For most of its career with the U.S. Air Force, the FB-111A, Strategic Air Command’s version of the F-111 Aardvark, was pretty much unloved. After a troubled path to service, the tactical F-111 eventually became one of the most capable strike aircraft of the Cold War, while the FB-111 fulfilled a requirement for a supplemental bomber to augment Strategic Air Command, only 76 examples being built to provide a stopgap until a next-generation bomber became available. However, with the cancelation of the original B-1 bomber program in 1977, another opportunity suddenly emerged for the FB-111, or a derivative thereof, to shine. To take the place of the larger, more advanced bomber, the Air Force started looking at a much-improved “Super FB-111,” and the idea lingered on until the B-1 program was finally revived under the Reagan Administration in 1981, resulting in today’s B-1B Lancer.

General Dynamics, the FB-111A’s manufacturer, had already begun studies to enhance the aircraft in 1974, hoping to address the limited range and payload that dogged an aircraft that hadn’t originally been designed for the strategic mission and which Strategic Air Command found itself operating more or less against its will.

Development of a reworked, stretched-fuselage version of the FB-111A, eventually known as the FB-111H, initially took place secretly within General Dynamics, since the U.S. Department of Defense remained committed to the more ambitious B-1. The firm invested almost $10 million of discretionary funds on the studies, including 800 hours spent evaluating wind-tunnel models, plus completion of a quarter-scale model used to assess the radar cross-section at its Fort Worth, Texas, plant.

President Jimmy Carter had different plans for the B-1, which he canceled in June 1977, describing it as “a very expensive weapon” that was “not now necessary” because of the “recent evolution of the cruise missile.” For a brief moment, at least, the concept of a penetrating bomber — one that relied primarily on speed to get to its target, rather than lobbing cruise missiles from a safe standoff distance — was dead.

Just two-and-a-half months after the ax fell on the B-1, the House Appropriations Committee began to look at alternatives to the stillborn B-1. These included simply resuming work on the B-1, developing an all-new B-X penetrating bomber, a rebuilt and upgraded B-52X penetrating bomber design, adapting B-52s into more capable cruise missile carriers, converting commercial or military widebody aircraft into launch platforms for cruise missiles, and the FB-111H. Also, among all these options, the Carter administration was also secretly pushing ahead with stealth technology, including the Advanced Technology Bomber and F-117 Nighthawk, some of the early history of which you can read about here.

Although the House of Representatives still preferred the B-1, in September 1977 the Senate Armed Services Committee recommended a $20-million budget for Fiscal Year 1978 to study the FB-111H. The argument was that this aircraft would be able to match the B-1 in almost every aspect of performance, apart from its weapons payload, which would be roughly half that of the larger bomber.

It was envisaged that the first FB-111H could be converted from an FB-111A and take to the air within two years, followed by a second prototype six months later.

General Dynamics subsequently developed a test plan for these two aircraft. It was planned to use the first to evaluate propulsion, performance, stability and control, flutter, flight load, and stores separation. The second would be utilized for tests of the electronic countermeasures system, terrain-following radar, and the navigation/bombing system.

Then, once these two airframes had been successfully proven, another 65 examples would be converted from other FB-111As, before General Dynamics would reopen the production line to produce another 100 new-build versions.

This 167-aircraft fleet was anticipated to cost $7 billion, providing a unit price of $42.1 million, which was less than half the expected cost of each B-1A. Beyond that, there was the possibility that more FB-111Hs could be ordered beyond this total, allowing the swing-wing bomber to finally fulfill its full potential as a key component of Strategic Air Command’s fleets and potentially replacing aging B-52s as well.

While it would retain 43 percent structural commonality with the FB-111A, and 79 percent of its subsystems were to be similar to the ones found in that earlier design, the H-model was expected to look significantly different from the basic Aardvark. Its stretched fuselage would accommodate new engines, additional fuel capacity, and an enlarged weapons bay, resulting in reconfigured landing gear and entirely different air intakes, which would be fixed rather than the variable-geometry design that The War Zone has looked at in detail in the past. The F-111/FB-111’s unique crew escape module was to be retained.

The powerplant would be a pair of General Electric F101 turbofans, the same engines used in the original B-1As and the later B-1Bs, each of which was rated at 30,000 pounds of thrust at full afterburner.

The variable-geometry wings would retain the same 70-foot span when fully spread as earlier F-111 variants, but would now be able to sweep back to only 60 degrees, compared to 72.5 degrees on the FB-111A. This would eliminate the low-level supersonic “dash” capability, but the H-model was still expected to be able to hit Mach 0.95 at sea level.

Performance-wise, the FB-111H was planned to reach a speed of Mach 1.6 above 36,000 feet, a cruise speed of Mach 0.75, and a low-altitude penetration speed of Mach 0.85 flying at 200 feet. This would be slower than the FB-111A, which could hit Mach 2.2, but the tradeoff was judged acceptable to boost range and weapons carriage.

