A senior U.S. Space Force officer has stressed that China’s new hypersonic weapon system is indeed orbital in nature and could be able to stay in space for an extended period of time. This is the latest piece of official information about this novel system that reportedly uses some kind of hypersonic glider, which may be capable of launching its own projectiles to actually execute a strike.

Space Force Lieutenant General Chance Saltzman, the Deputy Chief of Space Operations for Operations, Cyber, and Nuclear, responded to questions about this new Chinese strategic weapon during an online event hosted by the Air Force Association’s Mitchell Institute earlier today. Saltzman, who transitioned from the Air Force to the Space Force last year, “has overall responsibility for Operations, Intelligence, Sustainment, Cyber, and Nuclear Operations of the United States Space Force,” according to the service’s website.

“I think the words that we use are important, so that we understand exactly what we’re talking about here,” Saltzman explained. “I hear things like hypersonic missile, and I hear suborbital sometimes.”

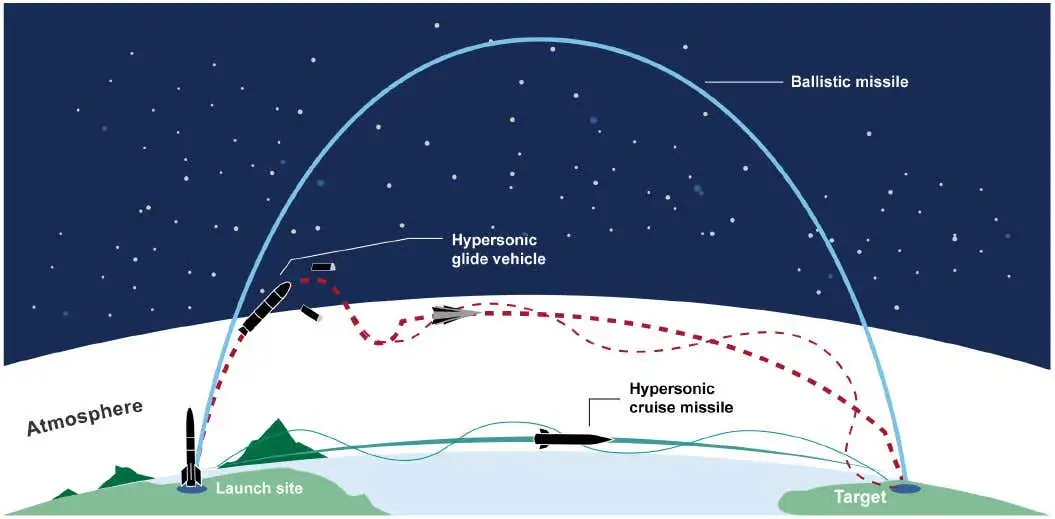

Hypersonic speed is typically defined as anything above Mach 5. Suborbital refers to objects that may technically reach space, such as more traditional intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM), but that do not enter any sort of orbit around the planet.

“This is a categorically different system, because a fractional orbit is different than suborbital,” Saltzman continued. “A fractional orbit means it can stay on orbit as long as the user determines and then it de-orbits it as a part of the flight path.”

Historically, a fractional orbit has been defined as one in which the vehicle in question reaches orbit, but is brought back to Earth before fully circling the planet. However, the common working definition of so-called Fractional Orbital Bombardment Systems (FOBS), of which China’s system would seem to be a particularly novel example, has often been expanded to include concepts that do complete one or more revolutions. Saltzman is clearly suggesting here that the Chinese system is designed to spend a more protracted period in space.

That description is broadly in line with comments from now-retired Air Force General John Hyten, whose last post was as Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, earlier this month. “It went around the world, dropped off a hypersonic glide vehicle that glided all the way back to China, that impacted a target in China,” he had said during an interview with CBS News.

