The U.S. Air Force is still working to iron out just what it thinks air-to-air combat will look like a decade from now and what types of aircraft it will need to come out on top in any future fight. As part of its ongoing Next Generation Air Dominance program, or NGAD, the service is exploring a wide array of manned, unmanned, and pilot-optional concepts, as well as advanced associated technologies, including increased network connectivity and autonomous capabilities. At the same time, however, it has steadily moved away from plans for a once much-touted sixth-generation fighter jet.

A number of senior Air Force leaders have offered updates about NGAD recently, all of who stressed that the final force mixture will include a variety of different platforms, as well as munitions and other systems, all tied together at various levels. This could include manned aircraft networked together with “loyal wingman” drones, fully autonomous unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAV), swarms of low-cost unmanned aircraft, and more.

“If we were to characterize it [NGAD] as a fighter, we would be… thinking too narrowly about what kind of airplane we need in a highly contested environment,” U.S. Air Force Major General Scott Pleus, who is currently Director of Air and Cyber Operations for Pacific Air Forces, recently told Air Force Magazine. “A B-21 [Raider stealth bomber] that also has air-to-air capabilities” and can “work with the family of systems to defend itself, utilizing stealth – maybe that’s where the sixth-generation airplane comes from.”

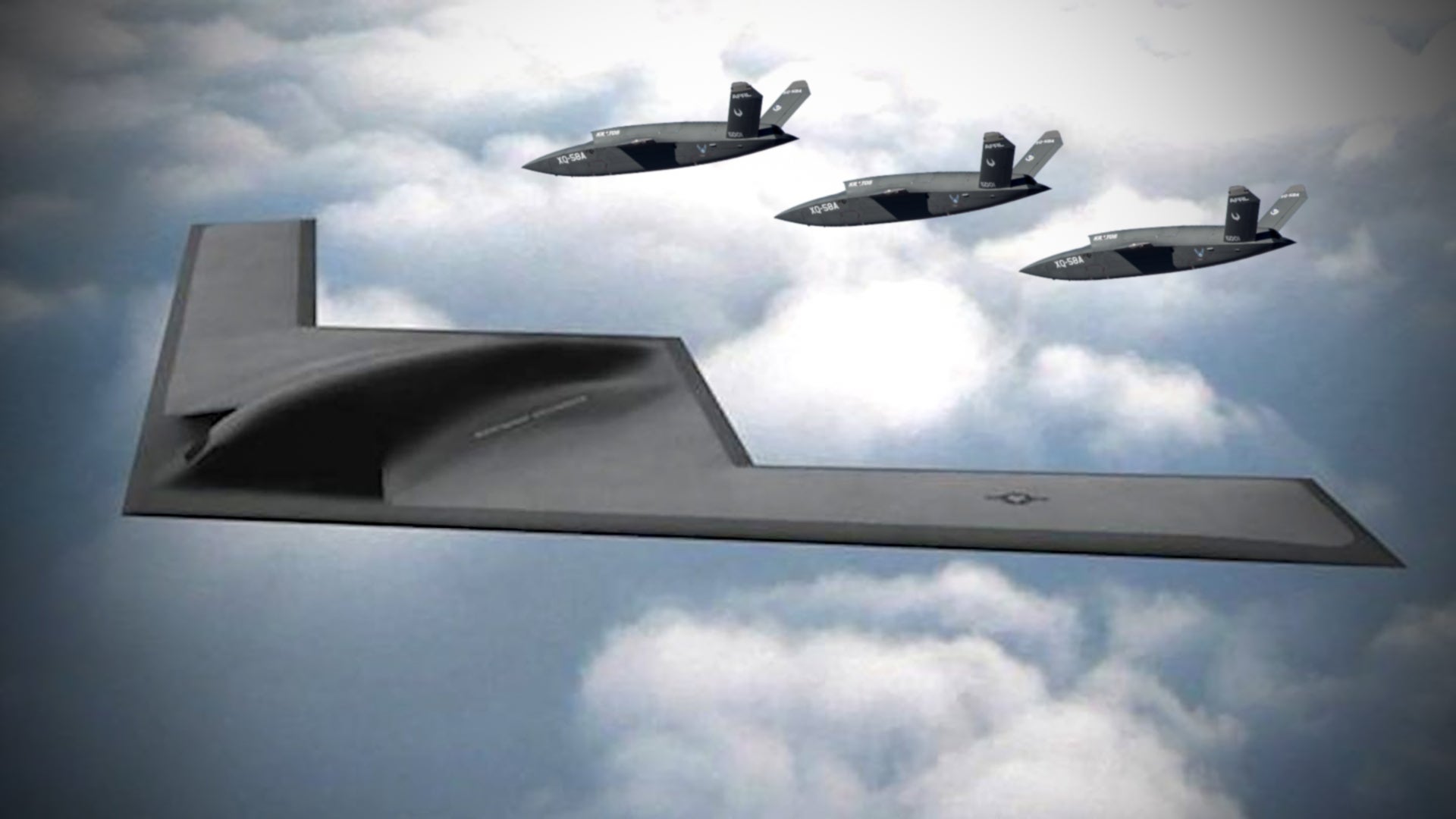

The Air Force Research Laboratory released the video below in 2018, which shows various notional advanced capabilities, including a manned sixth-generation fighter jet and loyal wingman drones, which could be in service in the 2030 timeframe.

It’s not clear if he literally meant an aircraft as large as a B-21 Raider, or the B-21 Raider itself, acting as a manned component of the Air Force’s future air-to-air combat ecosystem or if he was simply referring to repackaging the stealth bomber’s state-of-the-art features and capabilities in something like a very stealthy unmanned combat air vehicle (UCAV). However, The War Zone

has pored over the available information about the B-21 on a number of occasions and explored how the bomber itself could serve in multiple roles, including in an air-to-air capacity.

