Sikorsky has announced a whole family of vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) drones, all using a common tail-sitting design powered by twin proprotors. While the company has previously showcased and flight-tested this ‘rotor blown wing’ configuration, the new Nomad family includes increasingly large aircraft, all the way up to a size broadly equivalent to the S-70 Black Hawk medium-lift helicopter and intended for a variety of naval and land-based missions.

Military missions highlighted for the Nomad family include reconnaissance, light attack, and contested logistics. These reflect the Pentagon’s growing focus on runway independence, something that could be very advantageous in future operational contexts where traditional air base infrastructure may be destroyed, damaged, or otherwise unavailable.

“Nomad represents new breakthroughs for Sikorsky and the next generation of autonomous, long-endurance drones,” said Dan Shidler, director of Advanced Programs at the company. “We are acting on feedback from the Pentagon, adopting a rapid approach and creating a family of drones that can take off and land virtually anywhere and execute the mission — all autonomously and in the hands of soldiers, marines, sailors, and airmen.”

For each member of the Nomad family, the twin proprotor design combines the VTOL characteristics of a helicopter with the speed and range of a fixed-wing aircraft. The basic configuration includes a long straight wing with twin proprotors. The drone sits on its tail, supported by its tailfins, taking off and landing like a helicopter before transitioning to horizontal forward flight for long-endurance missions. The drone can also hover like a helicopter, making it suitable for missions like aerial firefighting and logistics resupply.

A rendering released by Sikorsky shows four different sizes of Nomad drone, although more iterations are possible. Different sizes will provide for a variety of speed, range, and payload capacity attributes.

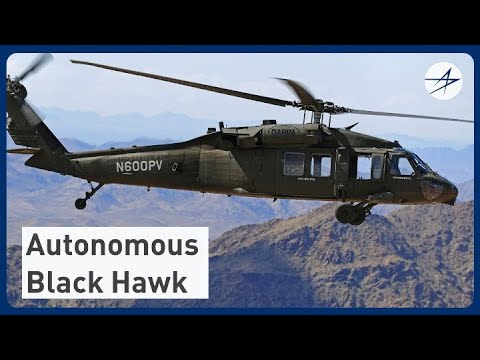

At the smaller end of the scale, the Nomad drones will mainly use hybrid electric propulsion, which is notably fuel-efficient, while larger variants will be powered by a conventional drivetrain. They will also make use of MATRIX autonomy technology, developed by Sikorsky and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). This has already been tested on a Black Hawk helicopter, as you can read more about here.

Currently the smallest, the Nomad 50 is already completing “extended” flight tests, as announced by the company earlier this year. This drone has a wingspan of 10.3 feet.

The company now says it’s building the larger Nomad 100, a Group 3 drone with an 18-foot wingspan. It’s now undergoing ground testing with the first flight expected “in the coming months.” Group 3 is defined as drones with a weight of 56 pounds to 1,320 pounds.

Next, a Group 4 drone is planned for the Nomad family, which should have a roughly 500-pound payload capacity. This would allow for larger sensors and larger weapons, such as a quartet of Hellfire missiles or a pair of Small Diameter Bombs (SDB), for example.

“We use the term ‘family’ to point to a key attribute of the design; its ability to be scaled in size from a small Group 3 UAS to the footprint equivalent of a Black Hawk helicopter,” said Rich Benton, Sikorsky vice president and general manager, in a company release. “The resulting Nomad family of drones will be adaptable, go-anywhere, runway-independent aircraft capable of land and sea-based missions across defense, national security, forestry, and civilian organizations. Nomads are a force multiplier, complementing the missions of aircraft such as the Black Hawk to retain the strategic advantage in the Indo-Pacific and across broader regions.”

Speaking to journalists, including TWZ, prior to the Nomad announcement, Benton said that most of the missions for the new drones are expected to be within Group 3 and Group 4. Of these, Group 4 encompasses drones weighing over 1,320 pounds, and operating at altitudes usually below 18,000 feet MSL.

Meanwhile, Ramsey Bentley, director of strategy and business development for Sikorsky Advanced Programs, explained the Group 3 Nomad in terms of U.S. Army applications, in which case such a drone would perform the same kind of missions as the RQ-7 Shadow, focused on brigade intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities. In the four-aircraft rendering, the three larger drones are all depicted with undernose sensor turrets for ISR and targeting.

The Group 4 Nomad would be more in the size category of the MQ-1C Gray Eagle, or with Gray Eagle-type capabilities, operated at the army, division, and corps level. Both aircraft would be ISR-focused but be capable of using kinetic and non-kinetic effects, as well as delivering cargo for contested logistics.

