December 2022 has been a big month for Stealth Bombers. The rollout of the B-21 Raider, the most advanced officially disclosed aircraft mankind has ever built, has captured imaginations and has spurred new interest in the future of air combat and the role stealth bomber-like platforms play in it. At the same time, the B-2 Spirit, still alien looking many decades after first being shown to the public, is entering into the golden years of its service. Some may argue that its replacement in the form of the B-21 can’t come soon enough.

Still, Northrop’s original stealth flying wing represented an absolute quantum leap in military aviation technology and remains an icon of aerospace innovation. But there was another aircraft design that competed directly with it at the time — four decades ago — as part of the highly classified Advanced Technology Bomber (ATB) program. That was Lockheed Skunk Works’ ‘Senior Peg’ stealth bomber concept.

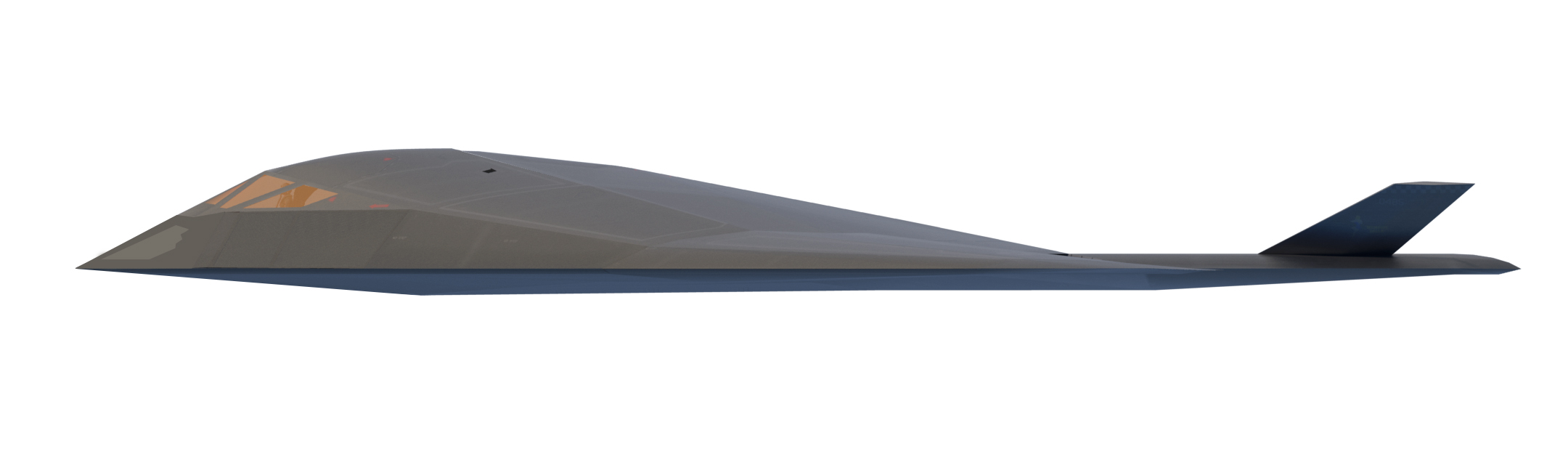

So, once again, in collaboration with master aerospace illustrator Adam Burch of Hangar-B Productions, and based on the information available, we created Senior Peg like you have never seen it before, bringing it to life as if it had won the stealth bomber race all those years ago and became an operational aircraft.

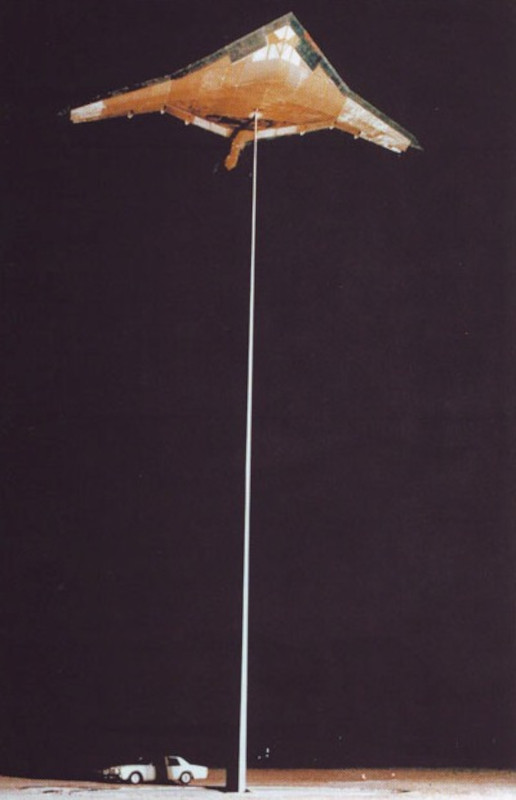

There was comparatively little information to go of — a single pole model photo in the public domain is the critical piece of information in this regard. Still, while many questions about the Skunk Works’ stealth bomber that never was still remain, the pole model image provides a fantastic amount of detail.

