U.S. Navy Vice Adm. Jon Hill, the head of the U.S. Missile Defense Agency, or MDA, says that the multi-purpose SM-6 missile is the only weapon in the country’s arsenal at present that offers any ability to knock down highly-maneuverable hypersonic threats. This comes after the agency disclosed plans last year to test an unspecified version of the SM-6 against an “advanced maneuvering threat,” a term typically associated with unpowered hypersonic boost-glide vehicles, sometime in the 2024 Fiscal Year.

Hill made his remarks about the SM-6 during a discussion about hypersonic defense capabilities at the American Society of Naval Engineers’ Combat Systems Symposium, which opened on Jan. 31 and ends today. MDA is leading an effort to develop a layered defense architecture against hypersonic threats that includes an array of terrestrial and space-based sensors and multiple types of interceptors, as you can read more about here.

The SM-6 series “is really the nation’s only hypersonic defense capability,” Hill said, without specifying any particular version of this missile. He added that these weapons have a “nascent capability” to engage incoming hypersonic threats that are maneuvering to a high degree.

“We didn’t call it that back when we got the letter from the CNO [Chief of Naval Operations, the Navy’s top uniformed officer] to go develop this program,” he explained. “But the whole idea was to handle high-speed maneuver.”

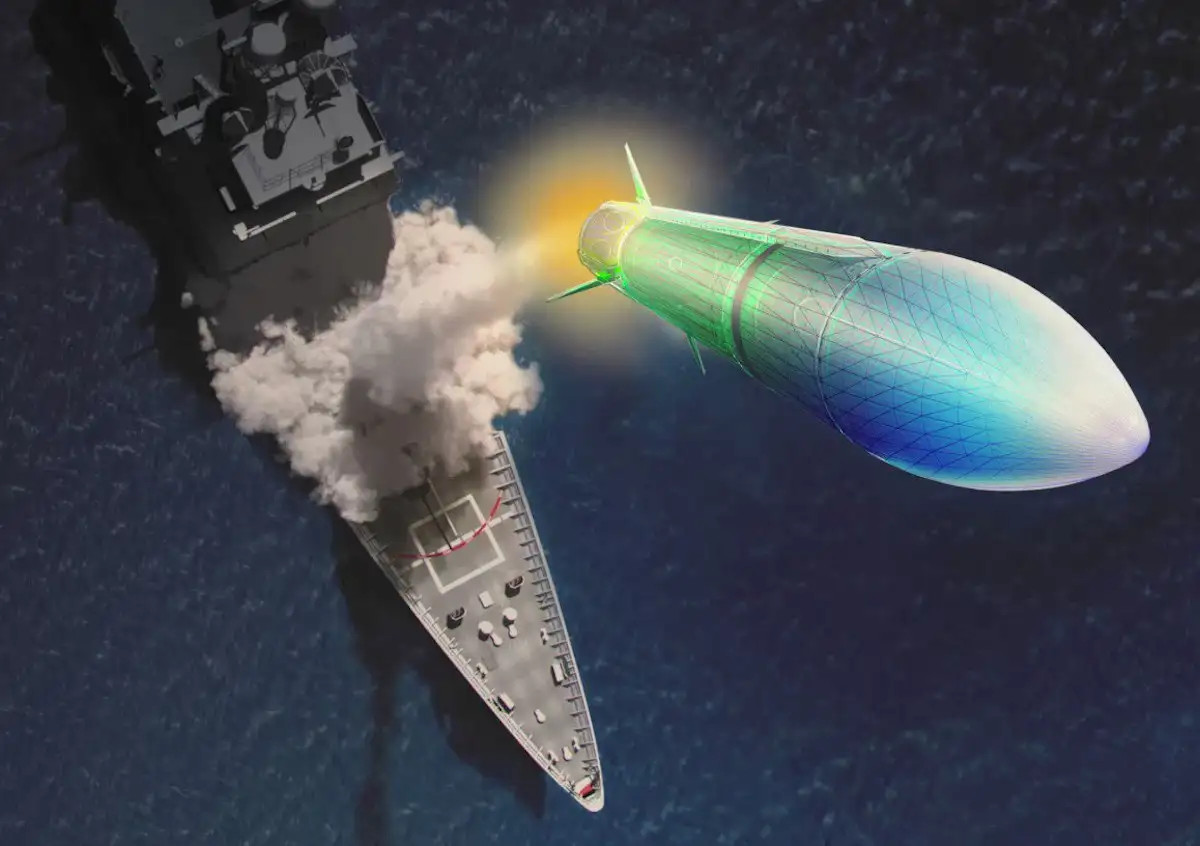

Hill’s comments are immediately interesting for a number of reasons. Currently, there are two variants of the SM-6 in service, the Block I and Block IA, while a third version, the Block IB, is under development. The Block IB missile is substantially different from the two earlier types, including its completely redesigned body and a larger rocket motor. It is expected to be able to reach hypersonic speed itself and therefore have greater capabilities against hypersonic threats.