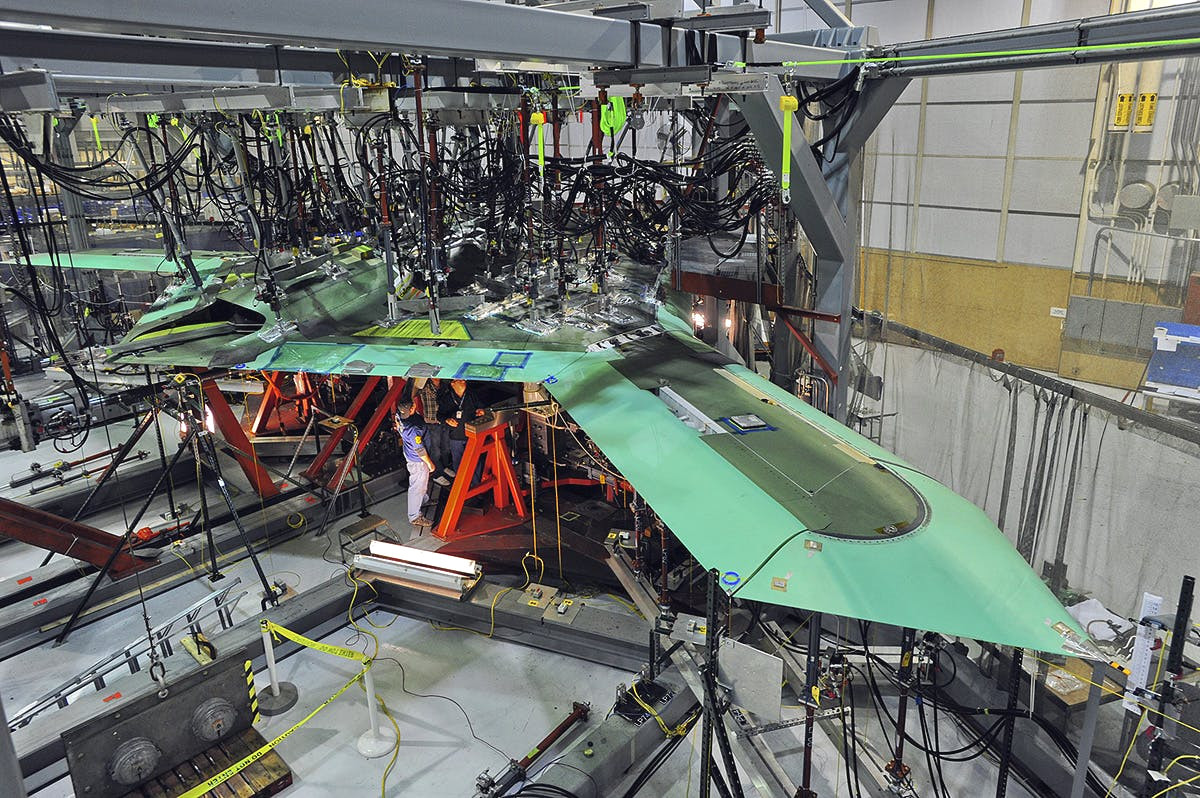

A tailless, stealthy, comparatively long-range tactical jet that many had labeled a sixth-generation fighter had been the focus of the Air Force’s plans for dominating the air-to-air realm through the middle of the century up until recently. The fiscal realities of producing such an aircraft that would require a long development period would have made it very unlikely to materialize even before the USAF shifted its focus on the matter. If anything, a heavily upgraded “F-35E” variant of the Joint Strike Fighter is far more likely to serve in the role of a future manned tactical fighter for the USAF based on fiscal constraints alone.

Case in point, in December 2018, the Congressional Budget Office released an assessment that the Air Force’s previously proposed Penetrating Counter Air aircraft could have