The Missile Defense Agency, together with the U.S. Navy, plan to test an SM-6 missile against an “advanced maneuvering threat,” a term that has been used in relation to unpowered hypersonic boost-glide vehicles, later this year. The Pentagon says that unspecified versions of the SM-6 have already demonstrated some degree of capability against these types of weapons, examples of which Russia and China have already begun putting to service. A new variant of the SM-6, the Block IB, is already under development and will itself be able to reach hypersonic speeds.

Barbara McQuiston, a senior U.S. official currently performing the duties of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, including mention of the scheduled SM-6 test in her testimony before the Senate Appropriations Committee’s Subcommittee on Defense yesterday. The aim of the hearing was to give Senators on the subcommittee an update on Department of Defense innovation and research efforts, broadly.

“MDA [the Missile Defense Agency], in cooperation with the U.S. Navy, demonstrated early capability against maneuvering threats during flight-testing of the Standard Missile (SM)-6 Sea-Based Terminal (SBT) defense, and it will further demonstrate this capability against an advanced maneuvering threat-representative target later this year,” according to McQuiston’s written testimony. “We will continue to advance our SBT capability to address the regional hypersonic threat and will test that capability in the FY 2024 timeframe.”

As noted, the phrase “advanced maneuvering threat” has previously been used in relation to hypersonic boost-glide vehicles. Russia has at least one such weapon, Avangard, in limited service now, as does China, with the DF-17. China is also developing other weapons in this category, possibly including an air-launched type for its H-6N missile carrier aircraft.

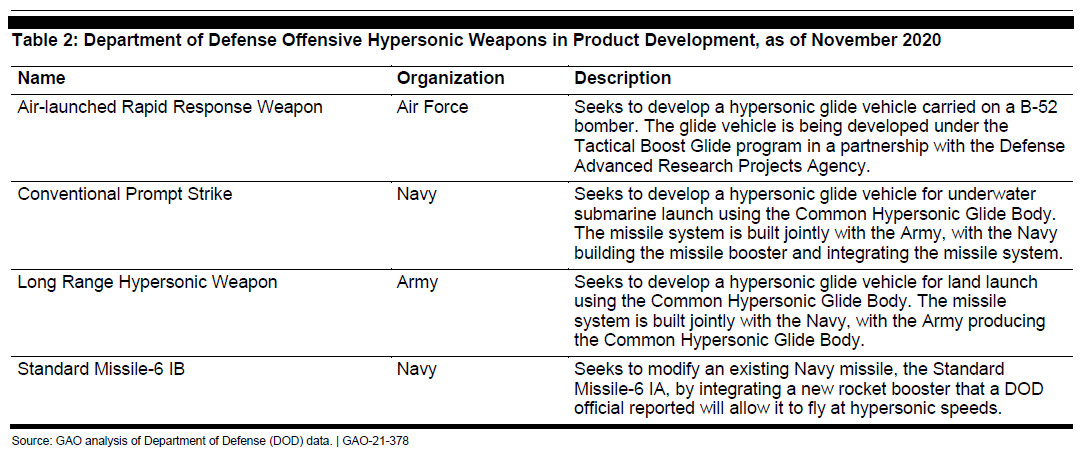

There is growing interesting in boost-glide vehicles elsewhere in the world, as well, including in the United States, where the U.S. Air Force, Army, and Navy are all in the process of developing their own designs. MDA has already been involved in U.S. hypersonic weapon testing, collecting data to support counter-hypersonic projects.

