The Bolt-M, a machine-learning infused strike drone that puts lethal precision firepower in the hands of individual soldiers, is a system that TWZ has followed closely since it was first revealed back in October 2024. Now, with the recent announcement of a $23.9-million contract to provide the U.S. Marine Corps with more than 600 Bolt-M systems for the next phase of its Organic Precision Fires-Light (OPF-L) program, starting next month, we sat down with its manufacturer, Anduril. Not only were we looking for an update on the program, we also wanted to get a much better understanding into the very high-profile firm’s thinking on one of the fastest moving facets of the defense sector today — short-range kamikaze drones. In order to do this justice, we went in-depth in a wide ranging discussion, from how Bolt-M is intended to be used, to the justification for its cost, to exactly how Anduril could scale production and how quickly they could do it.

The Marine Corps contract for the Bolt-M comes after 13 months of testing and will see the drones delivered to the service between February 2026 and April 2027. The OPF-L program is designed to provide dismounted Marine infantry rifle squads with a man-packable, easy-to-operate precision strike capability to engage adversaries beyond line of sight. Under this initiative, the Marine Corps should first get its hands on the Anduril drones sometime this summer.

Already during the testing phase, Anduril delivered an initial tranche of more than 250 Bolt-M systems to the Marine Corps as well as more than 300 to an undisclosed customer; this was achieved within five months of contract award. This has helped the company work toward its plan to scale production across all Bolt variants to a sustained rate of more than 175 systems per month.

TWZ Editor-in-Chief Tyler Rogoway talked with Dan Leighton, GM for Precision Engagement Systems at Anduril, starting with a look at the background of the Bolt-M.

Tyler Rogoway: Why did you create Bolt-M?

Dan Leighton: There are a lot of things in the field, and that kind of drove us to think about how we can differentiate ourselves there. As you know, modern conflicts have shown that lightweight man-portable munitions really are able to provide an asymmetric advantage to ground forces and mobilized forces. And in order to use that effectively, we need to have these in large numbers, with low cost. In our opinion, lightweight man- and vehicle-portable, reliable munitions that can deliver what we used to consider ‘outside’ performance; it’s like our old catch term, but we’ve really shown that this is ‘inside’ performance for our type of vehicle, and it is doable.

One of the theses that kind of drove the development of this vehicle was: how do we do this without having to have extremely talented, professional-racing-level FPV operators? In a discussion on exactly why that was needed, a small team of engineers in 2023 realized that we could probably do it and make a pretty capable item. And one thing I love about Anduril is that everyone got the opportunity to do that. That’s one thing that you’ll see me say over and over again: one of the things that keeps me really inspired and pushing Anduril is that we have an environment that constantly fosters the team to not only advance items but to center the advancements around: how do we go from a development item to something that we can bring to a production and fielding mindset?

Making things once is super easy, but making things that actually work in the field is extremely hard, and so it’s really what drove that team to see how we do that better based on the vehicles that we make, and the vehicles we’ve seen elsewhere. They showed a bench-top model to me and a few others, and it quickly became apparent that this could really be a differentiator for the warfighter and actually be a viable product and business model.

So we created Bolt, which was our loitering munition. We designed it from day one, as I mentioned, again, with users not only in the mindset of the engineers, but also next to them. We took feedback, requirements, and experience. We talked to the numerous veterans here in Anduril and made many of them fly the initial aircraft. We took soldiers, Marines, other users of modern conflicts, and then talked to a whole host of civilian FPV and drone operators in business as well, about what worked well, what could help them in their overall daily tasks.

It kind of became apparent that we had a few key tenets that we had to hit on. We had to hit on man-packable, had to be mobile, had to be highly effective. You can make a really good drone, but actually applying effects is something entirely different. Reliable, of course, but in a producible system with a low cognitive load. We kind of designed Bolt from day one around those tenets and kept coming back to that: how do we make sure we do that? Because that’s what we think are the key items to make this successful.

The warfighter is saturated with activities, and we wanted to be able to expand that lethality without having to sacrifice situational awareness or their mission. It doesn’t matter if you bring a better level of lethality to the Marine or soldier, if they have to choose their life or situational awareness to use it. So we used those feedbacks, those design tenets, and kind of created what we call Bolt as our base configuration.

