There are some stories that when you come across them, touch off a storm of cognitive dissonance because they seem so antithetical to what you know. One such reaction developed in my mind as I was scanning articles in the December 1960 issue of Naval Aviation News and was struck by this uncanny headline:

“MAD Search of Salt Lake Locates a Lost Air Force Hustler.”

The dissonance I suffered stems from a few facts:

I was an operator of the Magnetic Anomaly Detection (MAD) system in the US Navy’s S-3 Viking, a sensor system designed to aid in the tracking and attack of a submerged submarine.

I grew up on the Strategic Air Command (SAC) base where the B-58 Hustler was built, evaluated, and flown operationally; however, I arrived at the base a year after the B-58 was removed from service.

As a child of a US Air Force officer, I was well-versed in the long-standing conflict between the Air Force and the Navy.

Because of these experiences, I had a difficult time processing the content of this intriguing, complex, and almost contradictory headline. How did a B-58 end up in the Great Salt Lake? How was a MAD search conducted when the Air Force didn’t have any aircraft that utilize a magnetic detection system (this was, after all, a brief article in Naval Aviation News)? What naval aircraft were called upon to perform the search? Why would the Air Force ask the Navy to search for one of its most cutting-edge aircraft, in light of the age-old rivalry between the services?

The Crash

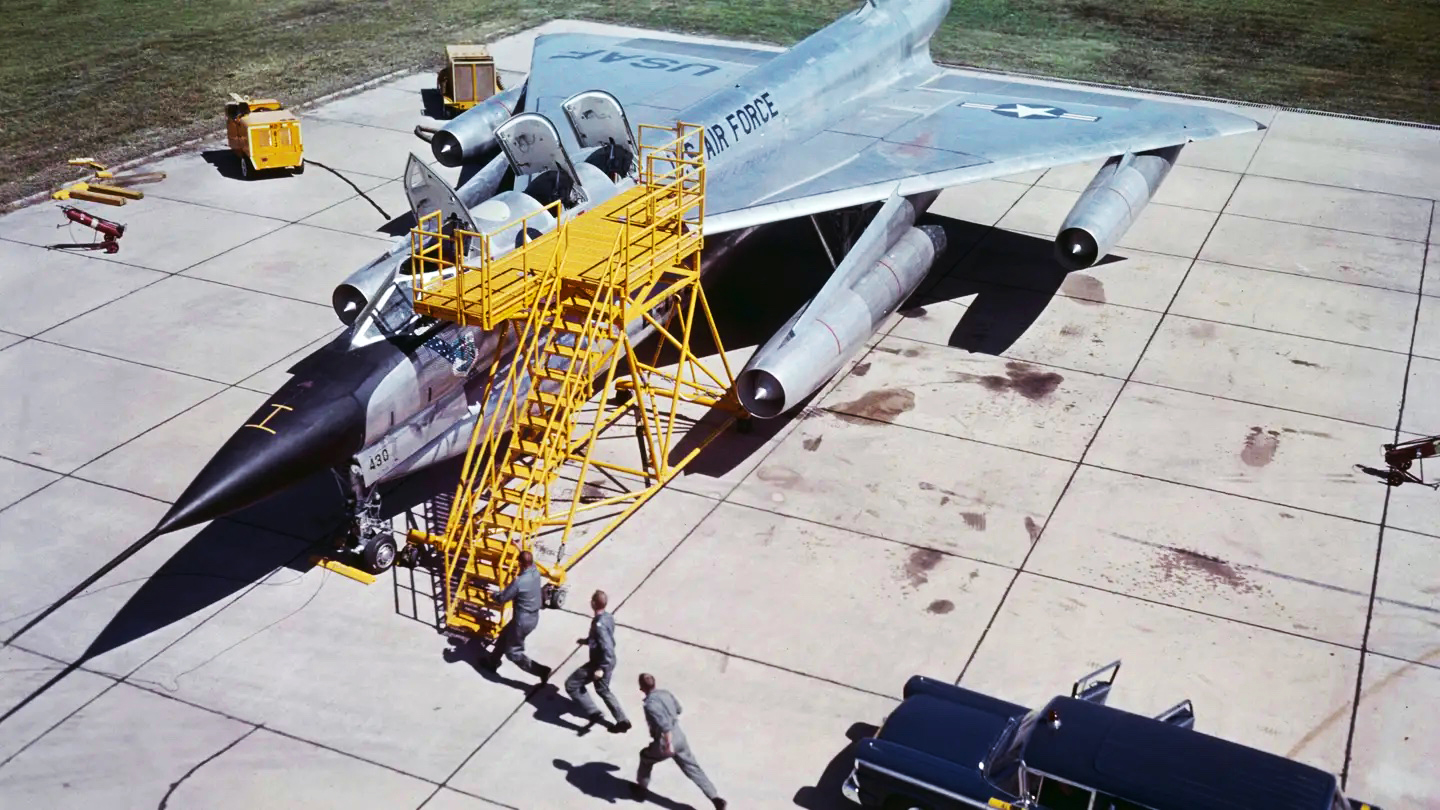

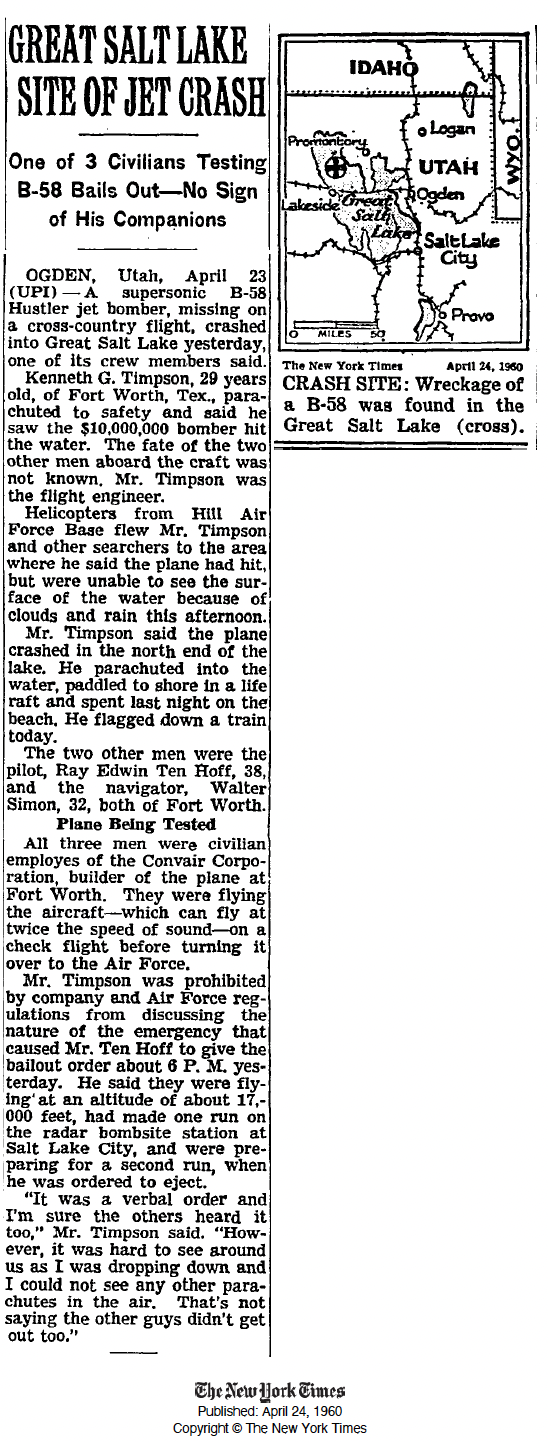