The Block I and Block IA missiles are generally described as surface-to-air missiles, though they also have a surface-to-surface strike capability. In addition, they do have missile defense capabilities, but which are more typically described as the ability to engage incoming cruise missiles, as well as more traditional ballistic missiles or separate re-entry vehicles they release in the terminal phase of flight.

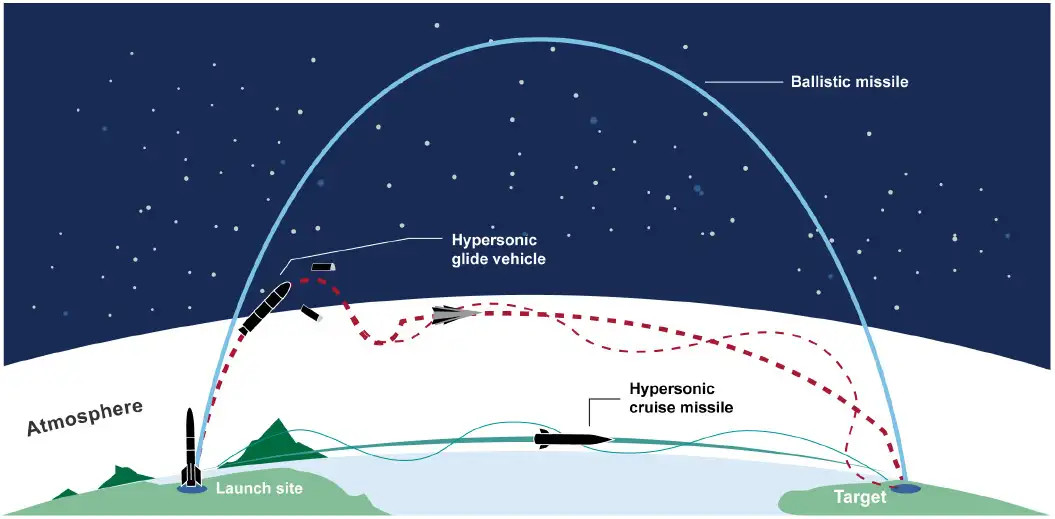

It is important to note that those targets are traveling at hypersonic speeds at that point, but that even advanced maneuvering types would not be as nimble as a purpose-built hypersonic boost-glide vehicle. In addition, boost-glide vehicles travel along an atmospheric trajectory compared to more conventional ballistic threats, which also makes them more difficult to spot and track.

What Hill appears to have disclosed now is that the Block I and IA missiles already have at least some degree of capability against these more maneuverable hypersonic threats, or were at least designed with that capability in mind from the outset. It is possible that only some SM-6s currently in service have this particular ability, as well, which might be the product of post-delivery modifications. Beyond that, the envelope in which an existing SM-6 is able to engage hypersonic threats could easily still be very small and the missile might only be effective at all against certain specific types of targets.

The U.S. Navy fired a pair of what have been referred to as SM-6 Dual IIs, a ballistic missile defense-optimized subvariant of either the Block I or Block IA, during an MDA-led test last year. Those interceptors failed to knock down a surrogate for a traditional medium-range ballistic missile.

All told, whatever capability existing SM-6s might have against hypersonic threats would still appear to be limited. MDA is actively pursuing a new interceptor optimized against things like boost-glide vehicles as part of the Glide Phase Interceptor (GPI) program. In November 2021, Raytheon, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman received contracts to build competing GPI designs. Raytheon is the prime contractor behind the SM-6 series.