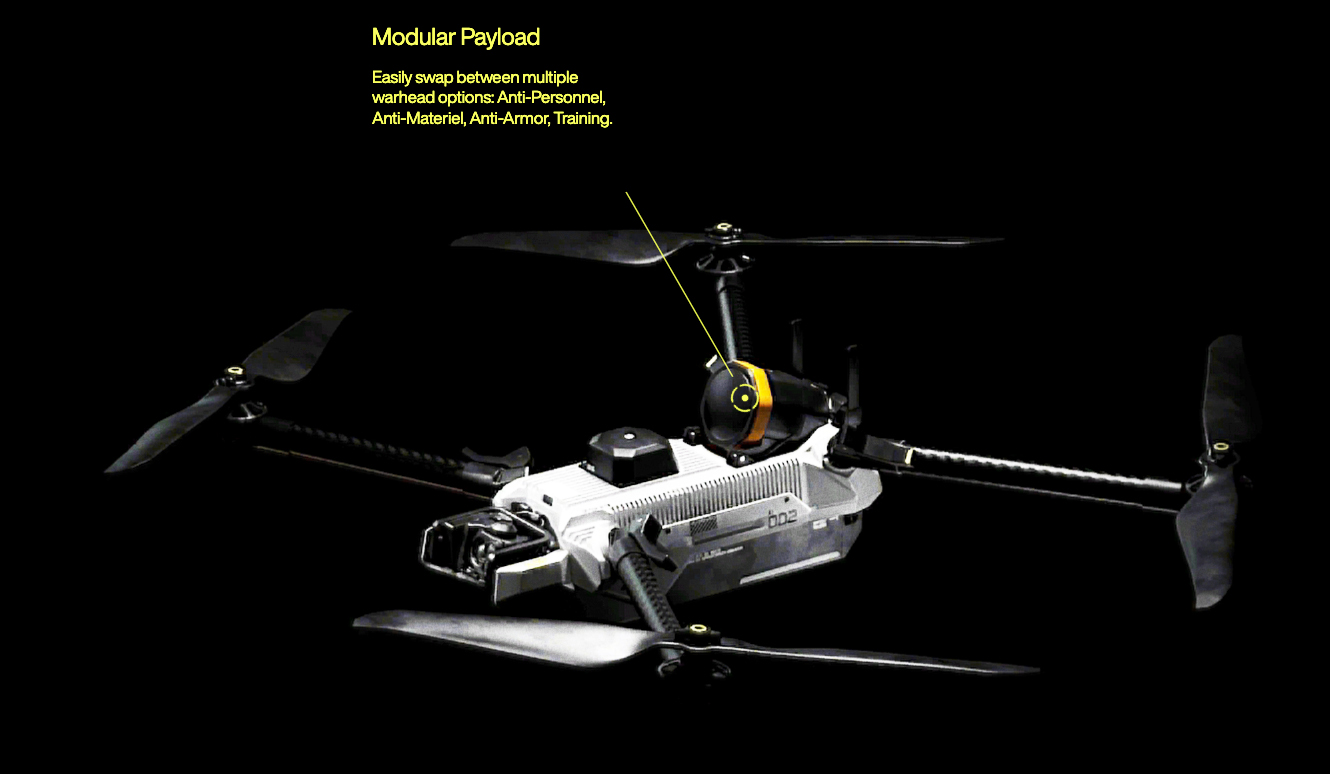

So the original one was autonomous, long duration, a man-packable system that really catered towards ISR missions, surveying. And so then we looked at: how can we do this for ground forces? So we took the vehicle, and then we had an armed variant, which is called Bolt-M, which has that lethal precision and configurable firepower, which is really one of the key things we also looked at as we went through the configuration.

No mission’s the same. You need to be able to adjust the vehicle to do what the missions need, not the other way around. We saw a lot of items that were like, what can we do with our vehicle, and how do we make our mission work with that? We want to change that core tenet and go to: how can our vehicle do what they want to do in their overall mission set? And so in order to help with that, we had a really good look at our onboard software UI [user interface].

So, as you’re aware from Anduril, we are very proud of our Lattice UI software, and we are able to utilize that to really automate our flight tracking requirements. The goal is to give the operator four simple decisions to make and be able to engage with just those. So where to look, what to follow, how to engage, and when to strike. All this results in something that someone can do with a heads-up display, can easily be taught, and we can do waypoint navigation, strike missions, or ISR missions.

We have about 40 minutes of endurance, a little over 20 kilometers in range, depending on the configuration. You can push to 30 and 40 if you have to. And it’s been a pretty effective system so far.

