Operation Desert Storm began 35 years ago last week on January 16, 1991. It was five months after the Iraqi military invaded and annexed its southern neighbor, Kuwait. Within days of the invasion, the United States and partner nations began to deploy assets into the Middle East to protect countries like Saudi Arabia and others from further aggression. This included sending in RF-4C tactical reconnaissance Phantoms, and one crew, in particular, flew a mission on this day 35 years ago that was uniquely harrowing and important — so much so that they were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for their efforts.

This is their story.

Spinning up

While fighters like the F-15 and F-16 quickly deployed to secure the skies over Saudi Arabia and the region under Operation Desert Shield, military commanders were in desperate need of timely intelligence. They needed to know about the troop and aircraft movements of the Iraqi Army and Air Force along the vast Saudi-Iraq border, as well as in Kuwait.

With an immediate need for tactical reconnaissance assets, six RF-4Cs from the 106th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron (TRS) of the Alabama Air National Guard took off from Birmingham, Alabama, on August 24, 1990. It was a nearly 16-hour flight to Al Dhafra Air Base in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The flight covered 8,000 nautical miles and required 16 air refuelings.

The USAF RF-4C was nearing the end of its service life in 1990. Developed in 1962 with a total of 499 being built, it was equipped with an elongated nose that carried up to three separate camera systems. It would be the last dedicated tactical reconnaissance aircraft in the USAF, and Operation Desert Storm would be its final fight.

The 106th TRS was chosen because it was equipped with a new camera system, the KS-127A LOROP (Long Range Oblique Photography). LOROP, originally developed for the RB-57F, was capable of astonishingly high-resolution images of objects 100 miles away. The new KS-127A version was able to fit in the nose of the RF-4 instead of in a large pod underneath the centerline of the jet. The squadron had two aircraft equipped with the new system, and the other four aircraft also had a new navigation system. It was called the Navigation and Weapons Delivery System (NWDS) and was a far superior navigation system compared to previous ones, which would be important when flying over vast desert terrain.

Soon after landing in the UAE, the 106th was flying operational reconnaissance missions on behalf of U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM). Most of the missions fell under the ‘Eager Light’ designation. These missions consisted of RF-4s flying along the Saudi and Kuwait border, taking imagery of Iraq’s air defense systems and other potential targets.

On October 8, 1990, the 106th lost an RF-4 in a low-level training mishap in the UAE. The loss of the aircraft, as well as other issues within the squadron, resulted in the decision to pull the 106th from the theater and send another Guard squadron to take over the Eager Light missions. The ‘High Rollers’ of the Nevada ANG were chosen to replace 106th because they had some of the most experienced pilots and their aircraft all had updated Radar Warning Receiver (RWR) gear and Electronic Countermeasures (ECM) pods. With the decision made, the Reno-based 192nd TRS quickly formed a detachment of aircraft and 125 personnel to deploy. They sent only four aircraft because they would use the two aircraft from the 106th, which were already in-theater, and had the new LOROP cameras.

The 192nd had been flying the RF-4C since 1975 and was a highly decorated unit that received numerous awards for their reconnaissance skills.

In December of 1990, the 192nd deployed to Sheik Isa Air Base in Bahrain. This airbase also hosted other USAF F-4s, including the F-4G Wild Weasels, as well as several USMC squadrons. The squadron was assigned to the 35th Tactical Fighter Wing, which also included active-duty RF-4Cs from the 12th TRS at Bergstrom AFB, Texas. Immediately, the 192nd sent personnel to the UAE to start the transition with the 106th. Having been in theater for several months, the 106th provided valuable insight on how to operate in this new environment, including how to fly as part of large strike packages.

Unlike most USAF squadrons, the 192nd included a large number of airmen whose job was to process film from flights, as well as intelligence analysts who could quickly identify targets and provide bomb damage assessments (BDA). The squadron deployed with a Portable Photography and Interpretation Facility (PPIF) to immediately process and review the photos.

