The U.K. Ministry of Defense has unveiled new plans for a new stealth fighter jet called Tempest at the biennial Farnborough Airshow. The announcement coincides with the release of a new Combat Air Strategy, which focuses heavily on sustaining and expanding the United Kingdom’s domestic defense industrial base and international cooperation in that sector, but there are already questions about the project’s viability given the country’s increasingly uncertain political and economic future.

Underscoring the emphasis on engagement with the private sector, U.K. Defense Secretary Gavin Williamson offered details about Tempest and the country’s new aerial warfare strategy in front of a full-size notional mockup of the jet at BAE’s booth at Farnborough on July 16, 2018. The U.K.-headquartered firm will lead “Team Tempest,” which also includes engine-maker Rolls-Royce, Italian defense contractor Leonardo, and the European missile consortium MBDA.

“We have been a world leader in the combat air sector for a century, with an enviable array of skills and technology, and this Strategy makes clear that we are determined to make sure it stays that way,” Williamson said. “British defense industry is a huge contributor to U.K. prosperity, creating thousands of jobs in a thriving advanced manufacturing sector, and generating a U.K. sovereign capability that is the best in the world.”

Though Tempest’s design isn’t anywhere close to firm, slides Team Tempest showed at the event described a number of increasingly common basic requirements for an advanced fighter jet design. Though described as a sixth-generation design, what BAE Systems and its partners have shown so far looks very much like what many countries are looking at for new fifth-generation types. The mockup and concept art show a stealthy, modified delta-wing planform with a pair of vertical small, outwardly-canted vertical stabilizers.

The aircraft will have two engines hidden away deep inside the airframe to help keep its radar and infrared signatures as low as possible. Rolls-Royce says they are working on an engine design that will leverage composite materials and advanced manufacturing processes to be lightweight, have better thermal management, and still keep costs low. The powerplants will have digital controls for more precise power management and to readily provide maintenance personnel with information about whether components need replacement and other aspects of the system’s “health.”

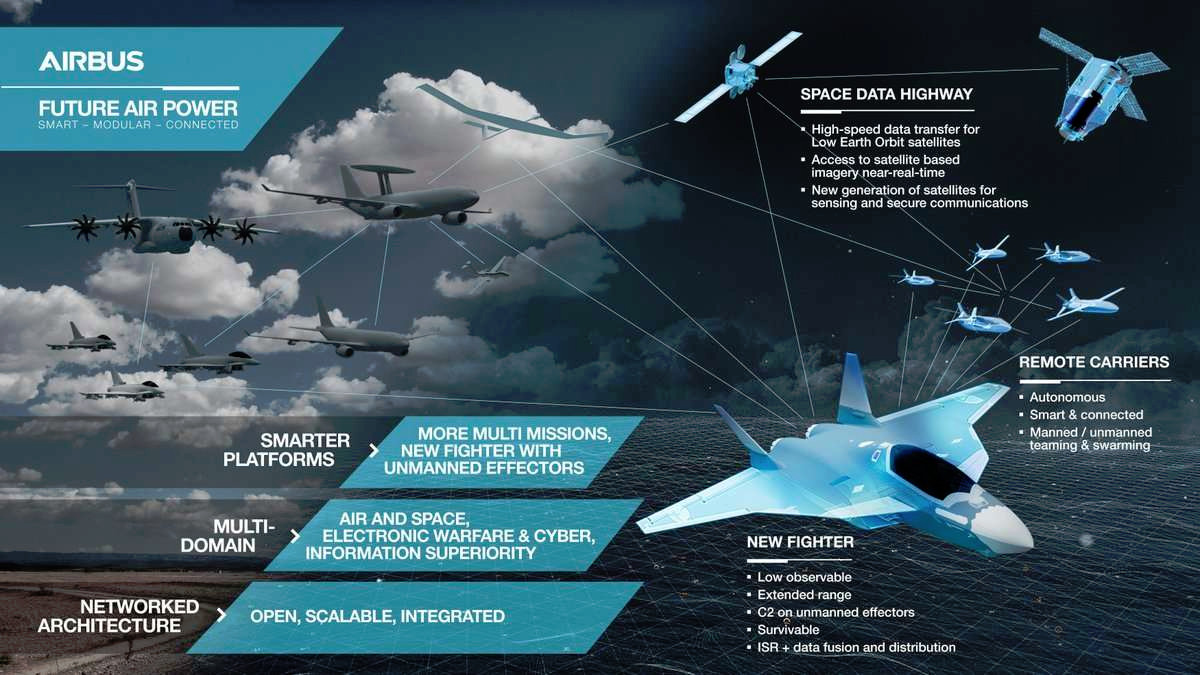

Tempest will have a wide array of sensors, including advanced radars and multi-spectral cameras, as well as unspecified data links and communications equipment. As with other advanced fighter jet designs, such as the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, the goal is to provide the pilot with as complete a picture of the battlespace as possible, allow the jet’s the to share that information with other friendly forces, and let the pilot pull additional data from other assets in the air, on the ground, and even potentially in space.