The enlarged fuselage would add another 104 inches in length, making the aircraft 88 feet 2.5 inches long compared to the FB-111A’s 73 feet 6 inches. Weights were to be increased proportionally, including an empty weight of 51,832 pounds and a maximum inflight weight of 155,000 pounds. The same figures for the FB-111A were 116,115 pounds and 122,900 pounds, respectively. To allow truly strategic range, internal fuel would have to be doubled, growing to a whopping 64,000 pounds.

It was in terms of range that the FB-111H would have offered a real advance over the FB-111A. While its predecessor could fly 5,300 nautical miles, the FB-111H would have increased this figure by 44 percent, for a range of 7,632 nautical miles. In both cases, this envisaged a mission profile that included the aid of aerial refueling, a 1,200-nautical-mile high-speed dash at low level, and carriage of two internal nuclear weapons. What is more, the FB-111H would be able to match the range of the FB-111A when carrying three times the payload.

Those weapons were to be carried in a bomb bay that was almost doubled in size, allowing four or five nuclear weapons to be carried instead of two. There would also be external hardpoints, too, 12 in all, including six that were below and on the sides of the air intakes, not dissimilar to those later found on the F-15E Strike Eagle. While the FB-111A could carry a maximum of six nuclear weapons, this revised design was expected to haul 15. These would be either freefall bombs or AGM-69 Short-Range Attack Missiles (SRAMs), the latter being a Cold War-era defense-suppression weapon that you can read more about here.

The avionics and self-defense suite for the FB-111H was expected to benefit considerably from equipment that had been developed for the B-1 and would have included an AN/APQ-144 radar, a modified AN/APQ-134 terrain-following radar, AN/APN-200 Doppler Velocity Sensor, AN/AJN-16 and SKN-2400 Inertial Navigation Systems, dual CP-2A computers, AN/ALQ-131 and AN/ALQ-137 electronic warfare jammers, AN/ALQ-153/154 tail warning radar, AN/ALR-62 radar warning receivers, and AN/ALE-28 chaff/flare dispensers.

Aside from its cost, projected performance, and, at least compared to the FB-111A, its payload, there were other factors that made the FB-111H an attractive proposition for the Air Force. Despite its mission with Strategic Air Command, the FB-111A was not classed as a strategic asset and the same would be the case for the FB-111H, preventing it from being subject to restrictions that might be imposed by future Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) agreements or similar arms control deals with the Soviet Union. In the same way that the Soviet Union argued that the Tu-22M Backfire was a non-strategic asset, the United States could have likely done the same for the FB-111H, pointing out that it was merely a derivative of the F-111/FB-111.

However, the Senate Committee’s decision to pursue the FB-111H instead of the B-1 drew the wrath of members of the House Appropriations Committee. They made the case that the Carter administration had informed them that the penetrating bomber had no future and yet now another penetrating bomber was being approved. In late October 1977, the House of Representatives overruled the FB-111H study budget that the Senate had proposed and instead fought to get the B-1 back on track.

The FB-111H, however, was not entirely dead and lawmakers agreed it could be revived at a later date if a case could be made to reassign funds.

Writing about the FB-111H at the time, Dr. Harold Brown, U.S. Secretary of Defense, noted: “Our analysis showed no significant advantage in cost or effectiveness over the B-1. That being the case, coupled with the added uncertainties of — and time required for —development, there was little purpose in pursuing an option that at best would be roughly equal to what we already have in hand. However, now that we have canceled production of the B-1, it may turn out that beginning in a few years from now it will be less expensive to maintain some version of the FB-111 as an option for an advanced penetrator than the B-1.”

Although no recommendations were made to fund the FB-111H in the fiscal years to come, by late 1979 the Air Force was revisiting the idea of a reworked FB-111, with proposed variants known as the FB-111B/C. It is not entirely clear how these proposed variants differed from each other, but it may have been a matter of alternative avionics, other minor differences in the overall designs, or the starting variants from which they were to be converted.

Regardless, this plan looked again at stretching FB-111As to accommodate more fuel and weapons and re-engining them with F-101s. The gross takeoff weight for the FB-111B variant, at least, was to be 140,000 pounds. Projected weapons loads were broadly similar to the FB-111H. It was expected that these aircraft would penetrate to the target area flying at below 200 feet and at a speed of Mach 0.85.

A total of 66 FB-111As would be converted to the new configuration under the revised proposal, which would then be joined by 89 more modified F-111Ds. Those latter aircraft would be similarly modified after their transfer from Tactical Air Command. It was estimated that the FB-111B/Cs could be operational by 1983, with all of the planned aircraft modified into these new configurations by 1985.

Since the FB-111B/C program would involve no new-build production, it was potentially cheaper than the previous FB-111H project and the Strategic Air Command leader General Richard Ellis described it as: “the best near-term solution to the penetrating bomber problem.”