A Convair RB-58A Hustler — a version of the supersonic bomber intended to carry a reconnaissance pod below the fuselage — assigned to the Air Research and Development Command’s 6592nd Test Squadron stationed at Carswell Air Force Base in Fort Worth, Texas, launched on a mission with a civilian crew of three. Aircraft 58-1023, the thirtieth Hustler produced, was piloted by Ray Tenhoff, 38, while test engineer Walter Simon, 32, navigated from the center crew position. Another test engineer, Kenneth Timpson, 29, rounded out the souls on board flying in the DSO, or Defensive System Operator’s position. All three crewmen were employees of Convair and were taking the Hustler on a final evaluation flight before it was formally handed over to the Air Force.

In the early evening of April 22, 1960, the aircraft crashed into the northern end of the Great Salt Lake. Only the DSO survived.

The Revolution

The state-of-the-art B-58 Hustler was an exciting, provocative design. The New York Times tells of its origin in the July 2, 2011 obituary of its chief designer:

“The day the legendary test pilot Chuck Yeager shattered the sound barrier in 1947, Robert H. Widmer marched into his boss’s office at the Consolidated Vultee Aircraft Corporation in Fort Worth to say he wanted to design the world’s first supersonic bomber. He was told to stick to the contracts the company was already fulfilling.”

“Mr. Widmer, an aeronautical engineer, nonetheless threw himself into designing the plane on his own time. Two years later, when the Air Force asked for bids to build a bomber that could fly at extreme altitudes and supersonic speeds, he had all but finished.”

“Convair, as the company was called, won the contract for the bomber, the B-58, with Mr. Widmer’s design. He named the plane the Hustler. Able to fly as high as 15 miles and at a speed twice the speed of sound, it carried some of the most sophisticated military systems yet developed. The Russians had nothing that came close. Bomber pilots passed up transfers with pay raises and promotions just to fly it, Popular Science reported.”