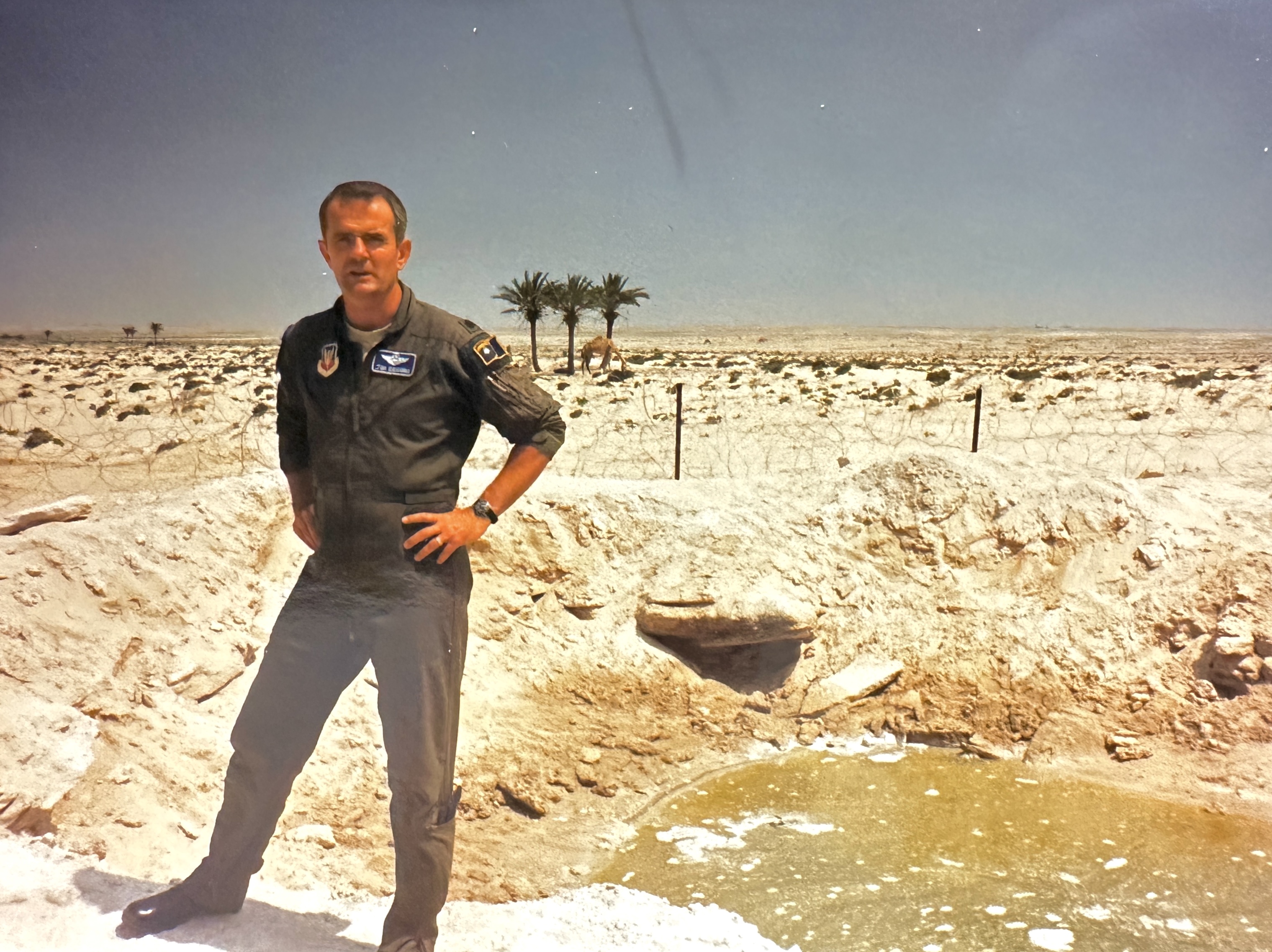

Leading up to hostilities, the pilots of the 192nd flew a host of different training and reconnaissance missions. Pilot Lt. Col. Jim Gibbons and Weapon Systems Officer (WSO) Maj. John Fuller teamed up for several sorties during both Desert Shield and Desert Storm.

Gibbons was a veteran combat pilot and flew A-37s in the 1st Special Operations Wing in Vietnam. He flew from several classified locations during the war and later transitioned to the RF-4. Fuller was an enlisted technician in the Air Force, but when he heard his unit was getting the RF-4, he applied and was accepted into flight school. Fuller became an expert in electronic warfare and radar systems.

Talking about deploying, Fuller explained, “We landed in Bahrain on a C-5 and then got on a C-130 to Al Dhafra Air Base in the UAE. We started learning the procedures and what to do in the area. It was go, go, go. We went over with 125 people, 23 of whom were aircrew flying six aircraft. The active guys from Bergstrom AFB in Texas had close to 1,000 people and 12 aircraft. Many days, the active guys couldn’t get an aircraft flyable, so Jim and I sometimes had to fly two missions in a day. Those were 20-hour days. We had such a high mission capability rate because our maintainers had an average of over 18 years of service. That was the key, because the active-duty guys could not come close.”

Fuller elaborated, telling us, “When we started flying, we had to draw all of these maps up. We had to learn where all of the air refueling tracks were and how things were organized. It was very busy work. We got in about 10 missions before the war kicked off. The weather was great before the war, but as soon as the war started, the weather turned very bad. We had only two aircraft with the new camera system that could really look deep into enemy territory, and we were also using our other sensors on the aircraft. Initially, we were trying to see what was coming into the forward edge of the battlespace. We started to see they were bringing in all these oil lines and digging ditches to create a fire. We were able to see all of this activity, but during the war, we started to do deep interdiction missions where we were looking farther into the second and third echelon, so we could see what was coming down toward the battle area.”

