The Navy’s top admiral said a recent walk through a Virginia class submarine Command and Control Systems Module (CCSM) under construction offered a vivid glimpse into how the Navy can speed building out the future FF(X) frigate. Having companies, both domestic and potentially foreign, construct modules that can later be plugged into hulls by major shipyards can dramatically increase efficiency, Adm. Daryl Caudle, the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) said. His observations come as the U.S. is struggling to get anywhere near catching up to China in the number of naval vessels it is pumping out per year.

The process is called distributed shipbuilding. While not a new concept, it is used on more complex vessels, like SSNs, SSBNs, DDGs and LPDs. Now the Navy is looking to use this concept for its rebooted FF(X) frigate program, Caudle said. He pointed to the construction of Virginia class fast-attack submarines as a prime example of how that works.

“I was just down on the Gulf Coast to see how they build three modules there for [the] Virginia class and they’re going to start building for Columbia as well,” Caudle told a small group of reporters, including from The War Zone, of his recent visit to the Austal USA shipyard in Mobile, Alabama. The company is building and outfitting CCSMs for three future Virginia class boats and Electronic Deck Modules (EDM) for the Virginia– and Columbia-class nuclear ballistic missile submarine programs.

“One of the main modules they build is the entire Command and Control suite for Virginia class,” he explained during a media panel at the Surface Navy Association (SNA) annual symposium on Wednesday. “And when you see that module… they had one that was almost ready to be shipped up to Quonset Point. It’s like walking into a Virginia class submarine control room. The thing is completely done, built, and the only thing that’s missing is really the computers that we put in for the sonar and fire control system.”

Austal construction of the modules “offloaded hundreds of thousands of man-hours off Electric Boat and utilized additional capacity of that yard to do that,” Caudle said. “So without those types of changes and how we actually optimize all the yards to go do this, it will be challenging.”

While distributed shipbuilding is being eyed for the FF(X) program, the first ship in the class won’t be built that way. The U.S. has a lot of work to do to make that happen for the rest of the class, Caudle posited.

“…there’s going to have to be some paradigm shifts with things like modularity,” the CNO said. “We are, I think, at just the tip of the iceberg on how we’re starting to utilize modularity more effectively.”

