The Army’s potentially revolutionary integrated air defense networking and command and control system carries the somewhat vague moniker Integrated Battle Command System, or IBCS. It aims to connect disparate sensors and missiles, but also potentially cannons, lasers, electronic warfare capabilities, and more (commonly referred to as effectors), across a battlespace to counter enemy aircraft and missiles. IBCS has had a long and somewhat tortured development, but now, after a highly successful test last August, it seems to be coming into its own and could finally move from a research and development effort to a production program in the near future. Its operational deployment would drastically increase America’s ability to defend its forces from all types of aerial attacks, and it would provide a fertile open-architecture command and control and networking environment that can incorporate fast upgrades and future additions of more sensors and effectors that are all tied together in a seamless and highly-automated fashion.

We hear a lot about networks, computer systems that are weapons onto themselves, data-links, and sensor fusion these days. Often the real capabilities a system offers, or doesn’t, gets lost in an avalanche of acronyms and jargon. It all sounds more like magic and a good PowerPoint presentation than reality. Such systems are far harder to comprehend and even define than say a new fighter jet program, early warning satellite, or armored vehicle. This does a major disservice to something like the IBCS that stands to dramatically change the way the Army, and the joint force it is so deeply connected to, fights. As such, we wanted to cut through the muck and get to the essence of this system, including getting a clear view of its capabilities now and what it could be capable of in the future.

With this goal in mind, we went in-depth with Northrop Grumman’s Kenn Todorov, Vice President and General Manager, Combat Systems and Mission Readiness. The resulting conversation isn’t just enlightening in regards to IBCS, but also in terms of better understanding the future of highly networked and automated warfighting.

Here is that interview:

Kenn: In our portfolio and my portfolio here with the company, we have the Integrated Battle Command System [IBCS], and I always… I hesitate when I say Integrated Battle Command System because until very recently, the Army was calling it the Integrated Air and Missile Defense, that was the I, Battle Command System, but now it’s shortened much… It’s easier to say, but for me, it’s not because for years I’ve been saying IAMD Battle Command System, but… IBCS is of course the Army’s program of record.

They are our customer, and we’re very much in partnership and cooperation with them. We have been developing the system for nearly a decade now, and it really stems, Tyler, as I think you know, from the Gulf War with numerous fratricides in the battlespace, in the IAMD arena, particularly when the battlespace was just so complex that the warfighter was having difficulty weeding through important information and making decisions in real-time that led to some very unfortunate events.

