Japan Marine United, or JMU, has launched the first example of a new subclass of guided missile destroyers for the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force, which will significantly boost the country’s ballistic missile defense capabilities, particularly with regards to North Korea. At the same time, though, the ship will enhance Japan’s ability to defend its own territorial claims and project naval power more broadly in East Asia and beyond.

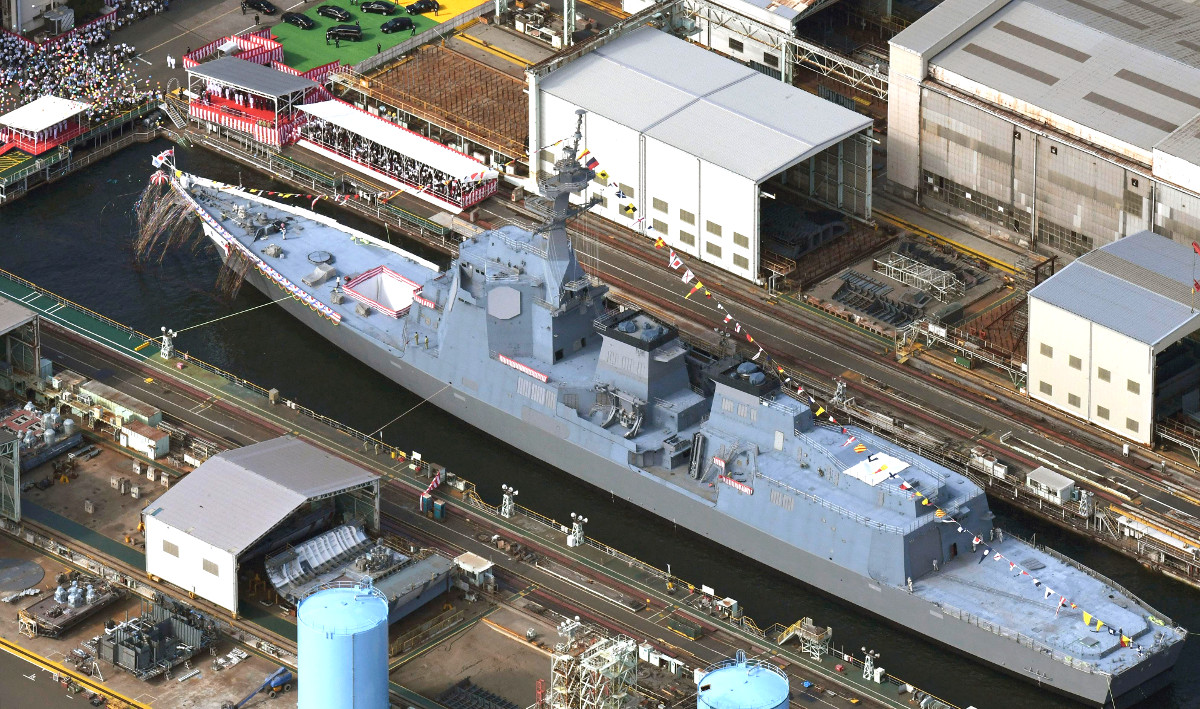

The future JS Maya slipped into the water during a ceremony, with Defense Minister Itsunori Onodera in attendance, at JMU’s shipyard at Isogo Ward in Yokohama, near the Japanese capital Tokyo, on July 30, 2018. The destroyer is the first of two so-called 27DD or 27DDG ships, which are subvariants of the Atago-class that is already in Japanese service. The Atago-class is itself an evolution of the Kongō-class, which are derivatives of the U.S. Navy’s Arleigh Burke-class, but feature a better radar horizon due to the superstructure radar placement being higher than it is on its American counterparts among other changes.

The Japanese Defense Ministry unveiled plans for the new subclass in August 2015. Maya is set to enter service in 2020, with her as yet unnamed sister slated for commissioning in 2021.

Though derived from the same hullform as the Atagos, the 27DDGs are bigger and heavier than their predecessors. The existing destroyers have a standard displacement of around 7,700 tons, while the new types will displace approximately 8,200 tons.

