Nearly four decades ago, a U.S. Air Force B-52H bomber, armed with eight nuclear-tipped AGM-69A Short Range Attack Missiles and four B28 nuclear gravity bombs, burned for hours at Grand Forks Air Force Base in North Dakota. Years later, despite previous assurances that the risk of a nuclear accident had been low, the director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, a key U.S. nuclear weapons research and development facility, testified that the incident had actually come very close to being “worse than Chernobyl.”

The bomber and its six-person crew, assigned to the 319th Bomb Wing, were sitting on alert status at Grand Forks on the night of Sept. 15, 1980. The aircraft’s number five engine burst into flames during an engine start at around 9:00 PM local time. The crew immediately evacuated the aircraft and firefighters ultimately battled the blaze for three hours before getting it under control.

Winds were high that night, blowing to the southwest with gusts registering between 26 and 35 miles per hour. The blasts of air kept the massive cone of flame from the burning engine blowing forward of the aircraft. In the end, three firefighters suffered minor injuries and another one, along with a member of the bomber’s crew, received treatment for smoke inhalation after the accident.

A subsequent investigation found that maintenance personnel had improperly reassembled a fuel strainer, which exists in the aircraft’s fuel system to catch any particulate matter before it enters the engine, which could potentially cause damage of its own. The result was additional fuel flowing into the engine, leading to the fire. The nature of the fuel leak contributed to the difficulty in putting out the fire, as the number three wing tank in the fully fueled bomber kept feeding the flames.

Between 1969 and 1991, the Air Force kept some number of B-52 bombers armed with nuclear weapons on alert at all times to try to ensure that they could rapidly get airborne and escape any potential first strike on their operating bases and then be available to retaliate. You can read more about this doctrine in this past War Zone piece. This alert posture on the ground had replaced a previous policy of keeping a force nuclear-armed bombers airborne at all times, known as Operation Chrome Dome, which ran from 1960 to 1968.

The bomber’s loadout was standard for the time and the two different types of weapons would have served complimentary purposes during any actual mission. By the 1960s, it was already increasingly clear that B-52s would have trouble penetrating dense hostile air defenses, such as those in the Soviet Union, in order to get to their assigned targets.

Starting in 1972, the bombers began carrying the AGM-69A Short Range Attack Missiles or SRAMs, with plans to fire them at enemy air defense sites along the route to their primary objectives. Each one carried a W69 thermonuclear warhead, with an estimated yield of between 170 and 200 kilotons. The aircraft would then drop traditional nuclear gravity bombs, such as the B28s, variants of which had estimated yields up to 1.45 megatons, on their main targets. You can read more about this doctrine and the SRAMs themselves in this past War Zone piece.

At the time of the accident, the Air Force informed the public that there had been little danger of either the SRAMs or the B28 bombs detonating in a thermonuclear explosion. With no fatalities or serious injuries and the damage largely limited to the bomber itself, the incident quickly passed from the public’s consciousness.

“There have been thousands of accidents involving U.S. nuclear weapons. In most cases, we can thank good engineering or smart personnel decisions for keeping things from becoming catastrophic,” Stephen Schwartz, a nonresident fellow at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and an expert on American nuclear weapons programs, told The War Zone. “In the case of the September 1980 B-52 fire at Grand Forks AFB, it was sheer luck that kept an engine fire from leading utter disaster.”

In 1988, Dr. Roger Batzel, then-director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, or LLNL, in California, testified before the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense in a closed session. A redacted transcript subsequently became available to the public.

“You are talking about something that in one respect could be probably worse than Chernobyl,” Batzel told the subcommittee members. Two years earlier, an explosion and subsequent meltdown at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in what was then Soviet Ukraine led to what experts still consider the worst nuclear disaster in human history. The full scope and scale of that incident, the subject of a recent and immensely popular HBO miniseries, would not become public knowledge for many years after LLNL’s director made the comparison in his remarks to American legislators. An exclusion zone remains in place in present-day Ukraine around the plant.

