Hypersonic weapons are among the most difficult aerial threats to counter, and U.S. military leadership has for years been warning that these weapons could change warfare forever. One of the reasons this is the case is that they can outrun and outmaneuver almost all existing missile defenses. Even those that have a shot at swatting them down only do so via a tiny engagement window. To try and fill the hypersonic missile defense gap, a new report published this week has claimed that clouds of small particles in the sky, what the authors call “twenty-first century flak,” could help better defend against hypersonic threats.

A new white paper published by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, an independent think tank in Washington, D.C., advocates that the United States government put more resources into hypersonic weapons defense and explore novel approaches for defeating these new threats. CSIS’s new report is titled Complex Air Defense: Countering the Hypersonic Missile Threat and is authored by Tom Karako and Masao Dahlgren. The full report can be read online here.

Throughout the white paper, the authors argue that because many current ballistic missile defense systems are not equipped to defend against newer hypersonic threats, new missile defense approaches are needed that “should exploit hypersonic weapons’ unique vulnerabilities and employ new capabilities” to defeat them.

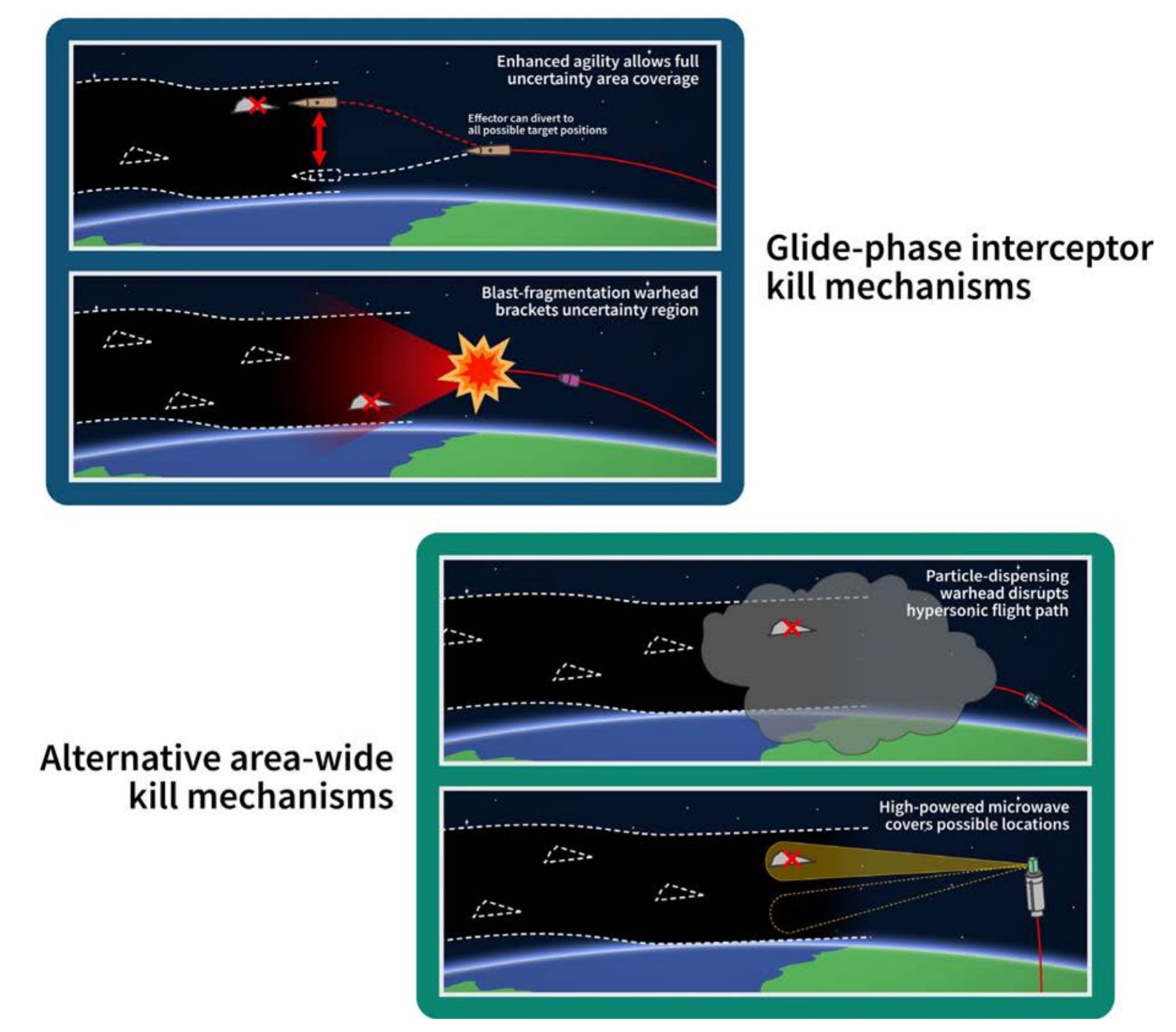

An entire chapter of the report, “Exploiting New Failure Modes,” explores a few novel approaches that may be able to achieve this. One of the most interesting proposals in the chapter outlines several concepts for “area-wide kill mechanisms” that could fill the air ahead of a hypersonic weapon’s flight path with small particles or high-power microwaves in order to degrade its performance or lead to “outright catastrophic failure.”

