Among the disclosures to emerge from the U.S. Department of Defense’s recent leak of sensitive materials, one of the most alarming — from the point of view of the Ukrainian Armed Forces — is a purported assessment of the precarious quantity of missiles available to Kyiv’s hard-pressed ground-based air defense systems.

While it’s important to note that the reliability of the contents of the hundreds of leaked classified Pentagon documents has been questioned, the critical need to replenish Ukrainian air defense missiles — as well as to replace Soviet-era systems with more advanced Western equipment — is something The War Zone has discussed from very soon after Russia launched its full-scale invasion.

Assuming this part of the document dump is a legitimate assessment, there could be massive consequences for Ukraine, with Russia potentially regaining the opportunity to execute fixed-wing air combat operations deep into Ukrainian airspace. This is in addition to targets in Ukraine becoming far more vulnerable to standoff missile and drone attacks. If anything else, it’s a reminder of just how precarious the delicate air-power balance is between the two countries and how important it is to rearm Ukraine for a longer fight.

Among the leaked materials, the most significant document in regard to stocks of air defense missiles appears to be one dated February 28, which provides an overview of Ukrainian missile usage rates and then projects when stocks of weapons for certain systems will be exhausted.

The document in question — or at least portions of it — was recently published by The New York Times.

The key claim included in this document is that Pentagon officials have assessed that Ukrainian air defenses assigned to protect troops on the front line will “be completely reduced” by May 23.

Were that to happen, Russian air power would be much less constrained in how it operates over the forward edge of the battlefield, with potentially disastrous consequences for Ukrainian troops on the ground. At the same time, by rolling back Ukrainian ground-based air defenses here, Russian aircraft would be better able to push further west into Ukraine, making it easier to target cities, and military installations — including airbases, as well as other key infrastructure, military and civilian — at least in some areas.

Eroded air defenses would allow Russia to be better able to overcome the limitations it now faces in terms of a dwindling supply of long-range standoff munitions. Not only are these generally expensive to produce but the strict sanctions now imposed on Russia make it much harder to replenish them. If the Russian Aerospace Forces were given more freedom of action by depleted Ukrainian air defenses, they could also make increasing use of shorter-range weapons.

Russian Aerospace Forces Su-35S multirole fighter jets deployed from the Eastern Military District to Belarus, from where many combat missions have been launched against Ukraine:

Ultimately, if the Pentagon’s supposed predictions about missile stocks were to come true, then the entire picture of the air war could begin to morph dramatically. Since failing to achieve air superiority at the start of the conflict, Russian tactical jets and helicopters have been very cautious in the face of stiff resistance from Ukrainian ground-based air defenses and fighters. Very often, Russian attack aircraft and helicopters have been forced to use unguided rockets fired from a very low level in the approximate direction of the target, with much-reduced accuracy as a result in hopes of hitting any targets near the front lines. Russian fighter jets, with far more capable sensors and weapons than their Ukrainian counterparts, have tended to operate outside Ukrainian airspace, firing missiles from very long range opportunistically.

According to the leaked documents, the Soviet-era S-300 and Buk accounted for 89 percent of Ukraine’s medium/long-range air defense capabilities, as of February 28. Depletion of missile stocks for the S-300 and the Buk would remove these systems as kinetic players in the overall defense of Ukraine, wherever they were stationed. The fact is that the wide variety of Western ground-based air defense systems now delivered or in the process of delivery to Ukraine are not available in anything near as significant numbers. The higher-end Western systems that have been delivered since the start of the war are being prioritized to cover major population centers, especially Kyiv, and likely little else.

As we reported at the beginning of the war, Ukraine started the conflict with an estimated 250 launchers of different types for its S-300P (SA-10 Grumble) long-range surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems, as well as a far smaller number of the related S-300V1 (SA-12 Gladiator/Giant) system.

No NATO militaries use the S-300V family of systems, ruling out the possibility of transferring additional exampels of these weapons to Ukraine, although the S-300P family does exist in NATO inventories and Kyiv has received at least some examples, including a complete S-300PMU battery (a more advanced version that those used by Ukraine) from Slovakia.

Bulgaria has one complete S-300PMU system, while Greece has 12 of the further improved S-300PMU-1 versions. These, or missiles from them, could potentially be supplied to Ukraine, too, although the reality is that stocks of missiles for the S-300 are always going to be limited and, at some point, will be exhausted.