“Do you know that through testing?” Dennis DeConcini, then-Democrat Senator from Arizona, asked Batzel. “Yes, sir,” Batzel replied.

Batzel informed the subcommittee that if the wind had been blowing in almost any other direction, then the intense fire would have likely incinerated the aircraft and the weapons inside its bomb bays. The plane’s crew would likely not have survived either. This is almost exactly what happened in January 1983, when another fire completely destroyed a B-52G bomber at Grand Forks, killing five maintenance personnel. Thankfully that plane was not carrying nuclear weapons at the time.

If this had happened in the 1980 accident, the rocket motors in the SRAMs, as well as the conventional explosives inside their W69 warheads, used to initiate the thermonuclear reaction, would very likely have exploded. While this may not have triggered a nuclear explosion, it would have thrown a plume of highly radioactive plutonium into the air, easily covering a 60 square mile area, which would have included parts of North Dakota and Minnesota.

As many as 70,000 people living within 20 miles of Grand Forks could have been exposed to high doses of radiation. Depending on the exact circumstances and weather patterns, radioactive material may have been blown even further across communities to the southwest. The nuclear material would also have contaminated the ground and potentially gotten into water supplies causing further, long-term environmental impacts.

With the rate of decay of the plutonium from the nuclear weapons on the B-52s, affected areas would have seen elevated levels of radiation for tens of thousands of years and an extensive clean-up and disposal effort would have been required to make them habitable again. An exclusion zone, such as that around Chernobyl, might have been necessary to seal off the most seriously impacted locations.

“You have plutonium in the soil and on the soil, which you have to clean up,” Batzel said. “I wouldn`t want either one.”

Concerns about safety risks associated with the SRAMs and their W69 warheads were known as early as 1974. Senior officials within America’s nuclear enterprise had warned that the warheads, in particular, had been built with relatively loose safety requirements and lacked fire- and explosion-resistant features that had become increasingly common in U.S. nuclear weapons over the years. Testing had also called into question the safety of the rocket motors under similar conditions.

U.S. military officials had reportedly rebuffed these concerns on multiple occasions from officials from the Department of Energy, including Batzel and retired U.S. Navy Admiral James Watkins, who had become President George H.W. Bush’s Secretary of Energy in 1989. Another round of Senate hearings in 1990, plus the public disclosure of Batzel’s testimony, pushed then-Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney to finally call a meeting with Watkins, then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff U.S. Army General Colin Powell, and senior Air Force officials.

That meeting occurred on May 26, 1990. Cheney had ordered all of the SRAMs removed from B-52s sitting on alert and placed in secure storage by June 9. President Bush ended the policy of keeping the bombers on alert status entirely in 1991.