That kind of brings us to the U.S. Marine Corps. The Marine Corps in 2024 came to us and said, they heard about it, so we showed it to them. And we ended up going as an offering for OPFL, Organic Precision Fires-Light. And in 2024, they awarded us and two other companies as test beds for that system. We delivered the first ones in December 2024. So it was just over a year ago, and we were able to get 250 Bolts in our system. We continue doing R&D and parallel that on our own side, outside of the Marine Corps funding, and the last 13 months, the Marine Corps has really put us through the wringer. We’ve done user experimentation. We’ve done environmental validation. We’ve done flights in multiple conditions, we’ve done extensive training for high-end operators and low-end operators, and some people we pulled literally from the stock room to go try to fly the vehicle to see how hard it was. We used that all to kind of validate what we see now as Bolt’s baseline performance for the safety, environmental, and overall variance of mission sets. As a result of these tests and some others, the Marine Corps awarded us a contract this last month for $23.9 million to extend that OPFL system, putting over 600 Bolt-M systems [into production], which we’ll start working on here in February 2026.

The real thing that’s exciting about that, though, is that they’re taking these from like a training asset, and we’re actually going to be implementing with their tactical formations now. So we, along with some of the vendors, will now be in the hands of the actual users working through their mission sets, working part of their training. I’m really excited to get that feedback from them to see how we can best integrate them and what we can take from those lessons to help improve it. And then show how Bolt can really help them close that gap that we see there.

Really, the other big element of Bolt is the production factor. I’ve lived in the design-to-production world my whole life. And that transition is one of the hardest things, in my opinion, to do well. And so that was why one of our core tenets early on was: this thing needs to be producible at scale at a reasonable cost. In just over a year, we went from a handful of prototypes, we’d rolled out the initial five to the customer, to let them fly. And we’ve really created what we consider our modern and efficient production line that I’ll be using as a baseline for other vehicles.

So we revamped our design engineering, our supply chain quality manufacturing, and went from that prototype design line to a production line that can sustain 120 vehicles per month. We’ve shown surge capacity up to 240. And due to demand in 2026, we’ll be increasing our sustained rate up to about 175 units a month. I’m hoping to maintain a surge rate of over 200, up to even 300 if the need arises. We tend to stress test things very early, and so we had an opportunity come up, and we were able to push a big initial batch through that updated production line in Q4 of last year, after we had some late customer demand. The team looked at it and took the challenge, and we were able to produce over 300 Bolts five months after contract award, of which about 260 were produced in one month. So it was a clean effort and really showed the top end of our surge capacity, and we essentially did the first month of the new production line at full surge capacity.

A lot of lessons were learned from there.

We’re definitely taking note of those in the next year, but it really showcased what the team could do. We took what we wanted to do and ran it forward and really showed we could deliver these products at this level, at a reliable speed, and in scale that we need to really affect warfighters and DoW operations at large.

TR: Can you give us something like a scenario, maybe something you guys have already mapped out, for an ideal-use case for Bolt-M, in regards to the Marine Corps?

DL: We’ve had a lot of conversations with the Marine Corps, and there’s a myriad of uses.

So you do a mortar team, or are going into a localized marine assault, right? They’re either taking the beach or have the beachhead and are looking out for initial insertion to a country or a localization. And you have the choice of either going in at a squad-level blind or getting an ISR asset in the air, if you have one on site, that’s quiet enough, or using a mortar team for back-end fire or calling artillery fires required, right? Your mission set of what you can do, based on what your rules of engagement are, and what the target’s doing.

So we’ll do this in the case where we don’t have background artillery, just for simplicity, and you are going into an area where you don’t have any ground forces directly assaulting you or helping you, you have no active air engagements at this time, even though it’s typically kind of unrealistic. We ran this drill with the Marine Corps a couple of weeks ago. And so we pointed out that we probably wouldn’t ever enter with that type of scenario, but assuming you did, at this point, you’re by yourself, you’re alone. You may have a mortar team with or without you.

And the idea is, you’re in ruggedized terrain, and you know you have a target set coming towards you that you’re either trying to avoid or trying to engage. At that point, you don’t want to wait until you’re in visual range, whether it’s an anti-armor for a Javelin-type interaction, more of an Army co-op, but same idea for anti-armor, or if it’s personnel or a vehicle coming to assault the area for, say, a rescue mission, you want to verify that the assault crafts don’t make it to within firing range. So getting comms and heads-up that things are coming towards you, there’s either threats, again, for rescue missions, or a threat you’re trying to actually engage.

