With Ukrainian officials continuing to warn that Russia might be just weeks away from launching a new major military intervention against their country, the relative military strengths of the two countries are currently under wider scrutiny. Were Moscow to initiate a new offensive against its neighbor, it is likely to draw upon the approximately 175,000 troops among the ground forces that are expected to be deployed in the region, as well as missile strikes and potentially naval elements. But Russia would not attempt any significant military action without extensive use of airpower. With that in mind, now is a prime opportunity to take a detailed look at the respective aviation assets that can be brought to bear by Russia and Ukraine in the region, and how their capabilities compare.

Russian military aviation assets

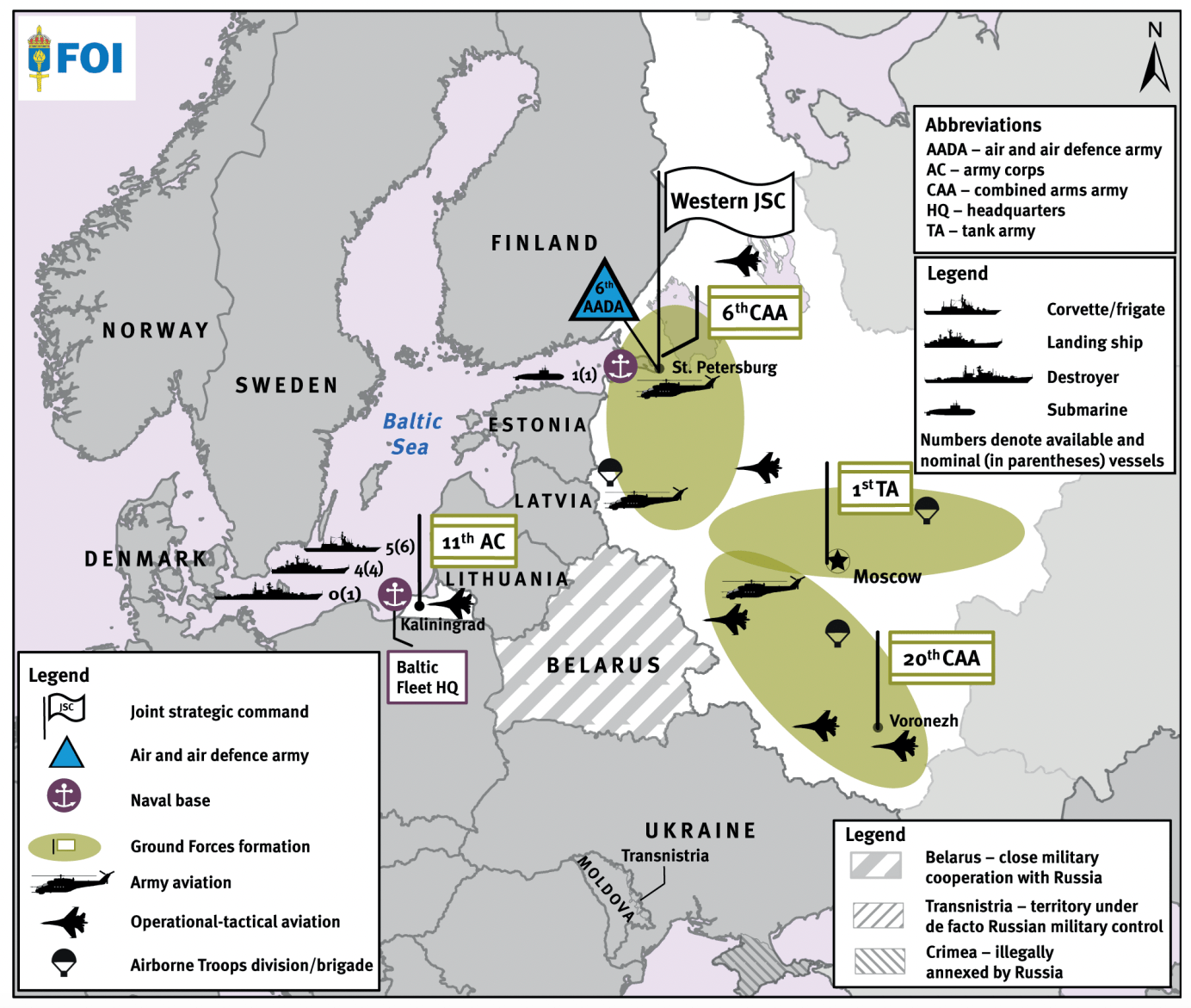

The Russian Armed Forces are organized within five military districts, which are administrative organizations based on geographical territories, each with a headquarters that administers the military formations based in that region. In a worst-case scenario for a new Russian intervention, as outlined by Ukrainian military intelligence in November, Russian forces would cross the Ukrainian border from the east and attack via annexed Crimea in the south, as well as launching an amphibious assault on the city of Odessa. An attack from Belarus in the north is also possible but would involve troops that have not yet arrived in the region. Regardless, any such plan would likely involve ground forces — and air assets — from two separate military districts.