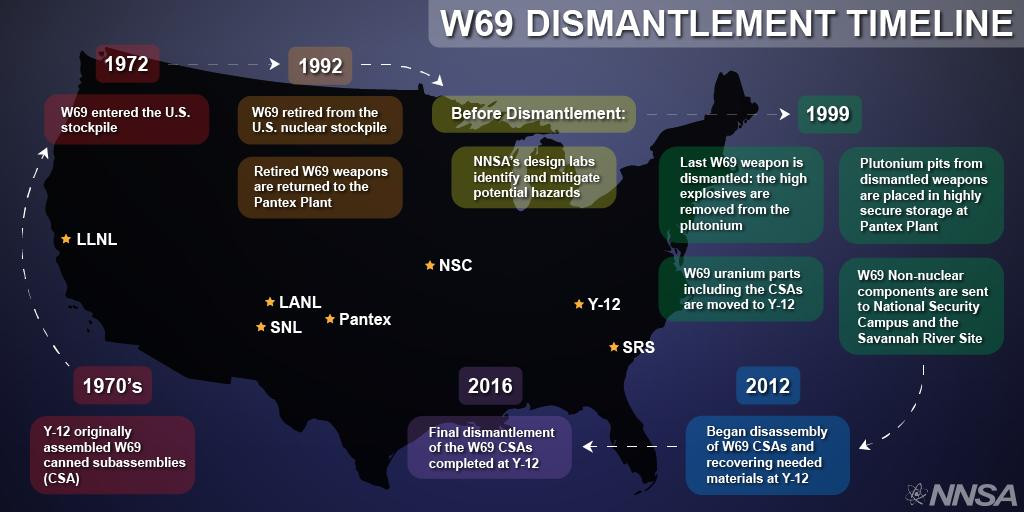

The United States began removing the weapons from its nuclear stockpile for good in 1992. The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNDA), part of the Department of Energy, completed an initial dismantlement process on all of the W69s by 1999, but did not finish completely dismantling their component parts until 2016.

The SRAMs weren’t the only risk during the accident at Grand Forks in 1980, though. “Worse still – and unmentioned by Batzel – a design flaw in the B28 bomb meant that if exposed to prolonged heat, two wires too close to the casing could short circuit, arm the bomb, trigger an accidental detonation of the HE [high explosives] surrounding the core, and set off a nuclear explosion,” Schwartz wrote on Twitter on the most recent anniversary of the accident.

The B28s remained in service until 1991. Though the process of dismantling these weapons began shortly thereafter, it is not immediately clear if the NNSA has finished breaking them down completely.

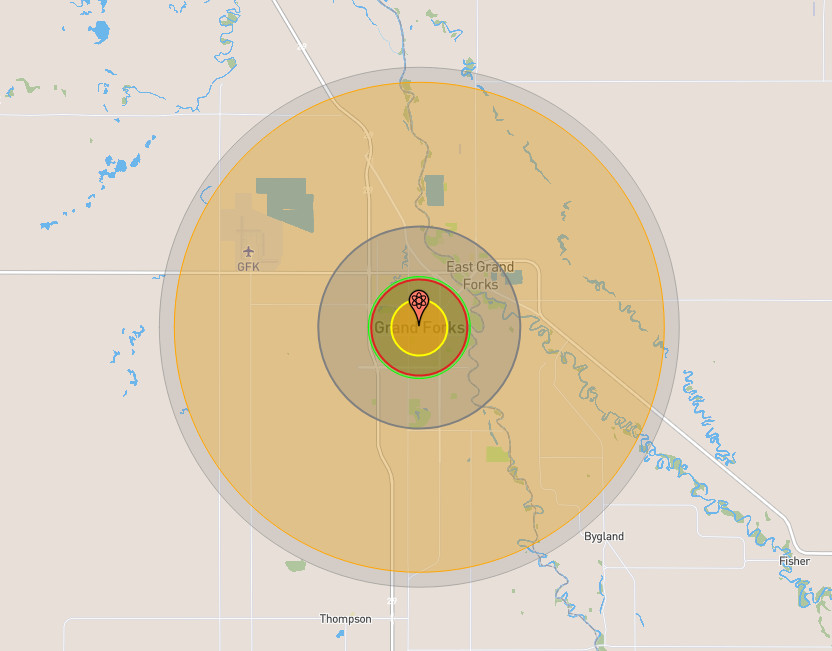

Using NUKEMAP, an interactive map that nuclear weapons historian Alex Wellerstein, a professor at Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey, first created in 2012, we can get a sense of the potential immediate damage if one or more of the B28s had gone off that night in September nearly 40 years ago. Modeling based on a single 1.45 megaton surface detonation, the fireball could have touched everything within a mile of the base. The immediate shockwave, enough to severely damage or even destroy heavily built concrete structures, would have struck anything within a mile and a half from where the bomb was sitting.

