Seventy years since its first flight, the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress remains, remarkably, very much at the top of its game, as one of the U.S. Air Force’s three strategic bombers, and is still making high-profile deployments around the globe. Not only does it continue to add new weapons and capabilities to ensure its improbable service record, but its future is secure, and it will outlive the B-1B Lancer and the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber that were both previously expected to supersede it. With new engines, as well as a host of other upgrades already installed or in the pipeline, the mighty ‘BUFF’ will continue to fly with the Air Force alongside the all-new B-21 Raider, another stealth bomber. But with this week’s 70th anniversary of the maiden flight of the prototype YB-52, in the hands of Boeing test pilot A. M. “Tex” Johnston, it’s worth looking back at how the iconic bomber stood the test of time through progressively improved variants that responded to the operational demands of the changing security landscape.

Paper Projects

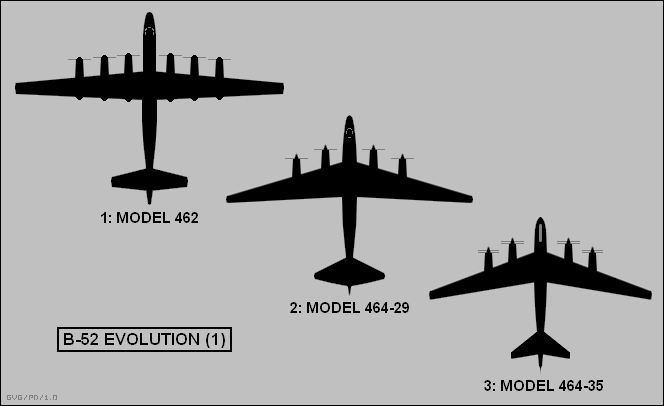

What became the B-52 began life with a Boeing response to a November 1945 strategic bomber requirement, although there would be considerable changes to the plans before the ‘BUFF’ finally took its familiar form. The original Model 462 design, for example, had a straight wing and would have been powered by six Wright XT35 turboprops. In many ways, it reflected the design philosophy of the company’s B-17 and B-29. In June 1946, Boeing won a development contract on the back of the Model 462, calling for a full-scale mock-up of what would now be designated the XB-52.

The Model 462 proved short-lived, the-then Army Air Force deciding it offered little advantage over the B-36 Peacemaker. Boeing quickly drafted the slightly smaller Model 464 instead, now with four Wright XT35s but with the same overall configuration as the Model 462. The Model 464 also won official support but Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, then the Deputy Chief of Air Staff for Research and Development wanted it bigger and heavier, and it was scaled up again, almost to Model 462 proportions. Predictably, perhaps, the new design was again rejected, amid concerns over costs and performance shortfalls.

Boeing persevered with the Model 464, however, refining it by mid-1947 as the Model 464-29, with a new wing of increased area and with 20 degrees of sweep on the leading edge and un-swept trailing edges. One element that characterizes the B-52 to this day was added in this iteration: the tandem undercarriage on the fuselage centerline, with outrigger gear under the wings. Still, the Model 464-29 didn’t meet Air Force requirements and it was almost canceled altogether, before LeMay stepped in to give Boeing more time to rework it again.

The Model 464-35 that came next benefited from the advances in aerial refueling, which now ensured it would meet Air Force range requirements while allowing the aircraft to be smaller and lighter. The Model 464-35 retained four XT35s, but these now featured contrarotating propellers, much like the rival Soviet Tu-95. The wing was also more sharply swept, with a sweep on the trailing edges. The tailfin, too, was swept back. Finally, with a promised range of over 11,000 miles and a maximum speed of 500 mph, the Boeing design could rival the B-36.

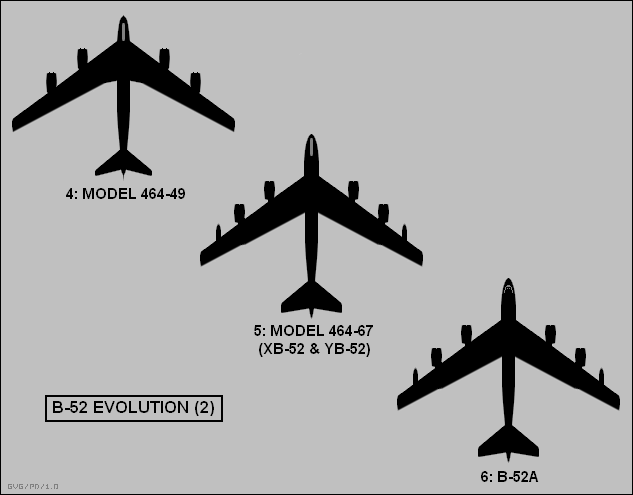

The next big step in the evolution of the B-52 was the Air Force’s decision in May 1948 to pursue a turbojet-powered version of the Model 464, which emerged as the Model 464-40, with eight Westinghouse XJ40 engines in four podded pairs slung below the wings. With this, another BUFF trademark was established. The limited reliability of early jets is reflected in the fact that the Air Force requested a mock-up and two flying prototypes of the turboprop Model 464-35, instead.