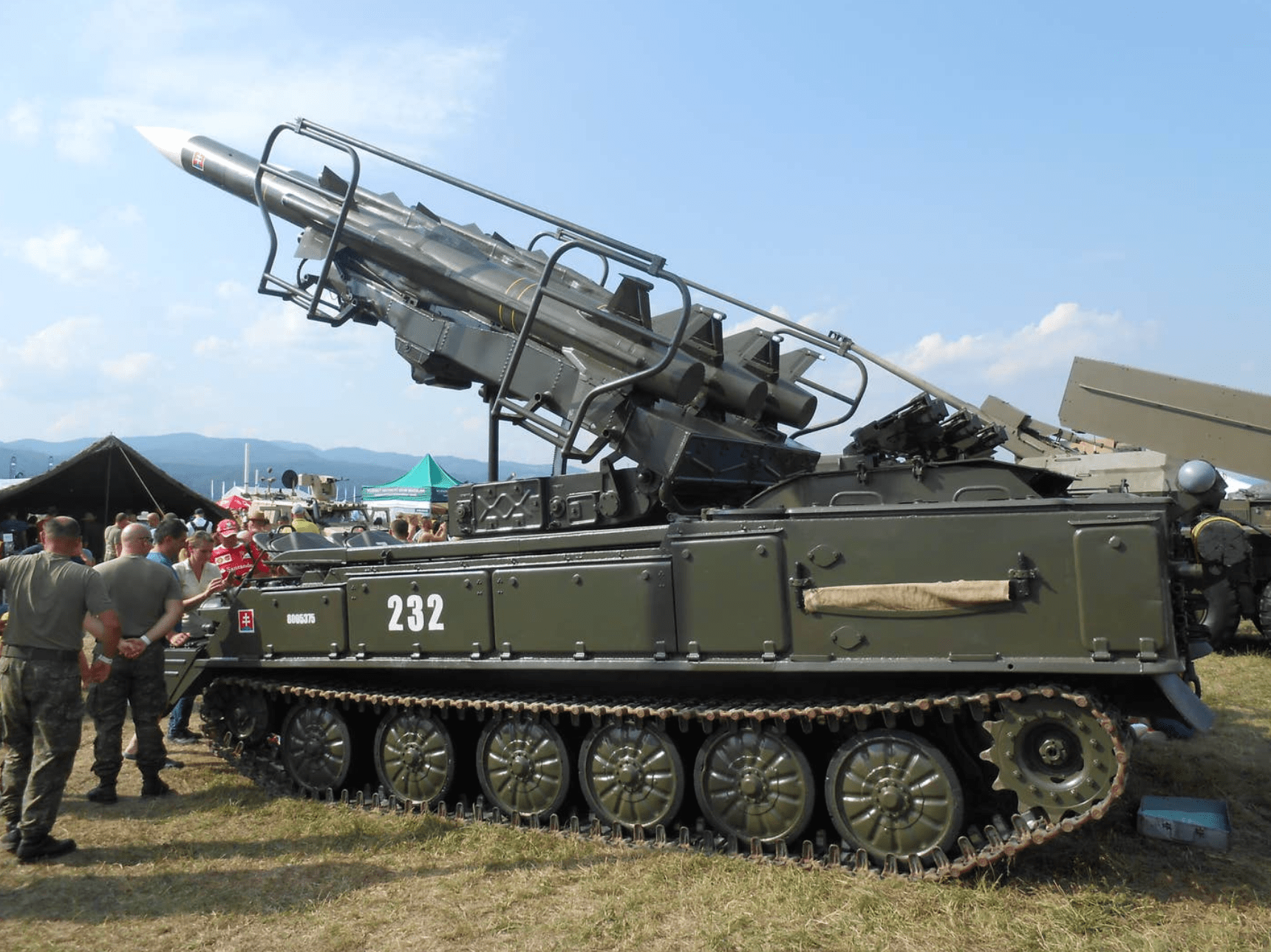

The situation as regards to the Buk mobile medium-range SAM system is even more problematic. Ukraine entered the war with a reported 72 examples of the Buk-M1 version available. There are no NATO operators of the Buk family. Within the alliance, only Finland previously operated the Buk, but all its remaining stocks are understood to have been scrapped.

