The U.S. Navy is putting major emphasis on containerized weapons and other systems to make up for limitations in the built-in capabilities of its forthcoming FF(X) frigates. The design’s lack of an integrated Vertical Launch System (VLS), which TWZ was first to confirm, and other capabilities, has prompted questions and criticism. As it stands now, the FF(X)s will have nearly the same armament installed as the Navy’s much-maligned Littoral Combat Ships (LCS).

Navy officials shared new details about the FF(X) design, which is derived from the U.S. Coast Guard’s Legend class National Security Cutter (NSC), at the Surface Navy Association’s (SNA) annual symposium this week, at which TWZ was in attendance. The service rolled out the new frigate program last month. The announcement followed the cancellation of the abortive Constellation class program, which had been intended to address the chronic shortcomings of the LCSs, but had turned into its own boondoggle.

“We are pursuing a design [for FF(X)] that is producible, it has been proven, it is operationally in use today, and it will evolve,” Chris Miller, Executive Director at Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA), told attendees at the SNA conference yesterday.

The Navy’s FF(X) frigate design, as it exists now, is 421 feet long, has a beam (the width of the hull at its widest point) of 54 feet, and displaces 4,750 tons. It can sail at up to 28 knots, has a range of 12,000 nautical miles, and an endurance of 60 days. For comparison, the Coast Guard says its NSCs are 418 feet in length, have a 54-foot beam, and a displacement of 4,500 tons. The previously planned Constellation class frigate was a significantly larger ship that displaced thousands of tons more.