As a WSO, Fuller had his hands full in the back seat. He was responsible for the electronic countermeasures, the cameras, and the radar. The WSO also needed in-depth knowledge of the radar warning receiver, which was important for determining the threats the aircraft faced and the tactics to defeat them.

“I called the pilots glorified taxi drivers because I had a lot of work in the back. Every enemy radar had its own individual characteristics and made different sounds in your headset. I didn’t have to look at the machine to tell; I could hear it. I also had to operate our three cameras, know which programs to run and which camera settings were needed, and monitor fuel while completing checklists. In all seriousness, we respected the pilots greatly for their knowledge and flight skills that kept you alive and out of trouble,” Fuller described.

In the United States, military aircraft operated on UHF radio frequencies. In the desert, they were using VHF, which the RF-4 lacked. To come up with a quick fix, maintainers removed some screws from the canopy to install an antenna with wires running to a box mounted on the instrument panel. Only the pilot could talk on VHF, but the WSO was still responsible for changing frequencies, which made things difficult.

Fuller added, “Every back seater had to load the codes you were operating with. Also, every 30 minutes, we had to change out Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) so we would not get shot down by our own people. We had to change our radio frequencies about 20 to 30 times on a single mission. You might be working with a Saudi AWACS one day and an American one the next day. With over 3,000 missions in a day, that was a lot of air traffic.”

“One day, I can remember we had to hit the tanker, so we went up to it, and I called out to the pilot that it was the wrong one. He asked me how I knew, and I told him that it was because the tanker was using the basket, which was for the Navy and Marines. We had to go find our tanker. The back seater had to really keep up and be in front of the pilot, if you will, because he had the threats on his map, and we would brief that. If we had something that interfered with our planned routing and we had to get off our planned heading because of it, you had to get back on course before you hit the target or the Initial Point (IP), because you always had threats on your targets, so you had to deal with that.”

After every mission, Fuller would write down lessons learned from that mission. It was his way of improving after every flight and of sharing knowledge with the other crews.

On his first mission since arriving in the theater, Fuller wrote about how hard it was to navigate across the great desert expanses of the Arabian Peninsula:

15 DEC 1990

Yesterday was my first flight in the jet since I arrived. The view of the sand was as far as I could see and then some. We flew in one area, somewhere between 80 and 100 nautical miles, where the terrain was flat, with no risers of any kind. There wasn’t any kind of vegetation. It was flat. It reminded me of flying over the ocean. No matter which direction you looked, all you could see was more sand and the curvature of the earth. I had my radar on, but there were no returns. I was on a 20-mile scope when I came up on 17 circles being displayed. The reason these fields had shown up was that the fence gathered windblown sand, which returned on the radar scope. One of the things that truly amazed me was the number of tire tracks in the sand without seeing anyone. Our next terrain feature brought us into an area of sand dunes, which were approximately 1,000 feet in elevation and red in color, with dry lakes over a half mile wide. One could not use their radar to navigate in this area because the sand dunes have poor returns. Trying to fly under the radar would be very difficult. The only way to navigate would be with an NWDS aircraft. The old steam-driven INSs (Inertial Navigation Systems) would get you in the area, but with limited accuracy. The maps are useless because there’s nothing to look at.

Oops! We Are In Iraq

Of the 10 or so flights Gibbons and Fuller had during Desert Shield, one was more memorable because they inadvertently entered Iraqi airspace. Fuller explained, “About two weeks before the war, we were flying along the border with all of the points in our INS. On that particular day, the wind was the opposite of what it normally was. Normally the winds were from the northwest but instead they were coming from the south, and so the winds shoved the aircraft north over the border into Iraq. I looked down and told Jim, “Well, we just crossed into Iraq.” Jim asked me how I knew that, and I said, “Because I can see the fence line and the tail of the needle was pointing behind us.”

The Iraqi air defenses activated their SA-2 radars and began tracking the intruding RF-4.

Gibbons added, “We were looking for radar and Scud sites. When we drifted across the border, it got exciting. Fuller was busy working the equipment when the AWACS came over the radio to tell them there were SA-2 missile sites over the border and suggested we come south. We didn’t have the radar that the F-4Gs had to pick up a signal and plot it. We had to guess for the most part.”

Fuller summed it up, “We did a teardrop maneuver, and I was able to do some triangulations, and I was able to get some fixes as we worked our way back. They were given to the intel guys for later on when hostilities started.”

For most of the Desert Storm missions, the RF-4Cs flew with an AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missile for self-defense. Higher-ups decided that during the war, RF-4Cs would not carry missiles to prevent a blue-on-blue incident, since the aircraft lacked an air-to-air radar. But a quote from a general would tell a different story.

