The U.S. Navy’s future Constellation class frigates are set to be at least 759 metric tons (close to 867 U.S. tons) heavier than expected, a 13 percent increase over earlier estimates. Concerns have previously been raised about how weight growth with the Constellation class design, which was still being finalized as of April, could negatively impact the ships’ top speed and other capabilities. Overall, the frigate program, the entire point of which was to leverage an existing in-production design to help reduce risk and speed up delivery, remains years behind schedule and at risk of ballooning costs.

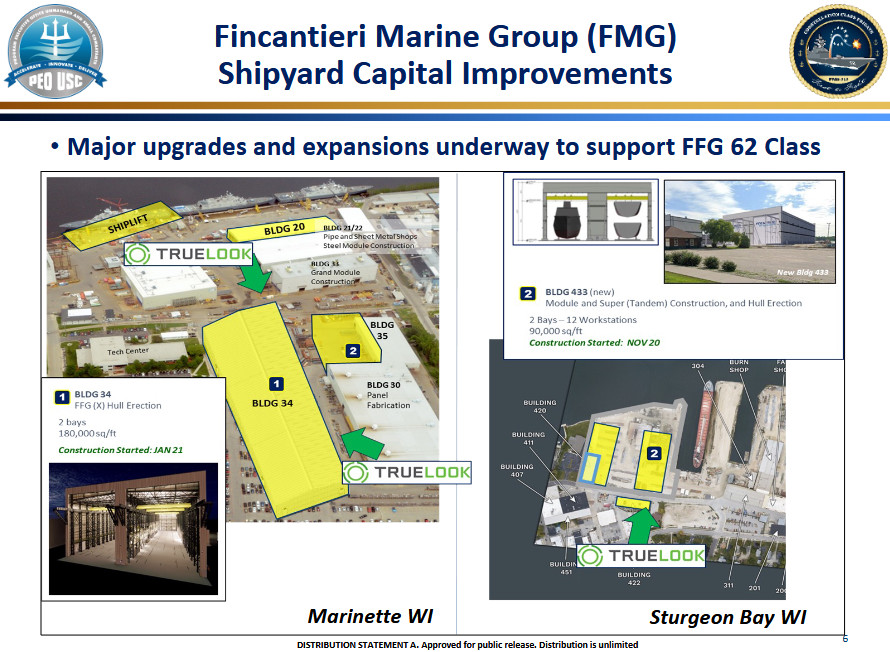

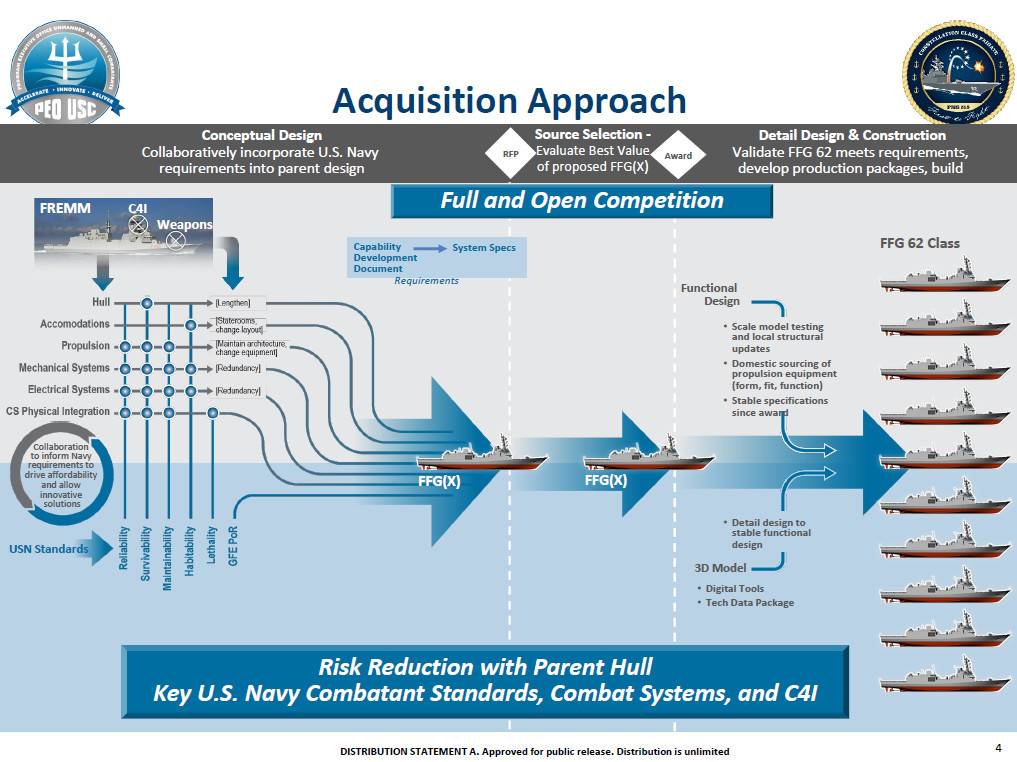

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), a Congressional watchdog, included the new details about the Constellation class design’s weight growth and other updates about the program in an annual assessment of major procurement efforts across the U.S. military released today. The U.S. Navy chose Marinette Marine in Wisconsin, a wholly owned subsidiary of Italy’s Fincantieri, to build the new frigates in 2020. The ship’s core design is derived from the Franco-Italian Fregata Europea Multi-Missione (FREMM).