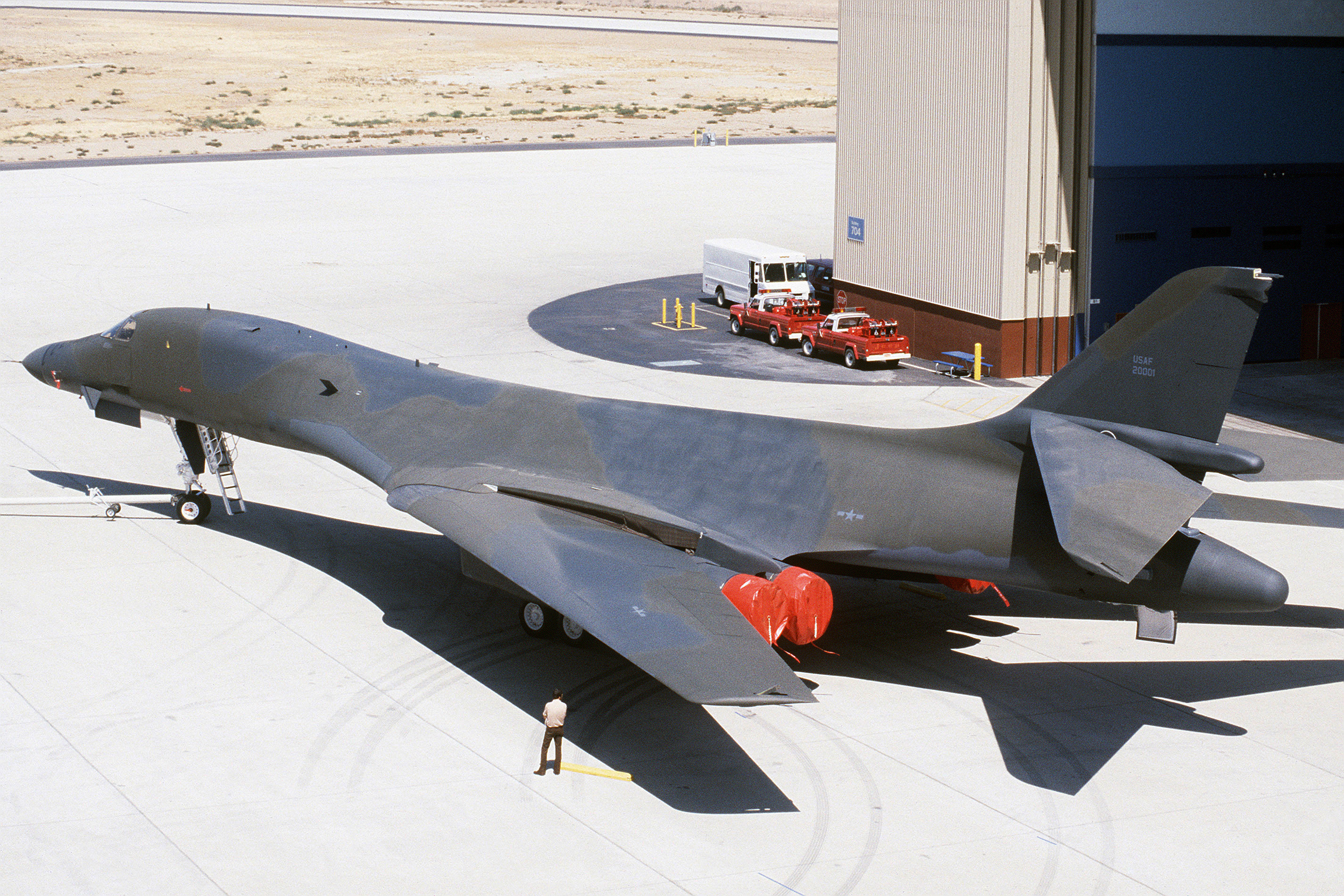

The FB-111B/C was still on the agenda in 1981, but in October of that year, the newly elected President Ronald Reagan took the bold step both to resurrect the B-1 — now as the somewhat more modest B-1B, optimized for low-level missions — as well as invest in the future B-2 stealth bomber.

The FB-111’s loss was the B-1’s gain and those latter bombers remain workhorses of the Air Force, despite repeated plans to retire them and other well-publicized problems with the fleet. Had the FB-111H — or indeed the FB-111B/C — been procured, it’s difficult to know how they would have fared long-term, although they would not have been able to match B-1B’s much-vaunted ability to carry conventional weapons, and huge numbers of them.

Putting aside the smaller payload, the improved variants of the FB-111 could have been relatively low-cost, plentiful assets that might even still have been around to undertake the kinds of long-range force-projection missions that the B-1B regularly flies today, or even received a conventional role post-Cold War. An aircraft with that kind of ‘regional bomber’ unrefueled range and large payload could have proven very useful in the post-Cold War age.

As it is, the FB-111 in general is destined to be remembered as a Cold War bomber that never quite cemented its place in the Air Force’s strategic branch.

Editor’s note: A big thanks to WB Young (@FormerDirtDart) for the inspiration on this one!

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com