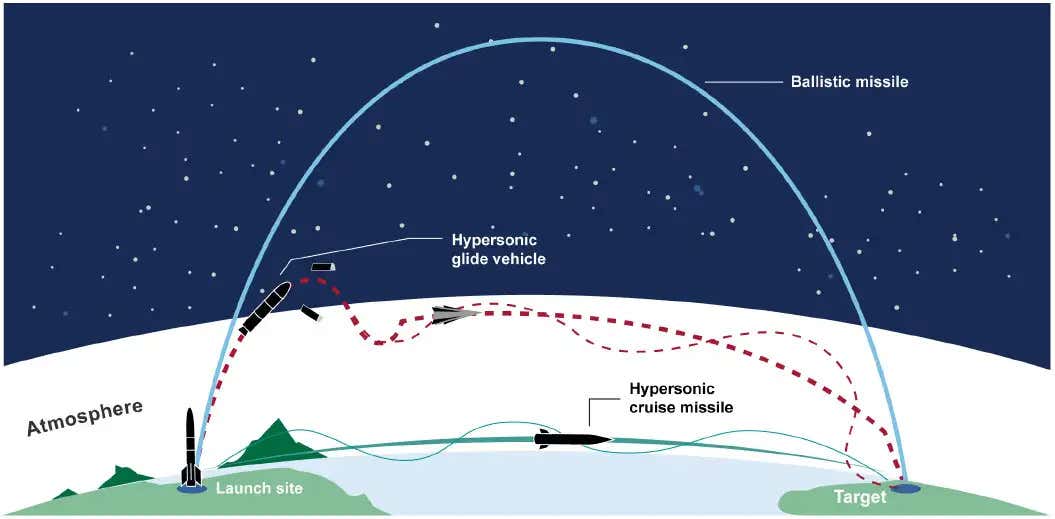

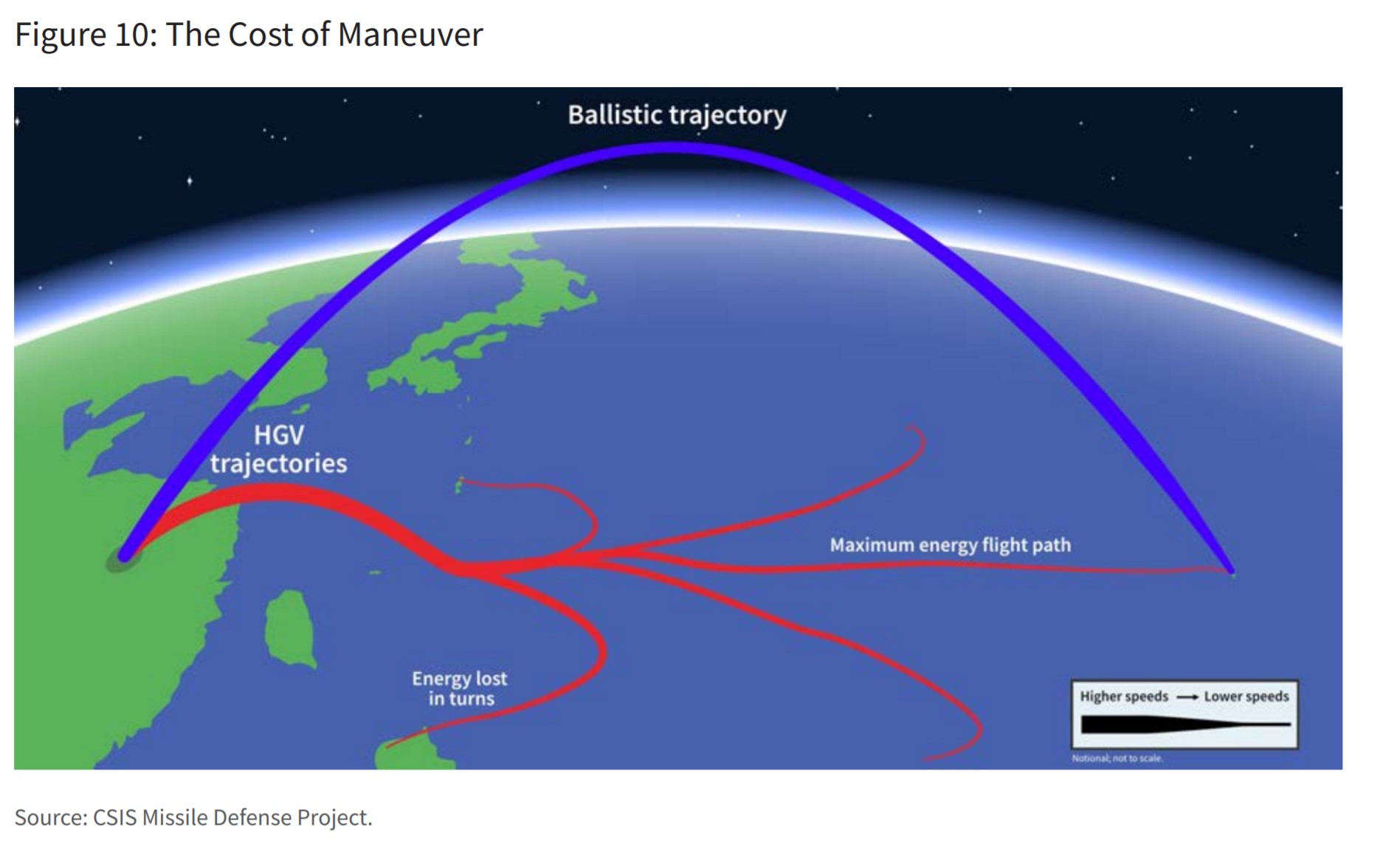

One of the main challenges associated with defending against hypersonic weapons is what the authors call the “violence of the hypersonic flight regime.” Unlike ballistic missiles which tend to fall along arcing, predictable trajectories from outside the atmosphere, unpowered hypersonic boost-glide vehicles fly at much lower altitudes and have the ability to execute abrupt maneuvers mid-flight. There are also air-breathing hypersonic cruise missiles that fly at even lower altitudes than boost-glide vehicles. Because both of these fly within the atmosphere along these lower, flatter trajectories, they are below the radar horizon of many ballistic missile early warning systems and are much more difficult to detect without sophisticated space-based sensors.