Perhaps the most notable feature of the 27DDG design is its improved combined diesel-electric and gas, or CODLAG, propulsion system. In this configuration, the diesel engines for propulsion and the generators for electrical power are combined into a single system, improving power management and efficiency and reducing maintenance requirements and operating costs.

This upgrade is a necessity in order to provide electricity to simultaneously propel the ship and supply power for the increasingly energy-hungry radars and other mission systems found on modern guided missile destroyers. When it comes to the 27DDGs, the most immediate demands are the ship’s advanced Aegis Baseline J7 combat system, which includes the AN/SPY-1D air search radar, as well as new Cooperative Engagement Capability (CEC) equipment.

The existing Atagos also use the Aegis Baseline J7 and AN/SPY-1D, but do not have the networking functions that the CEC offers. The CEC is part of the U.S. Navy’s broader Naval Integrated Fire Control-Counter Air (NIFC-CA) concept, which seeks to link all of that service’s ships, aircraft, and other assets together. Japan is also considering adding this network functionality to four E-2D Hawkeye airborne early warning and control aircraft it has on order from Northrop Grumman.

With the CEC systems, the 27DDGs, will be able to more rapidly share information with each other, as well as American ships during any potential crisis. This means the ships could receive high quality targeting data from other assets with the appropriate data links to cue their own surface-to-air missiles or anti-ballistic missile interceptors, even beyond the range of their onboard sensors. They could similarly provide that information to other Japanese or allied assets directly or by way of other platforms, such as the improved E-2Ds. Either way, this will be especially valuable in the ship’s primary air and missile defense role.

When it comes to the ship’s armament, when the 27DDGs enter service, they will likely have access to the same basic arsenal as the Atagos. The 96 Mk 41 verticle launch system cells can accommodate the RIM-66 Standard Missile-2 (SM-2) surface-to-air missiles and RIM-162 Evolved Sea Sparrow Missile (ESSM), as well as the RIM-161 Standard Missile-3 (SM-3) anti-ballistic missile interceptor. Each one of the cells can actually accept four quad-packed ESSMs, dramatically increasing the total number of weapons the ships can carry.