Much of Russia’s border areas with Ukraine, as well as the critical frontiers with the NATO member states of Poland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, come under the military responsibility of the Western Military District, or WMD. This is unsurprisingly the most important of Russia’s territorial commands, and it also covers Moscow and St. Petersburg, various important industrial areas, and the heavily militarized Kaliningrad exclave.

As well as the Russian Aerospace Forces, or VKS, units in the western region, the WMD is responsible for Russian Ground Troops within the region, as well as the entire Baltic Fleet, which also includes its own aircraft units. In the case of a full-scale war, the WMD would also assume control of relevant Russian Federal National Guard Service (Rosgvardia) units, the border guard troops of the Federal Security Service (FSB), and the Ministry of Emergency Situations (MChS).

With responsibility for the defense of Moscow and St. Petersburg, the WMD has the most capable ground-based air-defense coverage in Russia, with protective zones around these cities as well as Kaliningrad. These air defense systems can counter both aircraft and cruise missiles as well as tactical and even — in the case of the Russian capital region — to a limited degree strategic ballistic missiles.

WMD Fixed-Wing Aviation

When it comes to the VKS units subordinated to the WMD, these come under the command of the 6th Air Force and Air Defense Army, or 6 A VVS PVO, an organization that only came into being in 2015. The 6 A VVS PVO includes strategically tasked ground-based air defense units, as well as tactical combat aircraft (known in Russia collectively as Frontal Aviation), and Army Aviation helicopters, which are expected to operate in close concert with Russian Ground Troops.

Within the 6 A VVS PVO is a single composite division, the 105th Composite Aviation Division (105 SAD), which includes all the WMD’s fighters and strike aircraft, plus an independent composite transport regiment, which mainly conducts VIP and liaison missions. The Army Aviation component has one brigade and two regiments for a total of 10 helicopter squadrons, including units equipped with types capable of performing attack, air assault, and transport tasks.