While the Missile Defense Agency, or MDA, has recently laid out its vision for how to defend against new hypersonic missiles, some of the technologies needed to achieve this layered defense system are still in development and could be many years away.

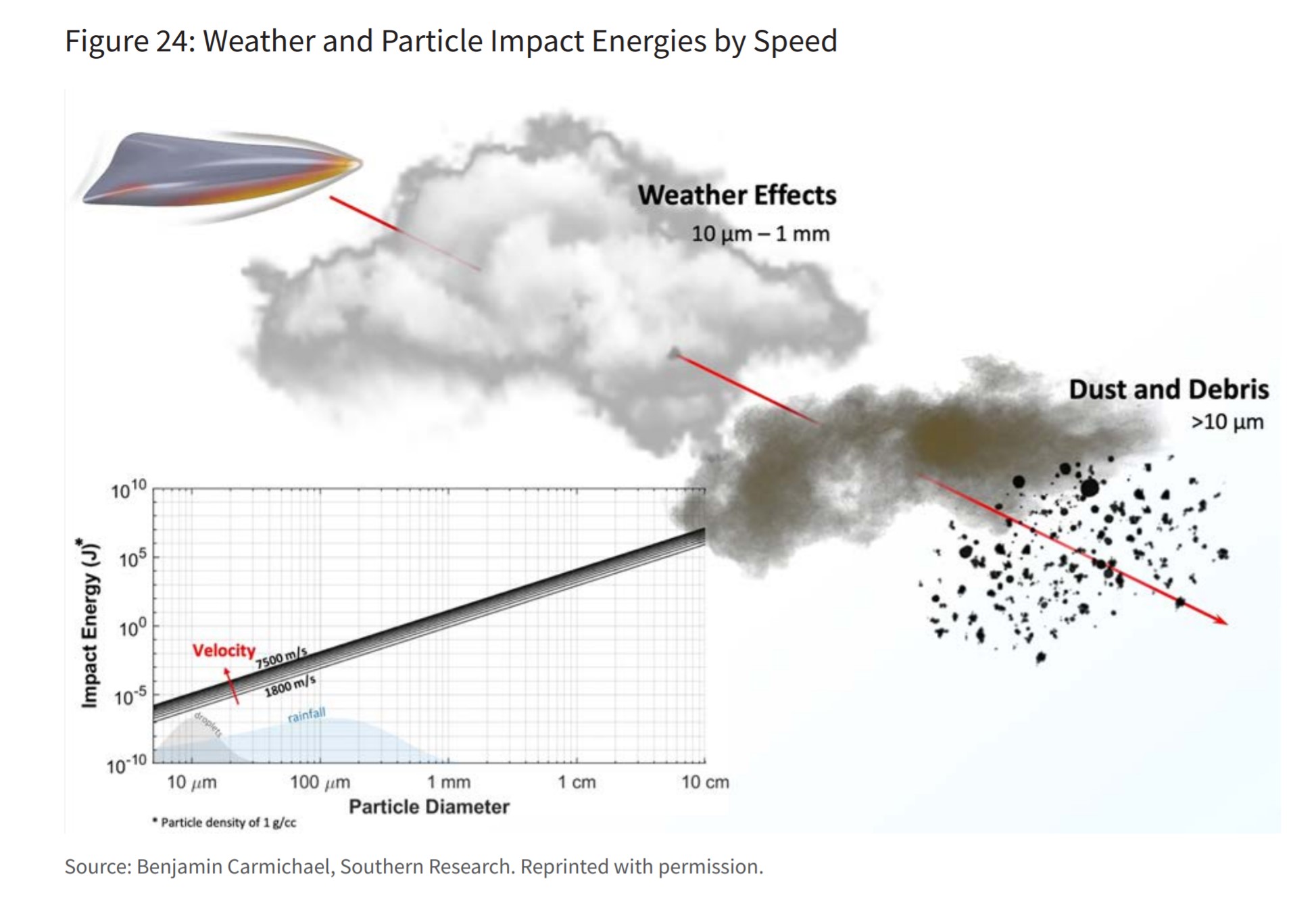

To help fill the hypersonic missile defense gap, the authors of this new CSIS report write that what may be needed is a form of “twenty-first-century flak.” At the extreme speeds at which hypersonic vehicles fly, impacts with even tiny particles in the atmosphere can create “bullet-like kinetic energies” and cause structural damage or unpredictable aerodynamic or thermal effects. Such a concept that fills the sky with tiny particulates would not have to destroy a hypersonic weapon outright but could instead simply alter its performance or trajectory enough to render it incapable of reaching its intended target. Obviously, deflecting a hypersonic weapon armed with a conventional warhead would be far more useful than doing so against one armed with a nuclear one, which could still cause significant damage even miles off-target.

The term ‘flak’ appeared during World War Two and is derived from the German word for “aircraft defense cannon.” Throughout the war, Nazi Germany relied heavily upon 88mm anti-aircraft guns that fired rounds that would explode into clouds of metal fragments, leaving behind thick black plumes of smoke hanging in the air. The shrapnel from each of these blasts could spread over hundreds of yards, meaning anti-aircraft crews would not have to achieve a direct hit to disable an aircraft and instead would literally fill the sky with clouds of these shrapnel bursts. The National Museum of the Air Force reports that often, aircrews would jokingly report flying through “flak so thick you could get out and walk on it.”

The “twenty-first-century flak” concept could work in much the same way but with a higher degree of sophistication. CSIS’s report describes how air defense systems could deploy “engineered particles” throughout a broad area of airspace close to a hypersonic missile’s trajectory early in its flight. These particles could be metallic or even pyrotechnic in nature and could be engineered to hang in the upper atmosphere for “tens of minutes,” offering a much larger window for engaging hypersonic weapons early in their trajectories. “Given the higher speeds earlier in the flight of a hypersonic glider,” the authors write, “a ‘wall of dust’ would be more effective earlier rather than later in its flight.”