We do a pretty good, usually, overhead visibility with ISR assets, Predators, and other things to let you know in the general region that there’s movement. But beyond that, getting an actual tactical solution that you can engage with is a challenge. And so that’s really, to me, what these OPFL systems bring to you, is that if someone hears that there’s a vehicle coming towards you, and this is a scenario that one of the Marines walked us through in real life. They saw it turn off a road into the covered region… And they were like, okay, it is five clicks away. We know it’s coming towards us. We know the general direction, but we don’t know it’s undercover now, and we can’t tell where it’s coming from. At that point, they could pull a Bolt out of their backpack, launch it, and have almost an hour of flight time with the ability to do thermal recognition of the vehicle. We did this test in a forest region where we had to locate a vehicle driving through the forest. It was pretty short range, only like five kilometers… We detect the vehicle and track it the entire way.

And what differentiates it is that we’ve had a lot of drones that aren’t armed. You can see the target all day long, but they’re still coming towards you. And if you see them splinter off, say it’s a caravan of two vehicles, they break away, you may only have one vehicle to pursue. There are also people who can drop forces off who can spread out from that point. And so, not having the ability to actually engage and do something about that target really is a challenge. Knowing is one thing, but being able to operate it and engage is another. So being able to take that Bolt, use it as an ISR asset, if that’s what’s needed, and that’s the CONOPS [concept of operations] rules of engagement require, but have the ability to strike the vehicle if it turns out that the threat is coming towards you, and then you need to eliminate in order to complete your rescue mission.

You could do high-fidelity video and identify even personnel at a decent range. I can recognize my coworkers’ faces as they’re flying around in the near area. So you’re going to do that with a high-fidelity solution so you know it is a threat that you need to eliminate. And you’ll do that at a safe standoff distance to ensure the success of your mission. It really differentiates from the mortar fires, artillery, or having to send units to separate to hold a perimeter while you go back.

TR: So would it be safe to say Bolt-M provides, at the lower end of the spectrum, an individualized end-to-end kill chain solution in one vehicle, more or less?

DL: Yeah. The other thing is, because we are returnable and we’re pretty high density in terms of carrying, you can launch multiples, coordinate maneuvers to have spread out along the perimeter. You could do ISR-only missions because you’re returnable. You can fly out if you deem it a civilian or if you deem that it’s not high enough of a threat, or if it veers off to a different direction away from you. Instead of giving away your position, you can return the vehicle back to you, disarm it, and put it back in your backpack. We’re not a one-way vehicle that has to crash land somewhere. You could really leave without having given away where you were at, where you landed, and where you took off from.

TR: Is it kind of an unlimited-use vehicle if you just use it for ISR? Kind of like a normal drone that somebody would buy?

DL: Yeah, exactly. And most people will break it before they run out of the use cases.

TR: Okay, the Marines are ordering 600 now. Now, this is a tiny number, let’s be honest, in the scope of what we see with warfighting today, especially with Ukraine, which is burning through potentially millions of drones of all types. You said that you could scale up quite a lot to hundreds a month. Do you have a larger plan if the demand signal came to get into the thousands?

DL: Currently, we have a production line scaled to meet our production needs and demand signals today, plus some edge cases… But we are very confident in our ability to scale beyond that. I have multiple plans to build thousands to tens of thousands a year if required. Obviously, that will not happen overnight. I started my life in manufacturing production. I will never say that’s an easy transition to happen, but it’s something that we’re pretty confident we can do.

We actually had a good stress test of this on Bolt. We ran an original block variant — that was what we supplied to the Marine Corps. A lot of those lessons that I mentioned from the users also came from our production. There are also a lot of lessons for the production line. We built the first Bolt to be manufacturer-producible. That was, like I mentioned, one of our core tenets. When you start building it, you always learn things. There’s always a gasket that was a problem, or a close relief, or an area where cables got pitched. As trivial as that is, it actually was one of our bigger challenges earlier on with some of the original routing.

And so we really took that and took it to a block two revision to say, okay, how can we make this in the scales of thousands that I agree that a real conflict and a real differential would need? And so we actually did a block two driver, almost purely for manufacturing. There’s a performance improvement we coupled with it, but the main driver was to get to what we consider sustainable design well before we had to hit that sustainable rate. And so, as I stressed, we had our original production line, and we actually stood up a second production line for that big push I mentioned in Q4 and ran them in parallel, duplicating them to showcase that we could scale this essentially as required, with additional cells to meet demand. Given the production we have now, we’re going to put a third cell up shortly to have that additional sustained-rate demand that we talked about. Our intention would be to start merging those, and those would bring us into the high hundreds a month, easy.