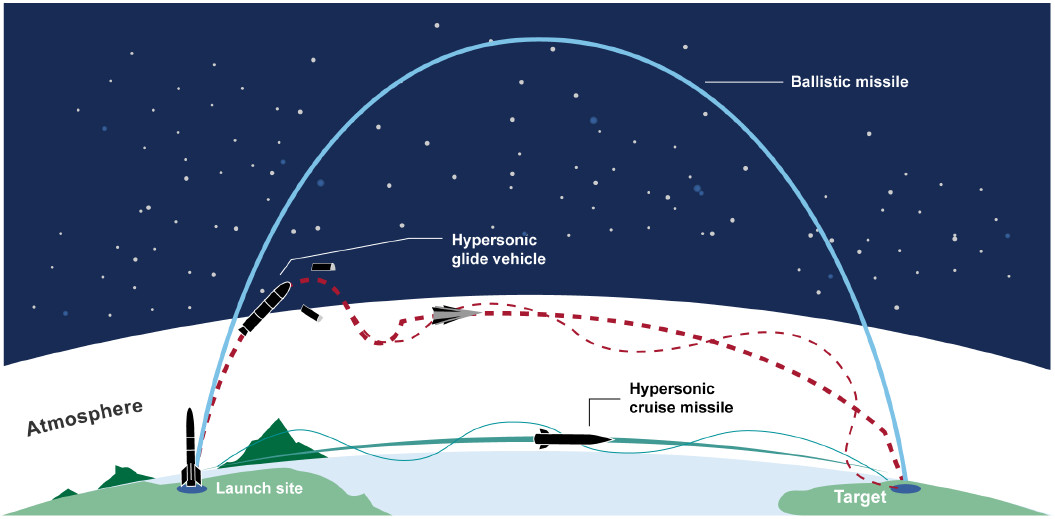

Unpowered boost-glide vehicles use a rocket motor to get them to an optimal altitude and speed. At that point, the vehicle detaches and glides down to its target at hypersonic speeds, defined as anything above Mach 5, along an atmospheric trajectory.

Boost-glide vehicles are designed to make very unpredictable movements during their flights compared to traditional ballistic missiles, even ones with maneuverable reentry vehicles. As a result, the hypersonic weapons present significant challenges for enemy air and missile defenses, even particularly dense defensive networks protecting high-value targets. The combination of speed and maneuverability makes these weapons difficult to spot and track, and reduces the overall amount of time available to react in any way, including simply trying to move critical assets out of the target area or otherwise attempting to seek cover.

More conventional ballistic missiles with increasing degrees of maneuverability, including air-launched types, such as Russia’s Kinzhal, also reach hypersonic velocities in the terminal phase of flight and present their own form of “advanced maneuvering threat.” Air-breathing cruise missiles able to reach hypersonic speeds and maneuver erratically at low altitudes present another emerging concern.

This is not the first time the Pentagon has publicly discussed using a variant of the SM-6 for hypersonic defense. In March 2020, Mike Griffin, then the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, first revealed that this missile was among those being considered for this role and that there were plans to test one of them against an actual hypersonic boost-glide vehicle sometime in the 2023 Fiscal Year. It’s not clear whether the test Griffin was referring to is the one now scheduled for this year or the one that MDA now plans to carry out in the 2024 Fiscal Year.