The CSIS report cites several older studies conducted by the Space and Missile Systems Organization (now Space Systems Command) which discovered that dust, rain, and other particles in the atmosphere removed significant amounts of nose tip material from reentry vehicles when at high speeds. Such defensive concepts could even “compel adversaries to employ more conservatively designed, heavier, or lower-performance hypersonic systems” in response to this concept.

Aside from the hypersonic flak concept, the report also touches upon the current state of the art in directed energy weapons and examines how the two most common forms of these, lasers and high-powered microwaves, might perform in defense against hypersonic weapons. While the beam power of contemporary laser systems continues to increase, the CSIS white paper points out that “even the hundred-kilowatt to megawatt-class powers expected of future laser systems may not be adequate for penetrating hypersonic thermal protection systems.”

High-powered microwaves, or HPM, on the other hand, show more promise. Both the Navy and the Air Force have explored using HPM for a variety of defensive applications. These systems work by transmitting powerful bursts of microwave energy that can disrupt or destroy electronics inside of a vehicle or missile. CSIS notes that HPM systems have a more limited range than lasers, and could possibly still need to be deployed alongside kinetic interceptors which could destroy weapons once their guidance and control circuitry is damaged by microwaves. Still, these systems do not require the sophisticated targeting systems that lasers do and are far less susceptible to adverse weather conditions.

Because of these factors, the report’s authors argue that HPM weapons could rely on even relatively imprecise sensor data to “fry the sky” ahead of hypersonic weapons and essentially create a type of electromagnetic ‘flak’ that could target a wide area through which a hypersonic weapon is projected to travel. There are challenges to this approach, of course, and the report adds that “successful employment of HPM weapons may hinge on insights gathered from the United States’ own strategic weapons efforts and technical intelligence on foreign systems.”