I don’t think with a breaking down cell, I’d maintain individual cells at up to 1,000 a month. But at that point, we would condense them into subassembly regions and go from there. So we’ve thought through that evolution plan and how to go from what are discrete parallel lines, to get us into 150 per line and scale that. I think I have room for nine separate ones today. And before I probably do nine, at the five to seven mark, I break it into how do I go to another industrialization effect and break into the lower, bigger sub-assemblies, and then start building those in sub-assembly batches that I could get to the thousands a month if I needed to. That wouldn’t happen overnight, but it’s something we put a lot of thought into. And I think that for this to be effective, you really have to have thousands, tens of thousands of these in the field and go for it.

TR: As for the cost, let’s assume that it’s not hundreds or low thousands of dollars. Let’s just say it’s higher, which I’d imagine is the case. What capability would something like this give the troops in the field compared to an FPV drone that Ukraine is building at, let’s say, $1,200, or $1,500? What are you offering that it doesn’t have? And what is your business case in comparison to something like that?

Author’s note: Following the interview, the company declined to give us a specific price estimate for the drone but did offer some important color, stating they cost in the “tens of thousands of dollars” each, adding:

“Bolt and Bolt-M are designed to fill the gap between improvised/hobby-shop solutions and expensive, exquisite solutions. Specific costs for Bolt and Bolt-M depend on configuration and payload, as well as order volume.“

DL: My favorite question. That’s actually what I pushed the team on when they first pitched this to me! I’m like, why wouldn’t I just buy an FPV? And they definitely convinced me of it. I’m fully drinking the Kool-Aid on it now.

So a lot of things… First one is, you know, we’ll do a $1,500 popsicle stick, I’ll call it, you know, an FPV that is effective, carries a munition, and can fly. Usually, they’re analog, which definitely has its advantages, but it’s pretty easy to jam. It’s not resilient comms. Usually, you don’t have bespoke guidance at that low cost, some of the $5,000 range drones do; you have some better guidance. This still requires a pretty talented FPV pilot to be on the sticks the whole time flying, moving forward with it. And that is not only an operational challenge, but it’s a training one. I have several FPVs, I have several drones. I’ve tried to train many people on them. Yeah, flying a DJI Mavic the first time to do a simple go-forward-and-back is an easy mission. In a real-world scenario, you need someone who has extensive training… I prefer not to create an entirely new operating condition and have it added to their [a service person’s] effectiveness and their role. And so the training cost, overall resilience.

There’s also resilience for environmental. So Bolt is fully environmentally sealed for full cold weather conditions, full warm weather conditions. In the extreme cold and extreme temperatures, especially full sun and desert environments, or in Eastern Europe, extremely cold environments, FPV drones are definitely challenged with snow, ice, accumulation on lenses, battery performance, all those degrade, and it is a challenge.

So you have training, you have overall ease of use, and then reliability.

And the last one is effectiveness and not reliability from a performance set; it’s reliability from a mission set. We carry a — we used to use the word outsize, in my opinion, it should be normal size for this — warhead. I want to set the bar for that energetic capability on the Bolt-M variant. We’re able to put a shocking amount of firepower on this small drone, which I think really is the bottom end of the effectiveness.

We did a series of tests and asked: what is actually worth bringing out the vehicle to do a strike mission, and what payload do we need to do that effectively? I’ve talked to some users, and it’s really normal to launch five, 10 FPVs, go ahead and strike with them, and hit them [a target] over and over again. And we talked about attrition rates. I talked to one user. He said that the attrition rates on a strike mission were sometimes up to 80%. And so they’d be like, hey, is two enough? So, yeah, two wasn’t quite enough to fully engage the target. They partially disabled it, didn’t permanently damage it. So our goal was: we shouldn’t have to send 10… We shouldn’t be sending 10 things to have two of them get there and have that not fully, permanently disable the target. And so Bolt does bring that level of firepower, that resilience, that reliability.