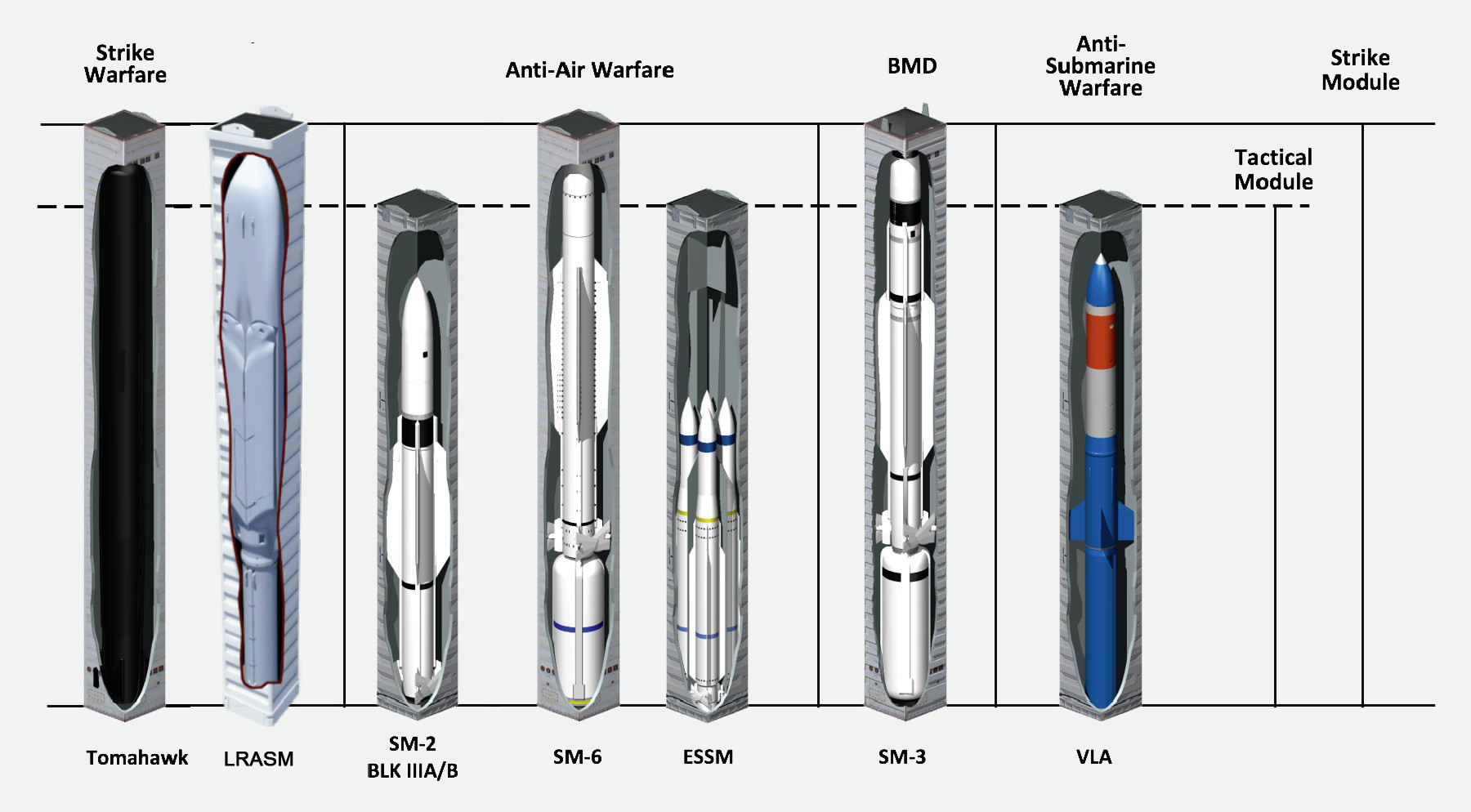

Just days before Griffin made his remarks last year, Navy Vice Admiral Jon Hill, director of MDA, had also said that the interceptor being developed under the Regional Glide Phase Weapon System (RGPWS) program would fit inside Mk 41 Vertical Launch System (VLS) launch cells. The SM-6 is designed to be fired from Mk 41 VLSs with longer “strike-length” cells.

In her written testimony, McQuiston mentioned “a newly designated Glide Phase Intercept initiative to develop a capability to defeat a regional hypersonic threat.” It’s not clear how this new effort relates to the earlier RGPWS program. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency has also been exploring counter-hypersonic capabilities through its Glide Breaker program.

It’s also not clear what variant or variants of the SM-6, which is also known as the RIM-174 Standard Extended Range Active Missile (ERAM), MDA plans to employ in any of these future hypersonic defense tests. The original SM-6, which entered service in 2013 as a new weapon for Navy warships equipped with the Aegis combat system, is a highly-capable missile, as you can read about in more detail here. It can be employed against aircraft and low-flying cruise missiles and has the ability to knock down certain kinds of ballistic missiles in the terminal phase of their flight – the same SBT role that McQuiston references in her testimony.

The SM-6 has a nascent surface-to-surface capability, as well. The Block IA version of the missile adds a GPS-assisted guidance option to expand its ability to hit static surface targets. Both the Block I and Block IA variants have two-way data links that allow them to get updated targeting information in flight from both the ship that launched them and offboard platforms.

