Japan is reportedly pursuing development of two hypersonic weapons using different boost-glide vehicle warheads. The plan could offer the Japanese military game-changing capabilities to deter its regional opponents, primarily China in the East China Sea, and is also the latest signal that the country is moving away from its pacifist post-World War II constitution.

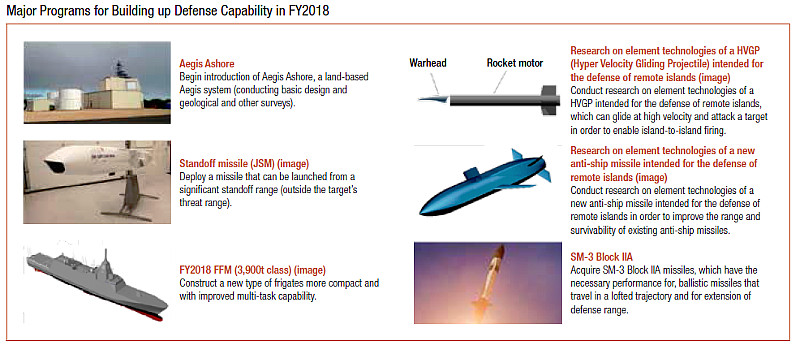

On Oct. 15, 2018, Japan’s Mainichi Shimbun newspaper, citing unnamed sources, said the country’s Ministry of Defense had crafted the hypersonic weapon plan with an eye toward having the initial system in service no later than 2026. The second type would hopefully arrive in 2028. The Japanese government first officially revealed it was working on what it calls the Hyper-Velocity Gliding Projectile (HVGP), in an annual defense white paper that came out in August 2018.

Hypersonic speed is defined as anything above Mach 5. Boost-glide vehicles, one of the most common hypersonic weapon designs, are unpowered and require some sort of booster to get them to the appropriate speed and altitude, after which they glide back down to earth. Ballistic missiles, or derivatives thereof, have traditionally served as the launch platform for these systems.

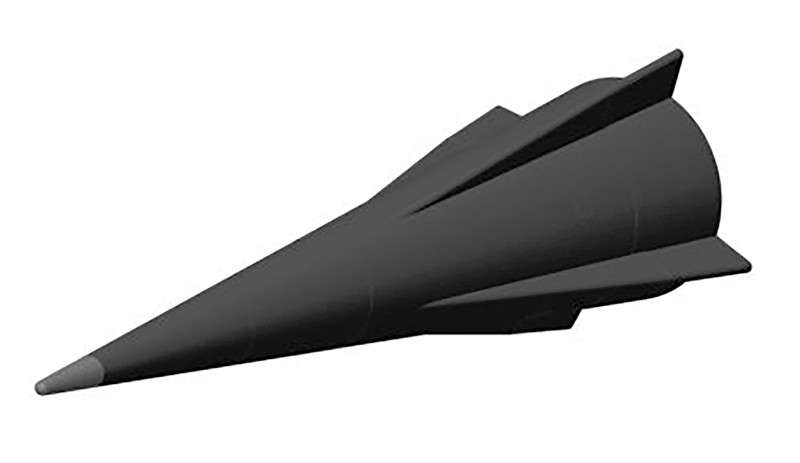

The initial Japanese design will by a conical boost-glide vehicle with small fins to adjust course, according to the Mainichi Shimbun. The follow-on hypersonic weapon will use a flatter “talon-shaped” warhead. The Ministry of Defense budgeted more than $40 million in the 2018 Fiscal Year for hypersonic weapon development and has requested more than $120 million to continue that work in the upcoming 2019 fiscal cycle.

This two-tier approach makes good sense and is almost identical to the plan the U.S. military has put in place for its own hypersonic boost-glide vehicle development strategy. Still, there is no indication that the Japanese and American efforts are tied together in any way.

The basic concept of the conical design is well understood at this point and has been the subject of tests and experiments since the 1980s. This makes it a relatively low-risk option that could help reduce the overall time to develop, test, and field the complete weapon.

This type of boost-glide vehicle, however, generally has a limited overall glide time, which can lead to a reduced range. The HVGP program is seeking weapons that can strike targets between around 185 and 310 miles away, but it’s unclear if the two ranges reflect the potential differences in capabilities between the two types of hypersonic warheads.

The conical design is also typically less maneuverable and less accurate than more advanced shapes also in development around the world. These are major issues for hypersonic weapons, the benefits of which are more pronounced if they are more agile and precise, as we at The War Zone have explored in detail in the past.

The ability of hypersonic weapons to rapidly change course and follow unpredictable flight paths makes it difficult for opponents to detect and defend against them. As a result, they offer the capability to engage time-sensitive and other critical targets at long ranges with little to no notice.

So, getting even a less than ideal system into service in the near-term would allow the Japanese to begin realizing the benefits of having operational hypersonic weapons and could help support the development of the follow-on system. For instance, it’s very likely that any improved boost-glide vehicle would use the same booster or a version thereof.

