As part of the firestorm of rhetoric and provocative tit-for-tat military displays of force between the North Korea and the United States and its allies, which has included near constant flights of B-1 bombers and fighter escorts near North Korean borders, Pyongyang highest ranking diplomat now says the reclusive country has the right to shoot those bombers down—even when they are operating in international airspace.

DPRK foreign minister Ri Yong Ho said the following to reporters while in New York for the U.N. General Assembly:

“Since the United States declared war on our country, we will have every right to make countermeasures, including the right to shoot down United States strategic bombers even when they are not inside the airspace border of our country… In light of the declaration of war by Trump, all options will be on the operations table of the supreme leadership of the DPRK.”

Ri was referring to not only Donald Trump’s speech to the U.N. last Tuesday, but also to a tweet that the President sent out on Saturday:

Earlier on Saturday it was announced that B-1 bombers and their F-15C escorts had ventured north of the Demarkation Line that separates North Korea and South Korea for the first time in the “21st Century.” They did so in international airspace near North Korea’s eastern coastline.

Pentagon spokesperson Dana White said the following about the mission:

“This mission is a demonstration of U.S. resolve and a clear message that the president has many military options to defeat any threat… North Korea’s weapons program is a grave threat to the Asia-Pacific region and the entire international community. We are prepared to use the full range of military capabilities to defend the U.S. homeland and our allies.”

North Korea’s air defenses

North Korea’s air defenses aren’t by any means state of the art but they also aren’t as completely antiquated as some may think. If anything, they are dense and still pose a serious threat to U.S. and ROK air power. During a conflict, electronic warfare—specifically jamming—and a protracted suppression/destruction of enemy air defense (SEAD/DEAD) campaign will open up corridors into the country that non low-observable (stealthy) aircraft can operate in and out of. The first deep strikes of such a campaign would be executed by B-2 Spirit bombers and cruise missiles, as well as F-22s and F-35s if they are in the region, and they will be primarily aimed at neutering the Kim Regime’s nuclear weapons and missile arsenals, command and control capabilities, as well as critical air defense nodes.

With this in mind, the idea that a couple of these B-1s and a handful of F-15C escorts would penetrate deep into North Korean airspace to strike targets directly just isn’t that plausible. Even the F-35Bs stationed in Japan, which have recently flown an armed mission with the B-1Bs, may be able to penetrate deep into North Korean airspace, but they can only carry 1,000lb class weapons which are not capable of taking out hardened or large targets. Still, the B-1Bs pose a significant threat to unhardened and semi-hardened targets in North Korea anytime they are within a few hundred miles of the country as they would be used as cruise missile launch platforms during the opening stages of a war.

Additionally, just because these bombers and their escorts are flying outside North Korean airspace doesn’t mean they are safe from potential attack. North Korea has fielded a copy of China’s HQ-9 surface-to-air missile system—itself a copy of the Russian S-300 system—called the Pongae-5 and designated the KN-06. This indigenous SAM system gives North Korea a huge leap in anti-air capability over its Soviet era SA-2, SA-3, and SA-5 missiles. But even these older systems can be dangerous in a skilled operator’s hands.

The KN-06 can reach out many dozens of miles from North Korea’s borders. If the big bomber and their fighter escorts venture too close to North Korean shores, even while still well into international airspace, they could be confronted with this threat.

When it comes to North Korea’s largely antique air force, B-1 bombers—or any other aircraft for that matter—escorted by American fighters wouldn’t be the easiest of targets—quite the opposite in fact. North Korean jets, even their handful of dated MiG-29s, would have next to no chance of taking down an asset under fighter protection. But an armada of surveillance aircraft keeps tabs on North Korea on a daily basis. By and large these are unarmed, unprotected, lumbering flying machines. You can read all about them in this prior feature. So although the B-1s may be the most symbolic of targets, and they do pose a direct threat to North Korea, if Kim ordered the shoot down of an American aircraft, especially via air-to-air combat, there are plenty other targets—ones far more vulnerable—to choose from.

