The U.S. Navy says it had gotten the average cost of each of its future Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines, or SSBNs, down to almost $7.2 billion and that the project is on schedule. The latter point is especially important since the service remains concerned about whether shipyards can deliver boats on time while its existing subs are also struggling to meet operational demands due to a major maintenance backlog.

U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Michal Jabaley, who is the Program Executive Officer for Submarines made the announcement at the Naval Submarine League’s annual conference earlier in November 2017. The service is planning to buy 12 Columbia-class boats in total to replace the bulk of the Cold War-era Ohio-class, with the lead ship entering service in 2031 if everything continues on schedule.

“Through innovative legislative authority and contracting techniques, we’ve already reduced cost by $80 million per hull, to bring [average procurement unit down to $7.21 [billion],” Jabaley said. “So that was a combination of missile tube continuous production … and advance construction, which is pulling key construction activities to the left. Really the focus of that was to reduce the risk of not delivering on time, but it had an added benefit of savings as well.”

The special authorities the rear admiral was talking about include Congressional approval of certain procurement plans and the creation of a unique funding stream, known as the National Sea-Based Deterrence Fund. Jabaley said he hoped the experience would convince legislators to sign off on additional, non-traditional purchasing mechanisms to help drive the unit cost below $7 billion. The estimated cost of the boats in 2010 was a little more than $6 billion and the program has a unit cost cap of $8 billion.

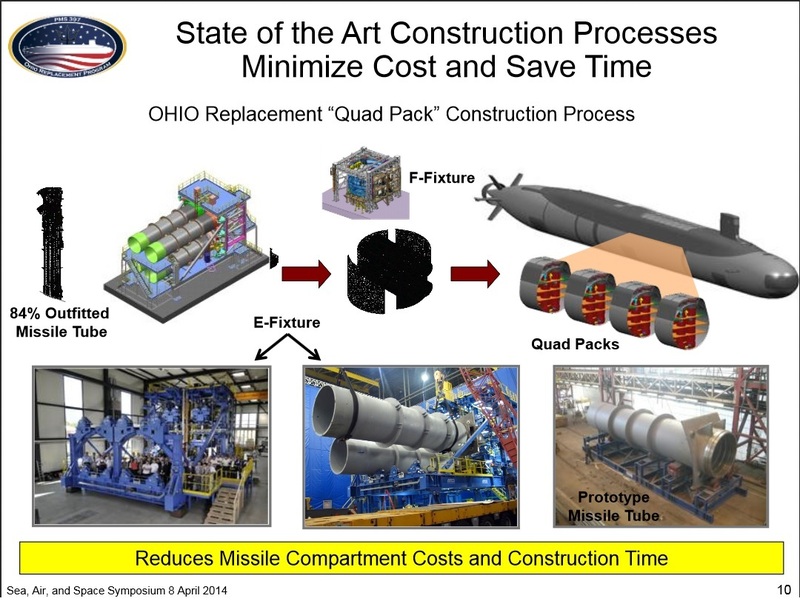

The U.S. Navy is already buying missile tube “quad packs” for the Columbia-class at a constant rate. In the past, the service had purchased them only when the construction of the submarine itself reached the appropriate point, leading to small, irregular, and costly orders.

In addition, it is sharing the contracts with the United Kingdom, which is using the same launch tubes on its up-coming Dreadnaught-class SSBNs. Both American and British ships will be armed with the Trident D-5 missile.

Jabaley’s office has saved money by using as many systems as possible from the Virginia-class attack submarine and the Ford-class aircraft carrier on the Columbia design. Congress was therefore amendable to buying these components in cheaper, larger purchases.

The special fund has proven more controversial. In order to try and make sure the new missile boats didn’t take money and resources away from conventional surface ships and submarines, Congress created an entirely unique budget line for the program.