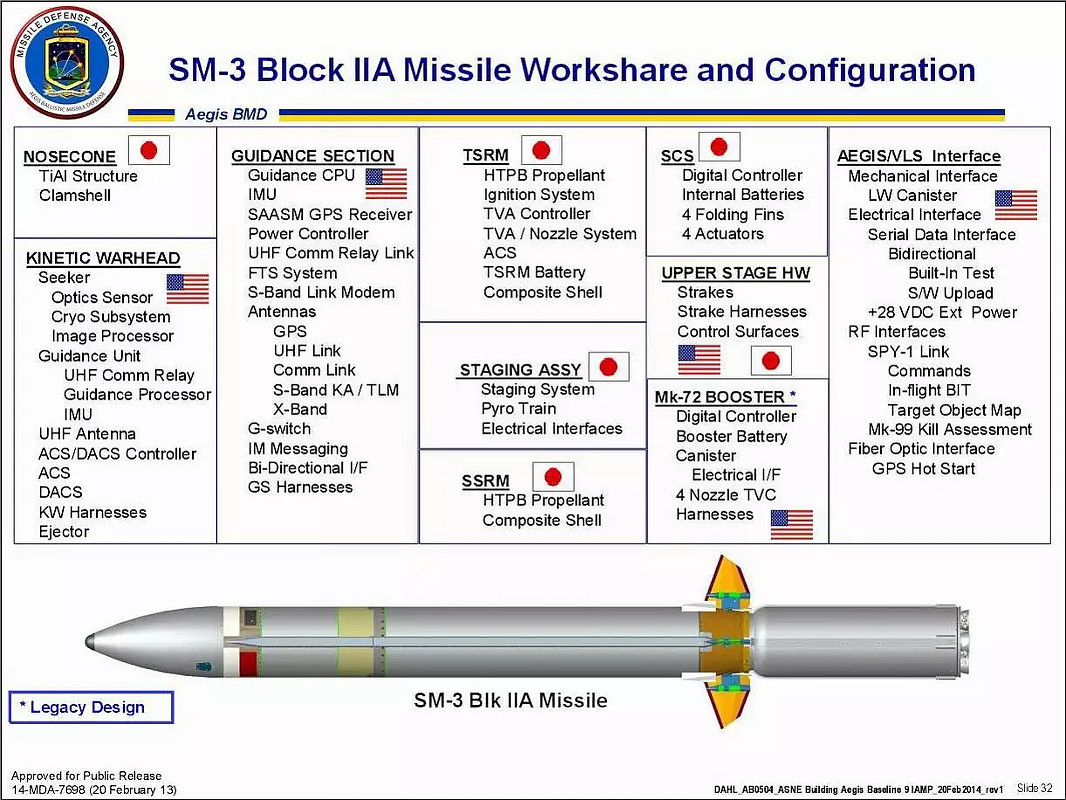

The new destroyers, along with their predecessors, will also eventually gain the ability to carry the still-in-development SM-3 Block II, which the United States and Japan are developing together. This is a much more capable anti-ballistic missile weapon than the existing SM-3s and, despite its name, is essentially a new design.

When the two 27DDGs arrive, together with the two Atagos and the four Kongōs, the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force will have a total of eight SM-3 Block II-capable Aegis-equipped ships. This will give it the ability to maintain a much more persistent maritime-based missile defense posture, which has become especially important in recent years given North Korea’s rapid development of increasingly capable medium-range, intermediate-range, and intercontinental ballistic missiles. The North Koreans have also shown a tendency to fire these weapons over the Japanese home islands, potentially putting Japanese citizens at risk, even during tests where an unarmed missile might fail and then fall into a populated area.

“In the past, the MSDF [Maritime Self-Defense Force] used to send Aegis destroyers [to monitor missile flights] only after it found some signs” that North Korea was preparing a launch, retired Japanese Vice Admiral Toshiyuki Ito, who served as commandant of the Kure Naval District, told The Japan Times. “But the North started repeatedly test-firing missiles without any advance signs. So the MSDF now needs to regularly deploy two Aegis destroyers.”

On July 30, 2018, the same day JMU launched the future Maya, Japan also announced it would be buying a pair of Lockheed Martin Long Range Discrimination Radars to go along with its two planned Aegis Ashore land-based ballistic missile defense sites. These facilities will also be networked together with ships offshore, including those the CEC data links and the first one could be operational by 2023, further expanding the country’s missile defense shield.

But the 27DDGs could signal the beginning of even more significant and far-reaching capabilities for the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force. For years now, the Japanese government has been instituting a steadily more active foreign policy involving its military and is coming closer all the time to amending the country’s pacificist constitution, which would allow it to deploy ships and other forces outside of missions that authorities can claim are self-defense related.

In addition to their extensive air and missile defense package, the ships will come with an updated AN/SPQ-9B surface search radar optimized for spotting and tracking low- and fast-flying targets, such as incoming anti-ship cruise missiles. Coupled with vertical launch cells full of quad-packed ESSMs, this could improve the ship’s defenses while operating off North Korea or while sailing into contested waters around Japan, such as the East China Sea, or further afield, such as the South China Sea.

Japanese and Chinese authorities dispute the ownership of certain islands in the former region and the government in Tokyo has increasingly joined other members of the international community in challenging Beijing’s claims in the latter area. In the South China Sea specifically, China recently installed new anti-aircraft and anti-ship defenses on some of its man-made outposts to further deny access to any potential opponent during a crisis.

