As the U.S. military’s primary focus shifts to potential high-end conflicts with adversaries such as Russia and China, senior U.S. Air Force leaders are warning that the service must be prepared to deploy to a region and quickly set up new bases. Otherwise, the service risks seeing its operations hampered, if not brought to a halt entirely for at least some amount of time, if an enemy has destroyed or otherwise render established facilities unusable in the opening stages of a major war.

At the Air Force Association’s annual Air, Space, and Cyber conference on Sept. 18, 2018, U.S. Air Force Chief of Staff General David Goldfein announced plans to have many of the service’s major regional and functional commands work together to update and expand doctrine and concepts of operation for these possible expeditionary missions. The service had debuted a set of expeditionary concepts in 1998, building on lessons learned from previous rapidly deployment concepts, but has not significantly updated them in the decades that followed.

“Over time, we’ve migrated away from the original design of the expeditionary Air Force from a force organized to deploy forward, establish new bases, defend those bases, receive follow-on forces, establish C2 [command and control], fight the base, and operate while under attack – to a force that often cannibalizes itself to send forward sometimes individual airmen from every wing of the Air Force to join a mature campaign with established leadership, basing, and C2 infrastructure,” Goldfein explained. “Make no mistake: From Bagram[ Airfield in Afghanistan] to Al Udeid [Air Base in Qatar], to Kunsan and Osan [Air Bases in South Korea], we know how to defend an establish base, receive follow-on forces, and take the fight to the enemy,”

The problem is that American’s potential high-end opponents are only continuing to improve and diversify their capabilities to hold these types of established sites at risk or deny access to areas with those facilities that are closer to the front lines. China, in particular, is expanding the size and scope of its ballistic missile arsenal. Russia and China are now pushing ahead with various types of hypersonic weapons, which will only expand their options for rapidly attacking operational bases, as well.

It is virtually assured that many American bases, or bases to which the Air Force has access, will find themselves under a massive missile barrage at the beginning of a major, all-out high-intensity conflict. Any known secondary dispersal sites and “bare bases,” which may have an existing runway, but little else, will be similarly vulnerable. So, it may not just be prudent for the Air Force to have a plan to fight without the benefit of these facilities, it may be a vital necessity, Goldfein said.