In October 1948 the Boeing XB-52 design team met with the Air Force to discuss progress on the Model 464-35 when service officials told them that they had changed their minds — turboprops were now out of the picture, due to problems with these powerplants combined with the promise shown by the jet-powered B-47. The day after the October meeting, so it goes, was a Friday. A member of the Boeing team called the Air Force and told them they’d have a jet-powered version of the Model 464-35 ready by Monday.

The Model 464-49, apparently drafted over a weekend in a Dayton hotel room, is what would become the XB-52 prototype. The design included eight of the then-new and highly promising Pratt & Whitney J57 turbojets in podded pairs, a stretched fuselage that compared with the Model 464-35, while the wing had more sweep (35 degrees) and was mounted further forward. The long, fighter-style cockpit canopy would later be dropped but it did appear on the XB-52.

With the Model 464-49, the Boeing team had finally won the Air Force over and it was a decision that the service wouldn’t regret.

XB-52: A Delayed Start

The XB-52, as the first flying prototype, followed the general configuration of the Model 464-49 design, but was still not a certainty for quantity production, with various rivals lining up, including the Convair YB-60, a jet-powered version of the B-36. With LeMay’s backing, Boeing had further tweaked the Model 464-49 to produce the Model 464-67, on which the XB-52 was actually based. Above all, efforts were made to increase the aircraft’s range to meet SAC requirements. The fuselage was stretched again, to boost the fuel load, for a combat radius of 3,070 nautical miles unrefueled, while the overall weight rose to 390,000 pounds. Another new feature that would be found on early-model BUFFs was the tall, narrow-chord swept fin.