There is a trade-off. It’s not going to be fully survivable for a half a million dollar strike mission, but there is, I think, a use case for lower cost more attritable assets, but it still in my opinion, needs to be able to do that mission without having that type of failure rate and is still going to be effective once it actually gets there. And so we start kind of putting all those together. That all looks really good on paper, in my opinion, but I’ve done a flight mission with a Bolt, and I’ve done multiple simulated flight missions with FPVs. And there’s definitely a differentiator on how effective we can be as a system, and how we can actually be really used in a mission set downrange.

TR: I’d imagine that would also port over to time-sensitive targets where you have a much higher probability of kill than with a low-end FPV drone, which could mean saving the lives of friendly troops, too? This is something we’ve seen; we’ve talked to people in Ukraine, and the effective rate is very low.

DL: In a full trench-warfare scenario like in Ukraine, where they are hurling hardware across the FLOT [forward line of own troops] and hitting targets of opportunity, lower-cost FPVs might make sense. But that’s not really how our DoW intends to fight modern conflicts, and even for the Ukrainians, they’ve asked, when I talked to them, about having something for time-sensitive, mission-critical targets, where they can have a higher success rate and a drone that’s more reliable and more resilient. Because even for them, they have those scenarios. It’s not always just opportunities. There are mission sets that they have to perform, and just a 20% success rate sometimes is not enough, and that’s by no means all of them — there are other ones that are better — but it’s definitely one of the key items I think we need to supply the warfighter with.

TR: What types of targets can it kill?

DL: I definitely can’t go into specifics on that one; we do have a multitude of payload options. So we have flexibility, from smaller targets, which give you a higher range and obviously lower penetrative effects, and have a wider area of effect. And we have more targeted ranges for heavier targets that can do a more precise engagement with some implications for performance.