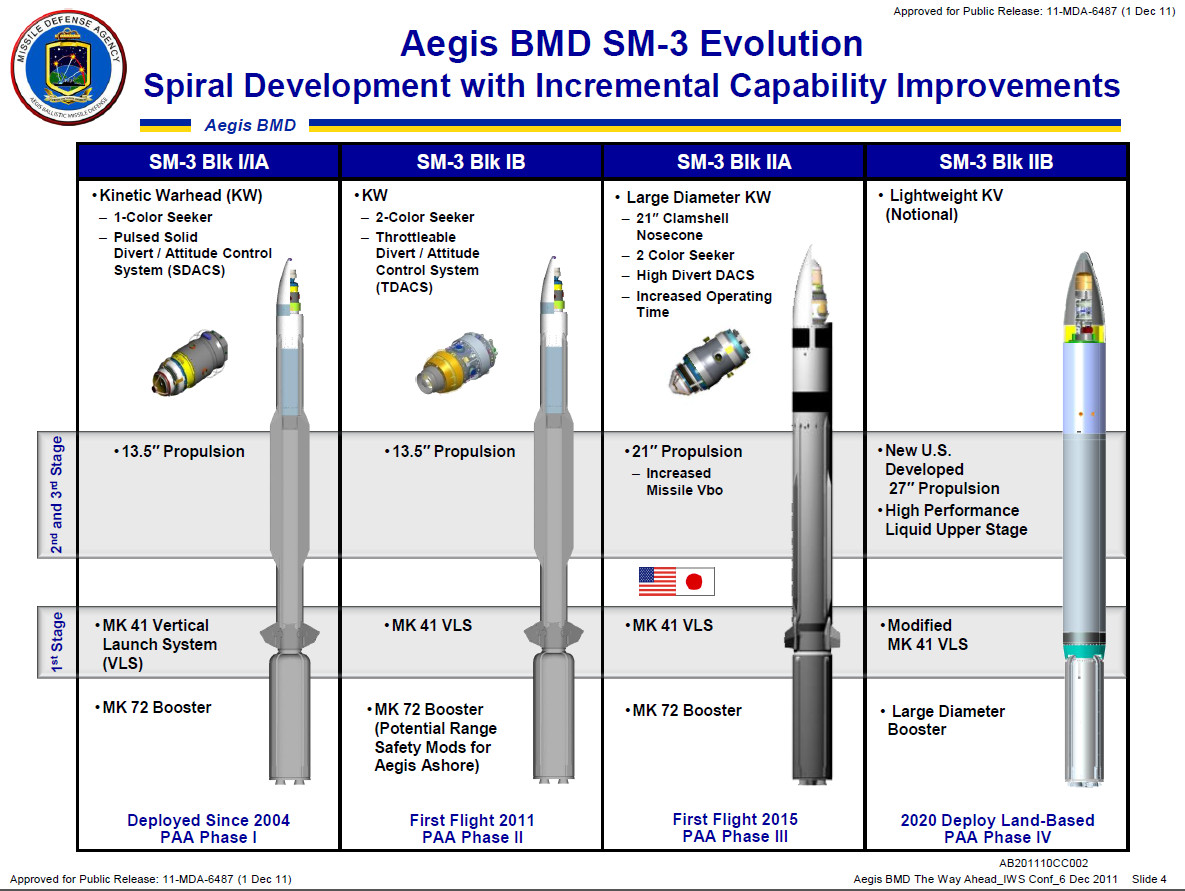

In 2019, the Navy disclosed additional plans for a Block IB version of the SM-6 that would mate the guidance system and other components of the Block IA to the enlarged missile body used on the SM-3 Block IIA missile. The SM-3 Block IIA is designed to engage ballistic missile threats in the mid-course portion of their flights when they are flying at extremely high altitudes.

It is the still-under-development Block IB version of the missile that would seem best suited to hypersonic defense. A report on U.S. hypersonic weapons development programs that the Government Accountability Office (GAO), a Congressional watchdog, released in March confirmed earlier reports that this variant will fly at hypersonic speeds.

An SM-6 variant would also be a good starting place for developing a hypersonic defense weapon that could be used to protect assets at sea, as well as on land. The U.S. Army is already in process of evaluating a land-based version of this missile as a longer-range strike weapon. The Navy could potentially integrate advanced SM-6s into existing and future Aegis ashore missile defense sites, as well.

If the hypersonic defense version of the SM-6 remains similar, if not largely identical, to an existing variant, such as the Block IB, the missile could remain an extremely flexible weapon that ships or ground-based launch platforms could still employ against a wide range of other targets, as well. It’s certainly not hard to see how one variant might offer a single line of defense against hypersonic boost-glide vehicles, as well as air-breathing hypersonic cruise missiles and advanced ballistic missiles.

At the same time, questions remain about just how effective any kind of interceptor will ever be against hypersonic threats. “Directed energy weapons (high energy lasers or particle beam) or space-based interceptors provide the best overall hope of a hard kill,” the NATO Science & Technology Organization said in a March 2020 report, which seemed to imply the possibility of a successful interception of a hypersonic weapon was low, in general.

Clearly, the forthcoming tests of the SM-6 in the counter-hypersonic role are meant to prove that a version of this weapon will indeed offer valuable additional protection against these emerging advanced threats.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com