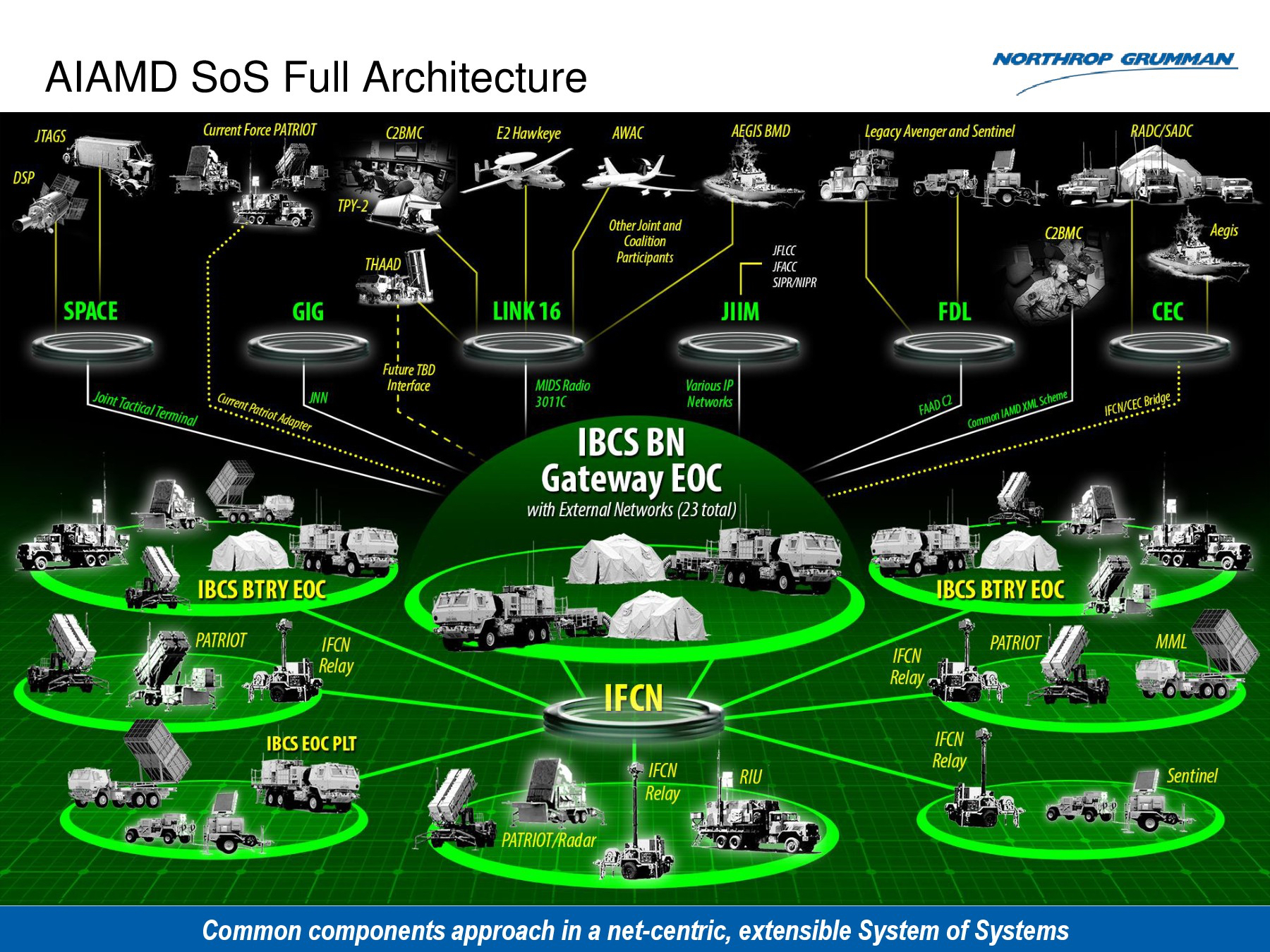

Since those days, we have been, frankly, hard at work, and particularly in the last decade, on a modular, open-architected system that… employs a net-centric integrated fire control network that enables the acquisition, identification, and engagement of air and missile threats of all kinds. And so IBCS is an exciting system, I think we’re very proud to work with our customer in the United States Army as they develop it, as they near a Milestone C decision this fall and enter into full production…

Tyler: What capabilities does IBCS have today? Can you run down the list of what it can do and then juxtapose that as far as what in the future you’re hoping to make it capable of? We hear the acronyms and whatnot, and I think it’s kind of like, “Okay, yeah, I get it, you get a common picture. And it says it shoots down multiple things, provides multiple tracks, uses data links,” I think a lot of people’s eyes just glaze over. So, if you can give us the best top-down look at the system and how it works and what it can do, and then what you want it to in the future, that would be really helpful.

Kenn: Great. And I understand the question and I also understand the tendency for people like me particularly to talk about it in this high-tech kind of way, but at its core, I think what IBCS does is simplify the battlespace for the warfighter. When you look at the complexity of that space and how it’s grown and the threat has grown in quantities and qualities, but also diversities, and now you’ve got all ranges of threats, literally from the surface up into the exo-atmosphere. IBCS as a system can weed through all that information, and then, based on its modular, open system architecture approach, it can really adapt feeds and data from any of the sensors that might be out there to include airborne sensors like the F-35, but radars, airborne sensors, sensors that are maybe maritime-based, and it takes that into a single integrated air picture. But then the really unique thing about the system is its fire control capabilities in that it’s able to then recommend—there’s always a woman or a man in the loop—but recommend to the warfighter which effector [such as a missile, gun system, laser, microwave system, even electronic warfare] might be best used against a particular threat. Whereas, before, you had sort of stoved-piped systems that were developed in concert with each other, but frankly, without much consideration to linking with disparate systems in the battlespace.

IBCS can now, I’m gonna say it’s sensor and shooter agnostic in that it doesn’t care where the information might come from, it just wants to take that, fuse it with the rest of the data that it’s seeing, and create a really sharper picture for the warfighter to weed through some of those difficult circumstances and then make a recommendation on which effector might be best served to go after a particular threat.

So, if I can give you an example of that, which I think was really remarkable. In the most recent limited user test, which we concluded… I say we concluded, to be clear, it’s the Army’s test, we were participating in it as their prime contractor. But on August the 20th and I’d refer you to the Army for specific details, but there was a cruise missile surrogate airborne and a theater ballistic missile airborne, and IBCS was doing its thing through a myriad of challenges presented to it, like electronic warfare, electronic attack to try to spoof it.