Then, on Nov. 21, the Financial Times newspaper, which broke the original news about this orbital system back in October, published a new story saying that during one of two tests earlier this year, the glider released its own projectile. It remains unclear what the object was and why it was released, as The War Zone

has previously explored in-depth.

The basic idea of a FOBS dates back to the 1960s and the Soviet Union, though other countries, including the United States and China, have explored similar concepts in the intervening decades. The system that the Soviets are known to have developed and deployed to a limited extent during the Cold War involved an ICBM-like missile that would put a more traditional re-entry vehicle containing a nuclear warhead into orbit. That warhead could then be de-orbited in a controlled manner to strike a target.

This kind of FOBS offers a number of advantages over a more typical IBCM, such as a depressed flight profile and a capability to hold any target within a strip of geography along the orbit at risk, presenting challenges to an opponent’s early warning networks and their ability to anticipate where and when a strike might occur. Beyond that, the orbital profile means such a weapon could attack from the opposite direction from which the bulk of an enemy’s existing early warning infrastructure might be pointed.

From everything that we know so far about China’s system, it uses some kind of hypersonic glider capable of high-speed, largely level, atmospheric flight and that has at some degree of maneuverability, rather than a typical re-entry vehicle. This, at least in principle, would blend the defense-evading benefits of a FOBS with those of a hypersonic boost-glide vehicle. Financial Times‘ report that the vehicle in this new Chinese system may be able to release projectiles itself, a technically complex capability for anything moving a hypersonic speed, would only present more challenges for a defender.

At the same time, if this Chinese weapon system is meant to stay in some kind of sustained orbit, even one that is rapidly degrading, that takes it fully around the Earth more than once, it would no longer really be “fractional orbital” in nature. The Soviets had specifically asserted that their FOBS was not designed to complete a full revolution around Earth specifically to get around the provisions of the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, to which China is a party and that prohibits the permanent stationing of nuclear weapons in orbit.