The United Kingdom is looking for a significant amount of modularity and reconfigurable components in the aircraft, too. The jets will have a modular payload bay, which could accommodate weapons – including offensive and defensive directed energy weapons – additional sensors, electronic warfare suites, or other systems to allow it to perform multiple roles. This could allow different aircraft in a single flight to carry only one type of system, with sensor-packing planes locating targets and feeding that information via their data links to others in the formation loaded with a maximum amount of weaponry.

Related plans to bake physical growth potential into the design seem harder to realize given the constraints of stealth aircraft designs. Despite what the presentation at Farnborough showed, it could be especially hard for BAE to bolt on additional equipment and maintain the aircraft’s low-observable characteristics.

The slides also described a need for “scalable autonomy,” which would imply an optionally manned capability, as well as a potentially artificial intelligence-driven set of flight and mission systems to reduce strain on the pilot and speed up their decision making processes. In addition, the goal is for a single manned Tempest to be able to issue orders to multiple autonomous pilotless versions, a concept commonly known as a “loyal wingman,” or otherwise control swarms of other, smaller drones.

The video below shows the BAE Taranis, as stealthy unmanned combat air vehicle the company has already been developing with an eye toward teaming with manned aircraft.

There appears to be a desire to push that level of autonomy into the ground support arena, as well. The briefing showed what appear to be notional robotic vehicles servicing the aircraft on the ground, which could, theoretically, help reduce the costs of sustaining the aircraft and mitigate the impact of a shrinking overall force, the latter of which being an especially pronounced concern for the relatively small United Kingdom. Making this work could be easier said than done, though, and might end up adding additional costs rather than saving any money.

The Tempest plan calls for at least one flying demonstrator aircraft by 2025 followed by deliveries of a production design beginning in 2035. By modern stealth fighter terms, it’s a somewhat aggressive schedule, which the overarching Combat Air Strategy seems to recognize is something of a theme. The document’s subtitle is “an ambition vision for the future.”

It’s not the first time the United Kingdom has attempted to develop its own advanced fighter jet, either. In the 1990s, the Royal Air Force launched the Future Offensive Air System (FOAS) program, which eventually led to the BAE Replica fighter jet concept.

The video below shows the mockup of the BAE Replica on display the company’s Warton Aerodrome.

That aircraft, which Tempest appears to borrow from in many ways, never flew and FOAS came to halt in 2005. The country decided instead to purchase the F-35.

In 2012, the United Kingdom and France embarked on what they called the Future Air Combat System (FCAS) project, which focused on developing stealthy unmanned combat air vehicles. Airbus has since used FCAS to describe a Franco-German stealth fighter program that also includes a number of similar requirements to the Tempest program, including supporting loyal wingman-style manned-unmanned teams.

Regardless, the U.K. government is clearly hoping to leverage these efforts for its own use to both speed up development and find ways to share burdens and otherwise lower costs. By their very nature, stealth fighter programs have proven to be very time-consuming and costly endeavors.

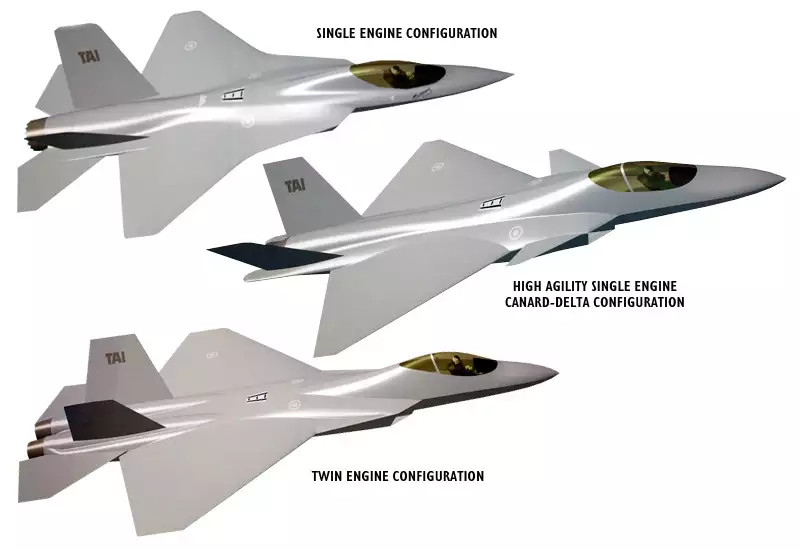

On top of that, despite the prominent Union Jack in the Team Tempest logo, it’s hard to deny that the program already has a distinctly pan-European flavor given the involvement of Leonardo and MDBA. Also, prior to the announcement, the Ministry of Defense had reportedly been in talks with Swedish officials about a shared stealth fighter effort. BAE Systems is already working together with Turkey’s TAI on its TFX program and could join Japan’s future stealth fighter project, as well.