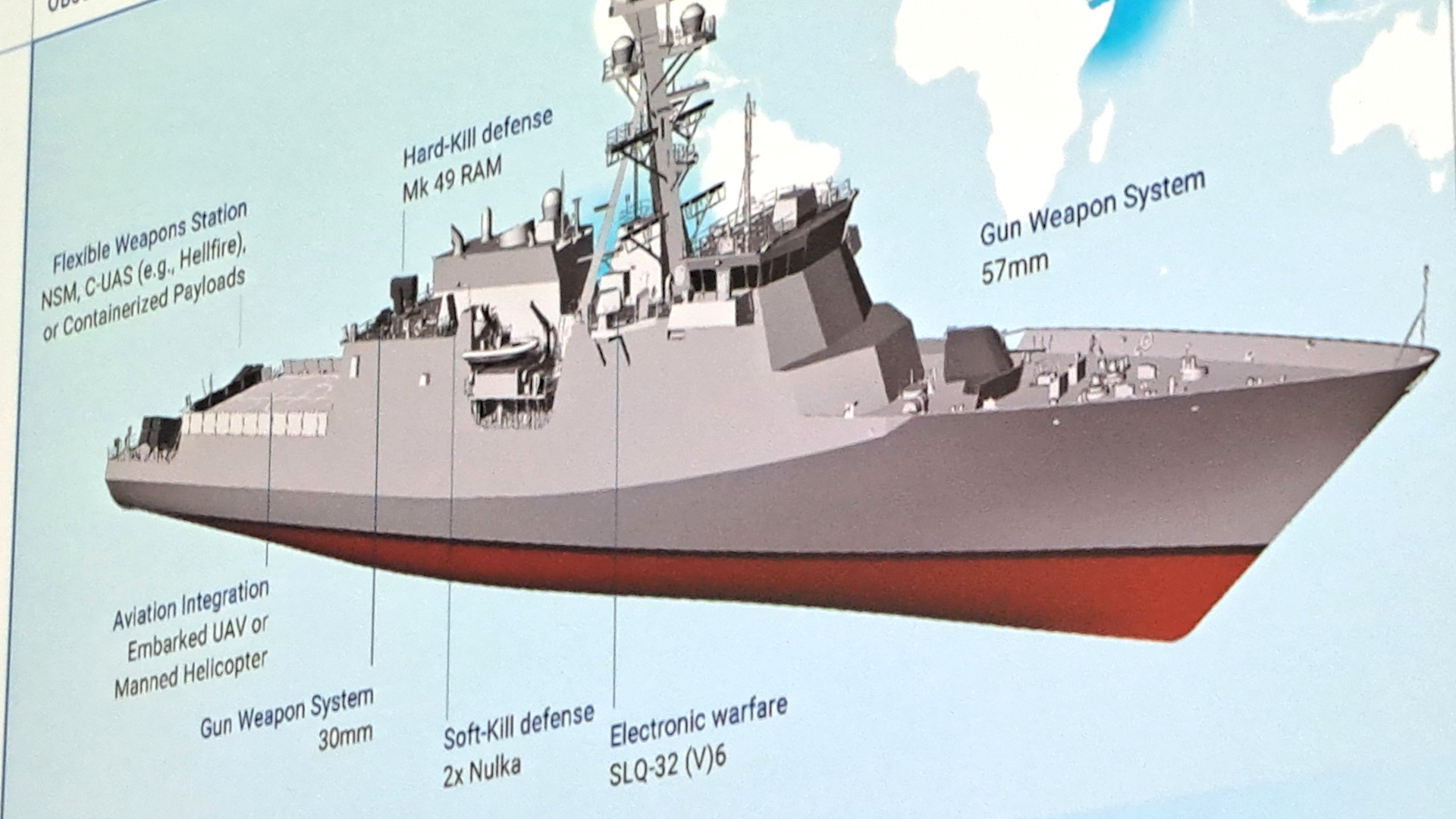

In terms of integrated capabilities, the ships will have a 57mm main gun in a turret on the bow, as well as a 30mm automatic cannon mounted on the rear of the main superstructure alongside a point defense launcher that will be loaded with up to 21 RIM-116 Rolling Airframe Missiles (RAM). They will also feature an AN/ALQ-32(V)6 Surface Electronic Warfare Improvement Program (SEWIP) Block II suite, launchers for expendable Nulka decoys, and an AN/SPS-77 Sea Giraffe medium-range multi-mode surveillance radar. There is a flight deck and hangars at the stern that will allow for the embarkation of helicopters and uncrewed aerial vehicles. The 30mm cannon, RAM launcher, and Sea Giraffe radar are not found on the Coast Guard’s NSCs, which also have an earlier variant of the SEWIP system. Both ships have a standard crew complement of 148.

The biggest difference between the NSC and the FF(X) is the Navy’s plans to use the fantails on the latter ships as a space for containerized weapon systems and other modular payloads.

“We are going to evolve it over time. Everybody keeps asking me, what about this? What about that?” NAVSEA’s Miller said. “You know, my answer back is, I care about getting this ship into production, [and then] learning, adapting, and figuring out what this ship needs to grow into.”

“The vision here is we will have capability in a box,” he added. “I think you all will agree that we have come a long ways in our ability to use shipping containers, and I am excited.”

The Navy says it is looking first at installing launchers for up to 16 Naval Strike Missiles (NSM), a stealthy anti-ship cruise missile with secondary land attack capability already, or as many as 48 AGM-114 Hellfire missiles. The Navy has also presented the Hellfire armament option as being focused on knocking down hostile drones, though they could be employed against other target sets. As noted, the NSC-based frigates will not have an integrated VLS array, at least initially.

“We developed these [FF(X) requirements based on what we thought we needed in a frigate,” Rear Adm. Derek Trinque, head of the Navy’s surface warfare division, or N96, also said while speaking alongside Miller and other members of a panel yesterday. “There was a lot of desire to put an awful lot of expensive capability into these ships. And that would have been cool, except that wasn’t really what we needed, because we have in the Flight III [Arleigh Burke class] destroyers coming down the ways right now, the large surface combatants that are appropriate for today.”

This is a pronounced shift in thinking from what led to Constellation class program, which explicitly sought a larger and more capable warship to make up for the shortcomings of the Navy’s two classes of LCSs.

The LCS program also notably focused heavily on modular capability packages, or modules, to help give those ships flexibility to perform different mission sets as required. In practice, the Navy has deployed LCSs with largely fixed configurations. More recently, the service has been looking to containerized weapon systems as a way to bolster the still-lacking firepower of those ships.