The Navy currently expects to take delivery of the first-in-class USS Constellation in 2029, three years behind schedule. The service has, to date, awarded Marinette Marine contracts to build six Constellation class frigates.

“In October 2024, the Navy reported 759 metric tons of weight growth from initial estimates – nearly a 13 percent increase – due in part to the underestimation of applying Navy technical requirements to a foreign ship design,” per GAO’s new report. “We previously reported that unplanned weight growth during ship construction can compromise ship capabilities, as the fleet seeks to alter and improve initial capabilities over the planned decades-long service life of the ship. Such alterations may leave frigates less combat capable, limit the ability to add capabilities to address evolving threats, and reduce planned service lives.”

It is unclear from the GAO report whether this 759 metric ton increase is in terms of gross weight or displacement, and whether or not it is a total figure or additive on top of previous growth. By 2021, it had already emerged that the Constellation class’ displacement was expected to be around 500 tons greater than that of the parent FREMM design, ostensibly to account “for margins and future growth.” The targeted displacement of these vessels, at least originally, was 7,291 tons. The new Navy frigates will also be physically longer and wider. As it stands now, there is only some 15 percent commonality in the Constellation and FREMM designs, compared to the original goal of 85 percent.

“Navy personnel are working with the shipbuilder to reduce the ship’s weight, but weight growth has only become more pronounced over the last year as the program further developed the frigate design,” the report also notes.

This point speaks to further complications arising from the fact that, at least as of April of this year, the Constellation class design still had yet to be finalized. This is despite the construction of the future USS Constellation already being underway. As of April, construction of the ship was approximately 10 percent complete.

“In response to a recommendation we made in our May 2024 report, the program restructured its functional design metrics to more closely align with actual design progress. As a result, the program concluded that its functional design progress is significantly less than the 92 percent complete it reported in August 2023,” according to GAO’s latest assessment. “As of December 2024, the program reported that the functional design was 70 percent complete, as measured with the restructured design metrics. Although program officials expect to achieve a stable basic and functional design by late spring 2025, the program has yet to achieve its planned rate of design progress to meet this goal.”

“The Navy stated that it chartered an independent review team to perform a holistic assessment of the shipbuilder’s production schedules, identify key issues, and recommend actions,” the report adds. “Additionally, the Navy reported that it increased design and production efforts by bringing in both Navy and contracted engineering design support personnel at the shipbuilder’s site to bolster and accelerate design stability completion and ramp-up of production.”

GAO says the Navy declined to provide an estimated date for reaching initial operational capability with the Constellation class with this review still underway.

In the past, the Navy has heavily blamed shipyard capacity and workforce issues – real and increasingly dire problems for the service in general that you can read more about here – for hampering work on the Constellation class. The service has also cited macroeconomic disruptions, such as inflation, stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic and other global crises, as being important factors.

“So I was at Fincantieri [Marinette] Marine two weeks ago. I was very impressed by the investments they’ve made in their shipyard and things they’ve done in an attempt to modernize,” Secretary of the Navy John Phelan told members of the Senate Armed Services Committee yesterday. “And I think there’s some things that some of the other shipyards can actually take and potentially adapt.”

In November 2024, the Navy began formally seeking information about options for bringing in a second shipyard to help with Constellation class production, a possibility that had previously been raised. As of January, the service was still assessing the responses it had received, per GAO.

At the same time, it is hard not to see the Constellation class’ continued weight growth and persistent lack of a stable design as going beyond shipyard issues, and having undercut the central focus of the program. As noted, choosing an in-production parent design to serve as the basis for the new frigates was explicitly intended to avoid many of the problems the Navy is facing now.

“The Constellation class frigate will be three years late and will take nearly 10 years to deliver the lead ship. This is largely because the Navy cannot keep its requirements steady. Almost 70 percent of the requirements have changed since the Navy signed a contract,” Sen. Roger Wicker, a Mississippi Republican, chided Navy officials at a hearing last year. “So the outcome that we see today is no surprise. This is not an example of the industry underperforming. This is senior officials unable to manage a program. This is acquisition malpractice and a terrible waste of time and resources.”

All of this has already contributed to questions about the future of the Constellation class, overall.

“The question is, are we at a point where we either quickly recover and get back on track with this, get back to schedule, get back to budget – I don’t know that you could make up schedule – or do you say, maybe we’re too far along with this, and we go in a different direction,” Rep. Rob Wittman, a Virginia Republican, said during a panel discussion at the Navy League’s Sea Air Space 2025 in April. “The Navy is going to have to ask that question now. It can’t push it off in the future.”

At the Senate Armed Services Committee hearing yesterday, Wicker noted that procurement of additional Constellation frigates was halted last year “because of design instability” and that the Navy did not appear to be requesting funding for any of the ships in the 2026 Fiscal Year. A public version of the U.S. defense budget request for the upcoming fiscal cycle has not yet been released.

“As it relates to the [Constellation class] frigate and in the force, [we’re] still evaluating that, we’re still trying to understand how it fits, when we can get it fixed, [and] what the plans are for it,” Phelan said at yesterday’s Senate Armed Services Committee hearing. “And so I will come see you soon as we get a handle on that. But it is something we’re looking at very hard. And I do think that the shipbuilder there has done a great job. And so we need to figure out how to keep that going and add to it and understand that.”

More details about the Navy’s exact plans for the future of the Constellation class are likely to come when a public version of the Navy’s budget request for the 2026 Fiscal Year is finally released. In the meantime, the core design has already diverged significantly in terms of weight and other aspects from what was originally expected.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com