an average unit cost of around $300 million, even with a relatively large order of more than 400 aircraft. This was more than three times the price the service was paying at the time for new F-35As. The unit costs of all three Joint Strike Fighter variants have since decreased further. This further reinforces the pipe dream that is developing and producing a ‘sixth generation’ fighter, at least in a traditional sense.

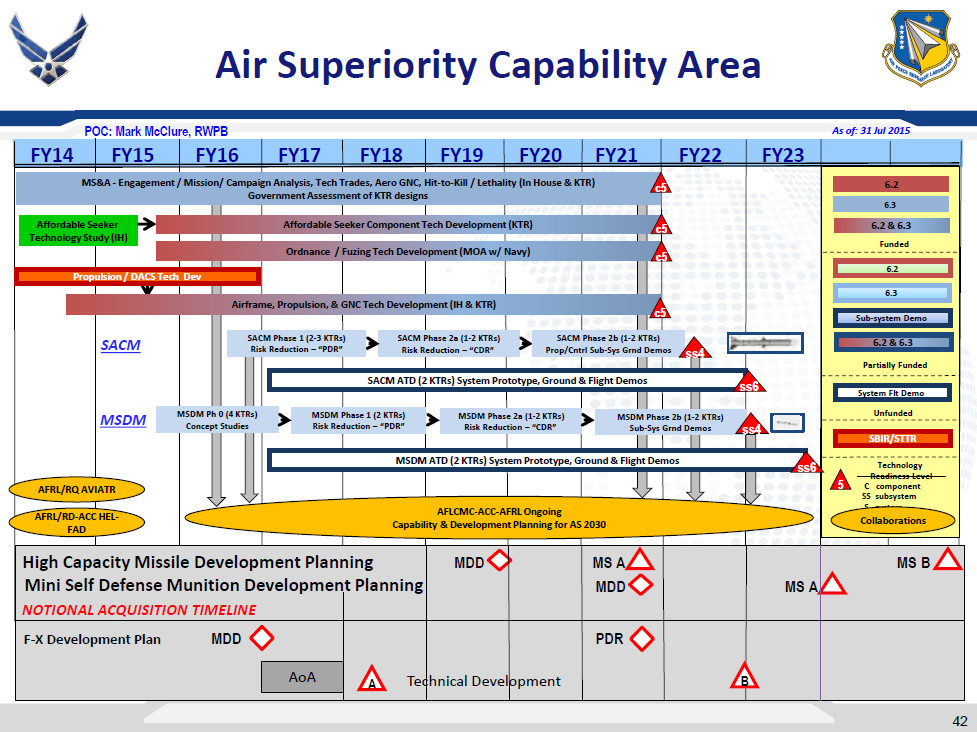

Regardless, the Air Force is still very much working out what it wants from NGAD, which traces its immediate roots back to at least 2015 with the start of an “F-X Development Plan.” The next year, the service published a study titled “Air Superiority 2030 Flight Plan,” which initially to a program called Penetration Counter Air (PCA) that, in turn, has evolved into the current effort.