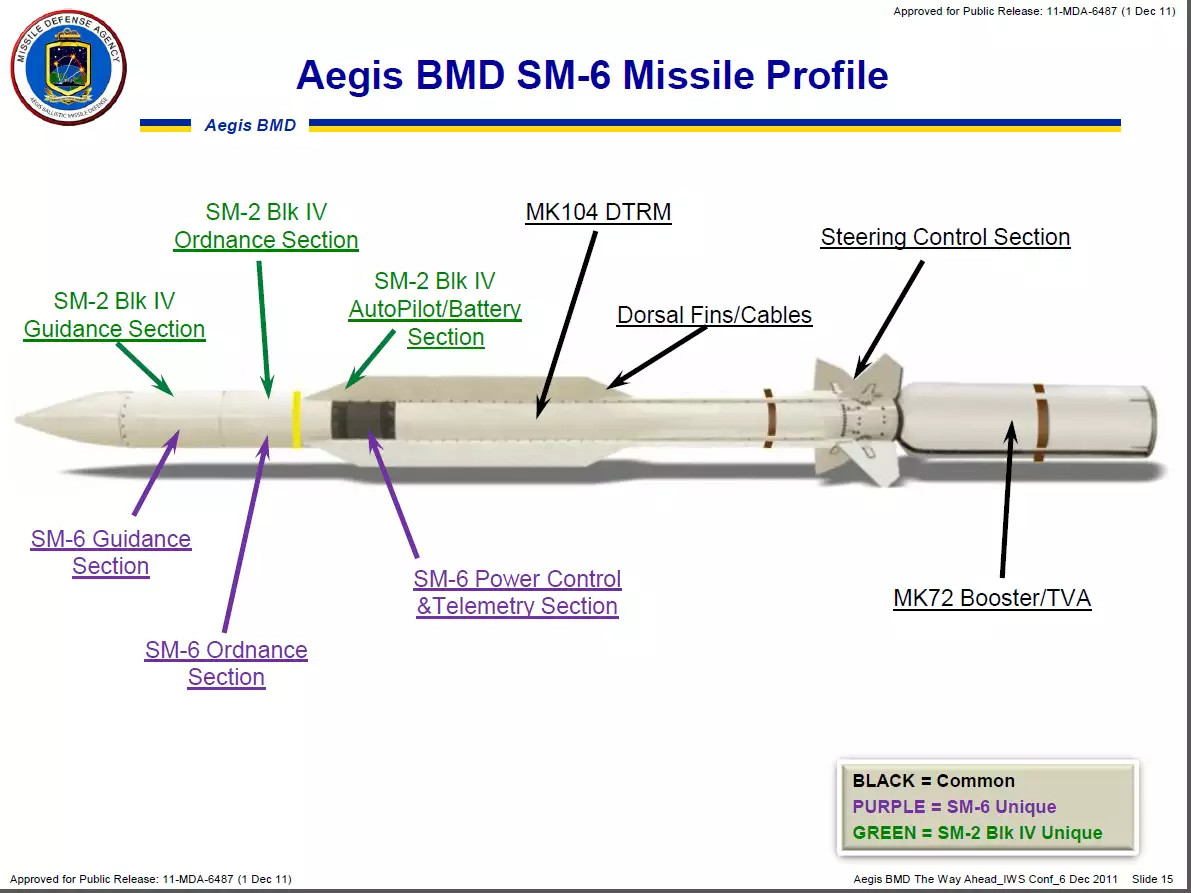

On top of that, Japan has plans to add the increasingly impressive RIM-174 Standard Missile-6 (SM-6) to the Maritime Self-Defense Force’s surface ships, including the 27DDGs, and possibly the Aegis Ashore sites. This weapon is fully networked and has the ability to receive targeting data from off-board sources, such as CEC/NIFC-CA equipped ships and aircraft.

This makes it a particularly capable surface-to-air missile against air-breathing targets, but it also has the ability to defeat certain kinds of ballistic missiles during the terminal stage of their flight. Manufacturer Raytheon has now even demonstrated its abilities secondary surface- and land-attack roles.

A mix of SM-2, SM-3, and SM-6 missiles could increase the flexibility of all of Japan’s Aegis destroyers significantly. This would increase their capabilities when acting independently or as part of a larger surface task force. The latter role could become especially important in the coming years as Japanese authorities look into modifying their Izumo-class “helicopter destroyers” into the short take-off vertical-landing aircraft carriers they’ve apparently always been at heart.

Any future Izumo carrier, loaded with F-35B Joint Strike Fighters and MV-22 Osprey tilt-rotors, could dramatically change Japan’s power projection capabilities, but would also need escorts. The 27DDGs, as well as the country’s other Aegis destroyers, would undoubtedly be important parts of any such strike groups.

