Russia says it will set up a new, long-range over-the-horizon radar system to help “control” the Arctic by providing additional early warning and monitoring capability with regards to various potential threats, including aircraft, cruise missiles, and hypersonic weapons. This announcement comes just over a week after the head of U.S. Northern Command, who is also in charge of the U.S.-Canadian North American Aerospace Defense Command, called for revitalization and expansion of similar American capabilities in this ever more strategic region.

The Russian Ministry of Defense revealed that the next 29B6 Konteiner radar would be installed in the Arctic on Dec. 2, 2019, according to state media outlet TASS. The day before, the first Konteiner radar, situated in the semi-autonomous Russian republic of Mordovia, officially began operations, six years after Russia finished building that system. From there, it provides early warning and general monitoring coverage of Russia’s western flank, reportedly including most of Europe and portions of the Middle East.

“Further development [of 29B6 sites] is possible towards control of the Arctic,” Mikhail Petrov, Konteiner’s chief designer, told TASS. “This is what we are dealing with at present and this task is being actively considered.”

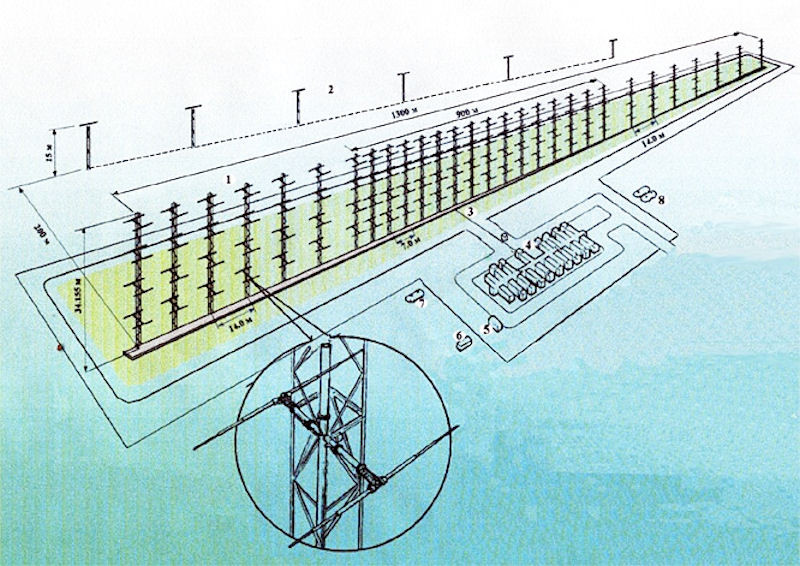

Konteiner is an extremely large, bistatic system consisting of separate high-frequency transmitter and receiver arrays. The complete transmitter array, which has 36 masts, is just over 1,440 feet wide, while the 144 masts that make up the receiver are spread across an area 4,265 feet wide. The transmitter and receiver sites in Mordovia are around 186 miles from each other.

The system provides fixed coverage in one particular direction across a 180-degree arc. It can reportedly detect and track objects right up to the edge of space and between 1,240 and 1,864 miles away, depending on the size and type of the target, as well as weather and other atmospheric conditions. The 29B6 radar bounces its signals off Earth’s ionosphere, an upper region of the atmosphere, to detect targets at such extreme ranges. It does also mean that it is blinded to threats outside of its field of view, though.

These types of over-the-horizon radars are useful for tracking the movement of targets at extended distances, but do not provide the necessary fidelity to actually cue surface-to-air missiles or anti-missile interceptors to shoot them down. They do, however, provide valuable early warning of potential threats as part of an integrated air defense network, so that aircraft, ships, and other ground-based sensors can work identify and possibly engage them. Their range means they can also be positioned further inland, making them less vulnerable to short and no-notice attacks.

Setting up a second 29B6 system somewhere in northern Russia pointed toward the Arctic would make good sense and could potentially provide a wide-reaching, if more generalized capability to monitor for air and missile threats in the increasingly important region. Konteiner’s range could allow it to be positioned in a more hospitable environment rather than a location well above the Arctic circle, where it could be expensive and complicated to build and maintain the necessary facilities.

It would still be linked to the larger Russian integrated air defense network, which would include smaller ground-based radars, aircraft, and ships based at a growing number of rehabilitated or all-new Arctic facilities that the country has been building in the past few years. Some of these air bases are already supporting increased numbers of aerial patrols in Russia’s far north, which could benefit from the general information the 29B6 would provide to immediately identify potential tracks of interest.

It’s not clear exactly how capable Konteiner actually is at spotting and tracking low-flying cruise missiles or modern hypersonic threats, such as boost-glide vehicles or air-breathing hypersonic missiles. Regardless, it would still provide important additional long-range radar coverage toward the Arctic.

The Kremlin’s focus on using the 29B6 to monitor for these threats from that region, as well as from other vectors, could indicate that Russia is increasingly concerned about American air- and sea-launched hypersonic weapons. This includes missiles that will eventually be available for some U.S. Navy submarines that could hide under the Arctic ice before launching a strike.

Though the Russians have no specifically highlighted this capability, as a lower frequency radar system, the 29B6 could have the ability to at least detect the presence of incoming stealth aircraft or missiles. It is important to note that bistatic low-frequency active and passive radars do not negate stealth technology and the 29B6 would not be able to provide accurate enough information for an engagement quality radar track.

Russia isn’t the only one concerned about its Arctic flank being exposed, either. On Nov. 23, 2019, U.S. Air Force General Terrence John O’Shaughnessy, commander of U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM) and the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), raised concerns about limited U.S. military situational awarness in the region at the Halifax International Security Forum in Washington, D.C.