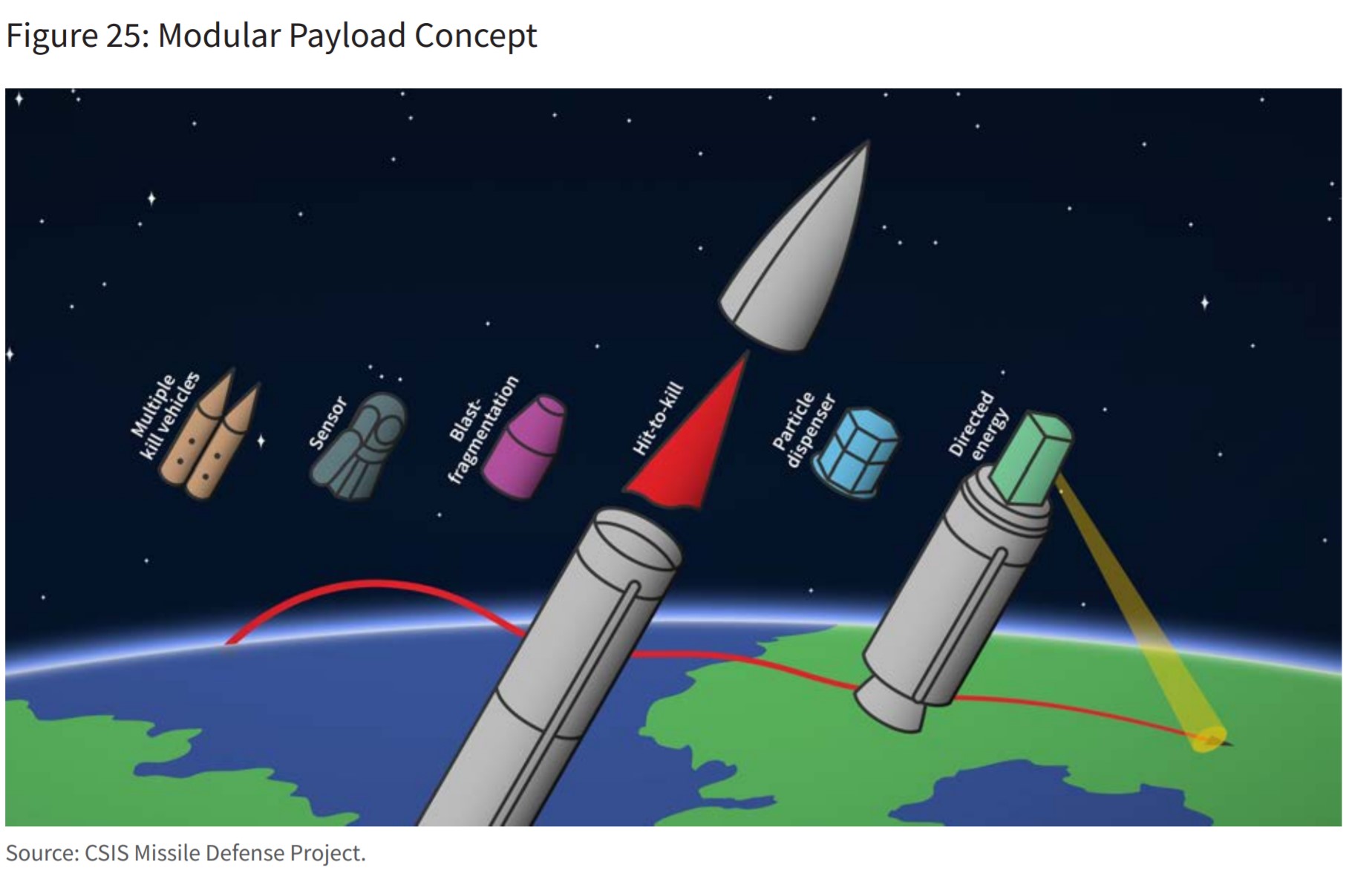

Additionally, the CSIS report describes what it calls “modular payloads,” interceptors or other platforms which incorporate multiple payload types into one common booster system. A single booster could contain directed energy weapons, blast fragmentation explosives, particulate “twenty-first century flak” warheads, kinetic interceptors, or even additional sensors all at once. These multi-pronged payloads could offer a layered system that could engage hypersonic threats at multiple points in their trajectories and with different approaches at each one.

