The Chinese government has denied a recent report that the country tested a strategic weapon system that involves launching a nuclear-capable hypersonic glide vehicle into orbit before it re-enters the atmosphere to make its final flight toward its target. The country’s foreign ministry claimed that the test in question was of a reusable spaceplane, not a weapon. However, that official statement referred to a spaceplane launch in July, while the original report from the Financial Times newspaper said that the orbital bombardment system was tested in August, as you can read more about here.

Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian first issued this denial at a press conference on Oct. 18, 2021. He gave his remarks in response to questions from reporters for Bloomberg and AFP.

“As we understand, this was a routine test of [a] space vehicle to verify technology of spacecraft’s reusability,” Zhao said, according to an official transcript. “After separating from the space vehicle before its return, the supporting devices will burn up when it’s falling in the atmosphere and the debris will fall into the high seas.”

“As I just said, it’s not [a] missile, but a space vehicle,” Zhao continued when asked specifically if the spacecraft he was referring to was the vehicle described in the Financial Times article.

Bloomberg‘s James Mayger and the BBC‘s Stephen McDonell both subsequently reported that the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs had further confirmed to them that Zhao was talking about a spaceplane test in July. As already noted, the orbital bombardment system test reportedly took place in August.

China’s state-run China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, or CASC, did publicly announce what it said was a successful reusable spaceplane test in July, but it described that flight as sub-orbital. CASC did not say how this spaceplane had taken flight but did say that the test had been carried out from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in China’s Inner Mongolia region. In 2020, there had been another test from Jiuquan that saw a Long March 2F carrier rocket boost what was only referred to as a “reusable experimental spacecraft.”

The Financial Times reported that a Long March 2C carrier rocket had been used in the orbital bombardment test and that this launch, the 77th involving this variant of the Long March family, had not been publicly disclosed. The 76th Long March launch took place on July 19, while the 78th occurred on Aug. 24, according to that newspaper.

The CASC spaceplane test that Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao was apparently referring to took place on July 16. Furthermore, the Financial Times‘ sources said that the weapon completed a full profile flight including an impact that reportedly missed the intended target area by dozens of miles. CASC said the spaceplane successfully landed at an airport after its flight. It also does not seem likely that the U.S. Intelligence Community would have confused these two events if they had each occurred as reported.

Regardless, experts and observers have now raised questions about where there may be some degree of overlap in Chinese reusable spaceplane projects and this reported orbital bombardment system. This would hardly be the first instance of an ostensibly civilian or commercial aerospace project in China having links to the country’s military and potentially being a dual-use research and development effort. At the same time, China has openly fielded and continues to develop actual hypersonic glide vehicle weapons.

“Is this China’s response to the US insisting the X-37B is in no way a weapon?” Brian Weeden, the Director of Program Planning at the Secure World Foundation, wrote on Twitter, as being among a number of significant questions that remain unanswered about this reported Chinese test. There are long-standing but totally unsubstantiated rumors that the X-37B miniature space shuttle, which the U.S. Space Force now operates, could have some sort of orbital bombardment role.

“Is every spaceplane now a FOBS?” Weeden added, referring to a Fractional Orbital Bombardment System.