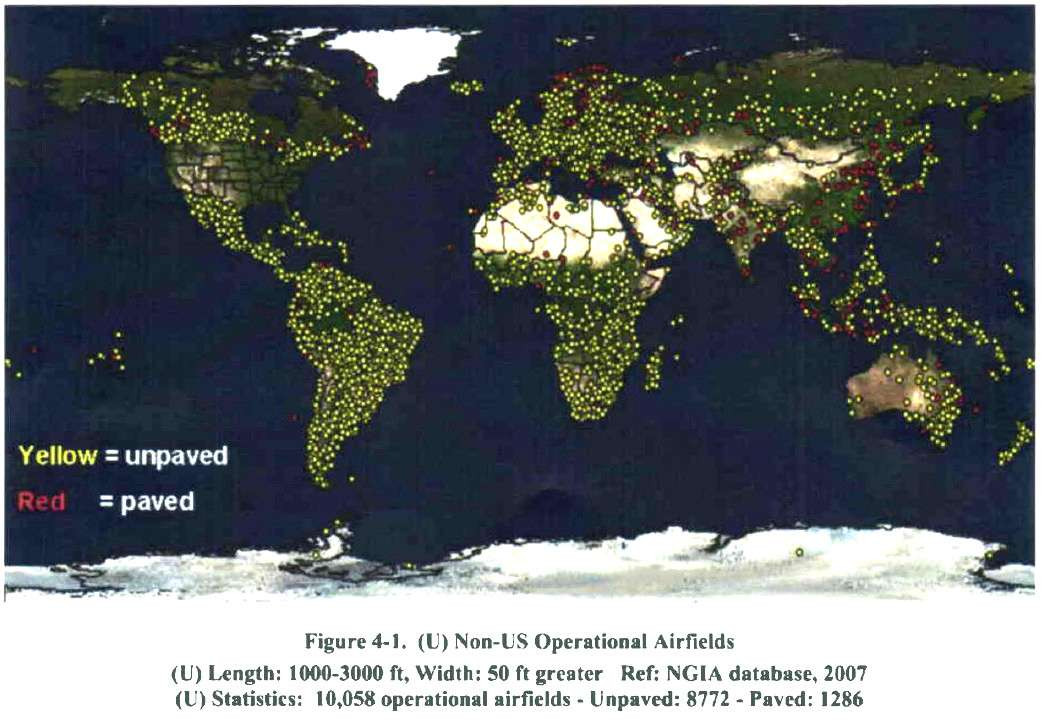

The ability to conduct expeditionary, distributed operations has inherent benefits, as well. An opponent will only have so many missiles and other long-range weapons with which to target the bases and possible bases that it knows about. Being able to rapidly establish functioning airfields in austere locations could force an enemy them to spread their resources thinly across a larger number of objectives or create surprise vectors of attack that simply disrupt their operational planning.

Goldfein offered few specific details about how the Air Force might reorganize itself or otherwise change its posture to be better suited to deploying to an area with very limited, if any, established airbase facilities and possibly having to build them up, under fire, from scratch. The service’s top officer did focus heavily on the need to improve expeditionary base defense capabilities, but there would also need to be significantly increased the attention given to civil engineering and Rapid Engineer Deployable Heavy Operational Repair Squadron Engineers (RED HORSE) units, explosive ordnance disposal personnel, rapidly deployable air traffic control systems, and other, often neglected ground support functions.

“We must always take integrated and layered base defense to a new level by increasing investment in our defenders with new equipment, new training, new tactics, techniques, and procedures, and renewed focus at every echelon of command,” Goldfein said. “This is the year of the defender because we don’t project power without the network of bases and infrastructure needed to execute multi-domain operations.”

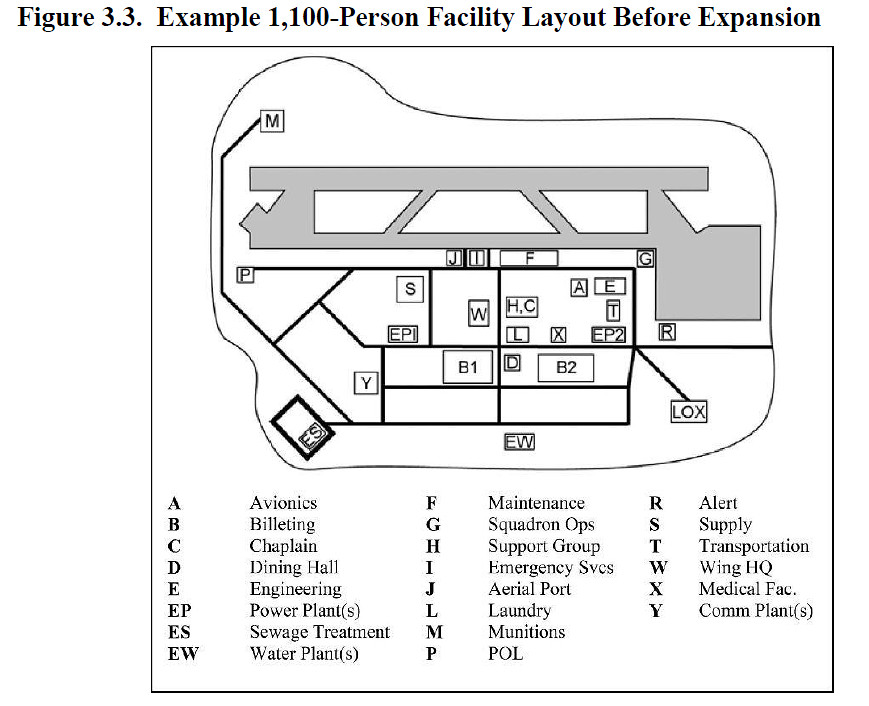

The Air Force won’t need to start from scratch, though. The service will be able to pull some amount of pre-existing knowledge from the concepts it developed in the late 1990s. The manuals for bare base operations, for instance, remain available and some even got minor updates in the early 2010s.