Fuller wrote in his logbook:

Special entry

Today, we were met by the Great Burning Bush (A USAF general). He was an arrogant prick. His answer for the reason why we weren’t carrying missiles was “I don’t want Goddamn Recce trying to shove a missile up a MiG’s ass. Your job is to take pictures and return home.”

What an ……..!

Wartime

A day after the war started, Gibbons and Fuller got their first tasking. They were to fly north and photograph bed-down bases, which were where Hussein scattered some of his fighter aircraft after B-52s struck many of the larger airfields. Iraq had 24 main operating bases and 30 dispersal fields at the time of the war. Going in at 30,000 feet, 4,000 feet above them, were four F-15Cs, and above that, two F/A-18s as part of the package. They were in heavy clouds, and it was really bad because they could not see their wingman. While on this mission, they did not get any film of the targets, but they were able to collect data from the radar warning receivers to show the location of the search radars.

Fuller stated, “During the war, we learned to brief things much more quickly because we did not have the time when the war started. We already knew a lot, like procedures, NOTAMS, and which other bases you could land at in an emergency.”

The first mission lasted 2.1 hours. Fuller’s notes read:

18 Jan 91 THE WAR STARTED ON JAN 17.

Today’s mission was a walk in the park. It was another classified mission of 2.1 hours at Jalibah Airfield. The weather was dogshit. We had many RWR indications of SAMs, but they would not stay up long enough for the Weasels to shoot them with their HARMS. A nice little creation used to kill radar sites. Our package included four F-15s, two F-18s, and two RF-4Cs. We pressed into the area.

Lessons learned:

Get a good TOD (time of day) with AWACS so all fighters are on the same TOD. If someone shuts down an airplane and leaves the NWDS on, the NWDS will not work when power is applied to the aircraft before you get into the aircraft. If you go into bad guy territory, ensure that you have a map with heading in case NWDS dumps. Just because the ATO (Air Tasking Order) states that one must be within 10 nautical miles of an exit point doesn’t mean you have to fly over that point if it is marked with threats. STUPID STUPID STUPID. I can’t say enough about our maintenance folks. They prepare our jets with their hearts. I’m very proud of them.

Bandit 12 O’clock

On January 21, 1991, Gibbons and Fuller would be the 2nd aircraft in a two-ship formation. It was a 2.5-hour mission that required one aerial refueling. Gibbons said, “This was one of those days where we were bait for the Wild Weasels. We were leading them back and hit the tanker, and then squeezed between a few thunderstorm cells along the border. The whole mission was done in radio silence, and we were to head up near Baghdad. Because we were the second two ship, I was following the lead aircraft. I assumed that he meant the rest of the strike package was behind us, but that turned out not to be the case. Apparently, the gap that we flew in closed very quickly, so none of the other aircraft made it through. We pressed north, unaware that we were by ourselves.”

Soon after entering Iraqi airspace, Fuller heard the AWACS aircraft tell them to immediately head south. It went something like this:

“PINE 72, Bandit at your 12 o’clock 4o miles out. Suggest you work south.”

Gibbons assumed the lead aircraft heard the instructions from the AWACS, but the lead aircraft continued to press northbound.

An Iraqi MiG-29 was heading toward them. The AWACS was about 40 missiles south of the two RF-4s. The AWACS flew with a fighter escort, but when they picked up the MiG-29, the F-15s providing escort were heading to a tanker about 70 miles away to refuel. The RWR gear on the RF-4 told Fuller it was a pulse-doppler radar tracking them. Iraqi MiG-29 pilots would silence their radar once they found a target.

Fuller explained, “Once the MiG-29 found a target, they would turn the radar off and use their infrared within a certain range to find the heat signature, then pickle a missile. The next call from the AWACS was that the MiG was 25 miles away and closing. Our lead wanted one more look, but we forced the lead aircraft into a turn. Gibbons pushed the throttles up and went around the lead before separating. Another call from AWACS stated 15 miles and in pursuit. It seemed that the lead aircraft did not want to use the afterburner for a rapid egress. We kept coming out of afterburner because the lead didn’t seem like he was in a hurry for whatever reason. The bandit came within 12 nautical miles before returning north. That was good because we were left hanging because leadership had taken away our AIM-9 missiles, so we had no option to fight back.”

Gibbons added, “I did an F pole maneuver.”

The F-Pole maneuver is a Beyond Visual Range (BVR) air combat tactic, primarily for semi-active radar homing (SARH) missiles, focused on maximizing the slant range (F-Pole) at missile impact by making the enemy missile fly a longer, curved path to intercept, ideally forcing it to run out of energy or lose radar lock before hitting you.

He added, “After the maneuver, we were supersonic at about Mach 1.2. Then I got a call from AWACS.”

“PINE 72, OPEC 50 flight of four F-15s heading your way at 50,000 feet and Mach 2. They will be there in 10 minutes.”