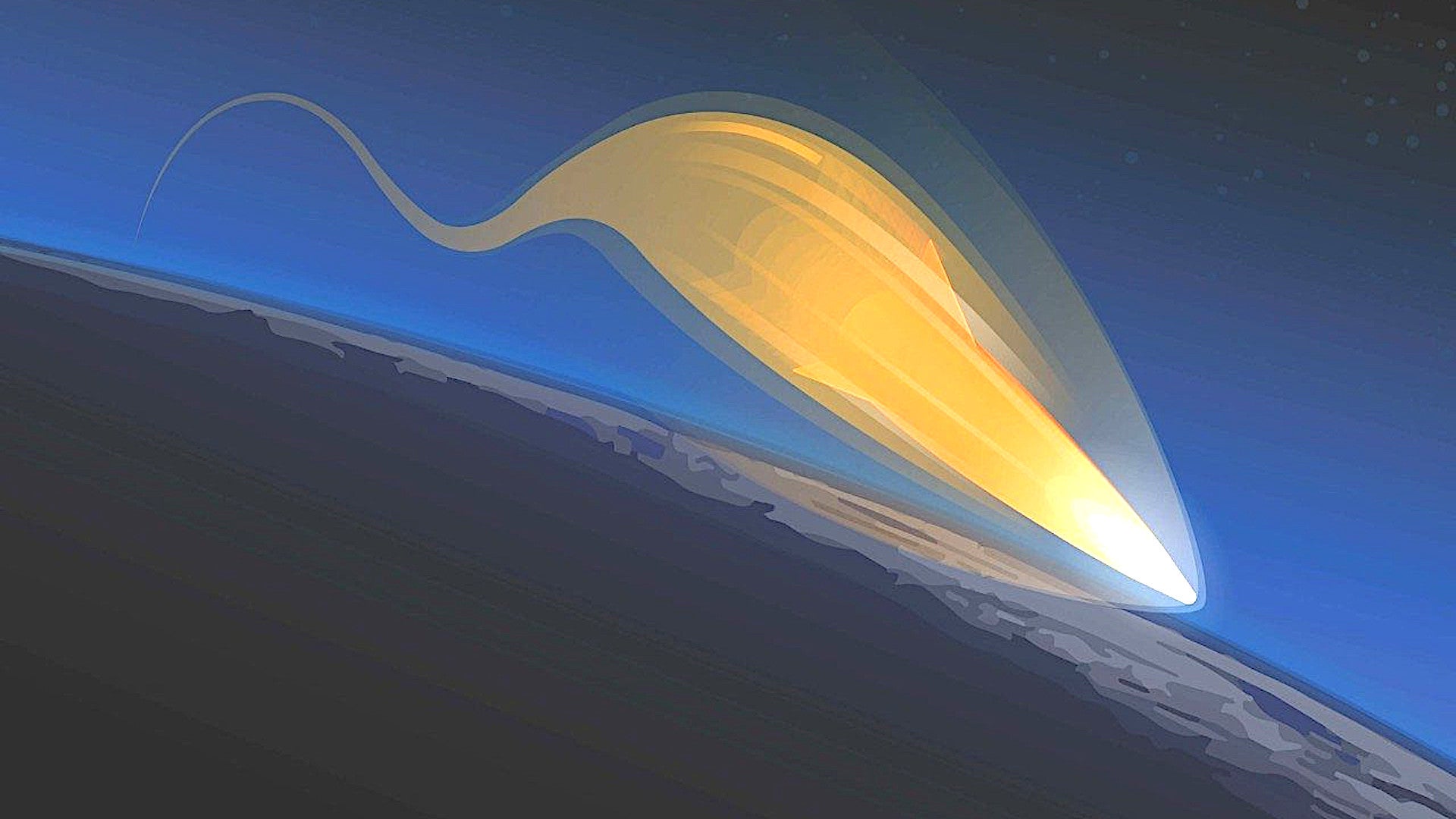

Of course, the basic concept of a FOBS dates back to the Soviet Union in the 1960s. In principle, compared to a more traditional intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), the semi-orbital nature of a FOBS system effectively eliminates any range limitations and makes it difficult, if not impossible for an opponent to determine what the intended target or targets might be. In addition, the FOBS’ lower trajectory of flight makes it more difficult for high-angle, ground-based early-warning radars to detect it in the first place, presenting additional challenges for the enemy.

Using a hypersonic glider of some kind as the warhead-carrying portion of a FOBS adds a new dimension of unpredictability to the weapon. The glider would provide a highly maneuverable platform to bring the warhead to the target, giving it much more significant capabilities to either dodge enemy air and missile defenses or simply strike from an unexpected vector where there are no defenses. A strike by way of the South Pole would, for example, come from the exact opposite direction from where much of the U.S. missile defense shield is pointed. Any attempt to intercept a hypersonic glide vehicle, in general — even under the most optimal conditions — is something the U.S. government and others have publicly acknowledged is an extremely difficult proposition.

So, whether or not this reported Chinese FOBS program is related to any spaceplane projects or not, the immense defense-busting capability that a FOBS system utilizing a hypersonic glide vehicle has the potential to offer, combined with the U.S. government’s efforts to improve and expand its ballistic missile defenses, would seem to be the most immediate reason for the Chinese to even explore this weapon. It is also worth noting that the regime in Beijing did have a FOBS in development in the 1960s and 1970s, known as the Dongfeng-6 (DF-6), but this project was ultimately canceled, reportedly due to technical issues. The Chinese aerospace and missile industries are significantly more capable of pursuing these kinds of high-technology efforts now than they were 50 years ago.

Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall said as much when he publicly asserted, seemingly out of nowhere, that the Chinese military was working on a FOBS-like weapon at the Air Force Association’s annual Air, Space & Cyber Conference in September. “If you use that kind of an approach, you don’t have to use a traditional ICBM trajectory. It’s a way to avoid defenses and missile warning systems,” he said.

As the Financial Times reported initially, U.S. Air Force General Glen VanHerck, head of both U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM) and the U.S.-Canadian North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), had said at a separate conference in August that the Chinese had “recently demonstrated very advanced hypersonic glide vehicle capabilities” that present “significant challenges to my NORAD capability to provide threat warning and attack assessment.”

The U.S. military has observed “dog-leg maneuvers just right off the bat, maneuvering in space, what I call range-extensions,” U.S. Navy Vice Admiral Jon Hill told members of Congress back in June, before the reported Chinese test, in reference to advanced ballistic-missile performance capabilities in development around the world. “They’re all hypersonic when they come back into the atmosphere.”

A Chinese FOBS program, which appears to be in a very early stage of development and far from being an operational reality, would also be well in line with the rest of the country’s apparent strategic buildup, which includes what appears to be a dramatic expansion of its silo-based ICBM force, as well as the development of new air-launched capabilities and a growing fleet of nuclear ballistic-missile submarines. The U.S. government has repeatedly said in recent years that its intelligence shows that the Chinese are working to significantly enlarge their overall stockpile of nuclear warheads, as well.

The regime in Beijing has historically been and continues to be, at best, limited when it comes to transparency around its strategic capabilities and the policies that go with them. Drew Thompson, a former U.S. Department of Defense official with experience working on China issues, Tweeted out yesterday that Chinese officials may be increasingly more flexible about the nature of the country’s so-called “no first-use” policy” that ostensibly prohibits using nuclear weapons in response to non-nuclear threats.

Though technical developments such as the FOBS appear to be driven in no small part by a desire to respond to American missile defenses, the rest of this buildup is likely a product of a wider array of factors. It is especially important to point out that present and planned U.S. ballistic missile defenses cannot feasibly defeat a full-scale strike from China’s existing nuclear arsenal.

U.S.-Chinese relations have been increasingly cold for years now over a number of issues, including territorial and trade disputes. American criticism of the Chinese government’s handling of the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, its crackdowns on the Uyghur ethnic minority in its far-western Xinjiang province and on pro-democracy advocates in Hong Kong, and its increasingly threatening rhetoric and actions toward Taiwan, have all further fueled this deterioration in ties, while generating more support for hardline policies in Beijing. U.S., Chinese, and Taiwanese officials have increasingly spoken about fears of the inevitability of some kind of open conflict in the region.

“US missile defense remains the primary technical-level concern for China’s nuclear establishment” but “US efforts such as to strengthen ties with Taiwan and point fingers on China over Xinjiang might play a more direct role than US missile defense in fueling China’s accelerated nuclear modernization,” Tong Zhao, a Senior Fellow at the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy’s Nuclear Policy Program, wrote on Twitter as part of a longer discussion of possible Chinese strategi motivations.

With all this in mind, the U.S. government has expressed interest in negotiating new arms control deals with its Chinese counterparts, including possible tripartite agreements that would also include Russia. The Chinese, for their part, have rebuffed these overtures so far.

All told, a Chinese FOBS program, combined with a general lack of transparency regarding other strategic weapon developments, only adds further uncertainty to this already highly charged geopolitical environment.

Updated 5:45 PM EST:

NPR‘s Geoff Brumfiel has added some interesting data points to the discussion surrounding this reported orbital bombardment system test. The Financial Times reported that the Chinese Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology, or CALT, announced what it said were the 77th and 79th launches of Long March 2C carrier rockets, but that it did not issue any statement regarding the 78th launch. Brumfiel notes that CALT also did not announce the 76th Long March 2C launch, but that one does appear in a separate public database that CASC maintains of all launches involving any variant of the Long March family. Interestingly, CASC’s database does not show any gap that would align with the apparently missing 78th Long March 2C launch in CALT accounting.

Brumfiel also noted that CASC declining to say what rocket was used to launch the spaceplane in the July test only adds another layer of potential confusion. The discrepancies between the CASC and CALT accounting of total launches only raise more questions about the timeline of both the reported suborbital spaceplane and orbital bombardment system tests.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com