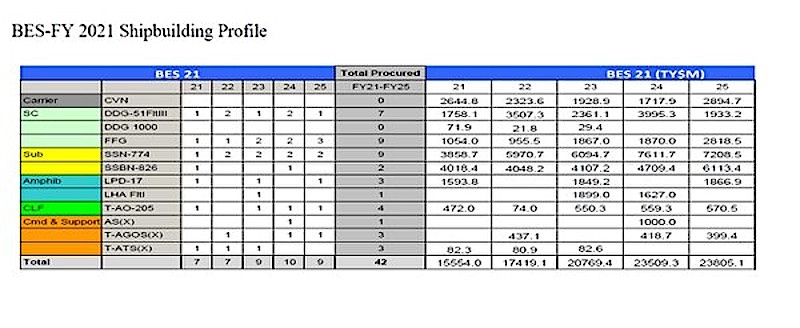

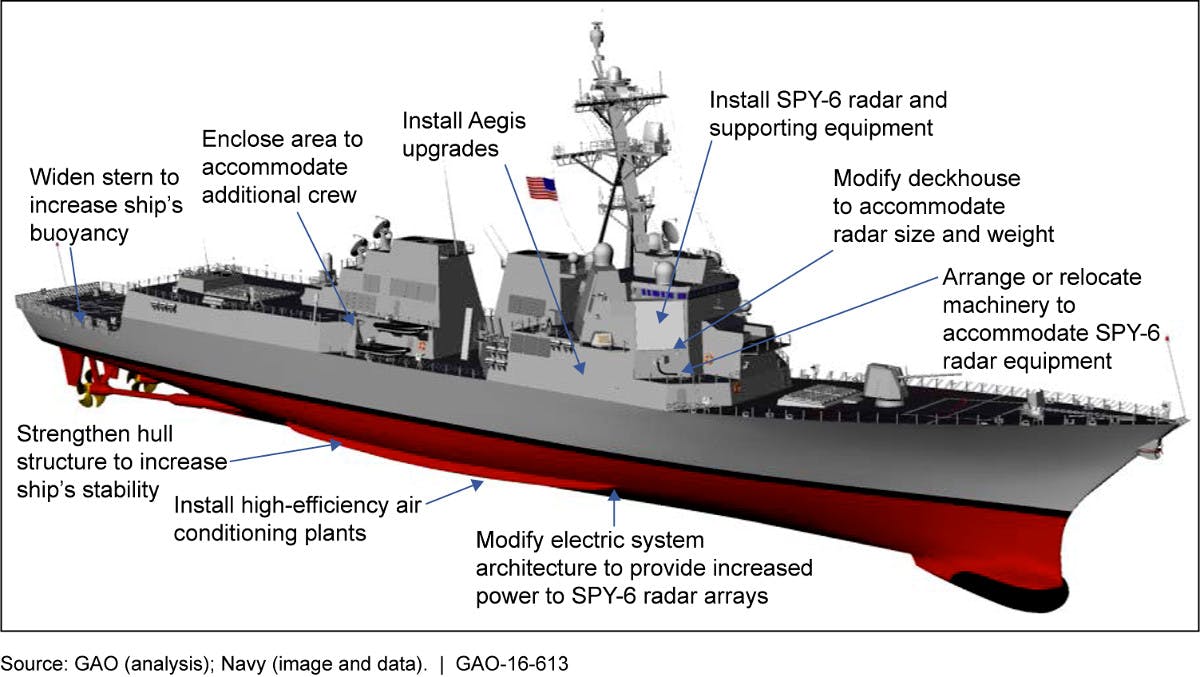

It’s not entirely clear how the present plan will service this goal, given that it could shrink the total size of the Battle Force from around 290 ships today to around 287 by 2025, according to Breaking Defense. The proposal includes cutting five of the 12 advanced Flight III Arleigh Burke class destroyers that the Navy expects to receive over the next five years, along with one Virginia class attack submarine and one FFG(X) frigate. The Navy has not yet chosen the design it will buy under the FFG(X) program, but wants to buy 20 examples of whatever ship it picks, in total, through 2030.

It’s worth noting that the Navy has been exploring the idea of acquiring a new Large Surface Combatant (LSC) in lieu of new destroyers since at least 2018, with senior officials saying in the past that hullform has reached its structural limits and cannot adequately support future requirements. At the same time, the LSC remains largely undefined and there have been indications that a new derivative of the Arleigh Burke may be the only logical path forward, which you can read about more in this previous War Zone piece.