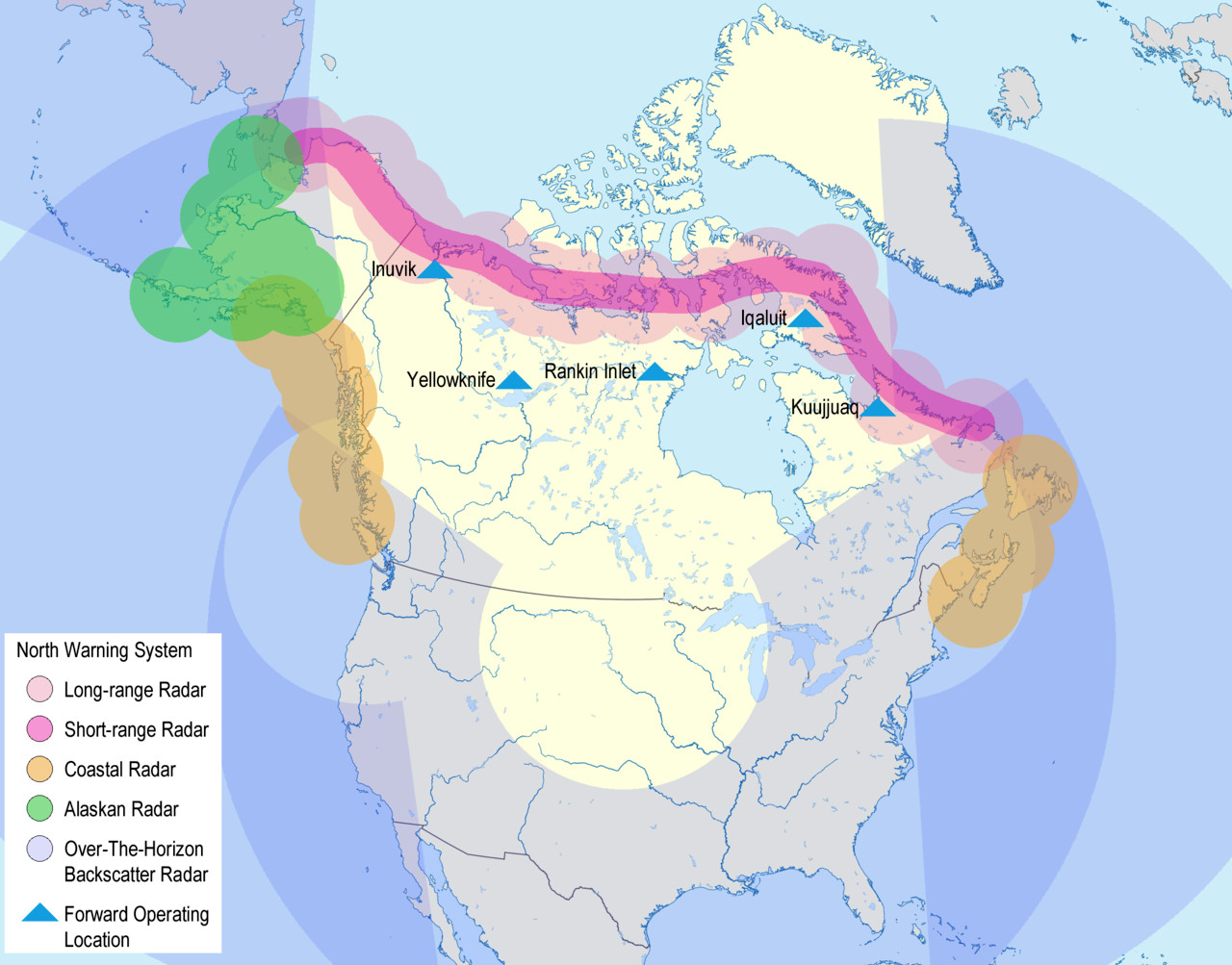

“We have to be aware of what is happening in that environment,” O’Shaughnessy said. At present, NORAD relies heavily on the North Warning System (NWS), which includes 15 AN/FPS-117 long-range radars and 39 AN/FPS-124 short-range radars positioned across northern Canada. The NWS is the successor to the Cold War-era Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line, a significant portion of which was deactivated as part of the transition process in the late 1980s.

The U.S. military also operates a number of large phased-array radars, primarily designed for detecting and tracking ballistic missiles, some of which provide coverage over the Arctic. These include Solid State Phased Array Radars in Alaska, Greenland, and the United Kingdom. These terrestrial sensors are further bolstered by space-based early-warning assets, an area where Russia has historically had much less capacity.

Unfortunately, the foreboding environment makes improving ground-based U.S. early warning capability in the Arctic, including to be able to better spot cruise missiles and hypersonic weapons, which the Pentagon also sees as growing threats, as difficult for the United States as it is for Russia. “We’ve done this before,” NORTHCOM and NORAD chief O’Shaughnessy said. “Simple things become hard,” he added, citing specifically how satellite communications become more difficult above 65 degrees parallel north latitude due to how the satellite constellations are situated in orbit. Whether this means the United States may also turn to over-the-horizon radars, as the Russians appear to be, or focus more on other terrestrial capabilities or simply expanding polar satellite early warning coverage instead remains to be seen.

It’s also not clear when Russia’s 29B6 radar pointed toward the Arctic may become operational. Russia began developing Konteiner back in 2007 and only finished building the first site in 2013. As noted, it then took another six years for the system to pass a variety of testing and evaluation before becoming operational. At the same time, this experience with the initial example of the system has no doubt provided lessons learned that could help speed up the construction and activation of future arrays.

Regardless, the announcement underscores Russia’s steadily increasing efforts to expand its force posture and overall military capabilities in and around the Arctic region.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com