The Air Force had planned to complete additional studies to determine its future air superiority requirements by mid-2018, but this ended up being pushed back to the middle of this year, according to a backgrounder from the Congressional Research Service. This would have brought it in line with parallel U.S. Navy efforts, which had also evolved from a future fighter jet concept, known as F/A-XX, and was sometimes confusingly also referred to as NGAD.

In this same time frame, the language surrounding the Air Force’s NGAD project has steadily moved away from talking about actually developing a new fighter jet. In April 2018, senior Air Force leaders told Congress they had recognized there was “no ‘silver bullet’ solution” when it came to developing a new air combat platform.

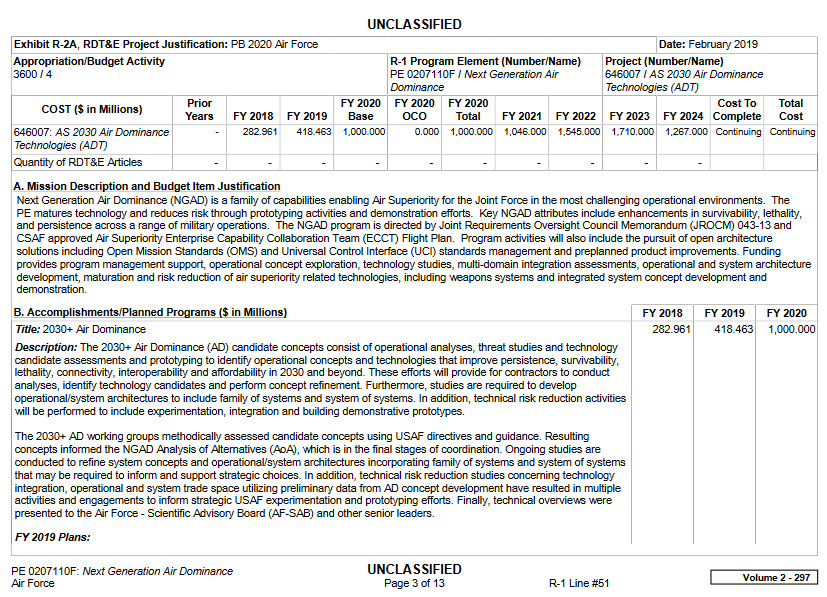

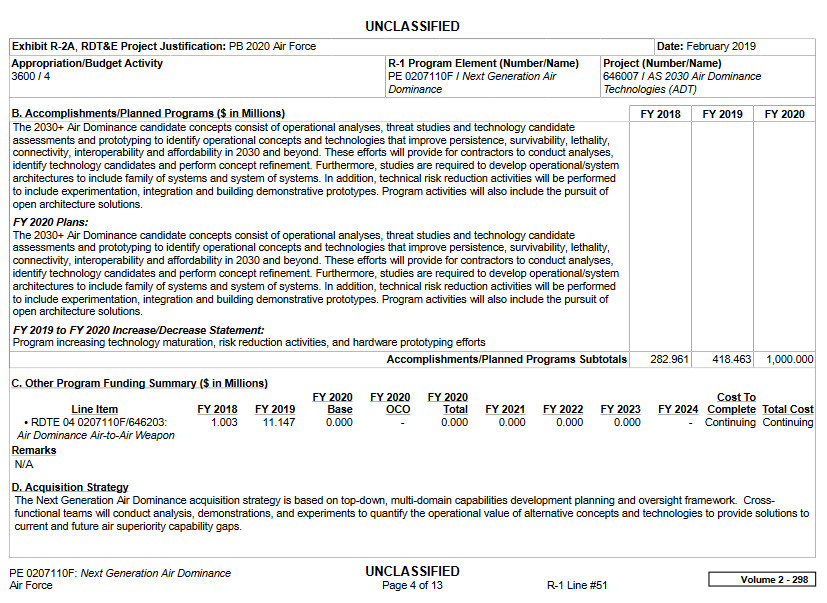

The Air Force’s latest budget request for 2020 Fiscal Year budget asks for more than $1 billion to conduct additional studies into both aircraft and weapon systems under NGAD. “The 2030+ Air Dominance candidate concepts consist of operational analyses, threat studies and technology candidate assessments and prototyping to identify operational concepts and technologies that improve persistence, survivability, lethality, connectivity, interoperability and affordability in 2030 and beyond,” the service’s budget documents say in outlining the plans for the upcoming fiscal cycle.

You can read the complete relevant sections from the Fiscal Year 2020 budget request below:

Of course, while the Air Force is clearly still very far from settling on any mix of platforms that will provide its future tactical air combat capabilities, there are some indications as to where the service’s general thoughts may be trending. PCA had initially focused heavily on some form of manned sixth-generation fighter jet, but as NGAD has evolved, it has steadily shifted more and more toward unmanned and pilot-optional concepts linked together by powerful networks so that they can operate at least semi-autonomously, if not autonomously, as necessary.

“[NGAD] really does diverge away from a platform-centric way of doing air superiority,” Major General Pleus

explained Air Force Magazine. “We’re going to have to up our game in all areas.”

In the future, manned aircraft may still act as limited, centralized forward controllers for the Air Force’s unmanned air combat fleets. At the same time, the Air Force is actively exploring systems that could potentially rapidly turn any aircraft into an autonomous platform as part of its Skyborg program. Though the Air Force has declined to confirm if this remains the case, the service had previously decided that the B-21 Raider itself would be pilot optional, as well.