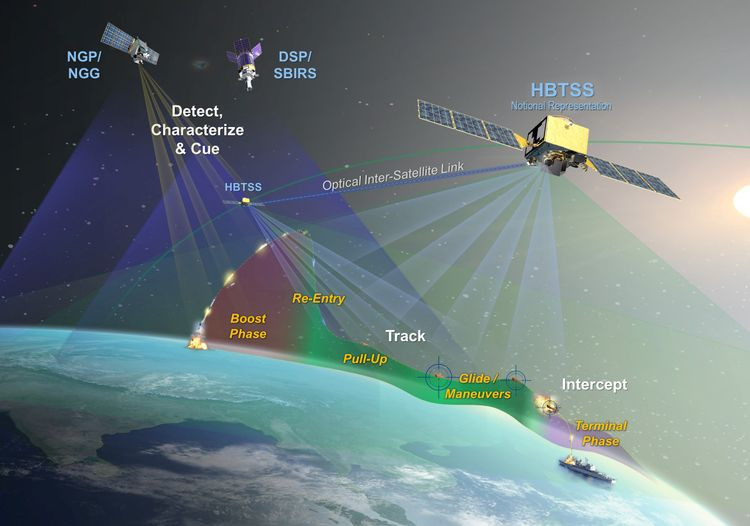

Interceptors of any kind are, of course, just one part of the hypersonic defense equation. Sensors able to detect and provide target-grade tracks of those threats are essential. The U.S. military has already identified gaps in its capabilities in this regard and is working to fill them, including through the development of a space-based Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor (HBTSS). MDA has hired both Northrop Grumman and L3Harris to build prototype HBTSS satellites with the goal of starting on-orbit testing of the two designs in 2023. What the final HBTSS constellation might look like and how many satellites it might have, in total, remains unclear.

“We’re going to take those first hypersonic tracking space-based sensors in coordination with the U.S. Space Force and we’re going to get them on in orbit,” Vice Adm. Hill said in regards to HBTSS at the Combat Systems Symposium. “That’s through a competitive process and we’re really excited about that. We did so much risk-reduction on the ground we’re absolutely confident that those sensors are going to deliver what we need when we put them up.”

“We’re going to leverage space cueing and fire control from space because, to handle maneuvers across the globe, you’ve got to look down” Hill explained, emphasizing the importance of added sensor capabilities in space. The “field of view is limited from [terrestrial] radars and we’re running out of islands to put radars on.”

Terrestrial sensors are “not always in the exact right place, because many of them are land-based and stationary,” he added.

HBTSS is only one of a number of space-based sensor programs underway within the U.S. military that could support missile defense missions. This includes an effort that the Space Development Agency (SDA) is leading that is exploring the possibility of deploying a distributed space-based sensor and data-sharing network using smaller satellites.

MDA has already outlined how new and old satellites could be used to expand the capabilities surface-based interceptors, either launched from ships or land-based sites, against hypersonic threats. With cueing from those systems, a launch platform would be able to conduct so-called engage-on-remote and launch-on-remote type intercepts that do not rely entirely, or at all, on its own organic sensors. You can read more about these concepts here.

Expanding hypersonic defense capabilities has become an important area of focus for the U.S. military as these threats become more pronounced and continue to proliferate. Russia and China have both fielded missiles tipped with hypersonic boost-glide vehicles, as well as more traditional ballistic missiles with advanced maneuvering capabilities, and continue to develop other related capabilities. Last year, it emerged that the Chinese have been testing a particularly novel fractional orbital bombard system that utilizes a hypersonic vehicle of some kind.

In addition, in the past year or so, North Korea has demonstrated that it is at least attempting to develop its own hypersonic boost-glide vehicle capability, as well as ballistic missiles carrying more conventional re-entry vehicles with improved maneuverability. Iran appears to be trying to follow suit, at least in regards to the development of more advanced maneuverable re-entry vehicles, as well.

Vice Adm. Hill did stress that existing sensor capabilities can still provide some degree of detection and tracking against hypersonic threats. “We’re seeing them, we’re capturing data, we’re collecting on them,” he said. “We’re not at zero.”

According to Hill, at least for the moment, SM-6 missiles offer the only option, however limited, to then try to destroy those threats.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com