In addition, both Air Combat Command (ACC) and Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC) have experimented with various rapid deployment concepts, including one known as “Rapid Raptor.” This force package typically includes four F-22 Raptor stealth fighters and a C-17A Globemaster III cargo plane with everything necessary to support those aircrafts’ operations for at least 24 hours. The Air Force has more recently been working to find a way to get all of the necessary equipment into a C-130 airlifter, or a specialized HC-130 or MC-130 type.

AFSOC also has considerable experience in readily identifying potential improvised landing strips that can serve as limited, temporary bases of operations. For example, in 2013, what are known as Assault Zone Reconnaissance Teams conducted site surveys and other inspections at almost 300 separate sites throughout the Middle East to help support existing and future operations.

This information almost certainly came in handy when the U.S. military rapidly established a series of airfields inside Syria starting in 2016 – if not before – to support the campaign against ISIS terrorists. Both special operations and conventional Air Force units have employed similar rapid deployment concepts throughout Africa. This included an instance where the 3rd Special Operations Squadron established an unmanned aircraft operation with one MQ-1 Predator at an undisclosed location within three weeks.

Translating this existing experience to modern operations involving fifth-generation aircraft and ever-improving enemy air defenses, combat aircraft, and other threats, won’t necessarily be easy. The logistical demands of operating and maintaining advanced fighter jets, even from established bases, are only likely to increase as time goes on.