Unable to provide additional Buk systems or the missiles made for them, the United States has approved the transfer of RIM-7 Sparrow missiles that will be integrated with the Ukrainian Buk systems. This is an innovative way of keeping the remaining Buk systems in the fight, but it’s unclear how long the process of adapting the Soviet-era Buk for these NATO-standard missiles might take or how effective it will end up being. You can read more about the initiative here.

A previous, Polish effort to integrate the Sparrow missile on the 2K12 Kub (the Buk’s predecessor), from around 2008:

Since our initial report on the state of Ukrainian ground-based air defense capabilities, there have been some significant transfers of systems of Western origin. Putting to one side man-portable air defense systems and very short-range air defense systems, Ukraine has begun to receive IRIS-T SLM systems from Germany, Crotale NG batteries from France, and MIM-23 HAWK systems from Spain and the United States. Spain has also supplied an Aspide 2000 battery, with similar SkyGuard Aspide/Spada systems being delivered by Italy.

Perhaps most importantly, Ukraine has begun to receive NASAMS batteries from the United States, with more scheduled to follow from Canada and Norway. As we have pointed out in the past, NASAMS has the considerable advantage of being able to draw upon the very deep reserves of missiles available from most NATO countries, primarily for air-to-air use. Already, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom have pledged to deliver AMRAAM missiles that will be used to arm Ukrainian NASAMS.

An official Ukrainian Air Force video showing the NASAMS in operation:

At the higher end of the SAM scale, Ukraine has recently received the first Patriot battery from Germany, with another to follow from the United States, together with two additional Patriot launchers from the Netherlands. These will provide enhanced long-range, high-altitude engagement capability that is currently only offered, to a lesser degree, by Ukraine’s S-300s, with their dwindling stocks of missiles. Importantly, the Patriot will also bring an anti-ballistic missile capability, something that is currently only provided by the small number of Ukrainian S-300V1 systems, and even those don’t come anywhere close to the Patriot in this regard. Providing somewhat similar capabilities to the Patriot is the SAMP/T, a joint Franco-Italian SAM system, one battery of which is also headed to Ukraine.

The advanced Patriot system promises to be a very welcome addition to Kyiv’s armory, although it’s somewhat less mobile than the S-300P series — and considerably less mobile than the S-300V1 — and will be a prime target for Russian suppression/destruction of enemy air defenses (SEAD/DEAD) missions.

Meanwhile, there have also been efforts to supply Ukraine with Soviet-era air defense equipment from NATO stocks although, as previously noted, the supplies of these systems are rather more limited. Poland, which has been a staunch backer of Ukraine, has provided examples of the 9K33 Osa (SA-8 Gecko) mobile short-range air defense system (SHORADS) as well as the S-125 (SA-3 Goa) medium-altitude SAM system.

The S-125 was understood to have been withdrawn from Ukrainian service sometime before the full-scale Russian invasion, although, more recently, there have been signs of reactivation — or perhaps evidence that the system was never entirely retired from service. Another Soviet-era system not known to have been in Ukrainian use prior to the invasion is the medium-range 2K12 Kub (SA-6 Guideline) SAM system, which Slovakia recently agreed to deliver to Kyiv in the form of the upgraded 2K12M2 Kub-M2.

Clearly, the influx of ground-based air defense systems of different types and from various sources reflects the very obvious requirement to sustain and reinforce Ukraine’s capabilities in this regard, to continue to apply pressure on Russian air operations.

Regardless, the possibility that the missiles fired by Ukrainian S-300 and Buk systems could be exhausted, sooner rather than later, is highly troubling, but it’s also a fact that new, NATO-supplied ground-based air defense systems are still being delivered and the most capable of these have not yet been brought online. Once they are operational, they will likely have a significant impact on Russian air planning.

Still, beyond the potential of weapons like the Patriot to become a major factor in the air war, it’s no secret that numbers are just as important as capability. Indeed, it’s notable that Ukraine has spent a disproportionate effort in countering Russian ‘kamikaze drones,’ like the Iranian-designed Shahed series, which have, in the past, at least, been launched in significant numbers, placing a considerable burden on Ukrainian air defenses. Added to this are the repeated barrages of cruise missile attacks launched from different Russian platforms and ranging from stealthy air-launched subsonic weapons, to ship-launched cruise missiles. Russia has also made use of Mach-4-capable Kh-22 anti-ship missiles used in a land-attack role, defense against which has apparently proven next to impossible.