Each layer in these modular payloads wouldn’t even necessarily need to be fatal to the hypersonic vehicle, but could work together with other layers to cumulatively degrade a hypersonic threat and achieve a mission kill. Furthermore, incorporating multiple types of payloads in a single booster system could “create doubt about which modalities an attacker needs to overcome, and from where.”

Even within these modular multi-layered payloads, the report’s authors argue that the flak-like “particulate warheads” they envision could outpace any potential adversaries’ abilities to develop countermeasures against them:

New varieties of particulate warheads, for example, could be fielded at a faster pace than new hypersonic weapons, imposing costs on an aggressor. Without the exquisite demands of “detect-control-engage,” area-wide particulate defense could positively affect the cost curve. Payloads could be developed with different densities, volumes, and pyrotechnic, incendiary, or corrosive characteristics, with dispersion patterns optimized to defeat an evolving threat. Hardening a hypersonic weapon against marginal changes in particle characteristics could require an extensive system engineering effort given the deep level of integration inherent in hypersonic weapon design.

From what we can tell, the primary intercept concepts for hypersonic defense that the US has been exploring involves either traditional interceptors with high-explosive warheads like the Navy’s SM-6 (RIM-174) missile or new hit-to-kill style interceptors that require directly impacting their targets. Either method requires incredibly precise and sophisticated targeting against a threat that is moving erratically and at extreme speeds. Shooting down ballistic missiles has often been described as ‘trying to hit a bullet with another bullet,’ and intercepting hypersonic missiles or glide vehicles is even more difficult. The types of “particulate warheads” described by CSIS could potentially increase hit probability of hypersonic intercepts and reduce the cost-per-intercept since one would imagine that the guidance required for placing a cloud of debris along a vehicle or missile’s projected path would be lower than trying to actually smash into a moving hypersonic vehicle.

Any potential area-effect intercept capability could also help defend against multiple incoming threats or discriminate between decoys or similar countermeasures. With a wide-area cloud of particulates, there is less of a need to strike individual targets or prioritize a single interceptor for a particular target.