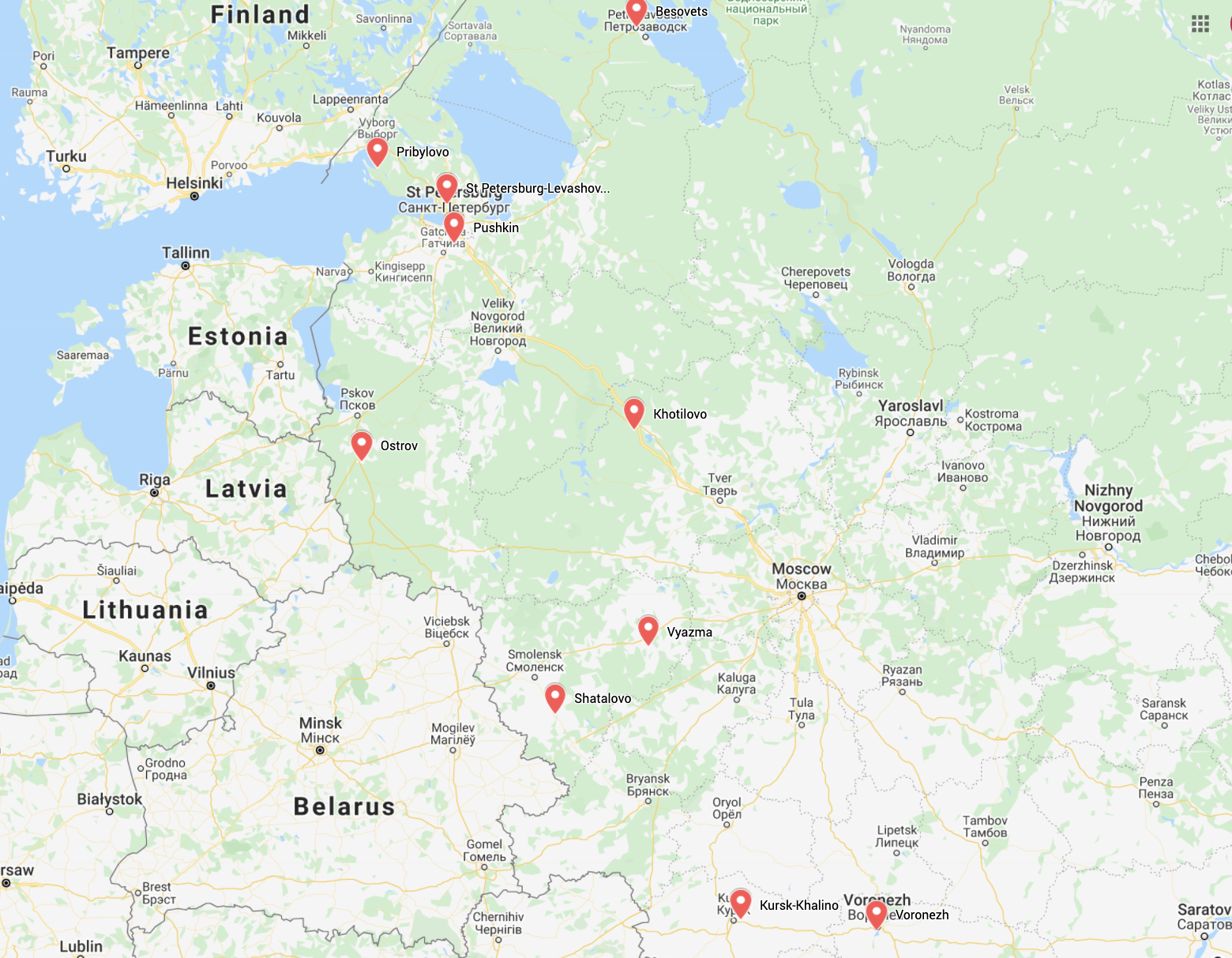

The following airbases are employed permanently by the WMD, and at least some of them would be expected to play a role in any large-scale military operations involving this military district. While some of these facilities are farther away from the Ukrainian border, they could still send aircraft to contribute, or could forward-deploy their assets:

Kursk-Khalino: The 105 SAD’s 14th Fighter Aviation Regiment (14 IAP) has two fighter squadrons, both flying the two-seat Su-30SM. The regiment has a nominal strength of 24 Su-30SMs, which replaced around 30 MiG-29SMT/UB Fulcrum fighter jets that had been incorporated into the VKS after their rejection by export customer Algeria. The status of the Fulcrums is a little unclear: They appear to have become non-operational after delivery of the Su-30SMs, but then appeared again earlier this year in Syria, as part of a combat deployment.

MiG-29SMT jets from Kursk-Khalino take part in a Victory Parade flight to St. Petersburg-Levashovo in 2017:

Voronezh: The tactical bomber capabilities of the 105 SAD rest with the 47 BAP, which has two squadrons of Su-34 Fullbacks — frontal bombers in Russian terminology — at Voronezh. The regiment received 24 Su-34s to replace its previous Su-24M fleet, and the Fullbacks were among the first to deploy to Syria for combat operations. Unusual among VKS units, the 47 BAP has extensive combat experience in the delivery of precision air-to-ground munitions, including laser and TV-guided bombs and missiles and satellite-guided bombs employed in Syria.

Besovets: Part of the 105th Composite Aviation Division, the 159 IAP includes two squadrons flying the single-seat Su-35S Flanker multirole fighter. The regiment operates 24 Su-35S jets which replaced previous-generation Su-27Ps and modestly upgraded Su-27SMs. As such the Besovets unit is reflective of the wider re-equipment program that has invested the WMD with new fighters featuring more modern capabilities, including multi-role capability, precision-guided munitions, and improved avionics and navigation/attack systems.

Khotilovo: Another 105 SAD regiment, the 790 IAP has three fighter squadrons flying a mix of Su-35S jets and MiG-31BM Foxhound interceptors. This was the second WMD regiment to get the Su-35S, after the unit at Besovets, again replacing a previous fleet of Su-27P/SM/UB jets. Alongside the 12 Su-35S assigned to one squadron, the other two 790 IAP squadrons between them operate a total of 24 upgraded MiG-31BM/BSM interceptors. These provide the WMD with a significant long-range air-defense capability, including the ability to engage low-flying cruise missiles, a capability that Ukraine does not currently possess.

Shatalovo: One of two direct-reporting units, the 4 ORAE is a dedicated reconnaissance squadron flying six to eight Su-24MR Fencer fast jets, as well as a smaller number of An-30 twin turboprops used for photo-survey. The fact that only a single squadron is responsible for all tactical reconnaissance aircraft in the WMD is perhaps surprising, but assets would likely be deployed to the region from elsewhere in Russia during an actual conflict.

St. Petersburg-Levashovo: Another direct-reporting unit, the 33 OTSAP is an independent composite aviation regiment with two composite transport squadrons at these two bases, Levashovo outside of St. Petersburg and Semyazino east of Moscow. These operate a diverse array of An-26, An-12, An-72, Tu-134, An-148, L-410, Mi-8, and Mi-26 aircraft.

WMD Army Aviation

Ostrov: Part of the WMD’s Army Aviation branch, the 15th Army Aviation Brigade (15 Br AA) at Ostrov has two attack helicopter squadrons with Ka-52 Hokum and Mi-28N/UB Havoc rotorcraft, two assault transport squadrons with Mi-8MTV-5-1 Hips, as well as a detachment of Mi-26 Halo heavy transport helicopters that together provide a significant aerial assault capability.