It was able to ignore those attacks and pass tracks from different sensors to each other, and then it was able to recommend a specific Patriot battery to shoot a PAC-3 at the threat, and, interestingly, it didn’t leave the launcher… There was a problem with the effector that was going after the threat, and what IBCS did was say, “Okay, got it. There’s a problem there. I’m now gonna recommend this next best shooter to take the shot,” which it did.

The warfighter acknowledged and took that shot and they splashed the target beautifully.

So, in that situation, you had the system that was helping the warfighter think through the problem, seeing through a myriad of challenges like EW [electronic warfare] and low mass terrain and the cruise missile surrogate flying low while the theater ballistic missile was flying high. Sending solutions to the warfighter on which effector should take the shot once the weapons release authority was granted…

Then when there was a problem, which, by the way, wasn’t part of the test, it just happened naturally in the system, the IBCS system recognized that and actually selected a different effector to take the shot, which it did and made the hit.

So, maybe a long answer to your question, but that’s trying to simplify really what the goodness of a system like IBCS does, and was really proven, I think, in the Army’s test in the desert…

For the future, as I mentioned, IBCS is clearly the Army’s program of record, and that’s a priority for us as a company. But the architectural framework that IBCS is built on this modular, open, software-defined, hardware-enabled framework, that can be applied in a number of different ways. It can be applied to… the Air Force’s ABMS construct, or… I know you’ve heard and written a lot about JBMS… I said JBMS, I meant the JADC2, the Joint All Domain Command and Control, where you’re having to now take what IBCS does and then sort of take that to a cross-domain kind of solution from all domains, to include space and cyber.

So, I think the future of a program like this, and the thing we’re thinking very keenly on, how do we apply the architectural framework or the technology that IBCS is built upon. Ignore IBCS because that’s the Army’s program of record, but what the system can do might be applicable to others in the department, to other services, to even our friends and allied partners across the world. As you know, I think Poland is already on contract for IBCS. Other countries as well have expressed interest in it. So, I think, as this capability continues to mature, it’ll be the command and control system of choice, at least in the integrated air missile defense fight and perhaps in other areas as well.

And the last thing, Tyler, I’ll say… I think the thing I would conclude this with is the ever-changing nature of the threat is such that you need this open architecture system to stay relevant to the future, because if you build things in a stovepipe way and then new threats or new capabilities come along, be they hypersonic, be they, you name them, new UAS systems that are stealthy, etcetera, etcetera, you can imagine these different kinds of threats that show up. Now, if your system is closed and it’s never quite as good as it is the day it leaves the manufacturer’s floor and gets out there, and now there’s a new requirement for it, with IBCS or a system like it, you can continue to add capability through this modular openness. You can continue to add sensors every year or as new capabilities come around, new effectors to deal with those new threats. So, I think when we talk about the future, a system like this is very exciting because it’s extensible to that future.

Tyler: When you talk about this being adaptable and open architecture, so there are quite a few different systems that have a similar, let’s just say brochure, but are not necessarily for the same thing. They’re dealing with different threat profiles, different domains of warfare, but they do similar sensor fusion, with some sort of AI built-in or at least high automation to help the warfighter actually make decisions or approve decisions. Do you see IBCS as being something that could be the system that links all systems or do you see it as one system that could plug into a system that links all systems?

Kenn: Yeah, that’s a great question… I want to be careful again to distinguish the Army’s program, IBCS, with where maybe your question is going with this. So, it’s not for me to say whether or not the Army is offering this up to other services or if other services are interested in the Army’s program per se. But again, going back to the capabilities resident in the program itself, which can be applied in a number of different ways. I think the potential is there. I don’t see this as the end-all-be-all network for the end of time, but rather as a network that has acquisition, identification, and most importantly, fire control enabled in it that can plug into others for the basis of an architecture or for extending the architecture or for a different part of the domain space. For instance, shorter-range integrated air-missile defense. So, I’m not trying to say that this capability can be a panacea for all of the JADC2 desires out there, but rather, it certainly can, this architecture can be built upon, and I think it’s worthy of exploration about how far it can go.

Tyler: On the fire control side and actually on the identification and tracking side, too… There’s obviously ballistic missile defense, hypersonics are now gonna be the next thing, trying to counter that, which is a huge bag of snakes. And then there are the various traditional air-breathing threats that you’re dealing with today. What about the very low-end? What about the quadcopter or small UAS swarm and the very low-end side of the Army’s air defense puzzle, which, honestly, is looking to be the most troublesome in the years to come. Does this system have the ability to deal with that voluminous lower-end threat as well as the higher-end threats?

