Northrop Grumman has reportedly held talks with Japanese officials about joining that country’s F-3 stealth fighter project. At the same time, Japan is also seeking offers from Boeing and BAE Systems as it searches for a foreign partner or partners to help speed the program along.

Reuters was first to reveal that Northrop Grumman was actively eyeing a spot in the Japanese program on July 6, 2018. Japan has been looking to develop its own fifth generation fighter, possibly with outside help, for more than a decade after the U.S. government blocked foreign sales of Lockheed Martin’s F-22 Raptor.

“Northrop is interested,” an unnamed source told Reuters. The Virginia-headquartered defense contractor has already held meetings with Japanese officials to outline the types of technology it could contribute to the F-3 program, but has not made a proposal based around a particular aircraft type.

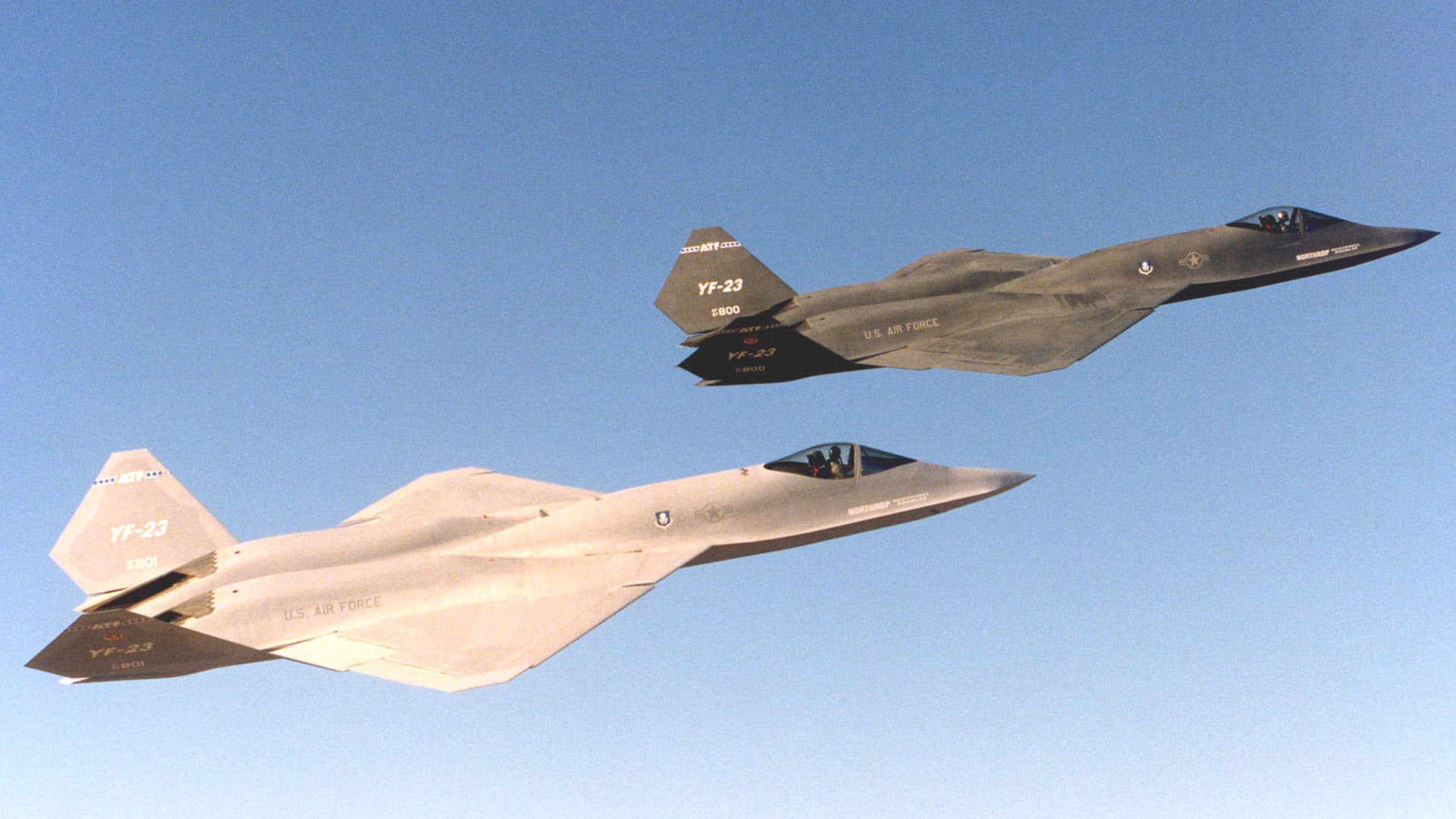

The last time the firm publicly developed a manned stealth fighter was in the 1980s when it pitted its YF-23 Black Widow, which built upon its previous experience in low observable designs in the XST, Tacit Blue, and B-2 programs, against the F-22 in the U.S. Air Force’s Advanced Tactical Fighter competition. Though the Raptor won that contract, the company has since gone on to develop a number of other manned and unmanned stealth aircraft designs, including the B-21 bomber, and is understood to be heavily involved in such work in the classified realm.