The model image combined with on-the-record descriptions of the aircraft and its lineage, including knowing that Have Blue and the resulting Senior Trend design that turned into the F-117 had much influence on the Senior Peg configuration, as you can read all about in our background narrative about the program following these illustrations, helped fill in some blanks. How the B-2 emerged and quickly evolved in terms of skin treatment and coatings also helped. In the end, we came up with as close a representation of what Senior Peg could have looked like as an operational aircraft as possible.

Now, after months of revisions, here are those renderings:

Senior Peg’s windscreen and intake configuration were among the most interesting facets of the design to bring to life, and the pole model seemed to show them very clearly. From the model, we extrapolated that radar wave attenuating flat mesh intake screens, as seen on the F-117, although at a unique angle along the leading edge, would have likely covered the aircraft’s large intakes. These would have fed the aircraft’s engines with air via serpentine ducts, like the F-117, to minimize radar reflectivity from the critical front aspect, especially from fire control-type radars. The exhaust would be a planar, low-observable type with passive and possibly active cooling features. Like the B-2, it would have limited direct line-of-sight of the exhaust ports from most aspects. The windscreen was also reminiscent of the F-117, with triangular and trapezoidal gold-infused panes, with the same configuration as seen on the pole model.

The radar arrays were a big question and it isn’t clear what Lockheed exactly had in mind. It’s possible that the large intakes seen on the pole model were indeed radar apertures for large bi-static arrays, but that is unlikely as the inlets would then needed to have gone underneath. It also doesn’t match the shading on the model. Extrapolating the F-117 and the pole model, the aircraft would have been fairly flat with shallow faceting underneath, which would have not been ideal for installing the radar. So we interpreted a dual-phased array setup on the upper nose’s apex — which the pole model seems to indicate — with the possibility of a pair of arrays underneath.

The exact radar configuration for the Senior Peg aircraft remains a mystery. Skunk Works’ goals for the aircraft, which focused on a smaller and more affordable design than Northrop’s Senior Ice concept, likely featured a smaller set of arrays than those that ended up on the B-2. Northrop also learned a lot from their top-secret Tacit Blue demonstrator, which heavily influenced their Senior Ice design. That very stealthy aircraft carried a massive phased array radar with low-probability of intercept ground-moving target indicator capabilities that was a part of the larger Pave Mover program and offshoots of that radar capability ended up in the B-2.

With a smaller payload and shorter range than its competition, we envisioned a single weapons bay. The wings were clearly inspired by those on the F-117, as seen on the pole model.

Accommodations would have to be made for access panels, ejection seat ports, leading-edge composite structures, communications, and aerial refueling. The lumps along the trailing edge of the wings would have concealed actuators for the aircraft’s control surfaces, as seen in the pole model.

Finally, and clearly, the most bizarre part of the Senior Peg design was its little tail. This was clearly displayed on the pole model and was directly explained by Ben Rich in his incredible memoir Skunk Works, which we will get to in a moment.

Taken as a whole, Senior Peg was one incredibly bizarre, but sinister-looking flying machine that featured some very unique silhouettes. It had some in common with the Senior Ice design that became the B-2, but it featured more of a blended-wing body than a flying wing with elements of the F-117’s faceted approach worked in. Meanwhile, Senior Ice was very much a successor to Tacit Blue and a true flying wing design, which is unsurprising considering Northrop’s previous history with the flying wing configuration under company founder and aerospace visionary Jack Northrop.

Now you can read what is known about this intriguing design’s lineage and how some of its puzzling features came to be.

Senior Peg Background

More than four decades after Northrop won the Advanced Technology Bomber competition, the available granular details about the competing design from Lockheed’s famed Skunk Works advanced projects division, and its evolution, remain relatively limited. The War Zone has reached out in the past to Skunk Works for more information about the proposed aircraft and was told that there really wasn’t anything in the company’s archives to share that isn’t out there already. As such, Senior Peg’s story remains a relatively murky one with many gaps. What we do know is provided from unique on-the-record perspectives. As such, the details may be skewed, but here is the gist of it, as far as we understand it.