I said to myself, “They are going to be late to the show.”

It was said that the MiG-29 flew supersonic to Iran rather than get shot down by the approaching F-15s.

Gibbons and Fuller were flying back to base with Fuller doing his paperwork on the flight south to the Sheik Isa Air Base. Once they hit the runway, Fuller began removing his leg garters. When they entered the revetment and opened the canopy, a crew chief set up the ladder on the aircraft. When the chief pinned the ejection seat to make it safe, Fuller stated:

“I said, ‘Get out of my way’ and he knew I was pissed. Gibbons yelled at me from the cockpit, but he was still in his garters. He yelled, ‘If you hit him [the flight lead], you are going to get courtmartialed,’ but I didn’t give a damn because he almost made my wife a widow. I ran toward my wingman’s aircraft, but Gibbons caught up to me and pinned me down.”

A later discussion between the two crews revealed that the lead aircraft was not receiving radio transmissions from the AWACS.

Fuller’s notes from this mission read:

21 JAN 91

Today’s mission was classified. Jim and I had a wonderful time. Exciting, and I don’t want to do that again. Chinnock and Snyder are our leads. We were number two. We air refueled. Flying time was 2.5 hours.

Lessons learned:

When AWACS gives an order to work south, head south.

1.) Never stick your nose where it doesn’t belong. Don’t wait for the package at the push point. Stay with the package on the tanker and depart as one unit.

2.) Don’t go anywhere without having an escort.

3.) If it weren’t for AWACS, my pilot and I would have not made it. We were left without any situational awareness. Bad guys cross the imaginary line called the boundary between countries.

4.) When you are at home, train the way you’re going to fight. Don’t conserve fuel when doing air-to-air work to have another engagement. Don’t use full power when the burner is needed. Don’t be complacent. The scud attacks are denying us sleep. I wish they would stop it. Now I know how the Brits felt during World War II.

The Big Mission

In a desperate attempt to sway public opinion against the U.S. and coalition forces, Saddam Hussein ordered his troops to open oil manifolds in Kuwait to make it appear that the U.S. caused it through bombing. The result was the release of thousands of gallons of oil into the Persian Gulf. It was quickly becoming an environmental disaster.

On January 26, 1991, a priority mission came down to acquire the exact locations of the oil pumps. It was a sortie that came down with the highest urgency and needed to be done the next day. The mission was to take pictures of the open oil manifolds to prove to the world that they were intentionally opened and not bombed as Hussein had claimed. This mission would also help targeters find the right place to drop bombs so that the oil flow would stop.

A colonel from headquarters in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, came to Bahrain. He reviewed all the flyers records in the squadron and chose his two crews. The crews had to sign for the mission and agree that they were not allowed to discuss the mission for 20 years after the war had ended.

Gibbons and the three others took the mission, and the whole afternoon, they were planning. They were reviewing the maps and available intel.

They walked through the whole mission, from where they would meet the tanker to where they would set up their Initial Point (IP). They drilled down on what they were after and where they needed to be at a certain time.

On January 27, 1991, only 10 days after the war between Iraq and the Allied Coalition Forces began, Gibbons and Fuller took off with the other crew on a mission that would result in them being awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Equipped with LOROP special cameras that provide highly detailed photographs from long distances, the two RF-4 aircraft took off from Sheik Isa Air Base, Bahrain. They would fly without fighter support, relying only on their speed and the skills of both as pilots and WSOs.

Gibbons explained further:

“We took off and immediately hit a tanker, so we had the right amount of fuel. During our pre-mission planning, we intended to go from the initial IP, which was south of the target area, all the way up to Kuwait, where the refinery was. Fuller calculated it for 600 knots, and the weather deck was around 3,100 feet, so I planned to be at 3,000 feet and about 1 mile offshore, which would keep us out of small-arms range.”

When Gibbons hit the IP, he kicked his wingman off to his right side and continued heading north. Fuller called ‘HACK’ at the IP, which made both of them push their clocks so they could stay in sync. Holding 600 knots, Gibbons noticed a tremendous amount of AAA coming off the beach.

Gibbons said, “Every flash of light you see is a gun pointed at you. You could see the tracers coming up at you; they are 37mm, about the size of a golf ball. As they come up, I push a little forward on the stick and watch the AAA go over the top of us, and when the next stream comes up to us, I either go down or up. I’m doing this yo-yo effect as we fly at 480 knots. Fuller says ‘five seconds’ as he turns on the cameras. The next call I was waiting to hear was ‘Target acquired,’ but it never came. Instead, the next call from Fuller was that the camera stopped working.”

With the camera inoperable, Gibbons rocked his wings so his wingman could form up as they made a hard right turn and headed southbound to 14,000 feet. As they began to head south, Fuller informed his pilot that the camera was working once again.