Vyazma: This base is home to Army Aviation’s 440 OVP, the second of two independent helicopter regiments. It consists of two attack (Ka-52 and Mi-24P) squadrons and one assault transport squadron (Mi-8MTV-5-1), as well as an electronic warfare (EW) detachment, the latter equipped with the Mi-8MTPR-1. While there are few airborne EW assets directly attached to the WMD, extensive electronic warfare operations have been a feature of recent Russian campaigns in the Middle East and would be expected to feature heavily in a new offensive in Ukraine.

Pushkin and Pribylovo: These two bases together support the 549 OVP, one of the WMD’s two independent helicopter regiments. This Army Aviation formation consists of one attack, one assault transport, and one composite (equipped with a mixture of attack and assault transport helicopters) squadron. Between them, these fly the Mi-24P and Mi-35M Hind, Mi-28N/UB, and Mi-8MTV-2/MTV-5-1.

It’s notable how few tactical strike assets are permanently assigned to the WMD. The spearhead is the 47 BAP, with its Su-34s based at Voronezh. Were offensive operations to be launched over Ukraine, it’s likely that these would be supplemented by additional Su-24 and Su-34 units deployed from other bases in Russia. At the same time, the shift to the multirole Su-35S and Su-30SM means that these fighters are increasingly able to fly air-to-ground missions, too.

One Frontal Aviation aircraft type that is ‘missing’ from the WMD is the Su-25 Frogfoot ground-attack aircraft, which was widely used in Syria. In the past, plans were announced to establish an attack regiment with Su-25s at Buturlinovka, but this has never taken place. Again, however, Su-25s from elsewhere in Russia would likely be deployed to the WMD to support potential operations over Ukraine.

In its favor, the 6 A VVS PVO includes some of the best trained VKS units, with regular live-fire exercises in the region, including the large-scale Zapad-21 maneuvers that took place earlier this year and involved around 80 aircraft and helicopters. In addition, Russia’s long-running campaign in Syria has exposed a significant proportion of airmen — reportedly over 90 percent — to combat operations, with some of the most experienced pilots having accumulated more than 400 combat sorties, according to Russian Minister of Defense Sergei Shoigu.

However, it should be noted that the majority of experience in air-to-ground scenarios — whether during training or in the Syrian campaign —has been gained in the employment of unguided bombs and rockets, as well as cannon fire, with only limited use of guided air-to-surface missiles or bombs.

A significant capability within the 6 A VVS PVO is the ready availability of Army Aviation units, which would be critical to supporting any kind of ground campaign. Overall, the Army Aviation branch within the WMD has been expanded significantly in recent years. In late 2013, for example, there were four or five frontline squadrons, while that number has since increased to 10, which are responsible for a fleet of between 180 and 200 helicopters.

Within the WMD specifically, these units deliver a significant punch, with no fewer than five attack helicopter squadrons, another four squadrons with armed assault transport rotorcraft, and a composite squadron that operates a mixed fleet of attack and assault transport helicopters. The equipment they operate is notably advanced, including Ka-52, Mi-28N/UB, and Mi-35M attack helicopters which offer night and adverse-weather capabilities and feature anti-tank guided missile (ATGM) armament.

A tactical flying exercise in the Western Military District involving Mi-8, Mi-24, and Ka-52 helicopters from Vyazma airbase:

For troop transport, the WMD has immediate access to around 80 examples of the Mi-8MTV-5-1, among the most modern versions of the venerable Hip helicopter.

In terms of fixed-wing transports, the WMD has only limited capabilities within its ranks, with a handful of obsolescent An-26 and An-12BK transports available for general cargo and troop transport. However, more transport capacity can be drawn from the various units of Transport Aviation, a separate branch of the VKS, with its bases all located further east. The same applies to aerial refueling assets, with no tankers being assigned to the WMD. Instead, any aerial refueling capacity would have to be provided by Long-Range Aviation, which also trains regularly with Frontal Aviation assets.