Everything about its ultramodern design screamed of speed, of the push-button and nuclear age the world was irresistibly falling into. Most importantly, it spoke of the audacity of airpower fresh from its dominant role in the relatively recent world war.

Throughout its operational history, the Hustler was blamed for constantly challenging its crews. This was attributed to the complexity of its systems and the performance of this big, supersonic, delta-winged aircraft. “It was, in its day, the hottest flying machine in the sky. And it was the most challenging craft to fly safely and effectively… Every flight was a thrill and seldom without excitement or real danger,” wrote Phil Rowe, a Defensive System Operator, in his book B-58 Supersonic Strategic Bomber: Stories & Remembrance of a Crewmember.

Col. Rowe takes on this complexity in a description of his duties as the DSO. During mission brief the day before a flight, elevon (combined aileron and elevators) settings were determined “for each condition of gross weight, center of gravity and airspeed…” and that “CG calculations were required every hour during subsonic cruise and every fifteen minutes when supersonic.”

And yet the effort put in by the USAF to support the pilot, bombardier/navigator and DSO ensured that knowledge and experience with the airframe over time would transform the seemingly unmanageable supersonic bomber into an operationally successful weapons system.

Despite the ‘well-ahead-of-its-time’ moniker, the Hustler had a peculiar quality that Col. Rowe describes:

“The Mach 2 delta-winged wonder was, in many ways, very “high tech” for its day. But in one feature it was anything but high tech. We actually had a clothesline-type rope and pulley system running from the pilot’s front cockpit to the DSO’s [position behind], passing along the middle station of the navigator on the way. A small bag or pouch attached to the line could carry written messages from one crew member to another… but it was installed for another purpose entirely… to independently decode radio received Go Codes which might send us off to war…”

Sadly, the B-58 could not keep up with the magnitude of turbulent changes that were occurring in the aerospace arms race that developed solutions, counter-solutions, and counter-counter solutions to the rapidly emerging nuclear weapons delivery threat between the ever-competitive Soviet Union and the United States.

Nor could the Hustler outrun the prohibitive $3-billion price tag for 118 aircraft and Defense Secretary Robert McNamara’s Cost-Benefit Analysis axis. Despite the noble internal efforts of some in the USAF, the Hustler’s life came to an end.

When we think of the B-52, the F-16, or the F-15 — aircraft flying well beyond their life expectancy, it is a hard pill to swallow knowing that such a remarkable, majestic aircraft like the Hustler was operational for a mere decade.

Ask The Navy

Since the beginning of powered human flight, the U.S. Air Force and the Navy have been at odds with one another over who should control the country’s military aviation component. After World War II, when the Air Force divorced the Army, the conflict with the Navy attained ever greater heights. However, the Air Force has never relinquished a mature understanding that need outweighs pride.

For example, during World War II, the U.S. Army Air Forces gladly gave up their long-range anti-submarine warfare (ASW) mission during the Battle of the Atlantic to the Navy to focus on strategic bombing.

Another opportunity to swallow its pride came with the loss of this B-58 in the Great Salt Lake. Knowing that the wreckage wasn’t evident on the surface or visually detectable beneath from overflying aircraft, the Air Force simply couldn’t wait for the normal process of dredging to discover the lost aircraft’s precise location.

During the war, the Navy developed a device designed to detect a submerged submarine as its steel hull traveled across the Earth’s magnetic field. Known as Magnetic Anomaly Detector (MAD), a magnetometer extending from an aircraft could decipher slight variations in the regularity of the magnetic field of the planet.

In essence, the crashed Hustler had become a submarine and was lying somewhere along the bottom of the northern part of the lake in water that could be as deep as 30 or 40 feet. Thus, the Air Force called on the Navy to help find its missing aircraft.

Golden Eagles, Neptune, And MAD

Patrol Squadron Nine (VP-9), the “Golden Eagles,” was established on March 15, 1951, flying the piston-engined PB4Y-2 Privateer out of Naval Air Station Whidbey Island, Washington. In 1953, the squadron transitioned to an early version of the Neptune, the P2V-2. In 1956, while stationed in Alameda, California, the unit transitioned to the well-evolved, apex variant of the Neptune: the P2V-7 (later designated the SP-2H).

The Neptune was the aircraft of choice for this unusual mission because of its range, and endurance, and most importantly, it carried the sensor required to detect the submerged B-58.

Over the course of the Battle of the Atlantic, the P2V had been developed privately by Lockheed while observing the success of its Model 14 Hudson bomber which was used extensively by the U.K. Royal Air Force Coastal Command. The U.S. Navy was also paying close attention, but Pearl Harbor distracted them from investing in the Neptune, an aircraft intended from its initial blueprint as a patrol bomber and not an off-the-shelf airliner or cargo aircraft design. Instead, the Navy tasked Lockheed with improving the Hudson design resulting in the PV-1 Ventura and PV-2 Harpoon.