Gibbons told us, “With the camera working, I asked John if he wanted to go back, and John said, ‘I sit three feet behind you, Jim, where you go, I go. The funny thing is, when we got back on the ground, I thought John meant yes, but he told me it was okay if I didn’t want to go back and that we could regroup and do this another time. Thinking John wanted another go, I told him to calculate the IP to target at 600 knots this time, since they know we are coming and have had practice shooting at us.”

At 600 knots, the aircraft was at full power without using afterburner. While Fuller was doing all of the calculations, Gibbons was looking out of the cockpit and realized the conditions had worsened.

“I said to myself, ‘Oh my god,’ because I realized with the smoke and weather that we would have to be lower and closer to the shore in order to have a clearer vision of the objective. Fuller put the IP into the navigation system, so I pushed the throttle up, and we headed in again.”

“We ‘Hacked’ the clock once again, but this time we had AAA coming at us from every direction. This time around, I was trying to hold still because I thought the camera was sensitive to jiggling and would shut off. Coming in, I had to get even lower and closer because of the weather and smoke. I could not keep it steady because I had to dodge the AAA. Fuller asked me to keep it steady, but I told him, ‘I’m only trying to keep us alive.’”

Looking back at the second attempt, Gibbons realized they were now over the beach at under 1,000 feet, instead of a mile offshore as originally planned. They were both nervous that the camera would ‘go horizontal’ and stop working again.

With cameras on and seemingly working properly, Gibbons went into afterburner after Fuller called to say they were being tracked by an SA-2 surface-to-air missile. He pulled a hard right turn into the smoke and clouds.

The maneuver enabled the electronic countermeasures pod underneath the RF-4 to look directly at the threat. During all of these missions, the aircraft flew with the ALQ-131 pod for radar jamming and self-protection.

Gibbons explained:

“In the clouds and smoke, I saw a glow behind me over the cockpit which made it look like the back of our airplane was on fire. I wasn’t looking in the rear-view mirror because, at 100 feet and 620 knots, I was concentrating hard not to crash into the water. While I am looking down at the water, I see guys in little boats shooting at the aircraft. I took the aircraft out of afterburner and set it to idle, but it was still pulling about 6Gs.”

“We started to slow down when John asked why. I replied that I could not ask him to eject at 600 knots because that would kill us. I thought the glow was from being on fire from either the AAA or the missile. John asked me why we would eject, and just as I was about to explain it to him when I looked into the rear mirror and saw the glow was from John ejecting flares. When I realized what was happening, I laughed for a second, then went right back into the afterburner, pulled 9Gs, and started a climb to join my wingman.”

On that second pass, the aircraft had so many symbols on its radar warning receiver gear, and it generated so much heat and power, that the system actually overheated and went blank in the middle of the run.

Heading south with the mission complete, the two RF-4s landed at the airbase, and the imagery was immediately brought in for processing. They quickly realized they had the imagery they needed. The photos were sent to CENTCOM, which then shared the imagery with various news outlets to prove to the world that it was indeed Saddam Hussein who was leaking massive amounts of oil into the Persian Gulf.

Speaking about the other crew, Fuller stated:

“Our wingmen, Lt. Col. Chuck Chinnock, and Col. Woody Clark did a terrific job keeping us aware of our threats. In pilot language it is called situational awareness. When we were in the dense smoke, we did not see them, I called out for them to maintain their altitude, heading, and airspeed. We needed to maintain our separation. I know they took a lot of the AAA and Radar Guided and IR missiles off us because of their use of chaff, flares, and ECM. Never once were they lagging behind. They were right there in position to protect us of oncoming threats. Thanks, guys.”

For the mission, all four members of the aircrew were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in March of 1992. The DFC is the fourth-highest award for heroism and the highest award for extraordinary aerial achievement.

John Fuller’s DFC citation reads:

Major John C. Fuller distinguished himself by extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight as an RF-4C weapons systems operator in the Kuwaiti theater of operations on January 27, 1991. On that date, Major Fuller was a member of a specifically tasked reconnaissance mission to acquire politically sensitive, priority imagery of enemy targets in Kuwait. Approaching the target area, the flight was immediately engaged by enemy AAA and surface-to-air missiles. Despite heavy enemy defenses and low visibility, Major Fuller acted quickly to defeat the threat and obtained aerial reconnaissance and intelligence, which proved vital to the United States’ national posture. The professional competence, aerial skill, and devotion to duty displayed by Major Fuller reflect great credit upon himself and the United States Air Force.

Fuller’s logbook reads:

27 JAN 91

Today’s mission was another classified one. Up into a burning hell with oil on fire everywhere. I have seen some large oil fires and pictures of them, but this one takes the cake. The mission was planned at 8000 MSL, an 8-mile standoff. The weather in the target area was 2300 feet solid overcast, with smoke and haze. The visibility was approximately 1 1/2 miles. We really tried hard to meet our targets. The check was complete, pods on, chaff doors were open and blazing at the speed of heat. The coastline was not visible on our planned route. So, Jim turned toward the shoreline. While I was aiming the sides on the camera, checking out wingman’s six, and listening to all our RWR, someone would try to lock us up. After about 1/3 of our photo run, our cameras shut down, so we turned east to come back and try again.