Southern Military District

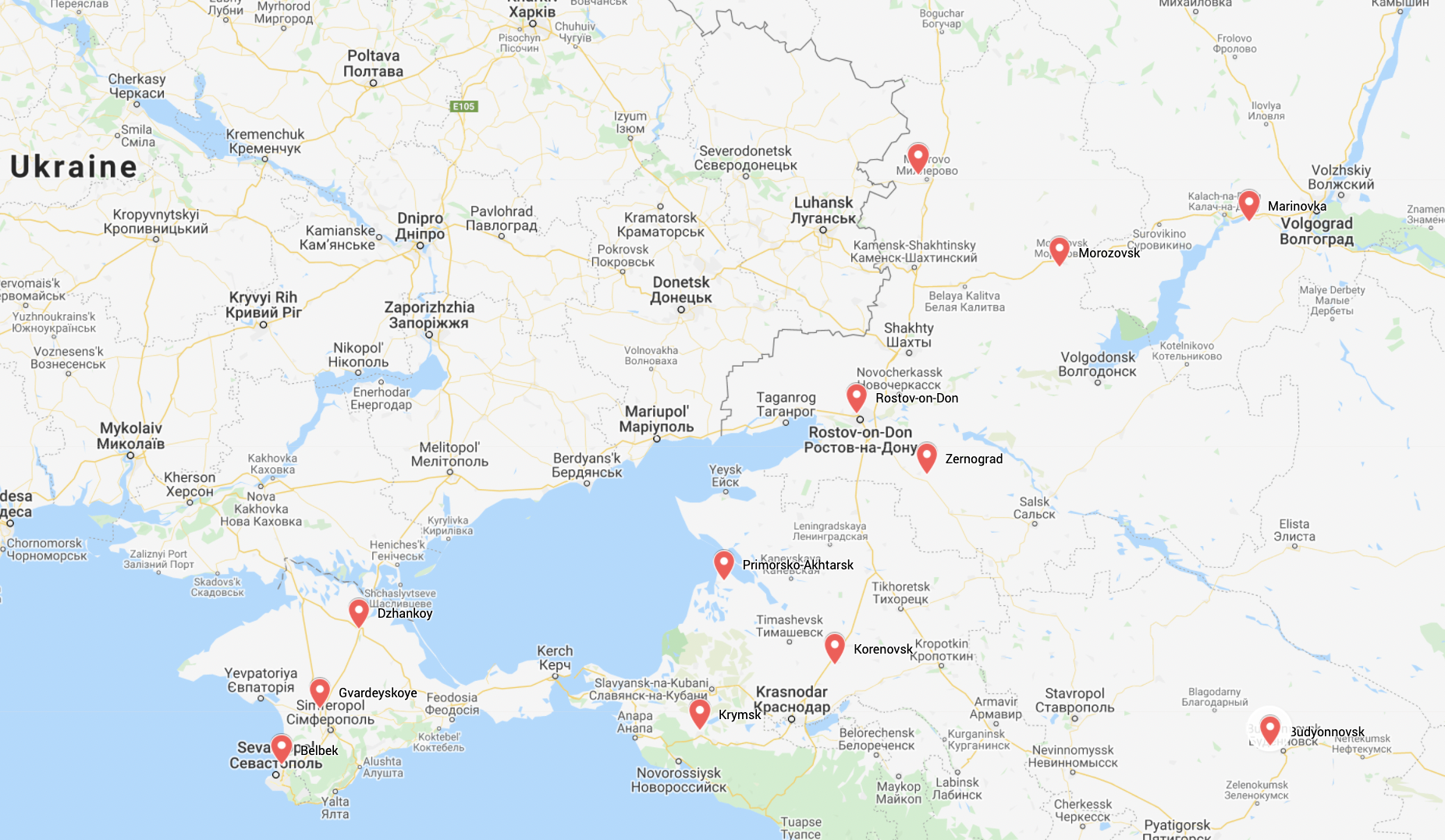

In addition to the WMD facing Ukraine in the west, certain aviation units of the Southern Military District (SMD) also potentially play into the Ukraine equation. The air assets within this command fall under the command of the 4th Air Force and Air Defense Army, or 4 A VVS PVO.

SMD Fixed-Wing Aviation

It was units from the 4 A VVS PVO that bore the brunt of the fighting in Chechnya in the 1990s and early 2000s, later took part in the war with Georgia in 2008, and — most important for this analysis — were involved in the seizure of Crimea from Ukraine in 2014. For this reason, elements of the 4 A VVS PVO remain at high readiness in case the conflict with Ukraine escalates.

In comparison to the WMD, the strike components of the SMD are somewhat stronger, with two regiments of Su-24/Su-34 tactical bombers, two regiments of Su-25 attack aircraft, plus a brigade and two regiments of Army Aviation helicopters. At the same time, MiG-31 interceptor units are absent.

Since the annexation of Crimea, a new composite division has been established on this territory, with three aviation regiments. This is the 27th Composite Aviation Division (27 SAD), with its headquarters in Belbek, Crimea.

The 27 SAD consists of flying units at the following bases:

Gvardeyskoye: Home to the 37th Composite Aviation Regiment (37 SAP), this consists of two squadrons: a bomber unit with Su-24Ms, and an attack unit with upgraded Su-25SM aircraft.

Belbek: The 38th Fighter Aviation Regiment (38 IAP) at this base has two fighter squadrons. The first of these is equipped with Su-27SM fighters, while the second operates Su-27SM3 and Su-30M2 fighters.