Shipbuilding, as a general rule, is a time intensive affair that needs significant upfront investments in both infrastructure and a skilled workforce, something that goes double for submarines, which are typically more complex than surface ships. Once the shipyards get going on a particular class, though, it’s easier for them to sustain production and steadily reduce costs, as long as there is demand and adequate funds.

So making sure Columbia didn’t disrupt other shipbuilding programs made sense, at least in theory, but only if it came along with an increase to the overall defense budget, which it did not. Lawmakers had historically rejected this kind of budget trickery, which only serves to redirect existing money into different projects, and there were reports that senior Navy officials, including Admiral John Richardson, the present Chief of Naval Operations, the service’s top officer, might have illegally lobbied for its creation.

Without any extra money in the budget overall, the fund effectively diverted funds to the Navy, while imposing cuts on other the services. As such, there are increasingly serious concerns about the service’s shipbuilding plans and the ability of American shipyards to meet those demands. In September 2017, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a video presentation exploring the worrying decay of Navy shipyards.

The top Congressional watchdog noted that the Navy used to have 13 of its own shipyards for shipbuilding and maintenance functions, but now only has four, which is completely inadequate to sustain a modern naval force. The service’s dry docks are, on average, 89 years old and simply not built to handle the needs of modern ships. The situation had already created at least a $5 billion backlog in repairs and it could take decades to create new and appropriate infrastructure. This lack of propriety capacity in turn put more pressure on private contractors to make up for the shortfalls while also building new surface ships and submarines.

So it’s not surprising that, in an interview with USNI News on the sidelines of the 2017 Naval Submarine League conference, U.S. Navy Vice Admiral David Johnson strongly implied that the industrial capacity issue would impact whether or not the Columbias arrive on time, independent of other factors. The vice admiral presently serves as the principal military deputy to the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development, and Acquisition and has previously been in charge of the Virginia-class attack submarine program and head of the Program Executive Office for Submarines.

The officer stressed that getting the total time it takes General Dynamics Electric Boat and Huntington Ingalls Industries’ Newport News Shipbuilding to build Virginias down to 60 months – not counting three months of routine testing and another three months of pre-delivery checks – will be absolutely critical for the service’s submarine production plans. “We have to achieve that if we’re actually going to do Columbia on time and even have anybody want to discuss potentially adding a third ship that’s a Virginia-class.”

When the Navy started buying Virginias, the scheduled was one delivery each year. In 2011, the service moved expand this to two a year and there is a hope that shipyards might be able to bump this number up three boats annually the future.

This might not be as much of a stretch as one might imagine. The Virginia-class has been a model program, both in terms of efficiency and cost. But that doesn’t mean it’s been immune to the larger shipbuilding issues. The USS Washington entered service behind schedule in October 2017. The future USS Colorado was supposed to be ready in two months earlier, but will now arrive some time in 2018.

The decision to try and acquire two of the submarines each year has put a noticeable strain on both shipyards and the subcontractors who supply the necessary components. To keep up with this pace, the Navy has also been pushing steadily toward that 60-month goal for total construction time in its contracting requirements.

“Both shipbuilders hired additional people to account for the increase to two submarines per year,” Rear Admiral Jabaley told Defense News in March 2017. “As a result, obviously when you bring in an influx of new people your level of experience goes down.”

That sort of experience gap can lead to mistakes, which turn into schedule slips. With the production plans so tightly packed already, even minor issues have the potential to snowball into larger problems.