The unmanned components of NGAD, whatever they turn out to be, may be more complex than just pure drones that may or may not be capable of working together with manned aircraft as “loyal wingmen,” too. An emphasis on modular physical structures, as well as software architecture, offers the possibility that a platform that begins in one form may quickly grow into one that can operate with or without crew and with or without any kind of direction from a manned aircraft or a ground station.

In addition, the line between aerial weapons and unmanned aircraft may also become increasingly blurry. For years now, the Air Force has been touting plans to develop and acquire fleets of unmanned aircraft that will be “attritable.” This is typically understood to mean that they are cheap enough to procure that commanders can use them in riskier ways without worrying about the costs to replace them, but it is not supposed to be a synonym for “expendable” or “disposable.” The prime example of such a system is Kratos’ XQ-58A Valkyrie drone, which the Air Force is now experimenting with.

This concept may be evolving, as Steve Trimble, Aviation Week’s Defense Editor and a good friend of The War Zone, noted from remarks that Acting Secretary of the Air Force Matt Donovan made at the third annual Defense News Conference on Sept. 4, 2019. The Air Force’s top civilian specifically talked about investments in “low-cost single-use aircraft” as part of NGAD.

As Trimble highlighted in a series of Tweets, this would not only mean that these platforms could be used in a disposable fashion, but that they would be, by definition, disposable after a single sortie. This would be a significant departure from the commonly accepted understanding of “attritable” and create a class of systems that would lie somewhere between highly networked munitions – something the Air Force is already working on through its Golden Horde program – and more traditional unmanned aircraft. Extremely long-range air-to-air missiles, even anti-aircraft cruise missiles, possibly traveling at hypersonic speeds, might fit this general description, as well, though the U.S. military does typically make hard distinctions between these types of weapons and anything it would define as an “aircraft.”

Beyond that, in 2017, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency did outline a concept for a “flying missile rail” that a combat aircraft would carry like a stores pylon, but that would then detach and fly away on its own like a miniature UCAV. This unmanned platform would then fire its missiles at the intended target, extending the overall engagement range of those weapons and their overall tactical flexibility.