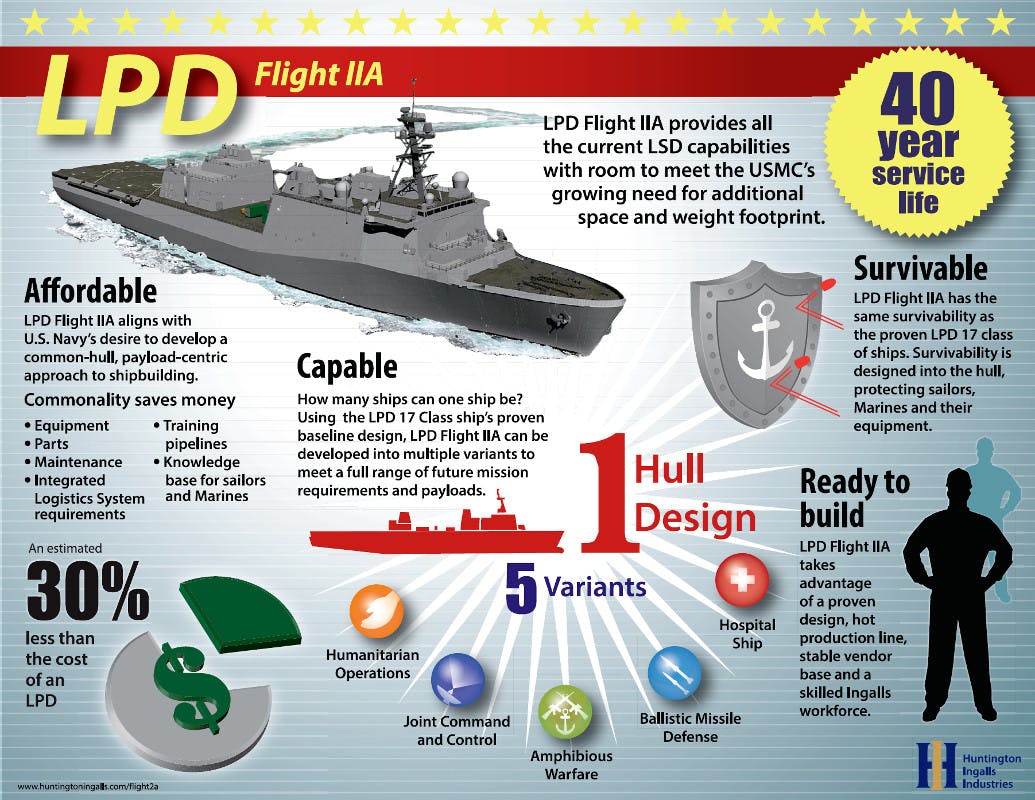

The OMB’s memo also called for a halt to the Common Hull Auxiliary Multi-Mission Platform (CHAMP) program and the development of a new alternative concept in its place. As its name implies, CHAMP has been focused on acquiring a fleet of auxiliaries with common hulls to take on a host of roles, including sealift, aviation logistics support, hospital, repair tender, and command and control. The ships currently performing these tasks are aging and increasingly difficult to operate and maintain. There have been growing fears that this could limit the availability of vital sealift capabilities, in particular, in a future large scale conflict, something you can read about in much greater detail in these past War Zone stories. Right now, the Navy expects to get its first CHAMP ship, a sealift variant, in 2025.

Beyond the cuts to new shipbuilding, the proposal also calls for increasing the speed at which the Navy retires its Ticonderoga class cruisers. The plan in OMB’s memo would see 13 of those warships leave service by 2025, up from the nine presently scheduled to head into mothballs in that same timeframe.

In addition, the Navy would retire the first two examples of both the Freedom and Independence class Littoral Combat Ships. These ships have already been relegated to training and test roles, but the service had planned to put them together with other manned and unmanned surface combatants in its new Surface Development Squadron One. This unit stood up earlier this year and is already set to be responsible for all three of the Zumwalt class stealth destroyers, two of which are already in service, as well as the Sea Hunter experimental unmanned surface vessels.

It’s important to point out that the plan in the OMB memo is not necessarily the final proposal that the Navy will include in its budget request for the 2021 Fiscal Year, a public version of which should come out sometime between February and March 2020. The exact justifications for the spending shifts and how the service expects to fill the resulting force structure gaps remain to be seen.