In addition, Northrop Grumman works as a sub-contractor to Lockheed Martin on the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program, building center fuselage sections for those jets. Earlier in July 2018, it began full-rate production of those components, expecting to build approximately 20 of them every month. Japan is also already a member of the F-35 project and Japanese firm Mitsubishi Heavy Industries is performing the final assembly of those jets in the country.

Still, any Northrop Grumman offer is likely to be immediately in steep competition with pitches from Lockheed Martin, which have already included a concept that reportedly includes design features from both the F-22 and the F-35. The Maryland-headquartered defense contractor also already has experience working with Japan on an earlier fourth generation fighter project, the F-2.

A Japanese partnership with either company could leverage existing technology to keep development costs – pegged at around $40 billion – as low as possible, as well as provide a vehicle for important technology transfer to domestic companies. So, though Japan is eager to court foreign partners for the F-3 program, it has made clear that domestic industrial cooperation will still be a core part of the effort.

According to Reuters, Japanese officials have made it clear that the final aircraft will include avionics and mission systems, a radar, communications gear, navigation equipment, and even engines from the country’s IHI Corporation conglomerate. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries will have to be involved in a significant portion of the physical production of the aircraft, too. In 2016, this company put its own stealth fighter demonstrator, the X-2, into the air for the first time.

And according to Reuters, the F-3 competition might not be limited to just Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman. Japan is still hoping to hear back from Boeing and British defense giant BAE systems.

Japanese officials have worked closely with Boeing in the past on domestic production of the F-15J Eagle. The company’s last attempt to build a manned fighter was with the X-32 stealth design, which notably lost out to what became the F-35.

In 2017, Japan and the United Kingdom also agreed to work together to develop a new, long-range air-to-air missile, derived from the advanced Meteor design, which will be an important weapon for any existing and future Japanese fighter jets. BAE Systems is part of MBDA, the European consortium that produces that Meteor, and will likely lead the shared effort on the British side.

But despite the flurry of activity, Japanese officials have yet to publicly outline a clear plan for when the development of the F-3 will even begin. Previous schedules had the project beginning right now, which our own Tyler Rogoway had previously noted was highly optimistic.

And the desire to bring in a foreign partner might actually lead to the need for additional time in the schedule to secure the appropriate export approvals and smooth over any political squabbles that could occur as a result. Japan has already experienced these issues in its failed attempts to purchase F-22s and the F-2 program. The latter aircraft is essentially a late model F-16 Viper, but is around three times more expensive per plane.