Dzhankoy: The rotary-wing regiment in Crimea is the 39th Helicopter Regiment (39 VP), which received one squadron with Ka-52s, a second with Mi-28N and Mi-35M helicopters, and a third with the Mi-8AMTSh.

In addition to these, further strike capabilities are provided by the Russian Navy, which has the 43rd Independent Naval Attack Aviation Regiment (43 OMShAP) stationed at Saki in Crimea. This regiment flies 12 Su-30SMs, six Su-24Ms, and six Su-24MRs, and came to prominence during several encounters with NATO forces in the Black Sea earlier this year.

While the SMD units can be immediately brought to bear in a potential conflict in Ukraine, due to their locations in Crimea, the SMD has other aviation units that it can call upon too, also under the command of the 4 A VVS PVO. Some of these are based outside Russian borders, in Armenia, but those in Russia are as follows:

Krymsk: Part of the 1st Composite Aviation Division (1 SAD), the 3rd Composite Aviation Regiment (3 SAP) at Krymsk operates two squadrons of Su-27SM(3) fighters and a handful of Su-30M2 trainers, one squadron of non-upgraded Su-27s, plus a detachment of Ka-27 helicopters.

Millerovo: Also under the 1 SAD is the 31 IAP at Millerovo. Formerly a MiG-29 operator, it has upgraded to the Su-30SM, with a total of 24 aircraft divided between two squadrons. Located less than 20 miles from the Ukrainian border, this base was involved in the fighting in Donbas in 2014.

Budyonnovsk: The 368th Attack Aviation Regiment (368 ShAP) under the 1 SAD is a long-term operator of the Su-25, flying the type in Afghanistan in the 1980s. After transferring one Frogfoot squadron to Gvardeyskoye in Crimea it now has two squadrons with upgraded Su-25SM and Su-25SM3 aircraft.

Morozovsk: Last of the 1 SAD regiments is the 559th Bomber Aviation Regiment (559 BAP) which has three squadrons with a total of 36 Su-34 aircraft, making it one of the most powerful tactical bomber units within the entire VKS. The unit is another which has considerable experience in the Syrian campaign.

Marinovka: Marinovka near Volgograd is home to the 11th Composite Aviation Regiment (11 SAP) flying the Su-24M and Su-24MR.

Primorsko-Akhtarsk: Another Su-25 unit is at Primorsko-Akhtarsk, the 960th Attack Aviation Regiment (960 ShAP) having fought in Chechnya and in Georgia.

Rostov-on-Don: The transport aviation assets of the SMD are found within the 30th Independent Transport Composite Aviation Regiment (30 OTSAP) at Rostov-on-Don. It has a mixed fleet of fixed-wing types (An-12 and An-26 aircraft, plus smaller numbers of An-148, Il-22, L-410, and Tu-134), as well as a helicopter squadron with a dozen Mi-8 and Mi-26 helicopters.

SMD Army Aviation

The Army Aviation units within the SMD follow a very similar pattern to their counterparts in the WMD. There is a single brigade, the 16th Army Aviation Brigade (16 Br AA), at Zernograd with two squadrons of Mi-8 transport helicopters, two squadrons of Mi-28N and Mi-35M attack helicopters, and a detachment of Mi-26 heavy transport helicopters. Then there are also two independent Army Aviation regiments. These are the 55th Independent Helicopter Regiment (55 OVP) at Korenovsk with a squadron of Mi-8AMTSh transport helicopters, a squadron of Mi-28N and Mi-35M attack helicopters, and a squadron of Ka-52 attack helicopters, and the 487 OVP at Budyonnovsk that has a transport squadron with Mi-8AMTSh and Mi-8MTV-5 helicopters and two combat squadrons with Mi-24s, Mi-28Ns, and Mi-35Ms. Army Aviation helicopters proved an important component in the earlier seizure of Crimea.

Ukrainian military aviation assets

Against the might of the WMD and SMD, not to mention other Russian-based VKS units that are available to support them, Ukraine’s airpower might seem entirely mismatched. While Western sources credit the Ukrainian Air Force, or PS, as being Europe’s seventh-largest air force, this still amounts to approximately 200 aircraft of all types — compared to around 1,500 combat aircraft for Russia’s air arms. Furthermore, the majority of the PS fleet is made up of Soviet-era aircraft. While local upgrade programs have been launched to address obsolescence issues, they have had mixed results. On the other hand, there are extensive stocks of spares and aircraft that can be returned to service as well as experienced local overhaul and maintenance facilities and Ukraine has made efforts to bolster its capabilities since the fighting began in 2014.