However, many of the decisions already on the table have begun to incite the ire of legislators who will have a final say over the budget. This opposition is likely to grow in the near term. For instance, Congress has pushed back against retiring Ticonderoga class cruisers repeatedly in recent years. The Arleigh Burkes are set to continue to be the Navy’s primary surface combatant for years to come, which could make cuts there another hard sell, especially with the Large Surface Combatant still so undefined. The Virginia class is equally central to the service’s future submarine force plans.

It may be easier to get support for cutting the original four Littoral Combat Ships, which, as noted, have already been sidelined and assigned only non-combat roles, but many legislators remain proponents of the LCS program despite the continually underwhelming performance of the ships. Congress has also been skeptical of the FFG(X) program, especially how heavily it has been considering non-U.S. warship designs. Lawmakers have already pushed through legislation that could upend those plans by requiring the use of a certain amount of American-made parts and materials, something you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone piece.

In addition, there have also been general concerns in recent years about ensuring the stability of the shipbuilding industrial base, which could be threatened by major changes in production totals and timeframes. Building warships and submarines is an inherently long lead time affair that involves establishing complex supply chains and recruiting and retaining highly training workforces. Legislators representing districts where the ships in question are built simply have interests in preserving the jobs and other economic benefits that come along with keeping shipyards working without significant interruptions, too. All of this applies to major overhauls and other regular maintenance work, as well.

All told, the proposal OMB has outlined seems almost guaranteed to generate the kind of criticism from Congress that the Navy most recently received with its curious plan to retire the Nimitz class aircraft carrier USS Harry S. Truman years ahead of schedule. The service eventually abandoned that idea in the face of a massive backlash from lawmakers. The OMB memo reportedly shows that the White House actually rejected a second attempt from the Navy to try and cut Truman from the budget.

As was the case with the attempt to retire Truman early, all of this raises questions about whether the real goal of this latest proposal is to try to convince Congress to increase funding for shipbuilding efforts across the board. At the end of the debacle, legislators agreed to a block buy of two Ford class carriers and to pay for the Truman‘s overhaul to keep it in service.

The Navy continues to argue that it needs to purchase a large number of new ships and submarines and that it has to make hard choices to work within existing budget constraints. In particular, the acquisition of new and extremely expensive

Columbia class ballistic missile submarines, critical to ensuring the United States’ nuclear deterrent capabilities, is repeatedly cited as a core issue in long-term budget planning. Congress has already allowed the Pentagon and the Navy to use novel funding mechanisms to try to mitigate the impact of buying these submarines has on other shipbuilding priorities, but concerns remain about whether yet more funding may be necessary to keep production of the Columbias

The costs the Navy has already incurred as it struggles to get the first-in-class aircraft carrier USS Gerald R. Ford

ready for actual operations, which are likely to continue to grow at least in the near term, has been another drain on shipbuilding resources. The service has taken steps to try to mitigate cost growth in the acquisition of future Ford class carriers, notably the aforementioned block buy, and President Donald Trump recently enacted new cost caps on those ships with the signing of the latest National Defense Authorization Act policy bill.

Whatever the Navy’s exact plans might be, criticism of the still unfinalized budget proposal has already begun to come from members of Congress in Mississippi, which is home to a number of shipyards that could see major impacts if the plan goes ahead. Many legislators have expressed concern about the speed with which the service is moving ahead with what they feel are unproven unmanned platforms, as well as other technologies, despite the enormous capability and cost benefits they promise in support of increasingly distributed operations, especially in the Pacific Region. The War Zone has explored these issues in depth on multiple occasions in the past.

“I’d remind the Pentagon that through the authorization and appropriations processes, Congress will ultimately decide the sizes of our manned and unmanned fleets,” Representative Steven Palazzo, a Republican, said in a statement. “Now more than ever we need these multi-mission ships to fight against the real threats from countries like Russia and China. I find it doubtful that Congress would buy into this plan to limit construction of destroyers while we are actively working to rebuild our military.”

“The Navy’s goal of 355 ships is the law of the land, and I am committed to working with President Trump to ensure our shipbuilders on the Mississippi Gulf Coast have the resources they need to remain the premier supplier of Navy ships,” Senator Roger Wicker, another Republican, who was responsible for enshrining the 355-ship requirement in law, said in a separate statement. “Destroyers have been the backbone of our Navy’s fleet for decades, and I do not see that changing any time soon.”

All told, the Navy is clearly in the process of ironing out a new vision for how it will build a 355-ship fleet and what types of ships it will include in that force in the years to come. At the same time, the service is already butting heads with Congress over exactly what mix of ships and capabilities represents the best path forward to meet that long-standing goal.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com