What is most immediately clear is that the relationship between the F-117A Nighthawk and its predecessors and the Senior Peg bomber concept is more than simply a product of Skunk Works having developed both of them. There is a direct lineage that can be traced from the Have Blue stealth demonstrator to Senior Peg.

Have Blue had been developed in the mid-1970s as part of a Defense Advanced Research Projects (DARPA) program called Experimental Survivable Tactical, or XST. DARPA’s main objective with this effort was to acquire an advanced demonstrator aircraft designed to be very difficult to detect by radar, especially from the front and side, using passive, rather than active design features. Active measures in this context were things like electronic warfare jammers and other systems designed to actively interfere with an opponent’s radars.

Lockheed was not initially part of the XST competition, DARPA having excluded it ostensibly because the company, at that time, had not been actively involved in the development of a tactical combat aircraft for years. In addition, Skunk Works’ advanced work on stealth technologies for the A-12 Oxcart and SR-71 Blackbird supersonic spy planes was so secret that DARPA was simply not aware of it.

With prodding from Skunk Works, where the legendary Kelly Johnson was still at the helm at the time, among others, the Central Intelligence Agency gave permission for the company to share relevant information with DARPA, which ultimately led to Lockheed’s inclusion in the XST project. In the end, the competition came down to proposals from Northrop and Lockheed.

Skunk Works’ unusual faceted design ultimately won based heavily on the results of a so-called ‘pole off’ comparative test in which models of both designs were installed on a pole to measure their radar cross-sections (RCSs). Lockheed’s Advanced Projects Division had the additional benefit of a state-of-the-art computer program developed in-house by leveraging work done by a Russian mathematician, called Echo 1, which allowed for highly accurate radar cross-section (RCS) modeling on physical objects. Work at Northrop, which presented a design that may have been more aerodynamically sound but less stealthy, had also been hampered by convoluted internal relationships between teams working on different parts of the aircraft, all of which you can read more about here.

After Lockheed’s XST win, flight testing of its design, which became formally known as Have Blue and had also been nicknamed the “hopeless diamond” due to the basic shape from the Echo 1 computer program that gave birth to it, progressed steadily. The Air Force subsequently requested options for transforming it into an operational combat aircraft. In 1977, the team at Skunk Works put forward two core proposals.

The first of these was a fighter-sized type. The other was a larger ‘small tactical bomber’ more in line in terms of general role with the FB-111 Aardvark. These were referred to as the Advanced Tactical Aircraft-A and B, or ATA-A and ATA-B, respectively.

The ATA-B had an expected range of around 3,600 nautical miles and a payload of some 10,000 pounds, according to Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years of Lockheed, which Ben Rich wrote together with Leo Janos. Rich succeeded Kelly Johnson as director of Skunk Works in 1975 and remained in charge of the organization until 1991.

“We would come in relatively high – twenty thousand feet or more – giving us a tighter circle to aim at,” Rich says in Skunk Works of the proposed bomber design. “Also, because we would be invisible, our pilots would not have to duck and weave to avoid missiles or flak. We would have a clear shot to drop a pair of two-thousand-pounders.”

The Air Force picked the smaller, tactical-oriented ATA-A design to pursue, viewing it as a lower-risk option for turning Have Blue into an operational capability.

However, the Air Force had asked Skunk Works to develop those options in the wake of President Jimmy Carter’s decision to cancel work on the B-1A, a supersonic swing-wing bomber. The B-1A had been expected to engage its target by exploiting its high speed along with using low-altitude, terrain-masking flight routes and advanced electronic countermeasures.

The requirement for a new bomber never went away. In addition, Carter, as well as his Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, William (Bill) Perry, were major proponents of stealth technology, something they could not share with the American public at the time. For his very active support for the development of this technology within the Pentagon, Perry is widely credited as the godfather of stealth as we know it today.

The Air Force was also very receptive to the idea of a stealth bomber and, seeing the appeal of the technology to Carter, felt such a concept would be the best way to convince the President to support the development of a new bomber aircraft.

“Around the same time as [Deputy Chief of Staff of the Air Force for Research Development and Acquisition Lt. Gen. Thomas] Stafford solidified his strategy to get the Air Force a new bomber, Lockheed’s Ben Rich socialized the idea to develop a stealth bomber based on the Have Blue design with Bill Perry and Eugene Fubini, who was the Chairman of the Defense Science Board,” Air Force Lt. Col. Adam Young wrote in a doctoral dissertation completed earlier this year at the Naval Postgraduate School.