We passed our burning oil platforms, a burning ship, and saw some coastal patrol boats. The coastline had let up from gunners trying to shoot us down. We traveled south and got back on our flight pass again. It was the same thing, except the camera was working again, and we were closer than before. This time I could see the streets between the buildings. The city once looked beautiful. I picked up a bogey at our left, seven crossing to our right, and then we had two of the 12th AF recce birds meet us head-on. Our closure speed was somewhere around 1200 knots beak to beak.

We pressed up on the coast and passed our target off to the left through the smoke and haze. A SA-2 TTR locked us up, not our wingman. I popped chaff and flares, and our wingman started popping chaff and flares. When Jim knew what was going on, he popped some more while we were outbound. We were able to break a lock on the SAM and proceeded on our way home.

Flying time 2.0

Lessons learned:

Use the right camera for the right job. Don’t try to fly under the weather or the gun; have your altitude and the fuses set accordingly. Our mission went very well. All of our film was totally unusable due to the weather and the camera’s cycling rate. It was discouraging to try so hard and not get any results. I wish the commanders would listen to me about which cameras to use. Two wasted sorties in harm’s way.

Though the first run into the target yielded no good imagery, the second pass proved much more successful. Within a few hours, four F-111s flew over the same area and precisely dropped several bombs that destroyed the oil manifold, stopping the oil from flowing into the Gulf.

The Great Scud Hunt

During the planning for the war with Iraq, it was assumed that Saddam Hussein would attempt to launch his Scud missiles at Israel in an attempt to break up the coalition by getting Israel to retaliate. On the first day of the war, over 150 missions were flown against fixed Scud launch facilities as well as support facilities. The Scud was a Soviet-designed, mobile, short-range ballistic missile (SRBM). It was capable of carrying conventional, nuclear, chemical, or biological warheads and was not very accurate.

On the second day of the war, the Iraqi military launched seven Scud missiles at Israel, hitting targets in Tel Aviv and Haifa. Although the missiles only caused minor injuries, military planners began to feel the pressure to devote more sorties to targeting mobile Scud launchers. When one Scud hit a residential section in Tel Aviv on January 22, killing three Israelis and injuring dozens more, the problem took on even greater urgency.

Gen. Charles “Chuck” Horner, commander of coalition air forces, immediately ordered a considerable segment of the available intelligence-gathering capability to shift to counter-Scud operations, including reconnaissance aircraft (U-2/TR-1s and RF-4Cs). The Central Intelligence Agency originally estimated that Iraq had about 30 mobile Scud launchers, so the hunt was on to find and destroy them.

Gibbons told us, “We started to get missions that took us into the western part of Iraq near Syria, looking for mobile Scud missiles. We flew around airfields known as H-1, H-2, and H-3. We would be assigned to search on highways in and around these airfields. The airports were bombed in the early days, but the area around them was known to be an operating area. We flew at about 10,000 feet, giving the cameras a broader coverage area. The highways were dangerous because you had AAA guns running up and down them. We would look for erosion features known as wadis, where there are small bridges that the launchers would like to hide under. Once in a while, we would see the truck’s nose sticking out because it could not fit under the bridge.”

The missions were long because the search areas were about 900 miles from the RF-4’s home airbase, so multiple aerial refuelings were involved.

On February 26,1991, Gibbons and Fuller flew one of their longest missions in the war.

Fuller’s notes read:

26 FEB 91

Today’s mission was another classified operation into the northwestern part of Iraq along the Syrian-Jordanian border. Flying time was 5.2 hours. Three AARS and a total fuel consumption of 46,000 pounds each. Target areas included H1, H2, H3, and numerous other targets, as well as Scud strip searches. We ended up 60 nautical miles north west of Baghdad. We were in the target area for 74 minutes. Our total mileage for the trip exceeded 2100 nautical miles. Four out of 16 targets were weathered out. Our mission was very, very successful. The photos were outstanding. Two hours into our flight, our NWDS started doing its own thinking, not what I had programmed.

Lessons learned

When using the destination table, you cannot program a destination point. Don’t make the mistake of having a memory lapse on the chaff-and-flare switch.

Enough said.

One night, Fuller was on desk duty when the base was notified of an incoming Scud missile attack. Fuller ran over to the intel shop and asked for the coordinates of where the missile was launched. The U.S. military had satellites that could detect launch areas. Fuller went to it, plugged the coordinates into his computer, and ran it out to where it was launched from. He printed up a copy, went to the command post, and walked into the morning briefing, which was full of people. His commander asked him why he was at the meeting, and he told him that he had the coordinates from where the missile had just launched.