In July 2018, Japan announced that it would send the Izumo-class ship Kaga to the Indian Ocean by way of the South China Sea as part of a regional tour. This is the second year in a row that the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force has done this, but it will only send the vessel with a single escort, hardly enough to protect it during an actual high-end conflict. The two ships are unlikely to even make much of a serious show of force given how rapidly China is expanding the size and capabilities of the People’s Liberation Army Navy. The Chinese are in the process of building a fleet of at least six new, advanced Type 055 destroyers of their own.

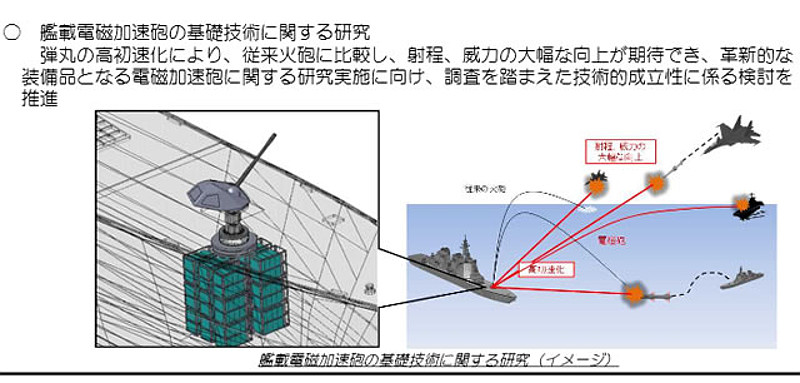

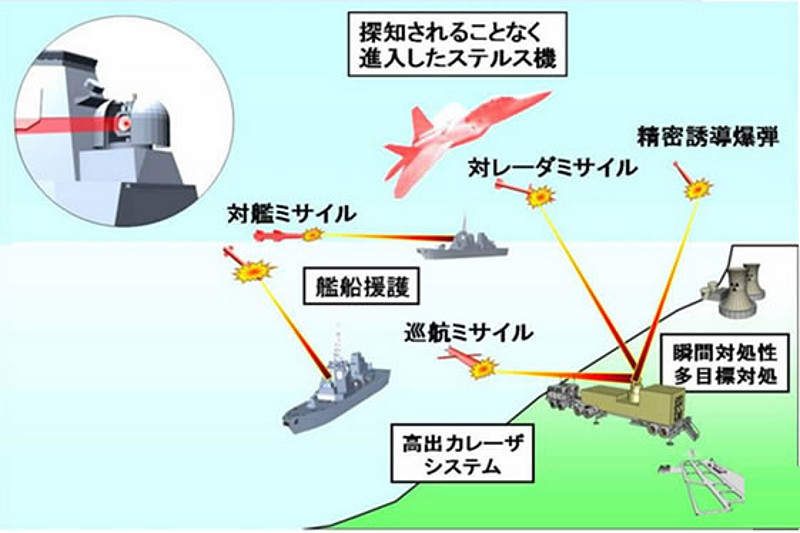

Looking even further into the future, the enlarged 27DDGs with their improved power-generating capabilities are also better suited to accommodating future upgraded systems. When the subclass first appeared in 2015, JMU went so far as to suggest that the ships might receive solid-state laser close-in defense systems or even an electromagnetic railgun in the future.

Of course, the U.S. Navy is exploring similar systems as possible additions to its own future surface ships, but has also increasingly come to the conclusion that its similarly sized Flight III Arleigh Burke-class ships simply do not have the physical space and power necessary for these upgrades. Japan may also hit the limits of the Atago–Maya hullform well before it gets around to installing any advanced weapons.

As it stands now, Japan does not even plan to purchase any additional 27DDG type ships beyond Maya and her sister-ship. If the Japanese government decides to further expand its military capabilities overall, though, the ships would offer an existing and known type that could add additional capability even if they turn out to have relatively limited room for further growth in the long term.

With an individual price tag of around $1.5 billion, the 27DDGs are already cheaper than late generation Flight II Arleigh Burkes and the design, or another derivative thereof, could offer a cost-effective path to expanding or modernizing the Japanese fleet. The youngest of the four Kongōs, the Chōkai has already been in service for 20 years.

Whatever the case, the future Maya and her sister ship will be important additions to the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force, especially when it comes to deterring North Korea, but also potentially in new roles as the size and scope of the country’s military continues to evolve.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com