A U.S. government report released earlier this month includes the best look to date at exactly how the U.S. Navy’s future Constellation-class frigates will differ from the Italian design from which they are derived. A core feature of this acquisition program, originally known as FFG(X), was the selection of a ship based on an existing, in-production warship in order to help keep costs and risks of delays low. It is now known that the Constellations will be longer and wider and displace hundreds of tons more than their “parent” design, among other changes in the hullform, superstructure, and internal configuration.

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) released the latest edition of its report on the Constellation class on Sept. 15, 2021. It included an infographic, seen below, which the Navy Office of Legislative Affairs had supplied to CRS and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). That graphic has significant details about the dimensions and other features of this frigate design in comparison to that of the Italian subvariant of the Fregata Europea Multi-Missione (FREMM), or European Multi-Mission Frigate. FREMM began as a Franco-Italian program that produced a different subvariant for each country. Additional examples are now in service with the Egyptian and Moroccan navies. The Navy selected the FREMM-derived design, which will be built by Wisconsin-based Marinette Marine, a wholly-owned Fincantieri subsidiary in the United States, as the winner of the FFG(X) competition last year.

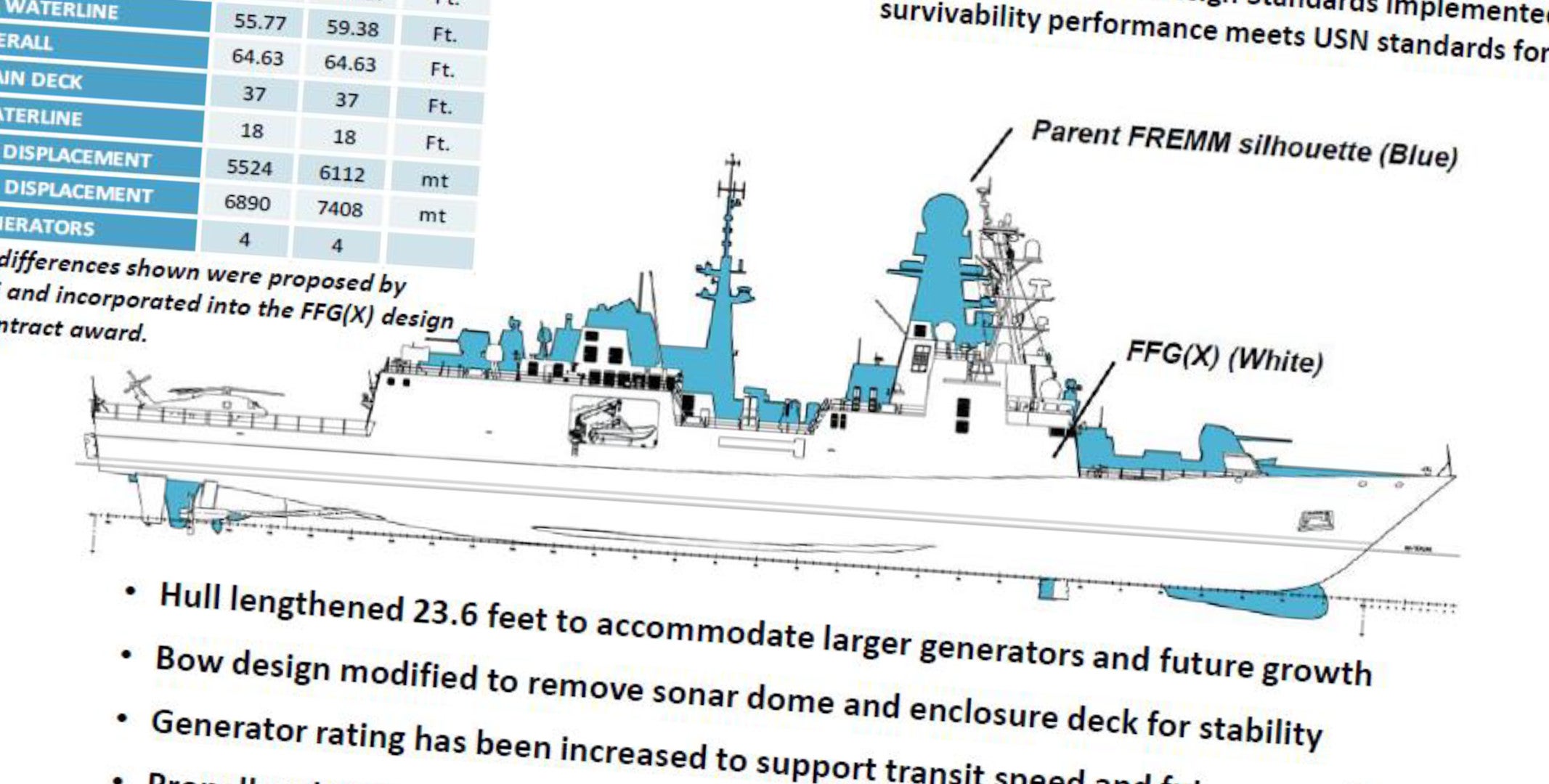

The infographic shows the “primary differences between the FFG 62 Class [design] and the FREMM Parent design,” the Navy said in an accompanying information paper, according to CRS. Compared to the Italian subvariant of the FREMM, the Constellation-class frigate is nearly 24 feet longer and just over three and a half feet wider along the waterline. The American warships are also expected to displace 518 metric tons more with a full load.

“Hull lengthened … to accommodate larger generators and future growth,” the Navy’s graphic says. “Generator rating has been increased to support transit speed and future growth.”

The greater displacement is linked to provisions made in the design from the very start to accommodate the integration of new and improved systems as time goes on, as well. It was already known that the Constellations would have a significantly different superstructure, with a much lower profile overall, based around the Navy’s requirements to integrate various U.S.-specific weapons and other systems, such as the AN/SPY-6(V)3 Enterprise Air Surveillance Radar (EASR) and a version of the Aegis combat system. You can read more about what the expected capabilities of these frigates will be, as well as what new features they might be already set to gain in the future, such as directed-energy weapons that would require additional power generation, here.

The Navy’s graphic also shows that the sonar dome found under the bow of the original FREMM design will not be found on the Constellations and that the propellers on the American warships will be “fixed pitch for improved acoustic performance.” The elimination of the sonar dome would indicate that the Navy has decided against a “low-band hull array,” which had been suggested as an option initially, in favor of the AN/SQS-62 variable-depth towed sonar array. The AN/SQS-62 is expected to be part of the still-in-development anti-submarine warfare (ASW) mission module for the Navy’s two subclasses of littoral combat ships (LCS), as well.