Fuller explained, “A general asked what I had with me, and I told him. He kicked people out, and I told him how I got the information. He picked up the red phone to Riyadh and asked them what the hell they were doing. He said ‘I got a guy here from reconnaissance who went and got these coordinates. I want an F-15 to go and blow these guys up.’”

Even on the ground, Fuller was helping with the Scud hunt.

The aircrews endured 36 Scud attacks, sometimes two or three in a night, so sleep became an issue, which was affecting the crew. One night, Fuller recalled, “a missile got close, but a Patriot intercepted it. You hear three loud booms. The guy who ran the Patriot site was called Saint Patriot. When he came into the chow hall after that attack for breakfast, he received a standing ovation.”

Ceasefire

On February 28, 1991, just 100 hours after the start of the ground offensive to liberate Kuwait from Iraqi occupation, a ceasefire was declared by President George Bush.

With the war over, the squadron continued to fly missions into Iraq and Kuwait to assess damage and make sure Iraq was complying with the ceasefire.

Fuller’s notes:

Today’s mission was another classified mission into Iraq. The ceasefire was announced this morning by President Bush, but we were tasked anyway. So off we went into bad guy land again, but this time without Weasel support. Flying time was 2.1 hours. The weather was great today. Recce was the only aircraft flying, and the MIG cap was up to protect AWACS. There is a quote about Recces: “We are the first in, we are there during, and we are there after. We are the last to leave. We are alone, unarmed, and unafraid.”

Lessons learned

I have found out that there are a lot of generals who are real jerks and have no business making the decisions they do. The Burning Bush is a classic example of stupidity at its best: not having an escort. We feel we are being used as bait for Saddam’s fighters to come up, so these F-15 pilots can become an ace. They need five kills to be an ace. In the meantime, it’s business as usual.

Coming Home

With a historic wartime deployment under their belts, it was time for Gibbons, Fuller, and the dozens of other members of the 192nd TRW to return home. Unlike Gibbon’s last war in Vietnam, this time he would be greeted with cheers and parades from proud Americans.

Because they flew the most missions in the squadron, the commander assigned Gibbons and Fuller to fly one of the jets back to Reno, Nevada. On April 4, 1991, they began the long journey home as a six-ship fleet of RF-4s.

Fuller recalled, “When we took off, we had to go south and then cross over to the Red Sea and come back up. We went over Egypt and into the Mediterranean. We landed in Zaragoza, Spain, and were met by the firetrucks that hosed off all of the soot and dust on our airplanes.”

The next day, the six aircraft flew all the way to Terre Haute, Indiana, to the National Guard base.

“It was very exciting. They handed us beers, and we had a police escort everywhere we went. We were welcomed by thousands of people, and I was walking through the crowd, and I still had my poopy suit on, and a lady with big breasts walked up to me and handed me a magic marker and said, ‘I want to know your name right here. I looked at her husband, and he said, ‘You’d better give her what she wants.’ So I wrote my name across her chest.”

The following day, they headed west toward Reno to reunite with their families. The crews became excited as they headed out over the Rockies because it was the first time they had seen snow in quite a while.

Touching down in Reno, the crews were welcomed as the heroes that they were. It was the last war for Gibbons and Fuller, and the last war for the RF-4C. Reno swapped out their RF-4Cs for C-130s in 1995, but not before putting on a dazzling, if not very ‘unconventional’ low-level display. (more on that in a later article)

Gibbons would continue in the Air National Guard for several years before he successfully ran for the House of Representatives, where he represented Nevada’s 2nd congressional district from 1997 to 2006. In 2006, he then ran for governor and won the election. He still lives in Nevada.

Fuller also stayed in the Air National Guard and returned to his full-time job as a firefighter. He also continues to live in Nevada.

Flying so many missions with Fuller, Gibbons stated, “It builds confidence. It builds confidence in your ability to recognize your teammates’ strengths and weaknesses. I was comfortable knowing he was the smartest backseater I ever met. He was not afraid to take on a risky mission. He became part of how I flew the airplane. I knew he would do things differently without telling him what to do. When you fly that long together, it builds your confidence, it builds your awareness, and it builds your success at the mission.”

Now living in the eastern mountains of Nevada, Gibbons ended our conversation by saying, “Nobody ever told me how hard it was to be a cowboy. It is a lot easier to be a pilot than a cowboy.”

Both Gibbons and Fuller talk regularly.

The 192nd retired their last four RF-4Cs on September 27, 1995, with the planes being flown to Davis-Monthan AFB in Arizona for storage. These aircraft were the last RF-4Cs in operational service for the United States. The High Rollers flew 350 combat and combat-support missions during Desert Storm with just six aircraft. Thirteen of the 23 aircrew would receive the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Contact the editor: Tyler@twz.com