“I want to distinguish between LCS mission modules and containerized payloads. One of the challenges with LCS mission modules was we were taking systems that did not yet exist and marrying them with a ship that we were just starting to build,” Rear Adm. Trinque explained. For FF(X), “we are going to take existing systems and to all intents and purposes, put them in a box with an interface to the ship’s combat system. That will make this work, and it will allow [for] rapid switch out of capability, [and] rapid addition of capability.”

NAVSEA’s Miller also stressed the benefits containerized payloads would offer in terms of being able to “burn down risk.” A system that does not prove itself or is otherwise found not to meet the Navy’s needs could simply be unloaded from the ship and readily replaced with something else.

It is important to note here that the containerized payloads the Navy is eyeing for FF(X) could include more than just additional weapons. This modularity is seen, in particular, as a way to address the design’s current lack of a built-in sonar array (fixed and/or towed) and other anti-submarine warfare capabilities, which were expected to be another important feature of the Constellation class frigate. In 2022, the Navy also scrapped plans for an anti-submarine warfare missions module for its LCSs.

“We are not walking away from ASW [anti-submarine warfare] at all. We are all in on ASW,” Rear Adm. Joseph Cahill, Commander, Naval Surface Force Atlantic, another member of the panel at SNA yesterday, declared. At the same time, he put emphasis on the Navy’s workhorse Arleigh Burke class destroyers as the main warship for executing that mission, while also acknowledging how other assets, and not just at sea, could contribute to the anti-submarine fight.

Overall, the Navy has made no secret that its main goal with FF(X) is to get hulls in the water as quickly as possible to start helping make up for shortfalls now in its surface fleets. The hope is that this will also have a positive impact on the naval shipbuilding industry in the United States by jump-starting demand for work that could be spread across multiple yards, as you can read more about here. The service has expressed a clear willingness to trade capability, at least up front, to meet its aggressive timeline goals. The hope is that the first FF(X) will be in the water by 2028.

The schedule for the delivery of the future USS Constellation had slipped to 2029 at the earliest before that program was cancelled. The Navy had awarded the first contract for those ships in 2020. The Constellation class design was also based on a proven in-production frigate, the Franco-Italian Fregata Europea Multi-Missione (FREMM; European Multi-Mission Frigate in English). However, successive changes meant that it ultimately had just 15 percent in common with its European ‘parent.’

“This ship [FF(X)] is done being designed,” NAVSEA’s Miller said yesterday. “We are going to go through a very, very, very – like, on one hand – number of engineering changes to get it to be what we want.”

“This frigate is designed off of a proven blue water modern hull, [the] NSC. That hull is designed following Navy rules, standard structural ship design Navy rules for the Navy,” Rear Adm. Trinque also noted, in part to address separate questions about vulnerability and survivability in using a ship based on design intended for Coast Guard use. “It’s a very, very common rule set that we’re familiar with back to DDG-51 [the Arleigh Burke class destroyer]. That’s how that platform was designed. So, there’s commonality in the robustness of that design, and that’s something that we would leverage and depend on in looking towards the ability to address the vulnerability issue.”

There are still questions about whether the focus on containerized payloads will hamper the FF(X)’s operational utility, even as the Navy works to evolve the design. The missile options the Navy has presented so far are decidedly limited compared to the 32-cell Mk 41 VLS array that was a central requirement for the Constellation class, each of which would also have carried 16 NSMs. TWZ previously explored in detail earlier questions about whether that was even a sufficient number of VLS cells for that ship to perform its expected missions. On top of this, the Navy is looking at major losses in total VLS capacity in its surface and submarine fleets with the impending retirement of the last of the Ticonderoga class cruisers and its four Ohio class guided missile submarines toward the end of the decade.

Though containerized payloads do offer flexibility, any ship can only be configured in one way at a time, on top of only being able to be in a single place at once. As an example, the Navy would not be able to readily re-task an FF(X) at sea and loaded for the surface strike mission to go hunt submarines. The service does see the frigates being deployed as part of larger surface action groups, which would have the benefit of a wider array of capabilities spread across multiple types.

