During the Cold War, it seemed that nuclear warheads were the solution to an alarming number of tactic and strategic challenges. Need to intercept and shoot down formations of nuclear bombers emerging from over the North Pole? Nuclear weapons. Need to sink a naval task force? Nuclear weapons. Need to get your bombers to their targets deep inside enemy territory without being shot down by enemy air defenses? Nuclear weapons, and in this case, Boeing’s AGM-69 Short Range Attack Missile (SRAM), in particular.

Much of this was more to do with limitations of precision guidance and fine-tuned targeting capabilities than anything else. A nuclear warhead has effects that can destroy soft and some fortified targets from the shockwave alone. So, acceptable and effective accuracy could be measured in hundreds or even thousands of feet, not tens of feet or even less as is common today.

SRAM was born in the early 1960s out of the glaring reality that even with nap-of-the-earth flying, America’s bombers were increasingly vulnerable to the Soviet’s ever more capable air defenses. In fact, the requirement for a nuclear-tipped missile capable of taking out enemy air defense sites that could threaten a strategic bomber on its path to its assigned target was already realized in the form of the AGM-28 Hound Dog missile.

This system entered service in 1960, but it was massive—weighing in at over 10,000lbs and measuring 42 feet long—drastically limiting what type of aircraft could employ it and how many an aircraft could carry at a single time. A better solution was needed for the Air Force to continue to claim its bomber arm of the nuclear triad represented a reliable deterrent.

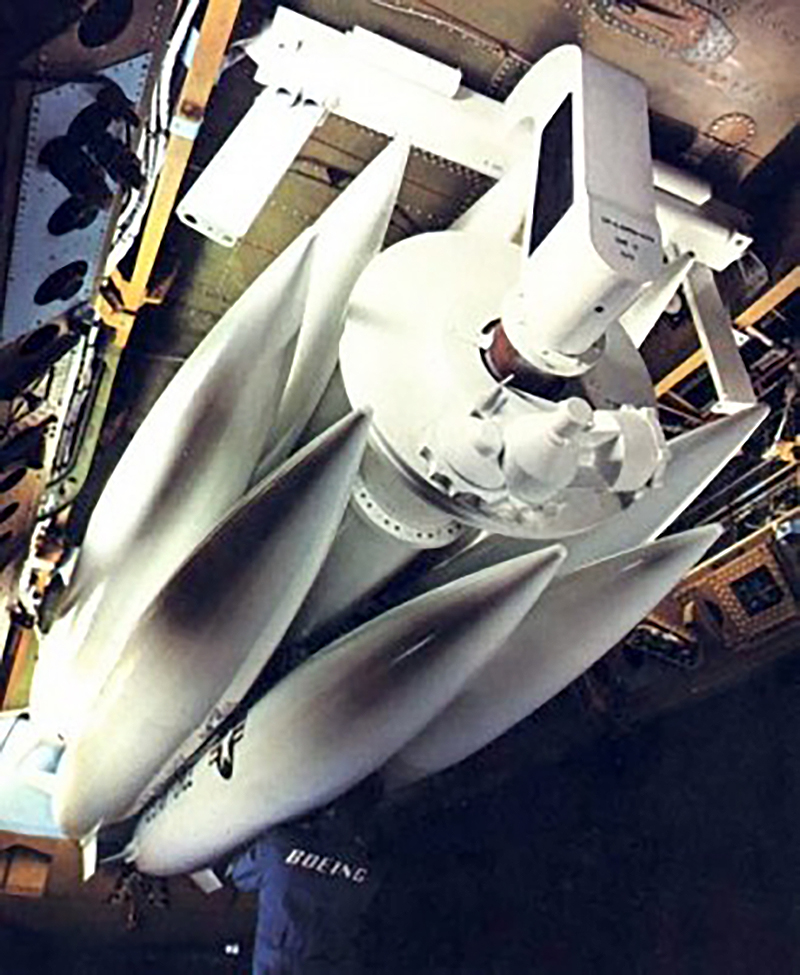

Enter the AGM-69A SRAM. Entering service in 1972, it weighed in at around 2,200lbs and measured 14 feet in length. It was minuscule compared to the Hound Dog, allowing for large quantities to be stored inside a bomber’s weapons bay. Its primary mission was the destruction of enemy air defenses (DEAD)—to obliterate threatening SAM sites along a bomber’s path—but it was also to be used as a nuclear strike weapon. In this ancillary role, it could vaporize secondary targets as its mothership flew to its primary target set.