But the farcical possibility of North Korea launching an intercept on an asset protected by fighters aside, the thing is that even the B-1Bs’ escorts could do little in response to a missile launch if North Korea was able to fire one within range of the bombers. The aircraft have defensive countermeasures, the B-1B’s suite is quite elaborate when it works, but none of the aircraft seen on these show of force training missions could respond by firing a missile at the threatening SAM site itself. That may change following the foreign minister statement. Don’t be surprised if you see fully armed F-16CJs acting as counter-air and “wild weasel” escorts for the big bombers during their next mission.

The technological capabilities of North Korea’s anti-air arsenal aside, maybe the most worrisome aspect of North Korea’s threat against the bombers is that there is a precedent for such an engagement occurring—one that could have resulted in the nuclear bombardment of North Korea.

The doomed flight of DEEP SEA 129

Nearly 50 years ago, on April 15th, 1969, a U.S. Navy EC-121M Warning Star intelligence gathering aircraft—which was based on the legendary Lockheed Super Constellation—from Fleet Reconnaissance Squadron One (VQ-1), made its way from its NAS Atsugi in Japan to international airspace off North Korea’s eastern shore.

Its mission was considered low-risk in nature and included the gathering a whole range of signals and communications intelligence emanating from the reclusive country. The mission’s call sign was DEEP SEA 129.

The type of reconnaissance flight that DEEP SEA 129 was on that day was nothing really unique as under the program known as Peacetime Aerial Reconnaissance Program (PARP), code named Beggar Shadow, regular surveillance flights of North Korea common during the late 1960s. The Signals Intelligence gathering Warning Star and its 31 crew, of which nine were linguists and cryptologists, would head into the Sea of Japan and set up an orbit near North Korea’s border with Russia. The crew could come no closer than 50 miles from North Korean shores during the mission. After its intelligence gathering duties were finished with, the modified “Super Connie” would recover at Osan Air Base in South Korea.

On this mission, that recovery never happened.

Just after 12:30pm local time, nearly two hours after the DEEP SEA 129 had been on station, two MiG-21s launched from an airfield near Wonson, North Korea. 30 minutes later DEEP SEA 129 made a scheduled report but didn’t note anything out of the ordinary. US Army radar operators in South Korea had briefly lost track of the two MiG-21s around 1:22pm, but then reacquired them around 1:37pm—they were headed on a bee-line intercept course for DEEP SEA 129.

By 1:44pm DEEP SEA 129’s squadron, who monitored intelligence being actively passed across the national security network, had issued a “condition three” radio call to DEEP SEA 129’s crew, which told them they were possibly under attack. The crew immediately aborted the mission, turning the big piston powered aircraft towards South Korea.

Then the MiGs pounced. At 1:47pm the two fighters merged with the EC-121 and two minutes later the lumbering intelligence gathering aircraft dropped off radar. DEEP SEA 129 was defenseless as most intelligence gathering missions are by design, and continue to be so till this very day.

Everyone onboard the aircraft was killed in the engagement.

The response

At first it was thought that the crew may have survived and just dove the aircraft below radar coverage as a defensive maneuver. The pilots never radioed that they were under attack so interceptors were launched to give the aircraft cover as it returned to South Korea and also to create a higher alert posture near the DMZ. The EC-121 never popped back up on radar again. By around 2:45pm the incident was deemed a hostile shoot-down prompting emergency messages being wired to the National Command Authority. Search and rescue assets, with fighter cover, were deployed to search for DEEP SEA 129’s crew shortly after.

Within a handful of hours, North Korea quickly spun the shoot-down as a great accomplishment and claimed that the Warning Star had violated its airspace. But it remained unclear why the shoot-down was ordered. Nobody could really explain it from an external perspective, but there was no doubt that it was a massive escalation and an act of war.