Perhaps most notably, the infographic says that “all differences shown were proposed by Fincantieri and incorporated into the [company’s] FFG(X) design prior to contract award.” This is significant given reports that emerged last month that indicated that the Navy had asked Fincantieri and Marinette Marine to enlarge the Constellation-class design after selecting it.

“The Italians did a very good job in the design of the internal spaces, and the flow of a lot of those spaces,” Navy Captain Kevin Smith, the Constellation-class program manager, had said during a talk at the Navy’s League’s Sea Air Space conference on Aug. 2. “You could say we bought a bigger house, [but] from a modeling and simulation perspective, it’s exactly the same.”

Those remarks had raised questions about the potential for cost growth or schedule delays due to significant changes in the ship’s design, despite the Navy’s touting the use of an existing, in-production design as a starting point. The information the Navy provided to CRS and CBO makes clear that this growth had occurred before the award of the initial FFG(X) contract. Whether the changes might still result in the ships being more expensive or more complicated to build remains to be seen, though the service has, so far, dismissed any such concerns.

It’s also worth noting that Navy “program officials stated they will complete the [Constellation class] critical design review and production readiness review in summer 2021 to support construction start in October 2021, 9 months sooner than previously estimated,” according to an annual report assessing progress on various major U.S. military programs that the Government Accountability Office (GAO) released in June. “The Navy said the updated schedule reflects the maturity of the ship design selected for the April 2020 award. Program officials noted they expect the Navy to review the basic and functional design for the ship’s 34 design zones prior to construction start, and for each major construction module, the shipbuilder plans to complete the detail design and construction drawings before starting the module’s construction.”

The Navy has reportedly been considering the possibility of hiring a second shipyard to produce a batch of these frigates in the future to help prevent delays in delivery or even accelerate production, as well as support America’s shipbuilding industry. Right now, the service wants the first of the frigates, the future USS Constellation, to be delivered by 2026. In May, the Navy exercised an option under its existing contract with Fincantieri Marinette Marine to buy the second ship in this class, expected to be named USS Congress, but no target delivery date for this frigate has been made public yet. GAO says the Navy’s current plan is to reach initial operational capability with the type in 2029.

The Navy’s contract with Fincantieri Marinette Marine also includes options for eight more ships. At present, the service’s goal is to buy at least 20, in total, in the coming years, but that number could easily grow. The Navy has made clear it is very interested in expanding and modernizing its fleets in recent years, driven in no small part by concerns about the continued growth of China’s naval capabilities. Congress looks set to add money to the Pentagon’s proposed defense budget for the 2022 Fiscal Year to buy more ships of various kinds, among other things.

Regardless of how the Constellation-class program progresses from here on out, we now have a much better understanding of exactly how these ships will differ from the original FREMM design.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com