In 1978, what was dubbed the Advanced Strategic Penetrating Aircraft (ASPA) program began as a joint effort between the Department of Defense and the Air Force. Skunk Works’ initial bomber proposal is understood to have been more or less just a further enlarged version of the ATA-B design.

Unfortunately, the ATA-B derivative was known to have issues with “diminished low-observability” compared to the ATA-A-based Senior Trend aircraft, which would become known as the F-117A Nighthawk, and “poor aerodynamic performance,” according to Lt. Col. Young’s thesis. In fact, enlarging the ATA-B design actually appeared to make things worse. Data showed that the aircraft, initially developed under the nicknamed Have Peg, in an apparent nod to then-Strategic Air Command (SAC) boss Air Force Gen. Richard Ellis’ wife Peggy, was “so draggy it would need four aerial refuelings to reach its final target in the Soviet Union,” Stafford said in his book We Have Capture: Tom Stafford and the Space Race, which he wrote together with Michael Cassutt. Stafford quipped that with that kind of performance, the nickname should have been “Have Pig.”

It’s worth noting here that Gen. Ellis was a major proponent of ASPA and an opponent of the decision made by President Ronald Reagan’s administration to resurrect the B-1. Instead, he advocated for a “stretched” version of the FB-111 as an interim bomber before the introduction of a stealth design.

Northrop was eventually brought into the ASPA effort by Stafford directly as a result of the Air Force’s frustration with Lockheed’s progress on Have Peg, or lack thereof, according to Lt. Col. Young’s thesis. It’s not entirely clear what was happening on Skunk Works’ end, but, from Young’s dissertation, it would appear that its bomber project was negatively impacted by a combination of overconfidence, miscommunication with the Air Force and the Pentagon, and other priorities. The primary focus at Skunk Works at that time appeared to be on the development of the tactical-oriented Senior Trend.

Ben Rich, among others at Lockheed, clearly felt that the existing Senior Trend contract coupled with the progress shown there would give the company a substantial leg up with regard to ASPA and the follow-on Advanced Technology Bomber (ATB) program that eventually subsumed it. In addition, Skunk Works had already built and flown an airworthy stealth design, Have Blue, and was confident that it could deliver a stealth bomber derived from the same design concepts that would ‘only’ cost $200 million apiece.

“Right now, we’ve got a contract and also the inside track on the next step, which is where the big payoff awaits: building them their stealth bomber. That’s why this risk is worth taking,” Ben Rich wrote in his memoir. “They’ll want at least one hundred bombers, and we’ll be looking at tens of billions in business. So what’s this risk compared to what we can gain later on? Peanuts.”

“While [Under Secretary of Defense] Perry could not give Rich a guarantee that Lockheed would win the contract, Perry and [the Defense Science Board’s] Fubini were a highly receptive audience, which left Rich convinced Lockheed was a shoo-in for the stealth bomber contract,” Lt. Col. Young says in his thesis. “After all, as far as Rich knew, Lockheed was the only stealth aircraft designer in the game.”

In something of an ironic twist given Skunk Works’ own experience with XST, as it turned out, it was very much not the only entity making significant progress in stealth developments at that time. Northrop had separately won a contract to develop a stealthy aircraft as part of DARPA’s Battlefield Surveillance Aircraft Experimental program, or BSAX. The resulting design, officially nicknamed Tacit Blue, but often referred to as the “Whale” and the “alien school bus,” looked positively bizarre, but demonstrated advanced stealth capabilities. BSAX, just like the A-12 and SR-71 had been, was shrouded in such secrecy that Lockheed was not aware of its existence at the time, let alone the performance of the demonstrator.

“Shortly after he decided to unilaterally bring Northrop into the stealth bomber competition, Stafford arranged a meeting with Northrop’s CEO, Tom Jones [Thomas V. Jones; not to be confused with Thomas H. Jones, Northrop Grumman’s current Corporate Vice President and President of the company’s Aeronautics Systems division] at a conference in June of 1979,” according to Lt. Young’s doctoral thesis. “Stafford told Jones what he was after and sketched out the desired capabilities (i.e., radar cross section, range, payload, etc.) on the back of an envelope.”

“A week after Stafford met with Northrop’s Jones, Stafford provided the identical bomber specifications to Lockheed, in full knowledge that the ‘specifications exceeded the performance outlined in their Have Peg design,'” the dissertation continues. “Despite Stafford’s hope that the expanded requirements would result in a better design, Lockheed’s follow-up briefing to Stafford in July 1979 was again unimpressive. According to Stafford, it ‘still had too much drag for a long-range bomber.'”