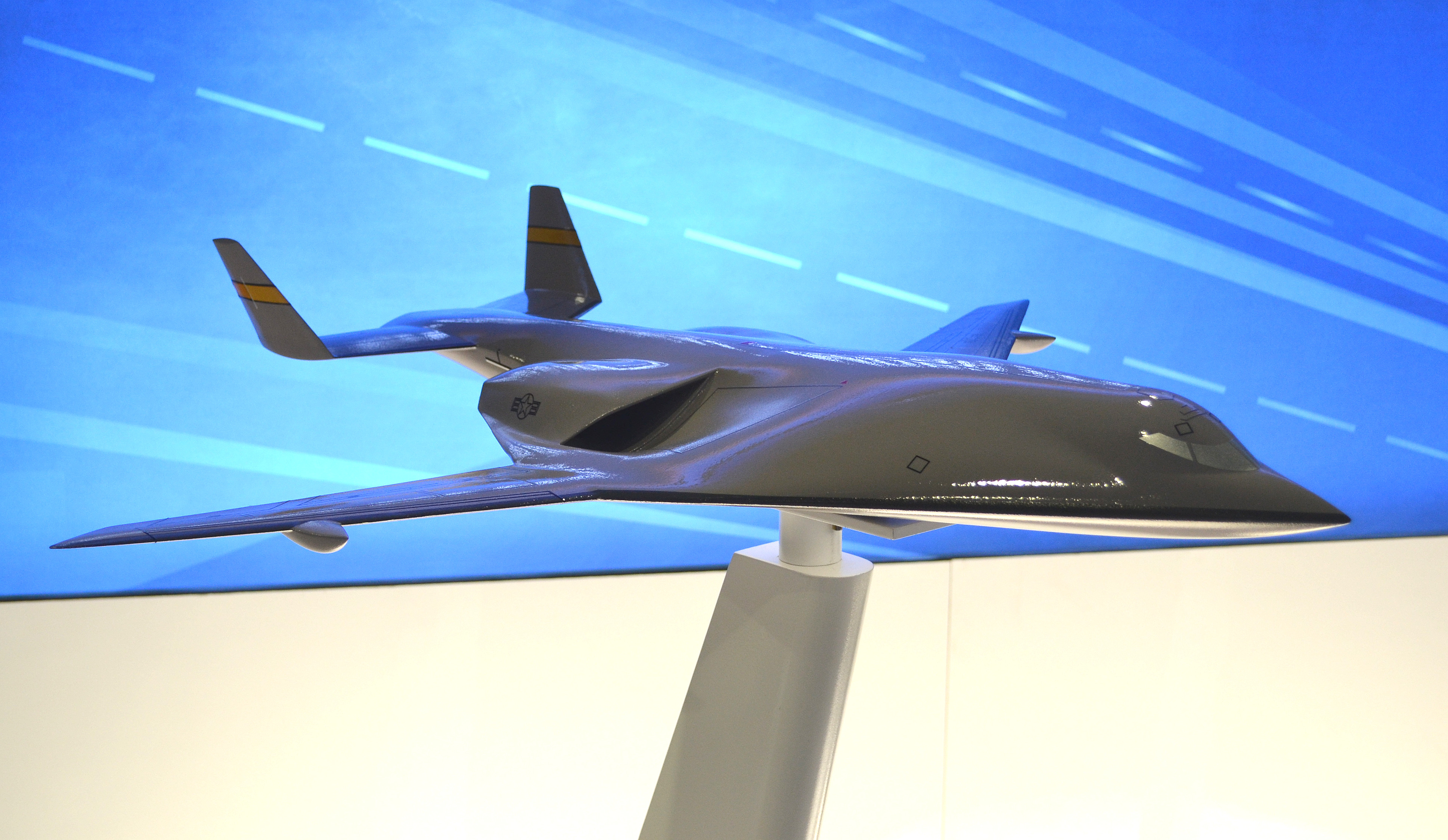

These difficulties are especially pronounced for stealthy types, which will be critical in the opening phases of an operation to help penetrate through enemy defenses and clear the way for follow-on strikes and deployments. These types of aircraft, such as the F-22 and F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, have complex sustainment and maintenance requirements due to their low observable features that might be difficult to perform at a remote location, especially if forces find themselves cut off even briefly from their supply lines. It looks increasingly likely that the Air Force may need stealthy or otherwise better protected

aerial tankers and cargo aircraft just to get forces to some of these locations safely in the first place.

Not all aircraft are as suitable for operations from unimproved or improvised runways, either. The Air Force’s A-10 Warthogs have the ability to use highways as impromptu air bases if necessary, and their crews train to do so, but this isn’t an option for more advanced combat jets such as its F-35As. The service could have to revise its inventory in addition to its force structure to be best prepared for uncertain expeditionary operations in the future.

The Air Force could find itself considering obtaining capability similar to the U.S. Marine Corps’ F-35B, if not that exact aircraft, which has the ability to conduct short and vertical takeoffs and landings. The Marines have already demonstrated that these planes can operate from relatively short concrete pads.

With this in mind, it’s also important to note that the Air Force won’t be conducting these sorts of expeditionary operations independent of the other services. The battlefield construction, logistical, and other relevant capabilities that the Army and Navy possess will be essential, as will the ability to tap into a robust, overarching set of communications and intelligence-sharing networks to keep appraised of the situation and coordinate continued support at austere facilities. Training forces to operate as joint units that blend the necessary components for these types of missions will be key.

In addition, U.S. Air Force Lieutenant General Mark Kelly, head of 12th Air Force, which is part of ACC, warned at the 2018 Air Force Association conference in September 2018 that forces are likely to be in danger of kinetic and non-kinetic hazards even when mobilizing or transiting to a theater of operations. “No one opposes airmen driving to BWI [Baltimore-Washington International Airport],” he said.

“No one is in the computer systems tracking their luggage. No one is in [Air Mobility Command’s] computer systems that keep the equipment flowing forward,” he continued. “But if great powers can get into your election networks, then trust me, they can get into your baggage handlers.”

Cyber attacks and other traditional electronic warfare will also threaten personnel once they arrive at a certain location, too. In September 2017, a group of A-10s from the Maryland Air National Guard’s 175th Wing practiced operating from a highway in Estonia, a NATO member that sits along the Baltic Sea and shares a major border with Russia. The exercise included a simulated cyber attack on the unit’s forward operations center by Estonian military personnel and British civilians playing the role of “politically motivated hackers.”

That exercise, nicknamed Baltic Jungle, showcased just a small number of the capabilities Goldfein and Kelly are now saying it is vital for the Air Force to have in greater quantities. It also reflected a tiny portion of the sorts of multi-faceted threats that U.S. forces might face during future operations.

Still, the lessons learned from this drill, and other recent ones similar to it, will likely serve as important stepping stones as the Air Force looks to reinvigorate its expeditionary capabilities in the coming years.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com