SRAM’s range was roughly 50 miles, but could reach out to nearly 100 miles under certain flight profiles. It achieved this using a dual-pulse rocket motor that made it possible for the missile to hit targets behind the launching aircraft and achieve fly-out speeds of up to Mach 3.5. It also had a basic terrain-following feature to add to its own survivability.

Guidance was provided by an onboard inertial navigation unit giving the weapon good enough accuracy—with a circular error probability (CEP) of around 1,400 feet—to deliver its variable yield W69 warhead that could be set from 17kt to 210kt. For comparison, the “Little Boy” nuclear bomb dropped on Hiroshima had a yield of roughly 15kt. The missile was programmed before a mission with its intended target, but it could be reprogrammed in flight as well.

Originally intended for the B-52G and B-52H, SRAM went on to equip the FB-111 and the B-1B. The B-52s could carry up to 20 on its external pylons and in its internal bay. The FB-111 could carry six—two internally and four externally. The B-1B could carry two dozen SRAM—eight each on its three internal rotary launchers.

In reality, a mix of SRAMs and nuclear bombs were to be carried depending on the mission and intended target set. SRAMs would be used by the bombers to blast their way to their primary targets or, later on, to hit strategic targets that were not air defense related at all. This secondary use was especially attractive for vaporizing targets in extremely well-defended airspace.

SRAM was really an amazing invention and one that had a real purpose—helping to keep non-stealthy bombers viable for decades as Soviet air defenses matured. But, in 1982, the introduction of the AGM-86B nuclear-tipped variant of the Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM) would allow B-52s—and eventually B-1Bs—to launch nuclear strikes at long standoff ranges, placing them far from threatening air defense sites. Then, with the Cold War winding down towards the end of the decade, the need for SRAM degraded further.

In 1990, then Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney ordered SRAMs taken off all alert bombers. Concerns regarding the warhead’s ability to withstand fires aboard aircraft had become a serious issue. The W69 warheads were not built to the same standards as later designs and a ground fire on an alert bomber that occurred years earlier could have resulted in a massive release of radiation, potentially on a larger scale than Chernobyl, from the flames compromising the shielding around the warhead’s plutonium core if the winds had been blowing in a different direction.

In 1993, the aging stockpile of missiles became an even more pressing concern. Beyond the safety of their warheads, the condition of the SRAM inventory’s rocket motors was called into question. A number of SRAMs were found with cracked propellant sections, likely the result of constant changes in atmospheric temperature over the years. If fired, a cracked motor would likely explode and take the aircraft with it while also scattering nuclear debris and radiation over a huge area. This, along with major reductions in defense spending and America’s nuclear posture, were the final nail in the coffin for SRAM. The weapons were pulled from service in 1993 and destroyed.

In the end, roughly 1,500 SRAMs were built, with production ending in 1975. Over the years, a follow-on AGM-69B SRAM was proposed, including one configuration with an upgraded propulsion section and W80 warhead. Other variants that never made it beyond the drawing board included a SRAM outfitted with an anti-radiation seeker to home in on hostile radar sites without programming a specific location into the weapon prior to launch. This weapon was far more reactionary in nature that the AGM-69A and could have effectively deal with ‘pop-up’ threats, but it never came to be. An air-to-air variant was also examined.