Donovan may have also been referring to investments the U.S. military has already made into small, low-cost, disposable drones, which, so far, have been largely focused on logistical missions. Examples of this work would be DARPA’s Inbound, Controlled, Air-Releasable, Unrecoverable Systems (ICARUS) program and the U.S. Marine Corps’ Supply Glider effort.

There is also a possibility that Donovan could be referring at least in part to a broader concept of acquiring more aircraft faster, but with shorter life cycle expectancies. In April 2019, Will Roper, the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, proposed just such a concept and likened it to the service’s relatively fast development and acquisition of the “Century Series” fighter jets from the 1950s and 1960s. Those jets, which had designations beginning with F-100, hence the nickname, were not supposed to last for decades, though they weren’t supposed to be disposable either.

In 2018, now-retired U.S. Air Force General Ellen Pawlikowski, who was then head of Air Force Materiel Command, used somewhat similar language to describe the deliberate acquisition of aircraft with no long-term sustainment plan. These planes would not be disposed of after a single mission, but the service would still effectively plan from the beginning to throw them away at the end of a potentially short service life.

Roper’s and Pawlikowski’s concepts may be more in line with what Donovan actually meant with his description of planes that are “single use,” rather than platforms the Air Force plans to sustain and upgrade for decades. The goal here would be to encourage rapid development cycles and reduce the costs of initial acquisition of aircraft and establishing the supply chains necessary to support them in the long term.

None of these concepts are really all that original. In, 2016, The War Zone proposed all of them and many more in a highly detailed feature on unmanned air combat systems intended for a higher-end fight and why they had mysteriously disappeared from the Air Force’s nomenclature and public persona, which you can read here. You can also read about how many of these general ideas were becoming evident even longe before then.

In recent years, sustainment costs, broadly, have only become an increasingly serious concern for the Air Force, as well as the other branches of the U.S. military, especially when it comes to complex manned platforms, such as the F-22 Raptor and the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. Fleet size and the readiness of those fleets are also highly pressing issues. So, at least in the near term, it’s not surprising that NGAD may end up focusing more on exploring available lower-cost options with distributed capabilities as alternatives to traditional air combat assets with highly centralized capabilities, such as manned fighter jets packed with ‘exquisite’ technologies.

In the Air Force’s mind, “this is not going to be a 2040 version of the F-22, an aircraft that can close almost any kill chain the Air Force has today all by itself,” Steve Trimble, who has been actively following the evolution of the service’s aerial combat concepts, told The War Zone by Email. “This is going to be a family of aircraft, with each optimized to close one or two links of the chain. … In the near-term, of course, it will begin by pairing F-35As and F-22s with the XQ-58A as a Loyal Wingman. Over time – at least a decade or more – the Air Force hopes to transition to the new approach with capabilities dispersed among multiple types of networked aircraft.”

“It’s a concept that implies turning the aerospace industry upside down. Generally speaking, prime contractors today lose money on designing aircraft, break-even during development and production and make the real profits during sustainment,” he continued. “The Air Force wants contractors to put their focus mainly on cutting-edge design, then leave the production and sustainment phase open to competition. It’s the only way the Air Force can pump out new aircraft types every three years, rather than one every 15-20 years. And that approach also incentivizes industry to allow the Air Force to retire aircraft as soon as they become obsolete, rather than keep them propped up for decades with expensive incremental upgrades.”

At the same time, Trimble noted that NGAD’s present form may not be it’s last and that changes in leadership and budgets could impact how it continues to evolve as time goes on. Regardless, the picture that is emerging is of a cocktail of systems, many of which are unmanned—from extremely stealthy, B-21 like UCAVs to attritable drones—and the complex networks that will enable them, not of one single extremely high-cost program or aircraft type.

All told, it remains very much to be seen what combination of platforms and capabilities the Air Force will determine it needs to “dominate” future opponents in the air in the decades to come. But whatever it ends up looking like, some platinum-plated sixth-generation manned super fighter is very unlikely to be a part of it.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com