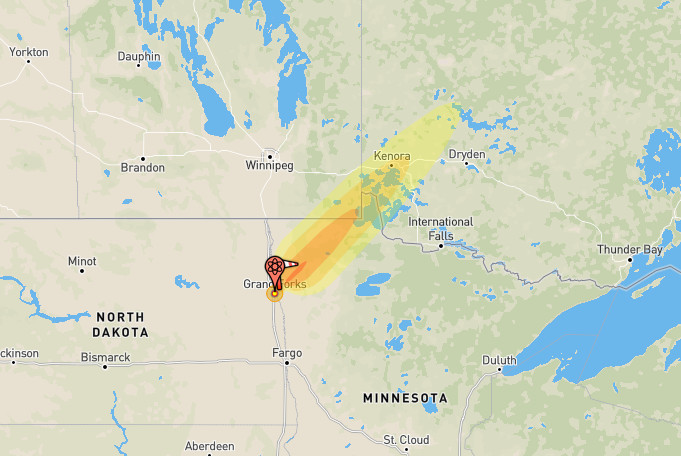

Thermal radiation could have caused severe injuries to anyone within a 16 mile-wide circle around ground zero. This is to say nothing of the effects from the resulting fallout and how it might travel on the wind. NUKEMAP’s projections, based on more recent weather conditions, suggest that the spread of radiation would have traveled more than 250 miles northeast, into Minnesota and Canada.

The southwesterly wind in 1980 would have pushed that plume in the other direction, at least initially, potentially covering a wide swath of predominantly rural farmland in North and South Dakota, potentially contaminating the Missouri River and countless farms. This could have produced farther-reaching impacts in the long term. Regardless, more than 60,000 people might have died instantly, or within days from burns or radiation, with an untold number of subsequent deaths, injuries, and long term illnesses resulting from the explosion in total.

Needless to say, it’s terrifying to think what could have happened had the wind shifted at all as the B-52’s engine burned over those three hours. It’s also a sobering reminder that while nuclear deterrence requires various U.S. Air Force units, as well as Navy ballistic missile submarines, be in a heightened state of readiness to use nuclear weapons, if need be, that this also carries significant inherent risks even just from relatively mundane accidents.

This reality has become apparent again in recent decades for a number of reasons, including concerns about morale within Air Force units tasked with nuclear missions, which in turn have raised fears about whether this increases the risk of accidents occurring. Notably, in 2007, Air Force personnel mistakenly loaded six AGM-129 Advanced Cruise Missiles, each with a W80-1 variable yield nuclear warhead, with a maximum yield estimated at 150 kilotons, onto a B-52 at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota.

The plane then flew with these weapons on board, unknown to the crew, to Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana. In the end, the aircraft was armed with live nuclear weapons for a total of 36 hours before personnel uncovered the error and instituted appropriate security and safety precautions at Barksdale.

More recently, there has been a renewed emphasis on nuclear weapons within the U.S. government and a return to thinking about how they fit into America’s overarching military doctrine, including new discussions about how American forces might employ and operate around them during actual major conflicts. This has reinvigorated debates around nuclear surety and safety – basically, the bombs will only go off when you need them to and never when you don’t, a principle America’s nuclear enterprise refers to as “always/never.”

These fears are hardly limited to the United States. Russia, especially, has been pushing ahead in the development of a number of novel and controversial nuclear weapon systems in recent years, many of which have equally unique risks associated with them. Just in August 2019, an explosion during a test of what appears to have been nuclear-powered cruise missile killed at least seven people at a Russian military test site. The full scope of the incident, including potential releases of radiation into the atmosphere, remains unclear more than a month later.

“The more nuclear weapons we have and the more we have on alert, the greater the risk of accidents. We were extremely lucky during the Cold War that no nuclear weapons ever accidentally exploded and no crises got completely out of hand,” Schwartz told The War Zone. “But human beings are fallible, as are the systems they have designed to control nuclear weapons. Accordingly, there will be more mistakes and accidents and crises in the future.”

The B-52 fire at Grand Forks in 1980 underscores just how easy it might be for a relatively simple accident to turn into a major catastrophe under the right circumstances.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com