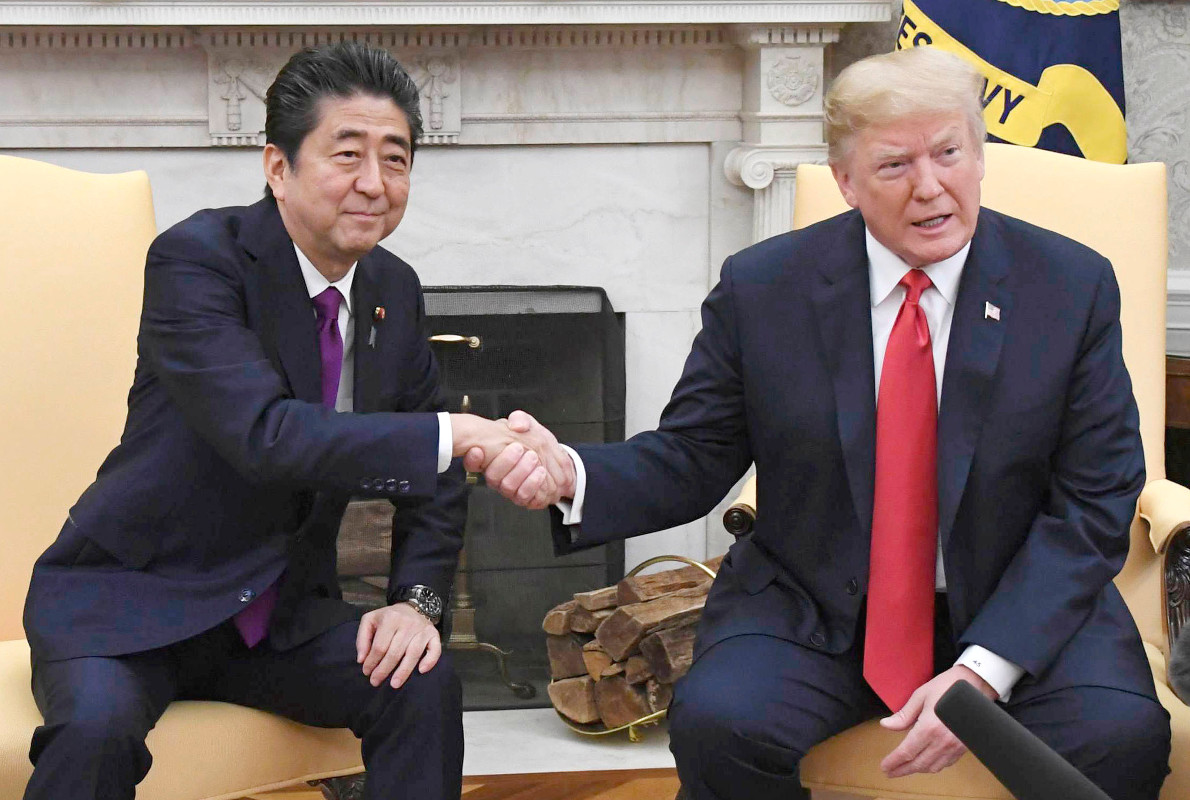

With no plans to export the plane, which the United States could easily have blocked to prevent competition with the Viper anyway, Japan had few avenues to try and drive those unit costs down. Any stealth fighter it builds that ends up full of American technology could face many of the same hurdles in securing any export sales, despite Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s close relationship with U.S. President Donald Trump.

Though Trump would likely be inclined to approve Abe’s deals with U.S. companies for Japan’s own use, the president has been especially eager to sell allies and partners American-made weapon systems. This could conflict with the Japanese government’s increasing efforts to become an international arms supplier in its own right, especially since any readily exportable F-3 could easily find itself in direct competition with the F-35. There is an entire tier of countries that could be very interested in an aircraft with Joint Strike Fighter DNA or similar capabilities, but without the need to join Lockheed Martin’s international program.

This might make an offer from BAE Systems, or another European competitor, attractive to Japan. France and Germany, for example, are working together on their own stealth fighter project, which will reportedly be “ITAR-free,” a reference to removing any components that would face export restrictions under the U.S. International Traffic in Arms Regulations rules.

Earlier in July 2018, Dirk Hoke, chief executive of the Airbus Defense & Space division working on this Future Combat Air Systems (FCAS) project, called for cooperation across Europe in the project. He argued that there was not enough room in the international fighter jet market for European aircraft companies to continue making competing designs.

“To look at the current scenario and to develop two or more solutions for the market is not sustainable,” he said. “It will bring [European industry] to the second league – we will not compete if we fragment the market further.”

Hoke also specifically said that BAE Systems could join the program at a later date. He also showed a video with a prospective tailless sixth generation fighter concept for the Franco-German program.

Separately, the United Kingdom and Sweden are reportedly in talks about partnering on a new fighter jet program. Japan could seek to leverage any of these cooperative European efforts for its own F-3.

The Japanese stealth fighter project will also be up against competing priorities within the countries own defense budget, though that might not be as much of an issue as it has been in the past. Abe’s government has sought to significantly increase Japan’s military spending and even amend the country’s pacifist constitution to allow for more flexibility in this regard.

It’s hard to see fifth generation fighters as ever being a low priority, either. Japan faces a standing threat of armed conflict with North Korea and the physical proximity of the two countries would quickly put Japanese jets in range of that country’s largely antiquated, but steadily improving and simply dense air defense network. This reality has already prompted the country to begin developing a number of air-launched, stand-off weapons to help its existing jets still hold North Korean targets at threat, and do so quickly, in any future crisis on the Korean Peninsula.

At the same time, Japan has been facing increasing challenges from both China and Russia over a number of territorial disputes. Japanese jets routinely scramble to intercept Chinese and Russian planes near the contested Senkaku and Kuril Islands chains.

To meet these and other security demands, Japan is still hopeful it can get an F-3 stealth fighter into service by the mid-2030s, according to Reuters. Given the historically time consuming and complex processes associated with fifth generation fighter jet projects, Japanese officials will have to settle on how they want to proceed soon if they want to meet that goal, even with any help from outside firms.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com