“If one of those things is something that we need to get into the design of the ship [FF(X)], [it] is something that we will go consider,” NAVSEA’s Miller did add yesterday. “We will figure out what has to be done, but we’ll do it in a smart, controlled way. I am trying to control the appetite.”

Integrating a VLS and other capabilities into the existing FF(X) design is certainly a possibility in the future, but it could be a complex and costly proposition if the design is not configured to accommodate those additional features to begin with. The Navy will likely look to build more substantially modified versions of the ship in future ‘flights’ down the line, as it has done with some other classes. Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII), which designed the NSC and is now working on FF(X), has done work in the past on other design concepts in this general family that have VLS arrays, as well as expanded suites of sensors and other systems, as seen in the video below.

The Navy is also planning to further bolster the FF(X)’s built-in capabilities by deploying them as motherships for future fleets of uncrewed surface vessels, likely offering a distributed arsenal, as well as additional sensors. As TWZ previously wrote:

“In this way, an FF(X) could still call upon a deeper and more flexible array of weapon options without having to have a VLS integrated directly onto the ship. The uncrewed platforms would also be able to operate across a much broader area than any single crewed frigate and present a different risk calculus for operating in higher-risk environments. All of this would expand the overall reach of the combined force and present targeting challenges for opponents. But there are also substantial development and operational risks with this kind of arrangement. As it sits, this kind of autonomous vessel and manned vessel teaming is still in development. Operationally, leaving the ship without, or with very limited, area defense capability is at odds with many future threat scenarios.”

This last point underscores some of the biggest still unanswered questions about FF(X). There does not appear to be any explicit talk so far about options for expanding the frigate’s anti-air arsenal beyond its integrated point defense capabilities and add-on counter-drone interceptors. BAE Systems has been working on a Next Generation Evolved Sea Sparrow Missile Launch System (NGELS) based on its modular Adaptable Deck Launching System (ADL) for the U.S. Navy and American allies. Around SNA, the company also put out a computer-generated video showing a containerized launcher firing a surface-to-air missile from an uncrewed surface vessel. There could be other options, but it is unclear how many Evolved Sea Sparrow Missiles or other longer-range SAMs in total could be loaded on the FF(X)’s fantail. The ship’s sensor suite may limit just how many aerial targets can be engaged rapidly and what type, as well. A lack of radar illuminators would prevent the use of some legacy anti-air missiles.

The lack of any real anti-air warfare and area defense capability is one of the biggest criticisms leveled at the Navy’s existing LCS fleets, and that imposes limitations on their ability to conduct more independent operations. Anti-air and anti-submarine warfare capabilities would be very relevant, if not critical, for the kinds of missions one would expect to assign to a frigate in a future major conflict, such as convoy escort.

Overall, despite its clear hope that the FF(X)s will eventually take on many roles in a variety of operational contexts, there are signs already that the Navy is looking at a relatively limited mission set for these ships to start, and one that aligns more with how it is employing its LCSs today.

“In 1995, I did counter-drug ops in my first ship, [the Ticonderoga class cruiser] USS Philippine Sea. Using a guided missile cruiser, or nowadays a guided missile destroyer, for counter-narcotics ops is a choice I don’t want the fleet commander to have to go through,” Rear Adm. Trinque said during the panel at SNA. “So there are great photos of [the Arleigh Burke class destroyer] USS Sampson having successfully completed counter narcotics ops in the Eastern Pacific recently, and I think that puts Vice Adm. [John F. G.] Wade [commander of the Eastern Pacific-facing U.S. Third Fleet] in a bad position.”

Adding more blue water hulls to the Navy’s surface fleets would certainly be a boon and offer valuable capacity to help free up larger warships for missions that are more in need of their capabilities, but this will require ships that can perform useful missions. At the moment, the Navy is betting big on the ability to swap out containerized payloads to give FF(X) what it will need to have a meaningful impact.

Eric Tegler contributed to this story.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com