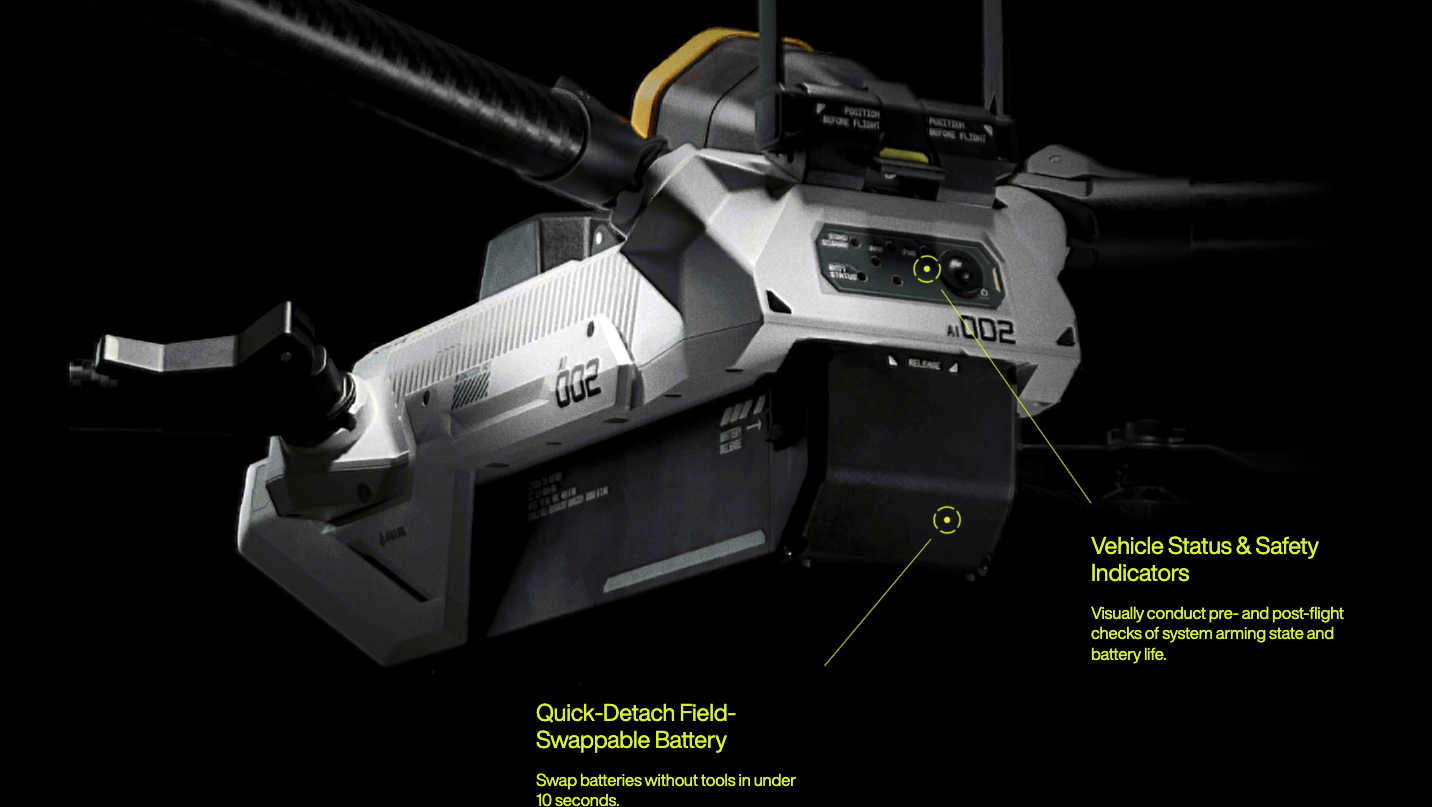

The warhead is removable, and so you’re able to change the mission set on the Bolt with just a handful of options. Snap it in. The Bolt auto-recognizes it, changes the performance characteristics to match, and loads the mission set for you based on the payload you loaded to go do it.

So we really bring that flexibility to the user, so they can determine the key target, load the right mission set, and get going, and know that you can always swap the actual munition and it goes forward. So we’re constantly developing new payloads for it to increase that use case.

TR: Has this been used in combat anywhere? Have you guys taken it to Ukraine at all?

DL: I can’t go into specifics of where it’s been utilized.

TR: Will Bolt have cooperative capabilities for swarming?

DL: It already has what we call multi-asset maneuvers, and we are looking at how to further utilize those based on the feedback from customers.

TR: Can you kind of just give us a comparison to say, a Switchblade or something else that’s out there? What are the differentiators between you and, let’s just say, a Switchblade 300 or 600?

DL: Again, I think the tenets we discussed earlier really are our differentiation. We took what we thought was the lower cost, more attritable, more flexible, squad-level mission use case of those FPVs, and decided, how can we do those types of mission sets with the energetics, the firepower, and the reliability and ease of use of these larger systems? But we also wanted that reliability. We also wanted the larger firepower of those bigger vehicles. And really, that’s what became Bolt. It’s a hybrid of those two categories, and there’s not a lot that goes between them.

So we took those two pieces, those two pillars that we currently have in our forces, and we needed to create a system that kind of works the best of both of those worlds with far fewer trade-offs than even I anticipated originally. We surpassed several performance milestones that we were targeting as we thought a hybrid approach would be a compromise of those, where we can hit some of the ranges and payload requirements of those larger vehicles, but still have that return to base, still have that flexibility by not taking the negatives of the very expensive system and highly trained operators and highly complex systems of the FPVs… So then we kind of create a system that bridges that gap. And this is why we think it’s kind of a differentiator in there.

TR: In Ukraine, the biggest problem that we’ve heard is the speed of adaptation to all types of battlefield conditions. So it’s not just one thing or another, but with the lower-end drones, it’s definitely the electronic warfare environment. Instead of months and even weeks, it’s days or even hours until updates are needed, software, of course, but sometimes hardware as well, to get them where they’re effective at all. How does Anduril plan to address that very challenging sort of high-speed battlefield adaptation model with Bolt?

DL: Yeah, so that is something that I continually think about, and the team here is currently focused on. It is not a static environment. There is no one answer. And one of the key things with Anduril is, and why we built the Lattice backbone into it, was to address that.

If we can think of it, then our adversaries will think of a way to stop it, and continue the back and forth that will always happen. So you have to think about that from, ideally, day one. And if you don’t, you should start thinking about it on day 50, or wherever you’re at. For Bolt, we really looked at that from the Lattice backbone, being able to roll software updates and do key countermeasures as required with that software ability, whether that’s on the controller level, whether it’s on the vehicle level, to be able to quickly and effectively address these concerns requires a handful of things.

First is knowing that they happen. So it’s having the infrastructure, the fleet management, and the team ready to support those products, which we are 100% dedicated to, to know that and to get that feedback right away, not just sit on corrective actions that have been there for years, address them, immediately go in to see how we fix it, and then immediately bring those solutions to our customer sets. That’s one of the key items that we bring to it.