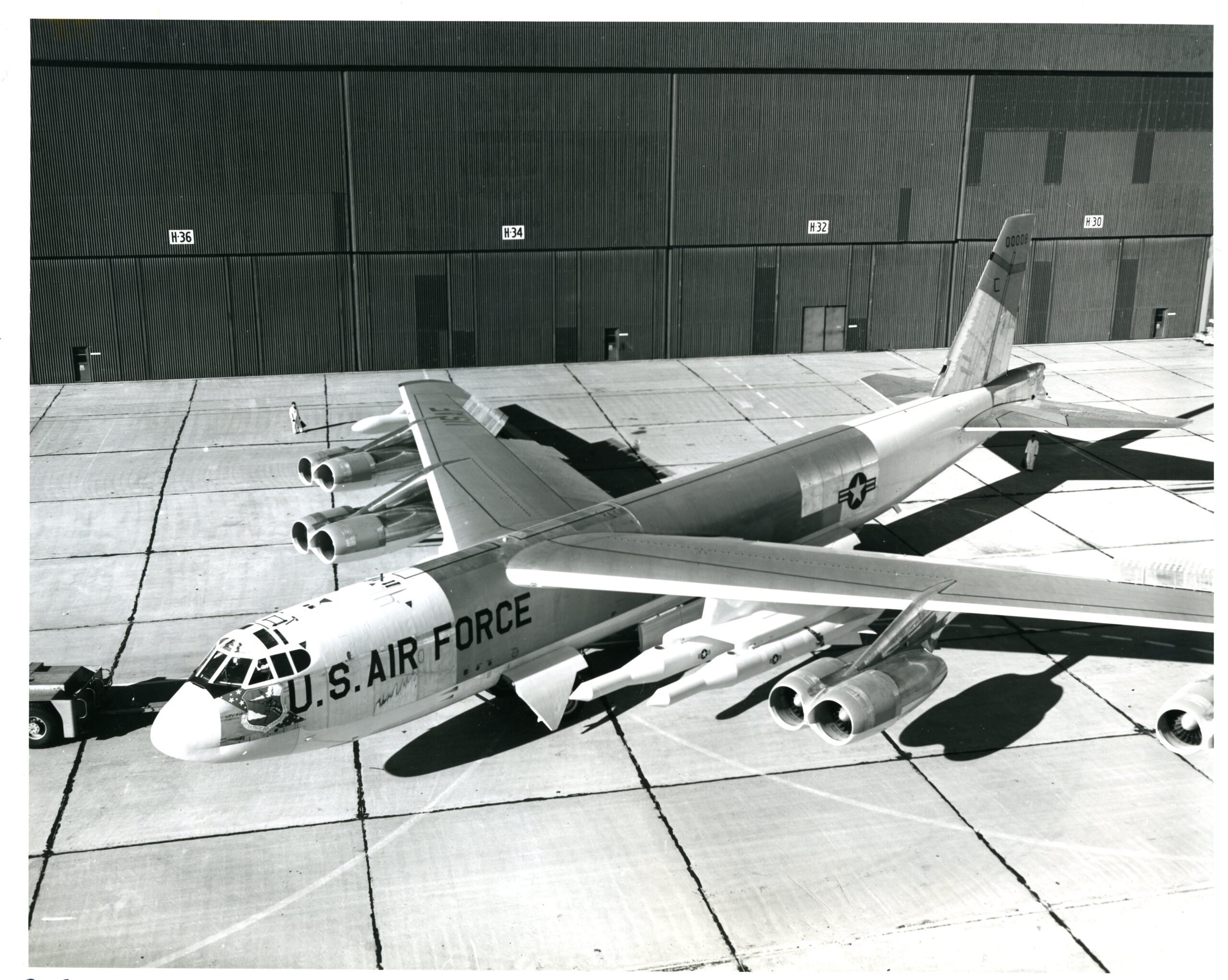

Only one XB-52 was completed, to Model 464-67 specifications, but it was the second of the type to fly, in October 1952, preceded by the YB-52. The six-month delay was the result of repairs after a failure of the pneumatic system during ground tests. In March 1953, the Air Force accepted the XB-52 but, like the YB-52, this historic airframe was later scrapped.

YB-52: First In The Air

Originally, the Air Force contracted for two flying prototype XB-52s and the reason for one of these being completed as a YB-52 — indicating a pre-production test aircraft — is not entirely clear. It may well have been a budgetary move, and the differences between the two prototypes were minor.

The YB-52 was the first BUFF to fly, from Boeing’s Seattle plant, on April 15, 1952, landing at Larson Air Force Base, Washington, after a flight of 2 hours 15 minutes.

“I am convinced that this is not only a good airplane, it is a hell of a good airplane,” test pilot “Tex” Johnston told reporters after the flight.

B-52A: Three For Luck

Buoyed by the promise of the XB-52 and YB-52, and with war raging in Korea, the Air Force in early 1951 issued a first production contract for the BUFF, to replace the B-36. This covered a batch of 13 B-52As, which would differ from the prototypes in their revised cockpit sections. With another LeMay intervention, the fighter-style cockpit canopy was removed, the pilot and co-pilot now sitting side by side. The electronic warfare officer was behind them, facing aft, with the navigator and bombardier below them on a lower deck.

Other changes included yet another fuselage stretch, uprated J57-P-9W engines, and rear-fuselage water tanks for water injection, boosting power on takeoff. The pace of the program was such that, although the B-52A was perfectly sound, the contract was swiftly modified to just three aircraft, while the others would be completed as RB-52Bs. The first B-52A flew in August 1954 and all three were used exclusively for tests, including the four-gun tail turret, first fitted on this variant. The most famous of the test BUFFs was also a former B-52A, the NB-52A being permanently converted as a mothership for the X-15 high-speed research aircraft program. It continued in this unique role until 1969.

RB-52B: Recce Intermission

The first of the operational variants was the RB-52B, the designation and dual role reflecting the fact that the Air Force Headquarters, initially at least, wanted the new aircraft to concentrate on reconnaissance missions. This ran counter to SAC ideas, which proposed pod-mounted cameras to be fitted only as required.

In October 1951, however, the Air Staff declared that all B-52s would, for the time being, be completed as reconnaissance aircraft that could be adapted for bombing.

Ultimately, however, only the first 27 aircraft were completed to the convertible reconnaissance/bomber standard, before further production of ‘straight’ bombers, known to the Air Force as B-52Bs.

For the reconnaissance role, the RB-52 was fitted with an equipment capsule that contained two dedicated crewmen (provided with downward-firing ejection seats) plus various mission packages, including optical cameras, electronic intelligence (ELINT) sensors, or different surveillance radars.