Kenn: The short answer is yes, on the lower-end threats. In fact, it’s very much… I think as we listen to the customer and to the department talk about these challenges, the very challenges you kind of mentioned, we are doing a lot of work here at Northrop Grumman with regard to counter-UAS and how do we then take a kinetic control system like an IBCS, or one like it, and work in conjunction with some of the other kinetic and even some non-kinetic capabilities to deal with the problems that you just succinctly laid out. These quadcopters, these swarms of UASs… Our thinking is that this system is very capable, then, as I mentioned, any effector really, you can integrate with it. But we’re actually taking it a step further and some very specific capabilities we have resident within the company, and in the course of the next 18 months, we are going to be demonstrating some of those on ranges around the country.

And we’ve got some… I can’t get into… I don’t think too many specifics today, but certainly something I can follow up with you on. But actually taking a system like an IBCS and linking it with a 30-millimeter cannon or with a high powered microwave capability or with some other kind of a missile capability and demonstrating the very thing that you’re talking about, sort of the low-end tactical fight.

The other one that’s very much in the forefront of our mind is the Army’s DE M-SHORAD [Directed Energy Mobile Short-Range Air Defense System], which we’re involved in right now is to put a 50-kilowatt laser on a Stryker vehicle, and that program is in development. And, again, we’re one of two companies that I think are vying for that opportunity.

We’re thinking beyond the laser platform itself, but rather, “How does that platform integrate then with the rest of the architecture or the rest of the IMD space?” So, that the data collected, either to or from the Stryker, can be shared with other sensors in the array on the battlespace, and then the old over-used cliche of one plus one can equal something greater than two, kind of incorporating that into the larger air picture.

On the higher end, I don’t want to get too much into… I used to work the counter-hypersonics portfolio for the company, and I would say that, I’ll just leave it very quickly and say that, getting to some kind of a space-based capability for sensing and for the hypersonic threat is certainly something that we’re working with customers on, as well, and hearing loud and clear that that has to be front and center in trying to solve the hypersonic challenge. So, I think a system like IBCS certainly can link data and information from any number of sources, and the future potential of something like this is really exciting when we think about it.

Tyler: When you say hypersonics, and honestly, we talked about all of this because any peer state’s going to layer a bunch of threats in at once, right? I mean, it’s not going to be a la carte, what we’re going to be facing in the future, as in one thing happening at a time and decisions are made, and an action happens. When you talk about hypersonics and you talked about very low-end threats and whatever’s in the middle that we’re probably more used to, time becomes the issue, right? How can the human being look at all that, figure it out, and actually put a countermeasure in place to stop it and do it thoughtfully? Do you see the system, obviously being monitored by people, but do you think it can operate automatically in a very high volume scenario?… Can you put that thing on automatic, and will shoot until there’s nothing left? Do you see this having that ability if it was needed during a peer state attack?

Kenn: The platform does have that capability, Tyler, and I think that the tactics and techniques and procedures, I don’t wanna speculate on because that’s not mine to do, but the capability certainly resides, and how it’s put into action would be certainly up to the, as you can imagine, to our customers, so maybe they’d be best to answer that. But one thing I do want to mention that may be a tangent of the question you just asked, is this idea of long-range precision fires… We’re making investments today to broaden the capabilities of an IBCS-like architecture to further enable multi-domain operations, not only from a defensive standpoint, but to have the potential for enhancing capabilities like long-range precision fires on the offensive side, as well.

So, I don’t want to leave you with the notion that this platform is strictly defensive because I think all of the goodness that goes into a system like an IBCS or an IBCS-like system is… Is certainly it’s within the technological capability of a system like that to then also be used to calculate long-range precision offensive fires as well, so it’s on offense and defense. We’re hearing a lot more from, I think, the department and our customers about the need to do that, and this system certainly would have that offensive/defensive capability, as well.

Tyler: Okay, so I have two questions based on both of those capabilities, offensive and defensive. One is getting to the low observable [stealth] issue. Stealth technology is proliferating, we’re no longer just the only people that have this capability, especially in the cruise missile realm, not just on the higher-end exquisite aircraft realm. Being able to link all those disparate sensors together and look at a common picture… Does that also get you a much better fidelity target track? Considering it is made up of data from multiple sensors, instead of a bunch of federated sensors and systems, that may be data linked together to some degree, but that data is not so well fused?

Author’s note: Simple English version of this question is can a networked and data-fused system like IBCS help spot, track, and even possibly engage stealthy aircraft and cruise missiles.