The most common problems I have, is actually getting adopted by the customers at the speed we developed the fix at. I have an entire team who’s looking at our fleet, determining what is happening: are we still being as effective as we used to be? Or if we are not, how can we change that? The majority of times it’s the software, but there are resilience issues from a RF environment, GPS-denied areas, even defensive measures. And so there are some hardware elements. Ideally, in a production line, you want to maintain the same products forever and never change it. But that’s not realistic with current supply chains and current conflicts. So the goal is to know: when does it make sense to change the hardware?

TR: And do you see your company’s work in the counter-UAS space as a kind of a cross-pollinator of getting ahead of potential issues that you might see in an EW environment?

DL: Always. I would say the same answer for all of our flight systems. I encourage the team to really reach out to all our partners, both in Anduril and in the DoW, and in other industries. I think not using the resource at hand is always a fallacy, and then we should utilize our own EW experts internally. There’s some DoW, there are seminars, there are pushes. There’s a lot of information you can gather, and to be utilized. You just need to make sure that you’re being realistic with your expectations, being communicative with the customer, and then constantly trying to see how you can improve it.

TR: Is there a fiber-optic wired potential add-on to Bolt, and what about potential communications relays for extending the line of sight?

DL: So, robust comms. It doesn’t matter what vehicle you’re flying; you need to have robust comms. As I mentioned earlier, it’s a dynamic environment. There are some core tenets. You need to talk to it. You need to be able to talk to it over varied terrain. You need to be able to do your mission operation in varied terrain and in denied and non-denied environments, whether that’s fiber optics, whether it’s radio relays, and then autonomy, where it makes sense, all of those can allow the vehicle to do its mission set in a realistic scenario.

I can contrive 1,000 scenarios where a DJI Mavic [consumer drone] would be the most effective strike vehicle in the history of the world. But in real life, there are a lot of challenges where vehicles would fail in an actual scenario. So it’s taking those CONOPS, those design mission sets, and finding how the vehicle can be most successful in those, whether that’s fiber optics or that’s relays. I will say, we were looking at all options, and we have a pretty good solution set to make the vehicle effective in those environments.

And one of the key options is autonomy. The first thing I always say, there are key decisions the human needs to make, and so what we do is we use our Lattice backbone to drive the autonomy so that we make it as easy as possible to make those answers with as much time and fidelity as possible. If you’re flying, you’re doing this, and you’re interacting and trying to fight columns and trying to do the tether for fiber, all of those are taking that cognitive load. We prefer to solve that solution for the user and have them just spend the time interrogating the target and determining what they want to do properly. It makes them more effective and that makes them a safer item with less collateral. And so using that autonomy to help bridge comms gaps, to help do anything like that, but always still leaving that human in the loop for the key critical choices that we want them to make.

It is one of the items that I think Bolt has done very, very well.

TR: Okay, final question, the Lattice software, there were reports that there were some cybersecurity issues with it. Obviously, the fear is these drones can be defeated before they lift off, via cyber attacks, cyber intrusion, whatever. What are you doing to harden Bolt against the cyber threat side of things?

DL: A lot. It is something we really take very seriously and look at what can be done. We stress test the vehicles a lot. As I said, things change: software changes, intrusion options change, even servers change. All of those are vulnerabilities, and you really need to look at the full end-to-end stack. We work very closely with our DoW partners and work with their cybersecurity teams to make sure that we’re hardening as well. We also have a very good, very strong internal approach to it. I’m proud to say, for the most part, I don’t think I’ve had the DoW yet find a hole or challenge that our cyber team hadn’t found first. We submitted some reports, and I think we had four times the findings on the internal side as we did with a third party we hired to go look at it. So it’s something we are constantly looking at.

We know that it won’t matter if you have an effective system if you can’t, again, operate in the environment, and cybersecurity, whether people admit it or not, is part of our operating environment. You have to have that as one of the key requirements to have a secure, reliable system. If someone can stop it through a hack or other venues, it doesn’t really matter how good the system is. And so it’s like looking at that as a whole picture.

For earlier drones, they didn’t see that as a key requirement. You had to do it, but it wasn’t really part of their mission sets. And I think in modern warfare, that’s just a fallacy. You need to have that continually running, continue to check, and continue improving. That back-end team I mentioned that is entirely dedicated to looking at how we can harden the vehicle and trying to get ahead of any threats and things that could come our way.

A huge thanks to Dan Leighton for taking the time to talk about Bolt in such detail with us and to the Anduril communications team for facilitating the interview.

Contact the editor: Tyler@twz.com