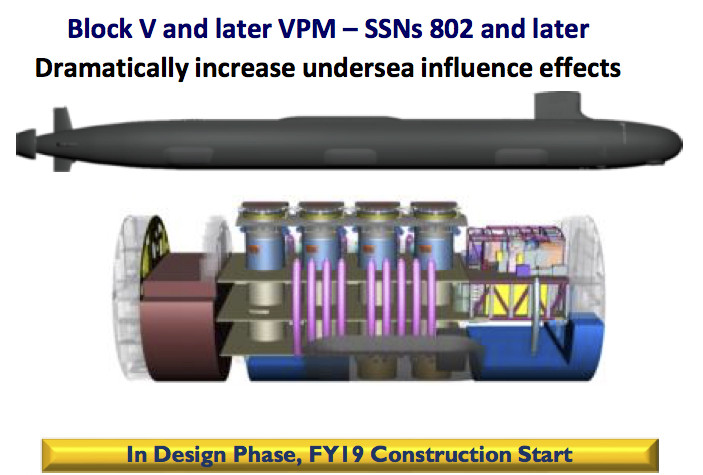

On top of that, General Dynamics Electric Boat and Huntington Ingalls Industries’ Newport News Shipbuilding are gearing up to start production of both Block V Virginia-class production in 2019 and the Columbias in 2021. The Block V boats will have the so-called Virginia Payload Module (VPM), an additional section with four more missile tubes, each one able to accommodate seven Tomahawk land attack cruise missiles.

The addition will add nearly $400 million to the price tag for each one of the attack subs and at least some amount of additional work, even though the systems involved are fully mature. This is undoubtedly why Vice Admiral Johnson is so adamant about getting the existing production schedule down to 60 months, since the Virginias could experience new, unforeseen delays when work on Block V starts up, which could possibly cascade down into the separate Columbia production schedule. The new SSBNs are almost certain to hit snags of their own, something that is almost unavoidable when developing and building new ships.

In addition, the goal is for the Block V boats to be able to take over for the four conventionally armed Ohio-class guided missile submarines, or SSGNs, specifically to free up the Columbia-class from having to perform this mission. The new missile boats could conduct conventional missions in addition to their nuclear-armed deterrence patrols, but it would put additional strain on the proposed 12 ships – something the Navy could, of course, mitigate, by expanding the size of the class and adding conventionally SSGN armed variants. The service is already working on a conventional, hypersonic boost glide weapon for the Ohio-class that could easily end up ported over to the new missile boats and increase their overall flexibility.

There are presently 18 SSBN Ohios in service, including the four conventional SSGNs. Each SSBN has 24 missiles tubes compared to the 16 on the forthcoming Columbias.

The potential for trouble doesn’t stop when the ships enter service, either. In October 2017, Breaking Defense reported that 15 Los Angeles– and Virginia-class attack submarines had been sitting idle due to a growing backlog of scheduled maintenance work, underscoring the worrying reality GAO had described a month earlier. The subs had been out of action for a combined period of 177 months. The USS Boise had spent the longest time pierside, with the Navy expecting her to be laid up for a total of 31 months.

“If you have a submarine that’s tied up in the shipyard, then obviously they’re not operating,” U.S. Navy Vice Admiral Joseph Tofalo, the service’s top submarine officer, told Breaking Defense at the Naval Submarine League conference. “It’s probably most manifest in our ability to surge in time of crisis. We meet our … demand on a day to day basis, but the impact would be, if there’s a crisis, then your surge tank is low.”

The Navy as a whole has been beset by shortages of ships, manpower, and other resources, contributing factors in a spate of deadly accidents earlier in 2017 in the Pacific region. Tafalo stressed to Breaking Defense that this readiness crisis was far less pronounced in the submarine community and that submarines were very close to the expected average length of a patrol, which is six months.

The service is looking to mitigate these issues and has announced a major review of operations in the wake of the aforementioned mishaps, which resulted in the deaths of a total of 17 sailors. Budget caps and cuts, though, continue to play a major role in limiting what the Navy can do to improve the situation. GAO has already said it thinks the service’s $5 billion estimate of the cost of the maintenance backlog is low and that its suggestion that it would take nearly two decades to reestablish appropriate organic naval shipyard infrastructure is optimistic.