The actual missions flown by the RB-52s remain mysterious and the Air Force fairly quickly did away with the RB-52 designation altogether.

After a first flight in January 1955, the first RB-52 was delivered to the 93rd Bombardment Wing at Castle Air Force Base, California, in 1955.

While the first RB-52s retained the four-gun tail turret of the B-52A, with 50-cal machine guns, the remainder introduced the new turret with a pair of 20-mm cannons.

B-52B: The First True Bomber BUFF

After 27 RB-52Bs, the remaining 23 B-models were pure bombers, with no provision for the reconnaissance capsules. First flown in July 1955, the B-52B initially used the twin 20-mm cannon tail turret, although the last seven aircraft reverted to the four 50-cal machine guns.

Like the RB-52Bs, the B-52Bs were mainly used for crew training, a role in which they served until the mid-1960s. Another former B-model was converted as the NB-52B, to support the NASA NB-52A on the X-15 program. This aircraft, known as Balls 8, also served as a mothership to other air-launched vehicles, including the NASA Lighting Body series, the X-43 hypersonic test vehicle, and others, until finally retired in 2004.

B-52C: A Raft Of Improvements

Although only 35 examples of the B-52C were built, this variant proved that the basic aircraft had significant potential for further development, a fact that has kept the BUFF on the front line ever since.

These aircraft were heavier than their predecessors, powered by up-rated J57-P-19W or J57-P-29WA engines and had the same four-gun tail turret as the last B-52Bs. By the time production ended, the C-model was also fitted with a much-improved MD-9 fire-control system. While underwing fuel tanks were found on the B-52A and B, the B-52C was able to carry much larger auxiliary tanks, each of 3,000 gallons rather than 1,000 gallons. Other new equipment included the AN/ASB-15 navigation/bombing system. The option to fit the reconnaissance capsule of the RB-52 was retained.

The first B-52Cs began to be issued to the 42nd and 99th Bomb Wings beginning in December 1956. Latterly, the type served as trainers.

B-52D: BUFFs In Big Numbers

The first variant to be built in large numbers — 170 in all — was the B-52D and the production effort required two factories: the main plant in Seattle, plus Wichita in Kansas.

First flown in May 1956, the B-52D was very similar to the B-52C, with the same J57-P-19W or J57-P-29WA engines and MD-9 fire-control system for the tail turret. The major difference was the removal of the option to fit the reconnaissance capsule.

Later on, changes were made to optimize the B-52D for the low-level role, with tail clearance radar, Doppler, and low-altitude radar altimeters. At the same time, structural modifications ensured the aircraft was able to operate ‘down in the weeds.’

With the war in Vietnam, the B-52D was further modified, receiving the ‘Big Belly’ upgrade that increased its capacity to carry conventional ordnance through the introduction of high-density clips of bombs. While unmodified B-52Ds could carry 27 500-pound or 750-pound bombs, the Big Belly variant could carry 84 500-pound or 42 750-pound bombs.

Ultimately, the B-52D proved very useful, not only in Southeast Asia, and the Air Force ended up prolonging its service life, through the Pacer Plank upgrade, with the final operational examples being retired only in October 1983.

B-52E: BUFF On A Budget

Superficially similar to the B-52D, the E-model was similarly built in Seattle and Wichita, to the tune of 100 examples. A key advantage of the B-52E was its reduced price tag, a pre-inflation amortized unit cost of $1.4 million.

For that, the customer got all the features of the B-52D but also several new additions, including a low-altitude capability built-in from the start, the ability to use the GAM-77 (later AGM-28) Hound Dog nuclear-tipped standoff missile, and the GAM-72 (later ADM-20) Quail decoy.

With a strategic-only tasking, the B-52E was never used in Vietnam, the last of these versions being retired from service by 1970.

B-52F: The Hot Rod

The last of the ‘tall-tail’ BUFFs, the B-52F was also the last model built in Seattle and Wichita. These 89 aircraft differed primarily from their predecessors in having a new powerplant, with different sub-variants of the J57-P-43 offering increased power for a useful performance boost.

First flown in May 1958, the B-52F began to be delivered to the Air Force in early 1959. Once in service, it received a conventional munitions boost, under Project South Bay, which added an additional 24 750-pound bombs on underwing pylons, in addition to the 27 that could be carried in the bomb bay. Despite this, the B-52F was overshadowed by the B-52D in the conventional bombing role in Southeast Asia, so most were returned to strategic duties, including as Hound Dog missile carriers. The last B-52F was withdrawn from service in December 1978.