Contested logistics chains, in particular, are a major area of concern facing the entire U.S. military. Different branches are already actively looking at uncrewed aerial and other capabilities as ways to ensure forces, especially ones dispersed to far-flung locations to help reduce their vulnerability, can be adequately resupplied in the future. A drone like one of the Nomads would be particularly relevant for the large variety of smaller items that need to be moved around to meet logistical needs, especially when they are needed rapidly.

In a Sikorsky video, as well as the rendering at the top of this page, a Nomad drone is seen with an extensive array of externally mounted launched effects, and potentially other stores. Launched effects, previously referred to as air-launched effects (ALEs), describe a category of various uncrewed systems that you can read more about here. The launched effects terminology reflects the fact that they might be launched from land or maritime platforms, as well as crewed and uncrewed aircraft. Launched effects can carry a range of payloads, including kinetic warheads, but also active and passive surveillance equipment, decoys, and jammers.

Benton noted that he expects the Nomad drones to fly missions that can supplement traditional crewed helicopters, including Sikorsky’s own designs. At the same time, some missions previously assigned to crewed rotorcraft could be taken over by Nomad, in particular, ISR.

“You don’t necessarily need a crewed Black Hawk or a crewed Seahawk to do that mission,” Benton said. “Nomad’s going to do that. You still have the node on the network: There’s still a Black Hawk out there, there’s still a Seahawk out there, there’s still a CH-53K. It’s receiving the information, it’s translating. It’s connected sensor-to-shooter.”

In this way, Benton sees Nomad “as a way to augment or expand the kill chain or kill web by leveraging more resources to do the mission, instead of just the [crewed] aircraft. As we go forward, we’re evolving to provide the capability to do it affordably, at mass and efficiently, and I view it all as complementary, but the missions will change, and I think will shift between manned and unmanned as technology evolves.”

As a stepping-stone toward the new family of drones, Sikorsky has flown a smaller version, the aforementioned RBW-5 (for rotor blown wing), as a purely electric subscale demonstrator, now known as the Nomad 50.

This was one of the designs down-selected for DARPA’s AdvaNced airCraft Infrastructure-Less Launch And RecoverY (ANCILLARY) program, but then they put that on hold.

However, Sikorsky then joined DARPA’s EVADE program, in which it has been testing a 330-pound version of the same basic design, also a Group 3 drone, equivalent to the Nomad 100, with multiple aircraft now in various stages of flight test. With this program, Sikorsky progressed to a hybrid electric powerplant, including a diesel engine.

As for the forthcoming Group 4 Nomad drone, this is still on the Sikorsky drawing boards but has passed its preliminary design review. As yet, there’s no contract for it, but Igor Cherepinsky, director of Sikorsky Innovations, confirmed that the company is in discussions “with a couple of customers” and plans to build a demonstrator. Of the potential customers, at least one is civil, looking for a VTOL drone for cargo carriage in civil airspace.

Beyond these plans, Cherepinsky also raised the possibility of an even larger Nomad-type aircraft that could potentially carry passengers and/or larger cargoes. Were that to happen, the configuration would be changed so that the wing tilts, while the separate fuselage remains horizontal.

“As you may imagine, most of our passengers wouldn’t really like to be tipped 90 degrees,” Cherepinsky remarked. Otherwise, the tilting wing would retain the same basic control laws and physics as on the company’s tail-sitting designs. It is worth noting that the Pentagon is currently looking at new forms of combat search and rescue (CSAR) for more contested areas, including using forms of personal mobility technology. Some sort of Nomad-related design with the ability to carry passengers could also be relevant for these kinds of ambitions.

Sikorsky also says that the hybrid electric power trains used in the Nomad drones are also ideal for these kinds of environments, offering reduced sustainment requirements.

Bentley painted a picture of a future Nomad scenario in which the drone is operated by just two or three soldiers, who can launch it from a remote location, or a ship’s flight deck, sending it on its mission, via a tablet interface and without the need for a bulkier ground control station.

“Then, as the aircraft moves through the battlespace — in that air, ground, littoral that the Army talks about — they are able to be transferred to different operators,” Bentley explained. “So, the aircraft may launch from a brigade or operations area, but then it would fly forward and be utilized by multiple different operators within that brigade area, or even the division or corps area of operations. They don’t have to have the sustainment and support tail that you see in current UAS.”

In-field maintenance should also be eased by the Nomad’s significant degree of modularity, including, for example, the power module, which is “essentially a remove-and-replace kind of system,” Cherepinsky said. “The cost of it is pretty low. You can certainly refurbish them, but you don’t have to. By and large, it’s a pretty simple aircraft with very few avionics boxes.”

Overall, with its focus on operations in austere environments and ability to take off and land from warships and other confined spaces, the Nomad family is clearly oriented toward the Pentagon’s drive for increasing runway independence, especially in the Indo-Pacific theater.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com