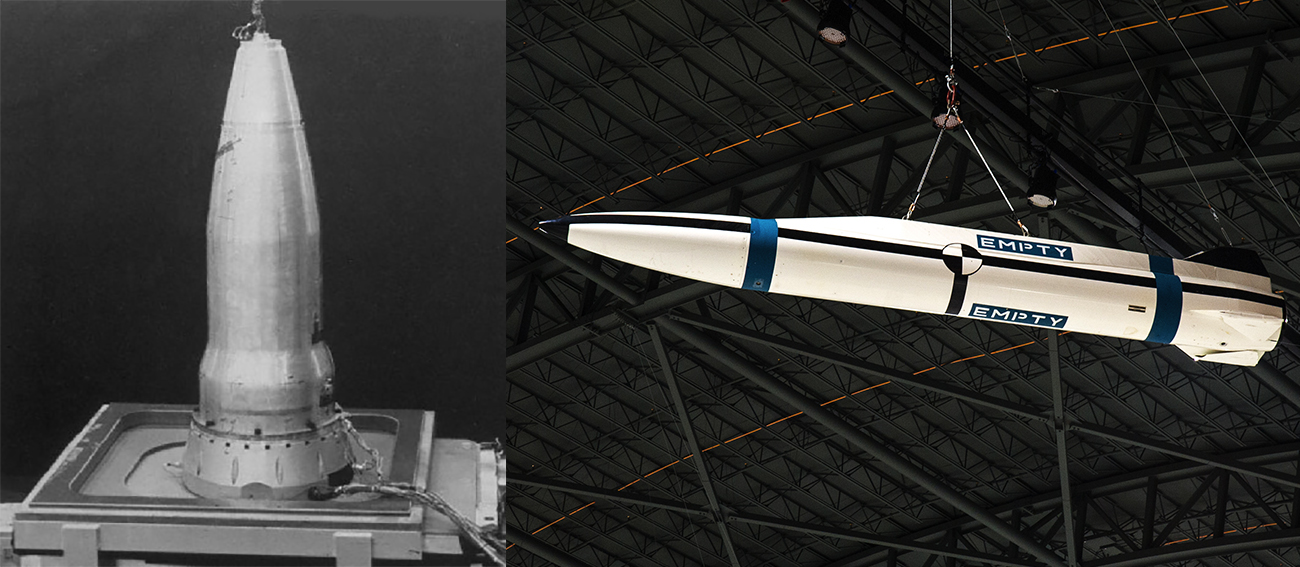

A far more robust effort began in the late 1970s to replace SRAM with an upgraded version for the B-1A bomber. When the B-1A was canceled, so was the follow-on SRAM, but once the B-1 was resurrected in B-1B form under the Reagan Administration, development for a new SRAM began again, as well. Dubbed the AGM-131A SRAM II, this weapon was largely a fresh design that featured a new and improved dual-pulse rocket motor. It was also lighter, less complex, and used a purpose-built and more modern W89 nuclear warhead as a payload.

The program progressed up until 1991. With the fall of the Soviet Union, justifying such a weapon and its costs just wasn’t possible, especially after a number of costly delays in the weapon’s development. The B-1B would lose its nuclear mission in the same decade, underscoring the logic of the decision to end the SRAM II program. In addition, cruise missiles were becoming the delivery method of choice for nuclear bombers and the level of precision of modern air-to-ground weaponry was rapidly increasing, allowing for conventional warheads to take the place of nuclear ones for many applications.

Fast forward to today and the SRAM concept is being reborn to a certain degree—albeit not in a nuclear fashion—with the development of standoff missiles uniquely designed to quickly blast enemy air defenses as fighters and bombers press toward their targets. The Advanced Anti-Radiation Guided Missile-Extended Range (AARGM-ER) is now a Navy and Air Force program and will serve as the basis for the USAF’s Stand-In Attack Weapon. Both of these missiles will be capable of internal storage on the F-35A and F-35C. You can bet they will also wind up on the B-21 Raider in the coming decade.

Above all else, the big takeaway here is that USAF bombers were very much set to fight their way to their primary target sets by blasting air defense sites with nuclear weapons along the way. As such, SRAM was a very ineloquent solution to a very real problem facing America’s airborne strategic deterrent before the introduction of highly capable air-launched cruise missiles. SRAM also serves a reminder of just how much destruction a B-52 of the latter Cold War era would have laid down in its wake.

A frightening reality to contemplate indeed.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com