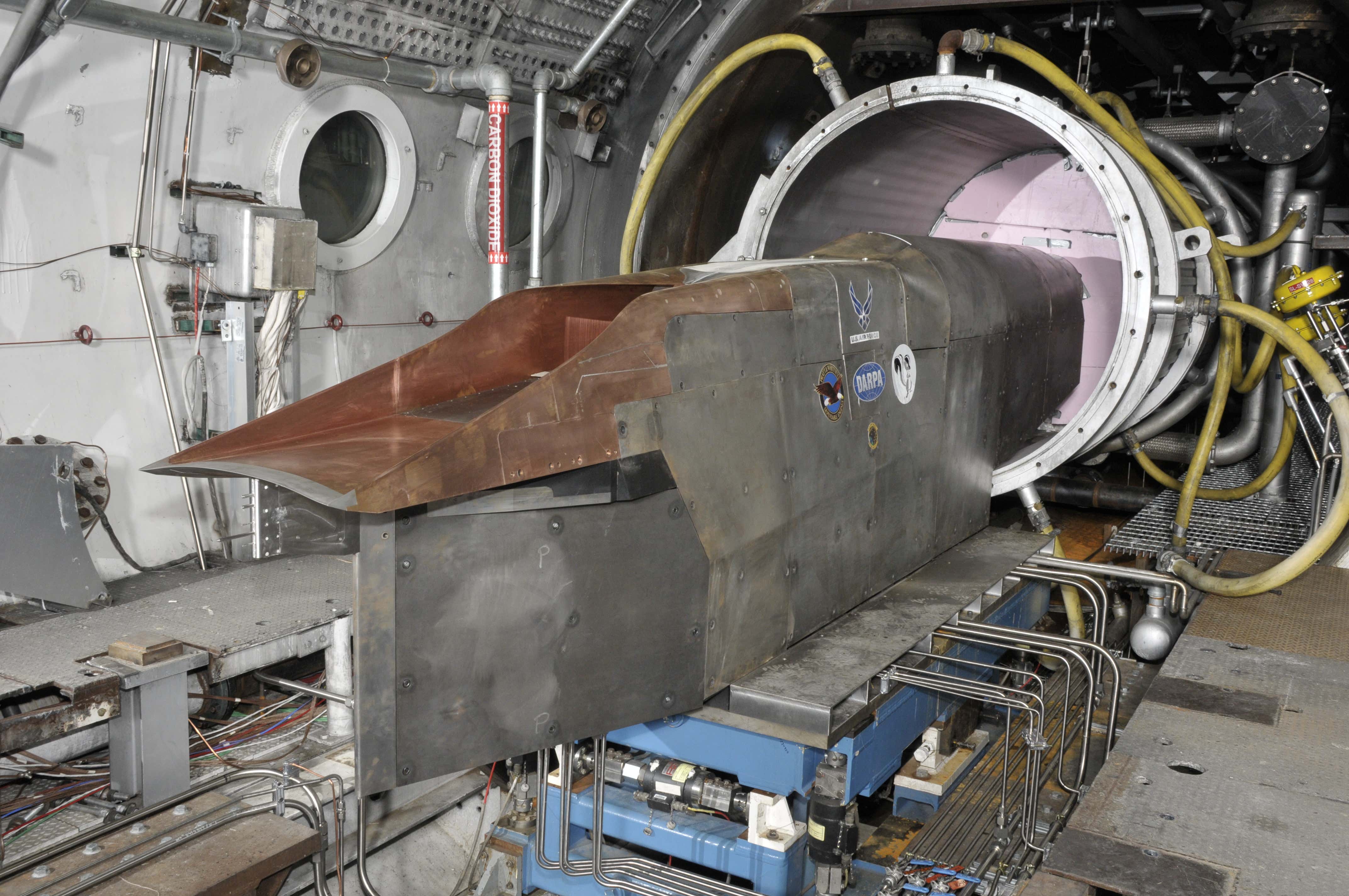

The overall effort to develop and field new defense technologies could be hindered by an overall lack of hypersonic testing facilities, though. Any new directed energy or wide-area intercept concepts would obviously need to be tested for their efficacy and in different combinations. Mark Lewis, former acting secretary of the Pentagon’s Office of Research & Engineering and current head of the National Defense Industrial Association’s Emerging Technology Institute, said this week that the United States’ hypersonic testing infrastructure is “frankly, right now inadequate.”

However, Lewis also adds that just because there is little information available to the public concerning hypersonic weapons and defenses, that doesn’t mean there isn’t extensive research and development occurring in the classified world. “Not seeing something doesn’t necessarily mean it isn’t happening,” Lewis told Breaking Defense.

The “twenty-first-century flak” concept is still highly theoretical, at least as far as we know, and the authors of the new CSIS report note that for the time being, “the most important efforts remain the sustainment and effective fielding of a space sensor layer and glide phase kinetic interceptor.” Those two technologies are currently being developed by the Missile Defense Agency and associated contractors.

Ultimately, even though the wide-area particulate warhead concept remains unproven and has not been demonstrated, at least publicly, it helps illustrate the larger challenges associated with finding new ways of defeating this emerging class of threats. More agile interceptors are needed to defeat maneuvering hypersonic glide vehicles and hypersonic cruise missiles, and until those are successfully fielded, outside-the-box concepts like “twenty-first-century flak” could offer a new approach to helping defend against hypersonic weapons.

Contact the author: Brett@TheDrive.com