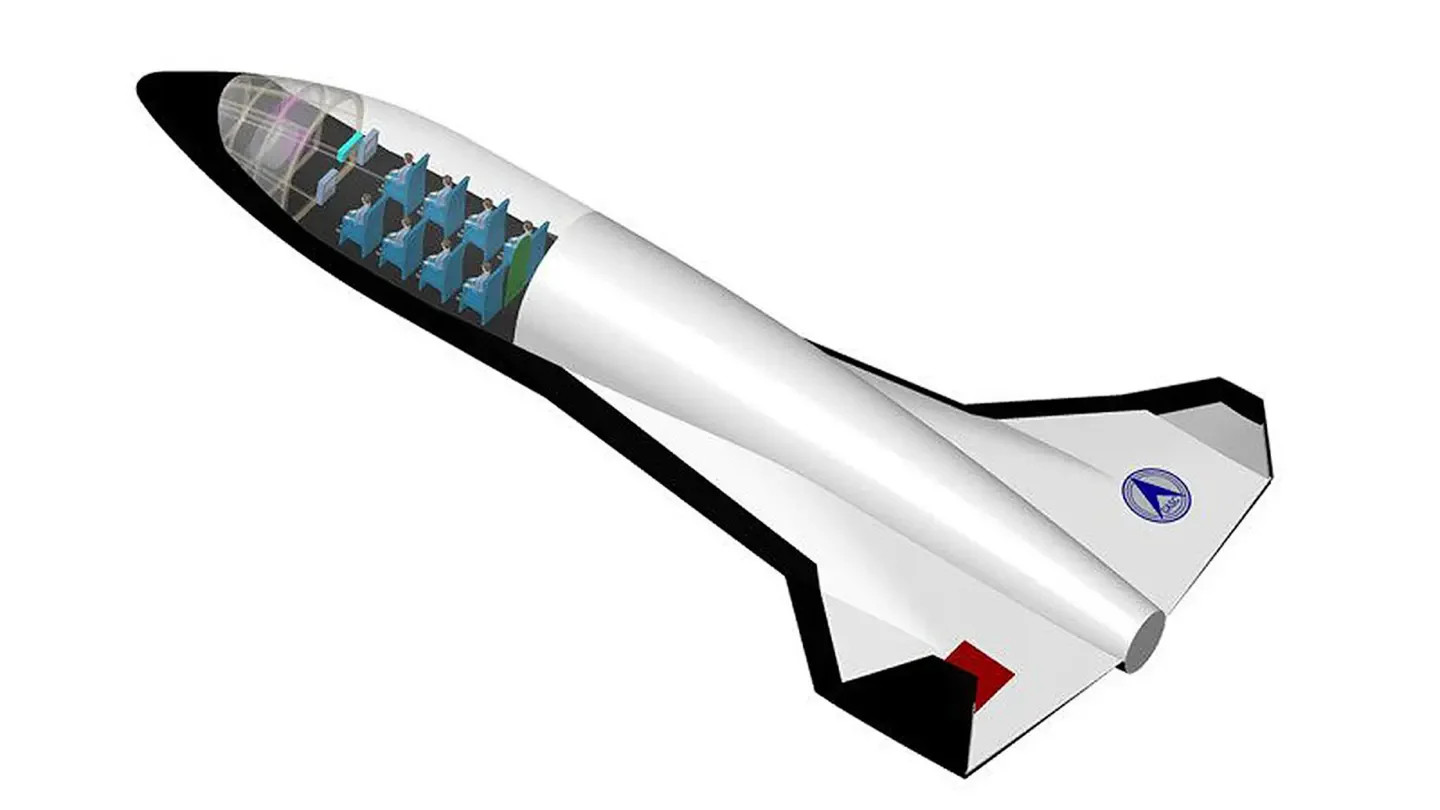

Beyond that, questions remain about the exact design and capabilities of the hypersonic glide vehicle. Its apparent ability to carry and release payloads has caused renewed speculation that it could be related in some way to a reusable spaceplane. Though The War Zone, among others, debunked an initial claim from the Chinese government that a test of its new orbital weapon system had been confused with one involving a spaceplane, the country is known to be working on a number of different such designs for both military and civilian purposes. Of course, this novel orbital weapon might use a more warhead-like glider that can release multiple independent munitions, or other payloads, such as countermeasures, during its flight. We still really can’t say with any certainty and Saltzman’s remarks do not preclude any particular design.

Separately, Lieutenant General Saltzman raised interesting points about how the difficulties in detecting and tracking the flight of such a weapon could also make it hard to quickly attribute it to a particular country. This could, in turn, reduce the amount of time a defender has to spot and then categorize an incoming nuclear strike and then decide how to respond.

“A lot of our warning, you know, is based on ballistic missiles because that’s the been the primary threat for so many years,” Saltzman said. “And so it’s incumbent on the Space Force, in my mind, to make sure that we’re developing the capabilities to track these kinds of weapons. Before they’re launched, ideally, but then throughout their lifecycle – either on orbit or in execution of their mission set.”

“If we can track we can attribute … I think we can deter,” he added. “[Space Force needs] to make sure that we’re developing those capacities to be able to track and hold accountable nations who are using these kinds of destabilizing weapons.”

This is hardly the first time that senior U.S. officials have warned about the potential impacts of not being able to quickly detect and track incoming hypersonic weapons. Saltzman’s remarks on these issues do give additional weight to comments from General Hyten during his CBS News interview in which he warned that this new Chinese development offered an inherent surprise first-strike capability. Whether or not China would actually posture itself to do be able to do this, the deployment of this orbital weapon could have serious negative ramifications if the U.S. government, among others, feels a need to actively prepare for this potentiality.

All told, while many key details about this new Chinese weapon system remain murky, the U.S. government’s assessment is clearly that it has a true orbital component and that this is a key contributing factor in its potential to upset the strategic balance of power between the two countries.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com