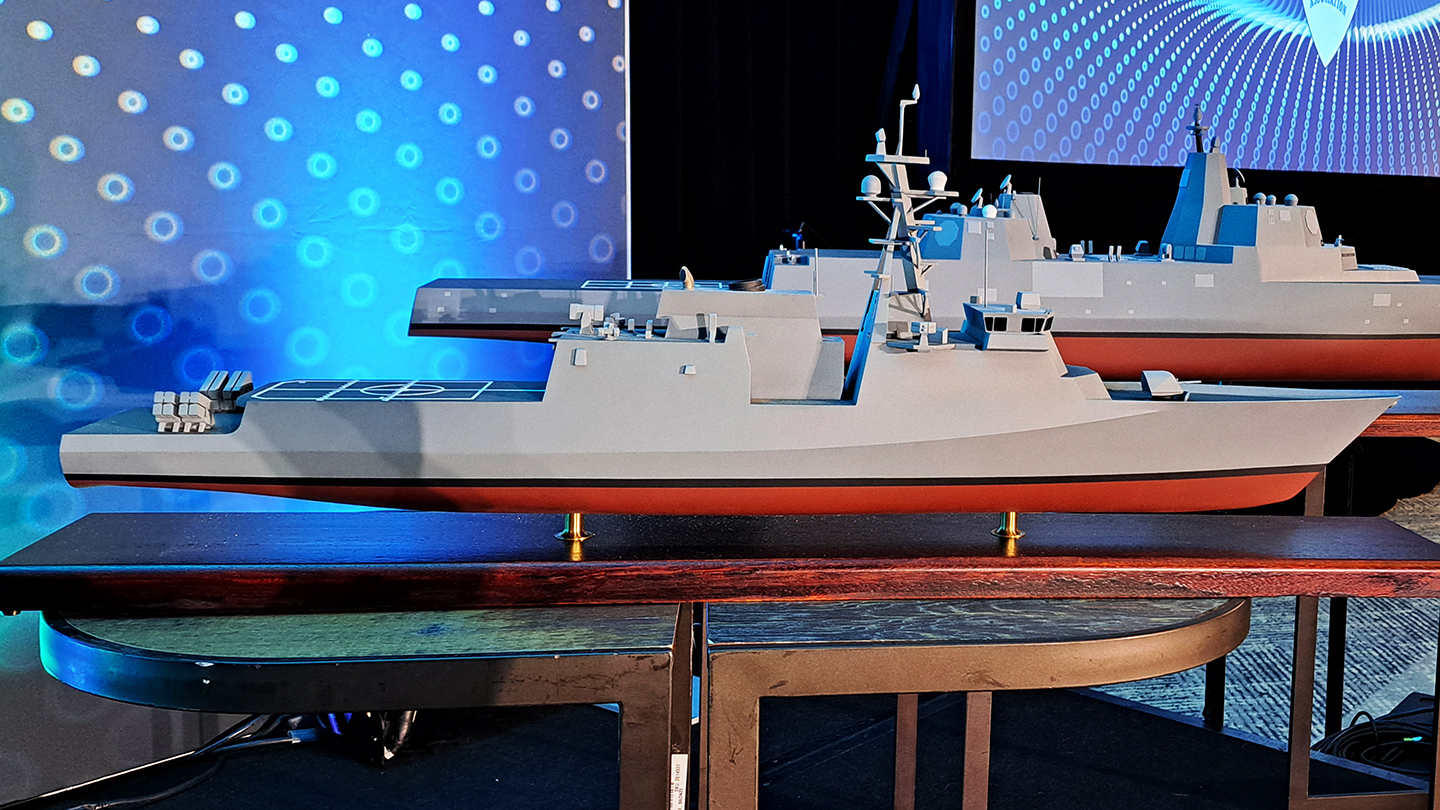

In December, the Navy announced it would acquire the frigates, to be built on a design based on the U.S. Coast Guard’s Legend class National Security Cutter. The new warships, the first of which is set to be launched in 2028, are intended to fill the gap left by the cancellation of the abortive Constellation class frigate program.

The FF(X) was launched to provide a quick way to replace the Constellation class, however, the design is controversial because it lacks a vertical launch system for missiles, drastically reducing its firepower, as well as other features. You can read more about that in our story here.

The first FF(X) was awarded to HII/Ingalls on a sole-source basis and scheduled to be launched by 2028. After that, the procurement process will be opened up to competitors.

Caudle says that the distributed shipbuilding approach could spread out the workload from major yards to smaller ones, which are more plentiful. That will help the Navy speed up construction of additional ships in this class, he proffered. This will also help to keep these yards working and decrease the political vulnerability of the program by spreading out the work across different Congressional districts.

“So let’s say that one of the yards down on the Gulf Coast starts building the frigate and they’re the main contract that the Navy goes with for that,” the CNO said. “Nothing prevents other Gulf Coast shipyards—which there are many, I want to say there’s probably 20 plus—from being in the business of building some part or whole of a module for that frigate. And when you bring in the ability of the yard to utilize some of its additional capacity to be part of the modularity design of that, then what you end up with [is] the lead yard is more in an assembly process than having to build it all from scratch.”

Foreign shipbuilders are further along in the process, the CNO noted.

“A lot of the foreign partners that we work with and discuss how they do shipbuilding are really all-in on modularity, and we traditionally have not built ships that way until recently,” he added. “And so I think the actual methodology of the workflow within a shipyard is not completely tuned for a modular approach yet in all of our yards. Until you get there, then the fungibility of the yard to support each other won’t be there. So I’m not completely optimized.”

Foreign shipyards could potentially build modules for the frigate and other ships as well, Caudle postulated. That would be in line with President Donald Trump’s interest in buying ships made abroad to help to make up a yawning gap with China, which has been assessed to have a whopping 200-times larger shipbuilding capacity than the United States.

As we have explained in past reporting, both South Korea and Japan are building vessels now that are related to the Arleigh Burke class, which currently serves as the backbone of the U.S. Navy. This puts both countries in a unique position to build U.S.-spec Burke destroyers, or at least substantial parts of them. They also have other models that are unlike those currently in the fleet, including smaller warships. Logistics ships and sea bases are also well within their capabilities.

“Certainly I do think there’s a role for foreign yards to play in our shipbuilding initiatives to add capacity,” Caudle explained. “I think the capacity that foreign builders could bring to bear is extremely important to think about.”

“That might look like some auxiliary ships that we could get approval to do in totality,” Caudle stated. “And it could be combat ships that can be done in part.”

While foreign shipyards could help the U.S. speed up construction, there are challenges to making that happen.

“When you work with a foreign partner, they either had to have exquisite access to our supply system, and that’s the IT system and the infrastructure to order parts and tap our supply system, or they’re going to use their own indigenous system,” the CNO noted.

A foreign shipbuilder using their own systems, especially those from non-English-speaking countries, adds another layer of complexity, Caudle said.

“So all that needs to be worked out. But I do think that … it needs to be explored, and I view it as a bridging strategy till we get our industrial base where it needs to be to do it organically.”

Contact the author: howard@thewarzone.com