B-52G: ‘Super B-52’

Boeing originally began work on a ‘Super B-52’ as an alternative to the supersonic B-58 Hustler, but the resultant B-52G would prove much more long-lived. The B-52G was designed around an all-new wing and was once intended to be powered by eight non-afterburning versions of the Pratt & Whitney J75 as used in the F-105 and F-106. In any event, the B-52G retained the J57-P-43WA, although increased water capacity was provided for a longer-duration takeoff boost.

Other refinements included a program of weight-saving measures, further improving overall performance. The new wing also contained additional fuel capacity, allowing the external wing tanks to be replaced by smaller and lighter examples. The most obvious visual change affected the tail, which was now reduced in height by 91 inches. Meanwhile, the defensive gunner was relocated from their position in the tail to the main cockpit, seated alongside the electronic warfare officer.

Ultimately, the lighter structure of the B-52G and its increased fuel capacity led to structural problems and a new wing box beam had to be retrofitted, work also addressing the earlier B-52Hs, which were similarly affected.

With 193 examples built, the B-52G was the most numerous BUFF version, all of them being completed in Wichita. Service entry was with the 5th Bomb Wing at Castle Air Force Base in February 1959.

The demands of the Vietnam War saw B-52Gs pressed into service as conventional bombers, although in 1970 this version was chosen to receive AGM-69 Short-Range Attack Missiles (SRAM) to supersede the Hound Dog. You can read all about how B-52s would have employed this weapon in this previous story.

Another major in-service upgrade added the AN/AQS-151 Electro-optical Viewing System (EVS) with sensors in nose fairings that provided an improved view for the crew during low-level flight at night.

Before the end of the B-52G’s career, it had traded the SRAM for the much more flexible AGM-86B Air-Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM), 12 of which could be carried on external pylons, while part of the force later added the AGM-86C Conventional Air-Launched Cruise Missile (CALCM), which it used in combat over Iraq during Operation Desert Storm.

Retirement of the B-52G began in 1989 and was finally completed in May 1994.

B-52H: Ultimate BUFF

The only Stratofortress variant still in service, the B-52H emerged as a derivative of the B-52G, with the same basic airframe, but allied with new Pratt & Whitney TF33 turbofan engines. All H-models were built in Wichita, the plant producing 102. Another change, compared to the B-52G, was a new tail turret, armed with a single M61A1 Vulcan 20-mm rotary cannon.

The first B-52H flew in July 1960 and deliveries began in May 1961, initially to the 379th Bombardment Wing at Wurtsmith Air Force Base, Michigan.

Another planned difference was to have addressed the B-52H’s main armament, but the GAM-87 Skybolt air-launched ballistic missile was canceled, leaving the two underwing pylons for different stores.

A low-level-optimized avionics suite was incorporated from the 19th production aircraft, including Advanced Capability Radar (ACR) with terrain-following function.

Thereafter, the B-52H, like other BUFF variants, has been successively upgraded, with some of the most significant recent efforts having been undertaken to expand the type’s weapons options. After all, until the end of the Cold War, the B-52H was committed almost exclusively to the nuclear role.

Beginning with the Conventional Enhancement Modification in 1994, the B-52H had its conventional weapons options increased, ultimately adding various precision-guided munitions including laser-guided bombs and Joint Direct Attack Munitions (JDAM).

It was thanks to its new and expanding conventional arsenal that the B-52H could first go to war, in September 1996, when the type launched CALCMs against Iraqi targets. That began a long-running campaign of combat operations in both the Middle East and Afghanistan, during which the B-52H excelled in a close air support role that couldn’t have been more different from the airborne nuclear alert mission in which the type had begun its service.

Yet more modifications are now planned, including long-awaited new engines, as well as an AESA radar, a partial glass cockpit, and major enhancements to its communications and defensive suites. It’s possible that all these upgrades could lead to another new BUFF designation. That could be the B-52J, although previous concepts for a standoff jammer version of the B-52 casually used it as an unofficial designation.

In the meantime, however, with the future of the B-52 seemingly secure until at least 2050, the variety of weapons that it can carry is only going to increase. Chief among these is a new breed of hypersonic weapons, for which the Stratofortress has been identified as the ideal launch platform. Already, the B-52H is being used to test experimental examples of these weapons, with operational versions of some looking set to provide yet another new lease of life for the extraordinary bomber.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com