In Washington, the Nixon Administration was struggling with how to respond. A total breakdown in command and control occurred following the incident. Information was scarce and even the location and status of American forces in the region were unclear. The process of simply reacting to the event based on quality information went on so long that a quick retaliation was not possible.

Nobody could tell if this was an isolated incident or one that came at the direction of the top echelons of North Korea’s military power-structure and just a sign of things to come.

While the White House was in disarray, fighters deployed to South Korea were loaded with tactical nuclear weapons and put on the highest alert, thankfully they were told to stand down hours later.

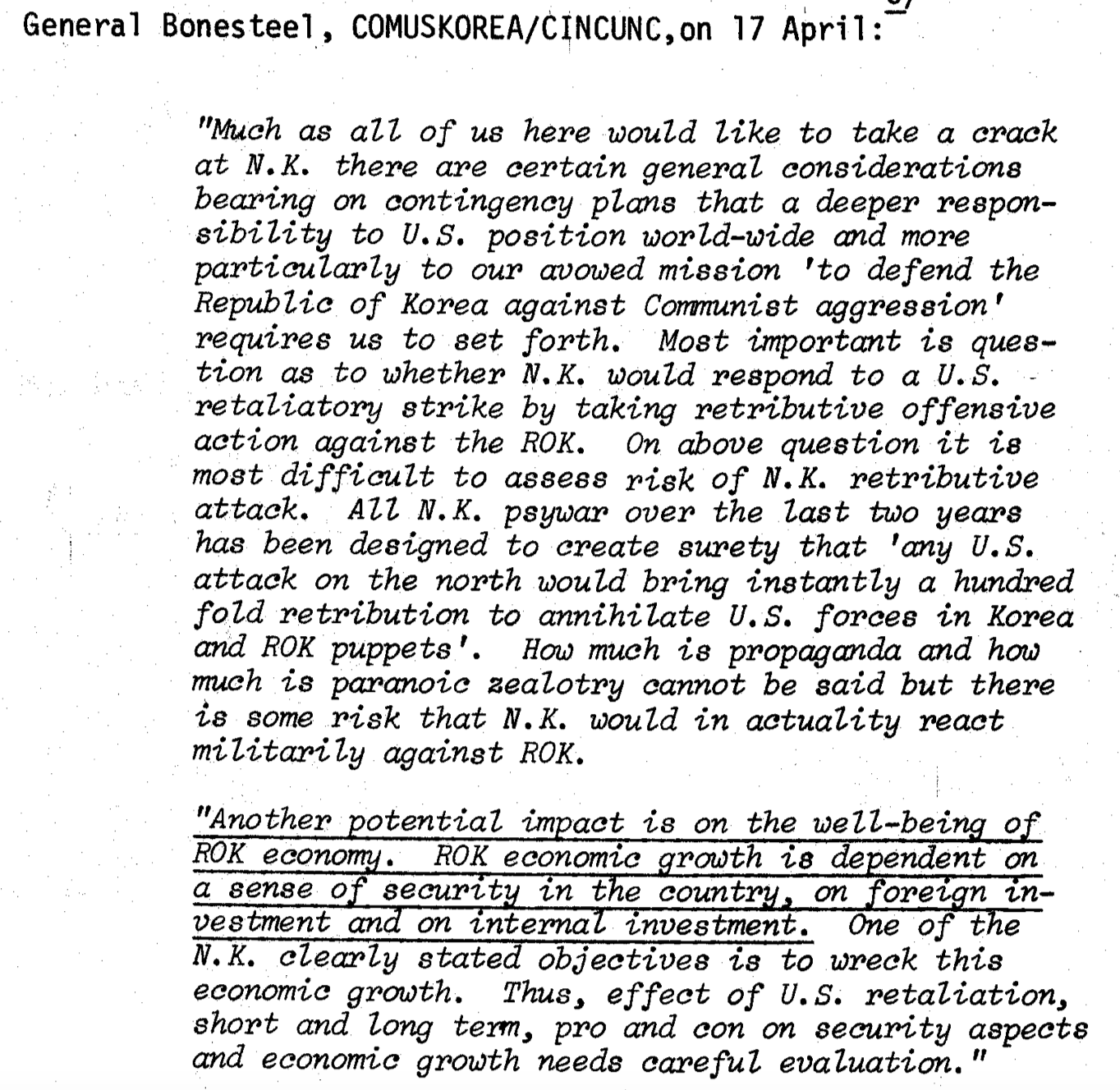

At first, the sentiment of some U.S. military commanders was to “clobber them” as a declassified after-action report describes. But just two days later, the reality of the consequences of such an operation began to settle in. Here is General Bonesteel’s memo penned just two days after the incident occurred:

As the days ticked by, North Korea didn’t change its overall military posture and they didn’t fly intercepts on other intelligence gathering assets that now either had fighter cover or had fighters waiting to launch in South Korea in a matter of minutes should they come under threat. Meanwhile, more air power was quietly moved into the region.

Nixon was presented with a revised menu of options not just for responding to the downing of DEEP SEA 129 but also as a contingency for future aggressive acts by the North Koreans. The Administration was clearly caught off guard by the shoot down and they didn’t want that to happen again. The nuclear option was briefed as part of this options list, but the truth is that during this period the use of tactical nuclear weapons in response to a North Korean act was always an option. Fighters sat on alert with B-61 nuclear bombs hung under them just for this purpose. Those weapons stayed in-theater till 1991.

Nixon mulled these options over and decided that he wanted the option to order the destruction of the airfield where the jets originated from. He could either order the strike as a retaliatory move for the shooting down of the EC-121 or he could reserve the ability to quickly do so should North Korea lash out again by going after an aerial asset. Plans were put into action to move naval assets, including four aircraft carriers, into the waters