Kenn: Yeah, I think you’ve obviously been a designer on the system, Tyler. I think you just nailed it, nailed the, really what’s at the acme of the fusion, without getting too technical, which I won’t try to do with you, because I’ll fail, but also it gets into some of the classified realm, which we certainly don’t want to do. But yes, in essence, you’re right, when you fuse the data from disparate systems, I think you have a lot more fidelity in the track. And that’s some of the, I’ll just say, secret sauce of this system is the ability to fuse that information into a more refined fire control track, which we have, very proud to say seven for seven in-flight tests, including last month where we, in two consecutive weeks, knocked two very sophisticated targets out of the sky with the system, it was a very complex scenario. And again, during the Army’s limited users test that we were a part of.

Tyler: So, on the offensive side… The ability to take all that, kind of what we think of as a defensive capability, as you said, and migrate it to being able to punch the enemy, too… Obviously, there are some new interesting things that the Army is working on, penetrating airborne assets like FARA [Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft] and different capabilities that are manned, potentially unmanned, or optionally manned. Do you see a system like this or even this system in the not so distant future, being able to push its data out to those forward nodes that might be airborne downrange instead of on the ground next to some command or control capability, but they’re airborne and be able to rapidly respond to threats when they may represent the most efficient way to deal with those threats based on what’s nearby or what type of capability they possess?

Kenn: Yeah, it’s a great question. And I think I would maybe comment on it this way. I think a system like this… And go back to how it’s built, it’s MOSA network-enabled, it can play a critical role in these emerging JADC2 capabilities, offense and defense-wise. And it has the capability to be extensible to integrate with other networks and C2 [command and control] capabilities that are out there. So, back to an earlier question about will this being sort of the be-all-end-all or will it be part of a larger network? I think it’s probably the latter. However, the example I always give and have heard folks talk about, particularly in recent weeks in an Air Force context… Is that you can envision a system like an IBCS that helps to link either pull or push or pass data from a ground node to a ship at sea or to an F-35 or to an over horizon Special Operations Airman that’s deployed somewhere far, far away. I think this system has the ability to do that. And so it can be extensible to other networks and systems and pushed far beyond its own capability for what the Army is going to use it for… If that maybe gets at where your question was going.

Tyler: So the last question I have is about electronic warfare. And I know there are limitations in how much you can talk about this. But a lot of times when we hear “network, network, network,” there’s so many incredible benefits from it. And that’s absolutely clear and very well articulated by a lot of people… But what a lot of people ask is, what about vulnerabilities in depending so much on an integrated network. And with this [IBCS], you’re talking about really fast decisions, multiple sensors, waveforms, etcetera, etcetera. How do you guys look at the EW picture and the stability of such a system in regards to this, let’s say, threat?

Kenn: Well, you’re asking some really, really great questions first of all, which I know are based on how you write and what you write about, you’re pretty well versed in the problem set, which is your job to do, so good on you. The EW issue, the challenge is certainly a real one. I guess I would refer you back to the flight test, I think on the 13th of August, when our customer recognized the same thing you did in your question and said, “Hey, we’re gonna put… We’re gonna really make this hard for the system to figure this out.” And, again, I can’t get into the specifics as you understand, but we made it really challenging and tried to bring down these connected issues that were holding together this network. And the system found a way out of it, it would recognize that it was under some kind of an attack or at least some kind of an incursion to prevent it on its most natural path to pass data, and it found a way to get around it. So, through other connections and networks, which was really, really impressive to see. And the really impressive part is it barely missed a beat.

I don’t wanna get… I ask you not to put the specifics in if anything you’re gonna write about, but I will just say that in a matter of seconds… I was in the control room watching everything happen, I knew when the EW activity was going to begin and I could see through the sensors and the screens… It was temporarily made to be disoriented and pretty quickly was able to find another path and another channel to get the data where it needed to go and passed a fire control solution to a shooter, which took a first shot and nailed it. And that was eye-watering to me.

Now it’s not to say that that’s representative of every EW scenario that might be had out there, no, but I think it was proof that the system has the capability to work its way around problems like that, because those problems will exist clearly, as you said, particularly a conflict, a sophisticated conflict, threats are gonna come from all ways and shapes and sizes, from all angles, and it’s going to be very difficult, so these systems have to find their way out of these problems. And I’m really, really, really proud to say that the team and working with the Army, we found a way out of the one during the test. I refer you back to them for specific details on it, but just to paint a little picture of what I saw.

Editor’s note: We want to thank Kenn Todorov for taking the time to really dig in on this challenging topic. We also want to thank Bridget Slayen of the Northrop Grumman’s comms team for facilitating the exchange.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com