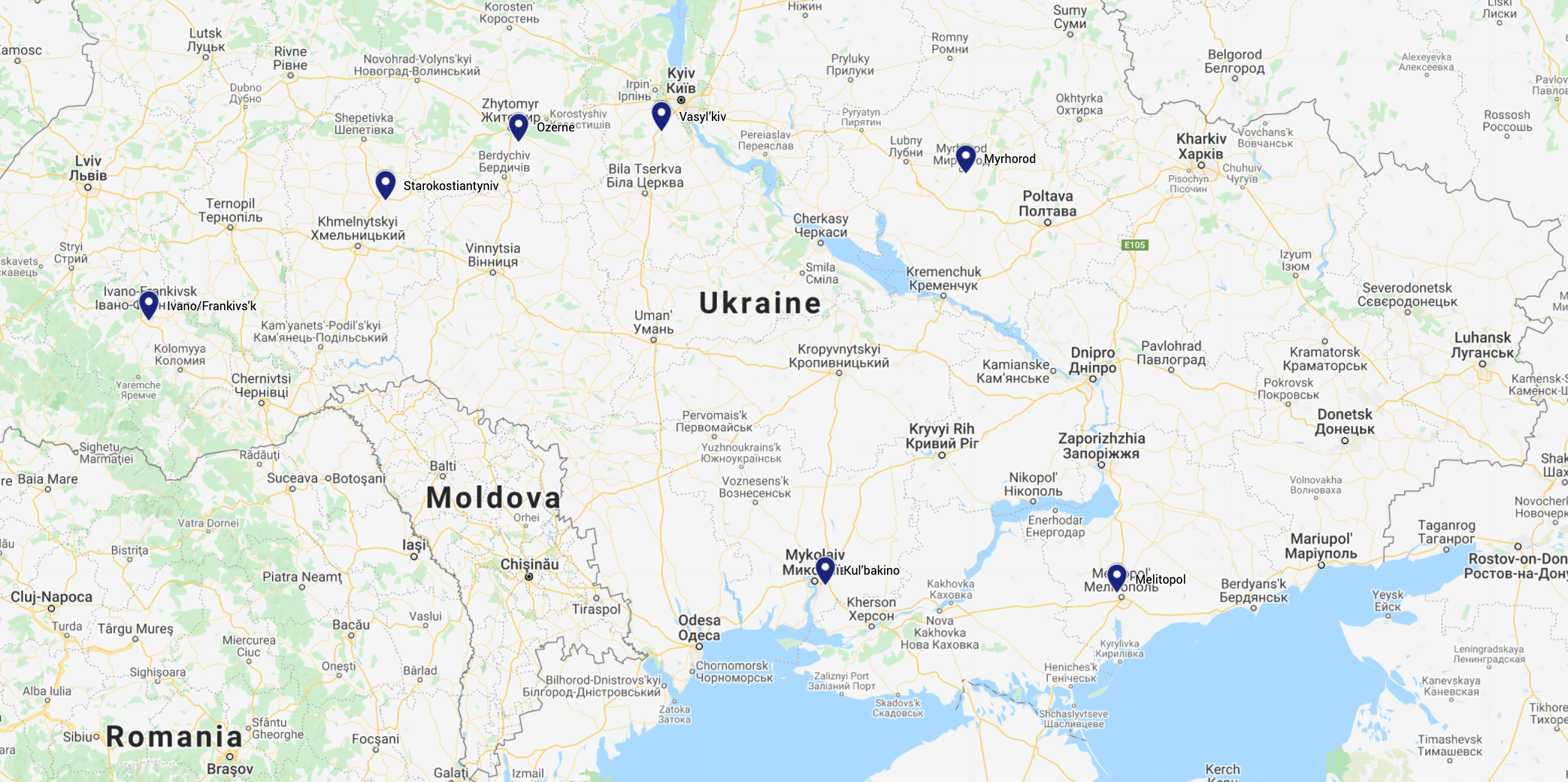

Around 50 MiG-29 fighters survive with the PS, and these are assigned to two regiments, the 40th Tactical Aviation Brigade (40 brTA) at Vasyl’kiv and the 114 brTA at Ivano/Frankivs’k.

Approximately 32 Su-27s survive with another two regiments, at the 831 brTA at Myrhorod and the 39 brTA at Ozerne.

A single Ukrainian base, Starokostiantyniv, operates a dwindling number of Su-24Ms and Su-24MRs, perhaps a dozen in all, assigned to the 7 brTA. That same base is now also operating the Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 armed unmanned aerial vehicles, which have seen recent combat in the east of the country.

In common with Russia’s SMD, the PS also still operates the Su-25, with the 299 brTA at Kul’bakino airbase near Mykolayiv. Surviving aircraft have been upgraded with new navigation equipment, while chaff/flare launchers were added in the wake of the hostilities in Donbas, during which Su-25s were temporarily detached to Dnipropetrovsk International Airport. Five Su-25s were lost during the fighting in 2014, but they were replaced by returning to service aircraft from storage.