off the Korean Peninsula so that the counter-attack could occur on short notice. The naval flotilla amassed off the Korean Peninsula was dubbed Task Force 71 and included carriers Enterprise, Ticonderoga, Ranger, Hornet, and the battleship USS New Jersey among many other cruisers, destroyers and frigates. It was one of the largest military shows of force of the entire Cold War period.

Nixon never ordered the strike and North Korea didn’t make an attempt at another aircraft.

Then and now

In the end, the loss of DEEP SEA 129 and her crew of 31 was never avenged. In retrospect this might have avoided an all-out war on the Korean Peninsula while the U.S. was already buried deep in the conflict in Vietnam. Nearly 12,000 American servicemen died in Vietnam in 1969, and nearly 17,000 the year before. Another war, especially one as potentially bloody and costly as a conflict in Korea, would have been catastrophically unpopular back in the United States and even possibly unsustainable.

Fast forward to today, a time when tensions are at their peak, and you wonder what would happen if the North Koreans took another shot at a U.S. military aircraft operating near their borders? Nixon was widely praised for his restraint, although this was at the height of the Vietnam War when anti-military sentiment was prevalent. Would President Trump be equally celebrated for similar actions today?

Also, Trump and Nixon are very different people, and their responses to such a crisis would also likely be very different. The command and control architecture available to the Command in Chief today is also far superior to the rickety one that failed the Nixon Administration immediately following the shoot-down. A couple of days “cooling off” time really helped deescalate the situation even among America’s top commanders in the region.

Today, President Trump would have the military capacity to react nearly instantly—at least within a matter of hours following such a tragedy. This may be a technological blessing but could it also be a geopolitical curse?

One thing is certain, it’s amazing how little things seemed to have changed when it comes to North Korea in the nearly 50 years that separate the loss of DEEP SEA 129 and today. On the other hand North Korea is a nuclear power now and any counter strike could result in the use of these devastating weapons—a sobering and hard to quanitfy reality that Nixon and his generals didn’t have to face in 1969.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com