Congress is working to pass a new defense budget, but it is likely to take more than one fiscal cycle to begin moving things in the right direction. At the same time, the Navy will have to make sure it keeps its existing submarine production and maintenance as close to the planned schedule as possible, so as not to incur additional costs and delays, which would in turn require even more additional funds.

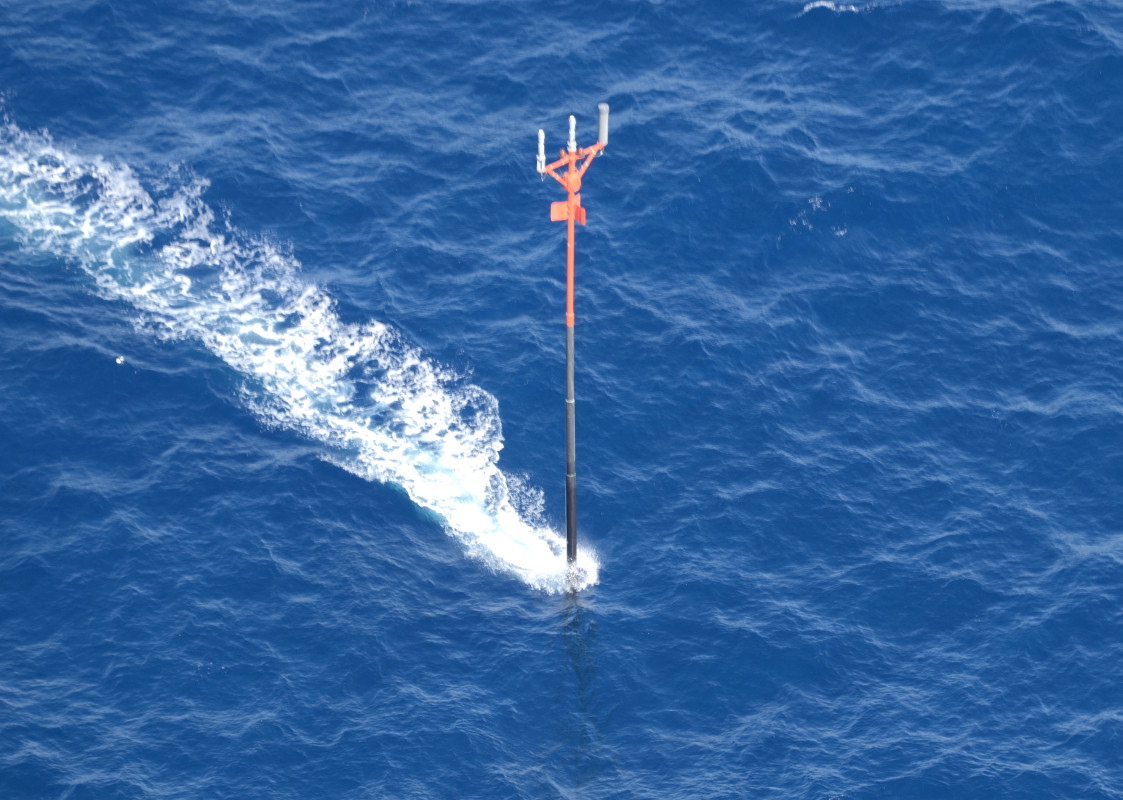

Having an adequate number of submarines ready to go in a crisis is exceptionally important, as well, given their overall flexibility and ability to operate largely unseen for protracted periods of time. This makes them capable of striking time-sensitive targets with less warning than many other platforms – something President Donald Trump has been particularly keen to emphasize with regards to a possible confrontation with North Korea.

“Currently stationed in the vicinity of this peninsula are the three largest aircraft carriers in the world,” the American president boasted to South Korea’s National Assembly during a speech on Nov. 7, 2017. “In addition, we have nuclear submarines appropriately positioned.”

The Navy seems to be doing its best to make sure that stays the case both in East Asia and around the world. Unfortunately, the situation is likely unsustainable unless current trends change dramatically.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com