Transport assets of the PS are concentrated with the 25th Transport Aviation Brigade (25 TrAB) at Melitopol, which includes examples of the An-26 as well as around seven Il-76MD Candid airlifters, which provide a significant airlift capability, including the ability to deliver paratroopers and airdropped cargoes.

Unlike its Russian counterpart, Ukrainian Army Aviation is a separate branch and not part of the air force. It relies almost exclusively on older versions of the Mi-8 and Mi-24, with around 50 Hips and 30 or more Mi-24s currently active.

The Ukrainian Navy has for long provided little more than a token force, based at Kul’bakino and heavily optimized for coastal maritime work. Earlier this year, however, the service also began to receive Bayraktar TB2 drones.

Airpower against the odds?

On paper, Ukraine’s available airpower is hardly a match for just one Russian military district, let alone the VKS at large. However, Ukraine has gained valuable combat experience from the conflict in the east of the country. Ukrainian pilots are aware of the threat posed by man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS) and other air-defense systems that have been fielded by pro-Russian forces during that campaign. But back in 2014, the threat posed by short-range air-defense systems effectively grounded the PS and Ukrainian Army Aviation, and Kyiv has been reluctant to deploy significant air assets in the eastern Donbas region since then.

At the same time, the extent of the Russian ground-based air-defense ‘umbrella’ is such that, with the forward deployment of additional assets — something that is routinely practiced — it could reach far into Ukrainian territory even from the Russian side of the border, creating a ‘sanitized’ zone in which opposing air operations were made almost impossible. All this would be further enabled by the availability of A-50 Mainstay airborne early warning aircraft, providing a lookdown capability from on high and filling in any gaps in ground-based radar coverage caused by terrain.

As part of this strategy, Ukrainian airbases and any stationary radars or command posts would also be prime targets for standoff strikes using air and ground-launched missiles, which include ballistic Iskander-M types, as well as Kalibr cruise missiles launched by the Black Sea Fleet, further hampering Ukrainian counter-air operations. Russia’s Long-Range Aviation, which is increasingly adding conventional weapons to its arsenal, could launch additional cruise missile strikes. Overall, Russia’s standoff cruise missile capabilities and overall capacity have evolved a lot in the last decade or so and would allow Moscow to limit the risk to manned assets when striking fixed targets farther west.

First flight of the latest upgraded Tu-95MSM strategic bomber/missile carrier:

With that in mind, Ukraine may well respond to a large-scale Russian intervention on its territory by instead keeping its limited manned aircraft out of harm’s way as much as possible, even repositioning them in the western reaches of the country, and instead employing its ground-based air defenses. These defenses are similarly made up of mainly Soviet-era legacy systems, which are extremely well known to Russia’s air forces, including Buks and older versions of the long-range S-300. But there are also MANPADS, including upgraded Igla and Strela types, which could pose a threat to low-flying aircraft, as could the more recently delivered U.S.-made Javelin missiles which have an anti-helicopter capability. Russia has also made major advances in the self-protection suites of its helicopters that could offset some of their effectiveness.

The weight of Russian numbers would almost certainly prevail, and Ukraine’s lack of strategic depth means its aircraft would still be vulnerable to missile strikes even when dispersed on the ground. However, the Ukrainian air defenses have the ability to at least slow down a Russian advance and, in the process, tie up the VKS in defense-suppression missions. There is also the possibility that Ukraine may receive more modern air-defense systems, too — although even if approved, they may not arrive in time, based on the more pessimistic timeline predictions.

Ultimately, Ukraine possesses a relatively tiny military force staring down a much larger one, and it has very little real means of counter-striking against Russian airpower facilities near the border. For Moscow, air superiority is likely assured, and Russia has shown that it is willing to accept combat losses during its campaign in Syria. Aside from the various manned air assets discussed here, Russia would likely make extensive use of lower-end drones for artillery spotting and for directing airstrikes, and loitering munitions are also now being employed, including in combat trials in Syria.

Whatever course a Russian intervention in Ukraine might take, there is little chance that it would not involve significant participation by the air assets of the WMD, SMD, and the wider VKS. Despite the gulf between the Russian and Ukrainian airpower in terms of numbers and modernity, Moscow’s defense planners will be well aware that a confrontation with the Ukrainian military would involve no shortage of hazards and that the control of the air will likely be crucial to developments on the ground.

Were there to be a new and large-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, Kyiv could perhaps try to impose enough attrition in the air over a long enough period for Moscow to rethink its actions. But the odds in the sky are very clearly weighted against Ukraine. As such, another strategy could be for Ukraine to forfeit air sovereignty over the war-torn eastern part of Ukraine and fortify everything to the west, especially around Kyiv, in preparation for what could be a long and arduous conflict.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com