In early 1943, with uncertainty surrounding who would win the war against the U-boat, the Navy finally gave in and ordered two prototypes of the Neptune. The role of the aircraft in maritime patrol and, specifically, anti-submarine warfare was solidified by the end of 1943. The investment in the Neptune would see the production of over 1,100 aircraft, in seven primary variants, flying with 11 countries.

Making The Neptune MAD

Surprisingly, despite the World War II and early Cold War success of MAD as an ASW sensor, and the evolving threat of the Soviet submarine, the detector didn’t find itself mounted on the accomplished P2V until the fifth primary variant: the P2V-5, and then only for evaluation.

What was learned from the “Dash Five” was fully implemented in 1958 into the final production version of the Neptune. “With nearly three times the amount of equipment carried on the P2V-1 and twice the power, the Dash Seven clearly illustrated the great strides in Neptune development in less than a decade,” writes Wayne Mutza in Lockheed P2V Neptune: An Illustrated History, the definitive work on the aircraft.

Although the Dash Seven initially came off the Lockheed line with a nose, dorsal and tail turret, they were eventually removed in response to the portentous arrival of the air-independent nuclear submarine and the diesel submarine’s almost exclusive use of the snorkel. The tail of the aircraft now housed the AN/ASQ-8 Magnetic Anomaly Detection boom, and the nose featured a clear dome for the all-important observer who also operated the MAD.

Hunting A Hustler

LCDR H. R. “Pete” Johnson and his crew flew their “Golden Eagles” P2V-7 roughly 700 miles from Naval Air Station Alameda to Great Salt Lake and began to sweep for the lost B-58.

Kenneth Timpson, the only survivor, informed authorities that the aircraft had gone down at the northern end of the lake but the inclement weather prevented him from seeing the precise location of the Hustler’s impact.

Timpson told the New York Times that they “were flying at 17,000 feet… had made one run on the radar bombsite station at Salt Lake City, and were preparing for a second run, when he was ordered to eject.” At the time, the DSO didn’t know if his other two crew members had ejected. After landing in the water, Timpson boarded his single-man life raft and made his way to the nearest land. He then spent the night on the shoreline, flagging down a passing train the next day.

At this early point in the B-58’s career, the aircraft was still fitted with conventional, individual ejection seats for each of the three crew members. Later on, in an effort to improve survivability, especially at high speeds, the Hustler was retrofitted with a capsule ejection system, intended to be used safely at altitudes as high as 70,000 feet and at twice the speed of sound.

Contemporary video showing tests of the B-58’s capsule ejection system, which also made use of a live black bear as a test specimen:

The Air Force investigation, with Timpson’s invaluable help, determined that the pilot, Ray Tenhoff, lost control of the aircraft due to a failure of the Mach/Air Data System (ADS). The B-58 flight manual describes the vital ADS as a system:

“…which provides aerodynamic intelligence to various control systems. The ADS consists basically of an electromechanical air data computer which processes raw data from the pitot-static probe and a temperature sensor probe located on the left side of the fuselage above the nosewheel well. The computer utilizes the following raw data: static pressure, pitot pressure, and total temperature. When this data reaches the computer, it is transformed into electrical signal outputs through an arrangement of transducers, mechanical linkage, and servo repeaters. These outputs, when delivered to various control systems on the airplane, correspond to values of Mach number, static pressure, pressure altitude, density ratio, true airspeed, and free stream temperature. The mechanism of the computer operates at 115-volt AC power.”

Upon reaching the northern end of the Great Salt Lake, the P2V-7 began a standard MAD search and discovered the primary wreckage, submerged in 40 feet of water.

Epilogue: “Erasing Four Decades of Regret, and Remembering a Friend”

While gathering information about the loss of this B-58, I came across an unexpected element that added a deep measure of flesh to the bones of this remarkable story.

Jay Miller, who was 12 years old at the time of the crash, tells of his wide-eyed admiration and familial connection with the Hustler pilot. In the fall of 2000, he received the following voicemail:

“‘If this is the Jay Miller who was Ray Tenhoff’s friend, would you please call me?’ … Thus began — unknowingly for me at that moment — a closure that I had considered unattainable for just over 40 years. Four decades of regret were about to be erased absolutely and unequivocally by the kindness of a person I had never known.”

You can read the rest of Jay’s story here.

As for what happened to the B-58 in the Great Salt Lake, that remains a puzzle. Air Force sources don’t reveal whether some or all of the Hustler’s wreckage was recovered and, at the time, these details were highly classified. Bearing in mind that the aircraft was still very new, and a highly expensive asset, it would seem likely that they would want to retrieve as much they could of it for a thorough investigation. If anyone out there knows more about what happened to the B-58, we would love to hear from them.

Contact the editor: Thomas@thedrive.com