As Yurii Ihnat, a spokesman for Ukraine’s Air Force Command, told The New York Times, “The question is numbers. To fully replace [existing SAM systems], we need many systems, and I won’t tell you how many.”

As it stands, the tables in the air war are delicately balanced. After receiving a fairly severe mauling at the start of the conflict, the Russian Aerospace Forces has never fully taken the initiative, with Ukrainian ground-based air defenses and fighter jets using bold and innovative tactics to ensure the skies over the country remain dangerous to the invaders.

Without a doubt, however, the Russian Aerospace Forces loom over the Ukrainian Air Force in terms of size as well as possessing key technological advances, including in the realm of sensors and weapons. One of the recently leaked Pentagon documents assesses that Ukraine has 85 fighter jets available, compared to 485 Russian fighter jets deployed in the Ukrainian theater.

“We do know that Russia has a substantial number of aircraft in its inventory and a lot of capability left,” U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III warned back on February 14, during a visit to Brussels. “We need to do everything that we can to get Ukraine as much air defense capability as we possibly can.”

So far, Ukraine has managed to do more with less and deny Russia air superiority. Exactly how accurate the assessments found in the leaked Pentagon documents turn out to be, they should serve as a warning call to Ukraine’s allies. If it’s to continue to keep Russian airpower at bay, the Ukrainian Armed Forces need a continuous flow of ground-based air defense systems (among other key weapons).

Should the effort to bolster Ukraine’s ground-based air defenses fail, the results could be disastrous. In the worst-case scenario, Russian airpower could have another shot at gaining air superiority — or at least operating deep over certain parts of Ukraine for brief periods of time.

The influx of Western air defense systems means that major population centers will still likely have robust coverage, but this could also be put at further risk by emboldened Russian Aerospace Forces. After all, if able to effectively run tactical fixed-wing operations over large swathes of the country, this would include suppression and destruction of enemy air defenses (SEAD/DEAD) missions, with the express purpose of targeting Ukrainian ground-based air defense systems. Russia can do this with standoff weapons and the most valuable of systems like Patriot and NASAMS would be top targets.

For general strike operations, as we have mentioned, Russia would be far less reliant on air-launched standoff munitions, allowing cheaper and more plentiful shorter-range and unguided weaponry to be brought to bear on certain targets. With the limited gains made by Russia in the conflict so far, the chance to secure something like air superiority over portions of Ukraine could potentially change the course of the war.

Ukrainian fighters, still very limited in number even after being bolstered a bit by allies, would also be put at far greater risk. Russia has superior air-to-air capabilities and Russian fighters pushing deeper into Ukraine could force engagements that Ukraine’s fighter force is not likely to win, at least on paper. Even on the ground, Ukraine’s fighter force would become more vulnerable.

Beyond that, it should be remembered that the bleak picture painted by the leaked Pentagon documents refers specifically to the S-300 and Buk — and as such concerns the upper-altitude blocks within a layered ground-based air defense system. The situation in regards to SHORADS is likely much less concerning, with significant numbers of these systems still in place, and more arriving, backed up by highly mobile very short-range air defense systems, including man-portable air defense systems (MANPADS).

This means that while low-level operations would still be very contested along the front, higher-level ones could open up to Russian forces. As such, a mix of low-level and high-level tactics could be employed, including crossing over the lines at high-altitude and dropping to much lower altitudes while deeper inside Ukrainian-controlled territory to avoid high-altitude systems still clustered around a handful of population centers.

Russia would still have to commit to such a strategy and its fixed-wing tactical assets would still be put at high risk even in a degraded air defense environment, especially early on. But if Putin and his generals see an opening, the possibility of bringing fixed-wing air combat power to bear deep into Ukraine, and working to degrade its defenses further in doing so, maybe just too sweet an apple not to pluck off the tree. This is especially true considering the state of Russia’s ‘Special Military Operation’ and the need for some major wins.

Ukraine’s finite missile stocks available to the S-300 and Buk systems were never in doubt and these weapons, which have played a key role so far in the conflict, require replacement by systems that offer at least as much capability, if not more. It’s quite remarkable these Soviet-era stockpiles have lasted as long as they have. But just as importantly, the systems that replace them need substantial quantities of missile reloads, whether drawn from active production lines or from existing NATO stocks.

Where exactly these systems and the inventories of missiles needed to make long-term use of them will materialize from is another question altogether.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com