Exactly how Skunk Works’ design evolved from the original Have Peg concept to the final iteration of the design, which was eventually given the formal nickname Senior Peg, is unclear. There is at least one available artist’s conception that shows a configuration much closer, visually, to the F-117A compared to a known picture of an RCS model of Senior Peg. The RCS model certainly fits the description of the final Lockheed proposal from a 1989 article in The Washington Post, which called it an aircraft that “dimly resembled a larger, flattened F-117.”

Ben Rich, in his memoir, says that when the Defense Science Board’s Fubini saw a model of Senior Peg he found the general shape so similar to Northrop’s concept that he suggested Lockheed had somehow managed to get its hands on one of its competitor’s models. Rich says that he was completely unaware that Northrop’s bomber was any sort of flying wing or blended wing body design until that point.

Regardless, by all indications, Lockheed was absolutely stunned by its loss in 1981. Northrop’s final design turned out to be an advanced, next-generation flying-wing type aircraft made viable by developments in fly-by-wire technology. It also leveraged the work being done for Tacit Blue under the BSAX program and lessons learned from the company’s loss in the XST competition.

Just months before the final decision was made, another “pole off” was held to check both entrants’ radar cross-sections. This reportedly showed that Northrop’s proposal, which had been developed under the official nickname Senior Ice, was stealthier than Senior Peg – something Skunk Works’ Ben Rich disputed at the time and thereafter – in addition to being more aerodynamically efficient and promising the ability to carry larger payloads out to greater ranges.

“The big difference between them was that John Cashen [Northrop’s chief engineer for Senior Ice] was getting advice from a three-star general at the Pentagon to make the airplane as large as possible to extend its range, while I was listening to a three-star general at SAC headquarters in Omaha, who urged me to stay as small as I could get away with while still meeting the basic Air Force requirements for the new bomber,” Lockheed’s Ben Rich wrote in Skunk Works. “‘I’m telling you, Ben, that small will win over big, because budget constraints will force us to go with the cheaper model in order to buy in quantity.’ His strategy made sense.”

“But it also created a few significant structural differences in the two models,” according to Rich. “Because our airplane was designed to be smaller, the control surfaces on the wing were smaller, too, which meant we needed a small tail for added aerodynamic stability. Northrop had larger control surfaces and needed no tail at all. So they had a slight advantage in lift-over-drag ratios, which meant a better fuel efficiency for extended-range flying.”

In his book, Rich asserts that he was told later that Northrop’s offer “had better payload and more range and therefore would be the better buy” since “it would need to make fewer sorties because it carried more bombs than our model,” which “evened out our advantage in being less visible.”

In his thesis, Lt. Col. Young says that Kevin Rumble, who had been part of the contracting team that made the final determination, told him that he believed there was another major factor that swung against Lockheed in the end. This was the insertion of an additional requirement for the ATB to have a low-altitude penetrating capability, something that would fundamentally change the design of the B-2, as you can learn more about here.

Without that change, “Rumble, recalled that, ‘Lockheed would have very likely been the winner’ – they were the less risky option, were cheaper, and ‘could probably pull off a fast IOC initial operational capability,'” according to Young.

With that in mind, it is clear the Air Force had decided in the end that affordability was not a significant enough factor to choose Senior Peg, which stood to be significantly cheaper than its competitor. In his thesis, Lt. Col. Young says Rumble also told him that “Senior Ice was estimated to cost $9.4 billion versus $7.8 billion for Lockheed’s Senior Peg for Full Scale Development.”

Fast forward and the B-2 Spirit would become the most expensive aircraft ever bought. This was due to a myriad of factors, including ballooning development costs, changes made by the Air Force for requirements, and the crumbling of the Soviet Union that led to massive decreases in defense spending. The latter reality prompted consecutive cuts in B-2 production, often referred to as the budgetary ‘death spiral’ in Pentagon parlance. Still, really, the B-2 was incredibly groundbreaking and with just 21 ever built, has always been somewhat experimental in nature.

There is an interesting parallel here with the B-21 today, which, like Senior Peg, was designed from the outset to trade size and some complexity for lower cost and faster acquisition. We will never know what would have come of the ATB program if Senior Peg had won, but one has to wonder if Lockheed’s approach would have resulted in a larger, more robust stealth bomber force and what exactly would have been traded in capabilities for it.

Regardless, in the end, the Air Force got great value out of the small fleet of B-2s they ended up acquiring and that aircraft has given birth to the highly promising B-21 Raider. But at least now we can see our best approximation of what the Skunk Works’ competing ATB design would have looked like if it was chosen to usher in the strategic stealth bomber revolution.

Contact the authors: tyler@thedrive.com and joe@thedrive.com