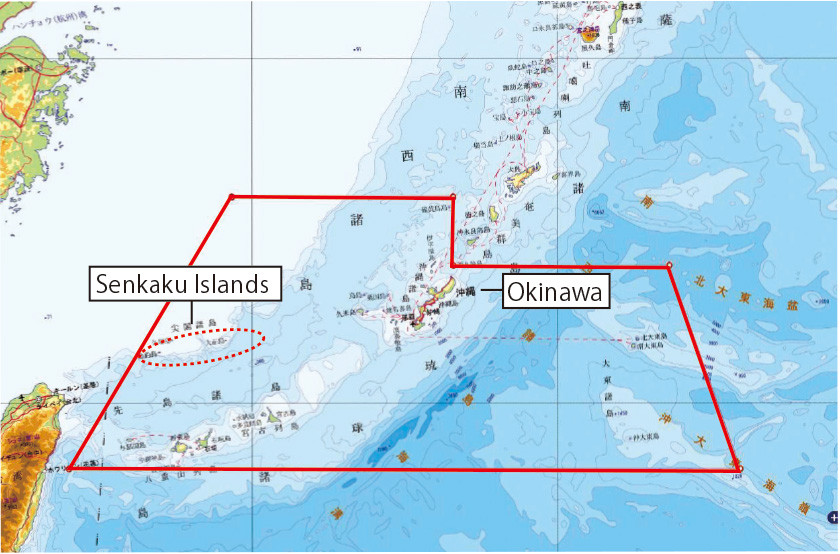

The HVGP program’s primary stated objective is the development of a weapon “for the defense of remote islands, which can glide at high velocity and attack a target in order to enable island-to-island firing,” according to the Ministry of Defense’s white paper. “Remote islands” here is a reference to a hotly disputed group of islands that the Japanese refer to as Senkaku and the Chinese refer to as Diaoyu.

The Senkakus lie more than 260 miles southwest of Okinawa, which itself is more than 300 miles away from the Japanese Home Islands. The area is much closer to the Chinese mainland and Chinese warships and military aircraft routinely conduct patrols in the area to challenge Japan’s claims.

Hypersonic weapons situated in Okinawa, or on other Japanese-owned islands closer to the Senkakus, could offer Tokyo a new means of deterring China. The boost-glide vehicles would present a highly responsive and flexible threat to Chinese forces during any actual conflict, especially depending on what assets the Japanese might’ve been able to move into the area before the outbreak of hostilities. This could force Beijing to rethink taking any more concrete action to assert its own territorial claims in the region.

A weapon system with a maximum range of 310 miles wouldn’t be able to reach other regional threats, such as North Korea, from the Japanese Home Islands, but it might be possible for Japan to adapt any hypersonic weapon it develops into a sea-launched version that could put those targets within striking distance. A larger booster could also increase the overall range of the system.

This could help reduce Japan’s reliance on allies to conduct the actual strikes in the event of a conflict on the Korean Peninsula or the appearance of an imminent threat to Japanese interests elsewhere in the region. Japan has often been right in the path of North Korean ballistic missile tests and has largely lacked any credible means to strike at those weapons before launch or retaliate afterward on its own. The Japanese Ministry of Defense is also developing stand-off, air-launched, land-attack cruise missiles that would give it more capability in this regard.

But hypersonic weapons that can strike well beyond Japan’s territorial boundaries would also be as clear an indication as any of a shift away from the purely “defensive” nature of its military, as enshrined in Article Nine of the country’s constitution. Since Japan does not presently have ballistic missiles to use as boosters for hypersonic vehicles, the HGVP program could also to the development of those systems, which could have an “offensive” character, as well. In 2016, there were unconfirmed reports that the Japanese were working on a ballistic missile development program to defend the Senkakus, which could be related to the hypersonic project.

In May 2017, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said he wanted to complete an exhaustive review the law by 2020 in order to ensure that it still reflected the geopolitical state of East Asia and Japan’s place in the world as a whole. The push has raised the ire of China and both North and South Korea, all of which suffered greatly under Japanese occupation during World War II and are all steadfastly opposed to any attempts by the country to re-militarize for operations outside its borders.

Still, Abe and his government may find support for both transforming Article Nine and the development of advanced weapon systems such as a hypersonic boost-glide vehicle from the United States and President Donald Trump in particular. Trump and Abe have forged a close public bond, especially over Japan’s plans to purchase American-made arms. “To deal with the difficult security situations, it is important for us to continue to introduce sophisticated equipment, including American equipment, so that Japan’s defense capability can be strengthened,” Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga explained to reporters, paraphrasing what he said Abe had told Trump, during a press conference on Sept. 26, 2018.

No matter how the HGVP program proceeds and what other weapon developments efforts it might feed into in the future, it seems clear that Japan is determined to develop its own hypersonic weapon capability and could have a working weapon within the next 8 years.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com