“Government and industry will work together to achieve a more open and sustainable industrial base which invests in its own future, partners internationally and breaks the cycle of increasing cost and length of Combat Air development programs,” the document explained. “We will seek to balance military capability, international influence, economic and prosperity benefits.”

The immediate problem, of course, is whether the United Kingdom will be able to position itself as a viable partner, let alone leader in such a program given its present political and economic turmoil. This is almost entirely a result of plans to leave the European Union, also known as the British Exit or Brexit. The U.K. government is struggling to firm up its own negotiating position ahead of attempting to begin talks with E.U. officials on a deal to disentangle themselves from the organization.

If and when the United Kingdom succeeds in extricating itself from the regional bloc, it will immediately throw up barriers to direct industrial cooperation with European defense contractors. It will almost certainly make existing multi-national partnerships, such as MBDA and the Eurofighter consortium that produces the Typhoon fourth generation fighter jet, more complicated.

In many ways, Tempest appears to be a response to the Franco-German FCAS development, which itself was a response to concerns that Brexit would upend previous plans for a new European fighter jet program. However, Airbus itself has said that it could invite the United Kingdom to join the new FCAS program in the future and the Combat Air Strategy makes it very clear that the Ministry of Defense is interested in preserving those partnerships. There is a certain sense of desperation on both sides, though, who seem eager to downplay issues that are becoming increasingly unavoidable.

“For us, an eventual no deal with the E.U. would be a problem because we have a significant presence in the U.K.,” Alessandro Profumo, Leonardo’s CEO, said on July 16, 2018 in an interview after the Tempest announcement. “I hope that next month there will be the capability for the base of continuous cooperation in the defense areas.”

If Tempest doesn’t eventually merge with the European FCAS effort, the two programs could find themselves in competition, as well. Export sales would be an easy way to help try and lower the program’s costs, but, in this case, there might just not be enough potential buyers to make this a realistic possibility. Earlier in July 2018, Dirk Hoke, head of the Airbus Defense & Space division working on FCAS, argued that there simply wasn’t enough market space for more than one European stealth fighter project.

A bilateral or multilateral partnership, especially with partners outside Europe could still help spread the burden. However, countries such as Sweden and Japan are unlikely to buy any final product in large enough numbers to bring the United Kingdom’s share of the development costs or unit prices down substantially.

Economic uncertainty and austerity measures in the United Kingdom itself also mean that’s not entirely clear where the funding for a new generation fighter jet program will come from in the near term. The U.K. Ministry of Defense insists it is committed to also modernizing the Typhoon fleet and buying nearly 140 F-35s, among a host of other often competing priorities across its various branches.

Unfortunately, whether or not the United Kingdom will actually purchase the total planned fleet of F-35s is already questionable. The country only has 48 aircraft on order so far and there’s no guarantee this number will increase in the end, especially given the U.K. government’s recent cuts to defense spending.

In January 2018, the country put plans for additional defense budget cuts on hold until it had completed a still-ongoing spending review. It says it has already earmarked more than $2.5 billion for Tempest, but this is only a fraction of what would be necessary just for development of the plane, let alone significant purchases of actual planes.

There is also the matter of sustainment costs since the United Kingdom’s present plan is for the Tempest to serve alongside both Typhoon and the F-35 for at least a period once it begins entering service in 2035. If this is the case, the U.K. ministry of defense will be presented with the challenge of supporting two distinct stealth fighters, as well as a legacy design, at the same time. The experience with the Joint Strike Fighter program has already shown that keeping even modestly sized fleets of similarly advanced jets flying can be an especially expensive operation in its own right.

This only raises further questions about not just if, but why the United Kingdom would start work on another advanced fighter jet that is likely to offer similar capabilities to the F-35, but would immediately be in competition for the same pool of resources with that program. And the Joint Strike Fighter already has significant burden sharing among almost a dozen participating countries, including the United States, and the costs of upgrades are likely to end up spread across those partners.

With a demonstrator aircraft not even scheduled to take to the sky for more than six years, there is a distinct chance that the political and economic environment in the United Kingdom will have changed substantially before the Tempest project even gets going. Prime Minister Teresa May’s government has suffered a number of important resignations just in July 2018, including that of now former Foreign Minister Boris Johnson, and it is unclear how long she may last in that post.

With all this in mind, the Ministry of Defense will have to work hard if it wants to move Tempest ahead at all, let alone keep to its stated timetable. Otherwise, it’s very possible that the program could end up being a repeat of FOAS and the Replica.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com