The U.S. Army has released a detailed look at what it wants from a new family of air-launched multi-purpose unmanned aircraft, which will include types capable of operating as scouts, electronic attackers, decoys, and even suicide drones. They will be capable of semi-autonomous operating together with other manned or unmanned planes and helicopters and may be able to work together by themselves as a fully-autonomous, networked swarm. These so-called “Air Launch Effects” are set to be a key component of the arsenal for the Army’s future advanced armed scout and assault transport helicopters, but will also almost certainly find their way onto other existing and future manned and unmanned platforms, including the service’s MQ-1C Gray Eagle drones.

The Army’s Combat Capabilities Development Command (CCDC) released a request for information for possible drones and associated technologies that could into various types of these Air Launch Effects (ALE) on Aug. 12, 2020. The contracting notice is focused primarily on prospective drones that fit into “large” and “small” size categories and systems to enable them to perform one or more of four different functions, active and passive surveillance types, decoys, and those capable of “disrupting” the enemy via non-kinetic strikes. There is also a mention of an “ALE-Lethal,” a loitering munition type, though the specific desired capabilities for it are not outlined in the document.

“The future multi-domain operational environment will present a highly lethal and complex set of traditional and non-traditional targets,” the contracting document says by way of introduction. “These targets will include networked and mobile air defense systems with extended ranges, and long and mid-range fires systems that will deny freedom of maneuver.”

As part of a larger “ecosystem” to defeat these threats, there is a need for “a family of small and large unmanned air launched systems that operate as members of a team with other manned and unmanned platforms to detect, identify, locate, report (DILR) and deliver lethal and non-lethal effects against threats,” it continues.

As it stands now, the Army says that the large ALE category will consist of drones weighing no more than 225 pounds, and hopefully less than 175 pounds. The service wants them to, at a minimum, be able to fly at speeds of at least 70 knots with a combat range of up to 350 kilometers and a total flight time of 30 minutes. The goal is to be able to push those performance specifications to up to 650 kilometers and an hour of total time in the air.

The small category will include drones under 100 pounds, and possibly no more than 50 pounds, in the end, that can cruise at 30 knots over a distance of 100 kilometers and have a total flying time of at least 30 minutes. The objective performance for these smaller ALEs is a 150-kilometer range and an hour of flight time.

The Army also wants both types to have much higher “dash” speeds to allow them to rapidly get to a particular area or relocate from one to another. The service says that the large ones should able to hit at 350 knots for short sprints, and maybe even go as fast as 600 knots, while the smaller ones would need to get up to at least 120 knots, with a goal of a maximum speed of 205 knots. The service says it is willing to explore proposals involving any type of propulsion system, including combustion or jet engines or electric power.

The plan is for both categories of ALEs to be able to perform at least one of any of the core outlined missions. This includes reconnaissance and targeting missions that the Army is referring to here as “detect, identify, locate, report,” or DILR.

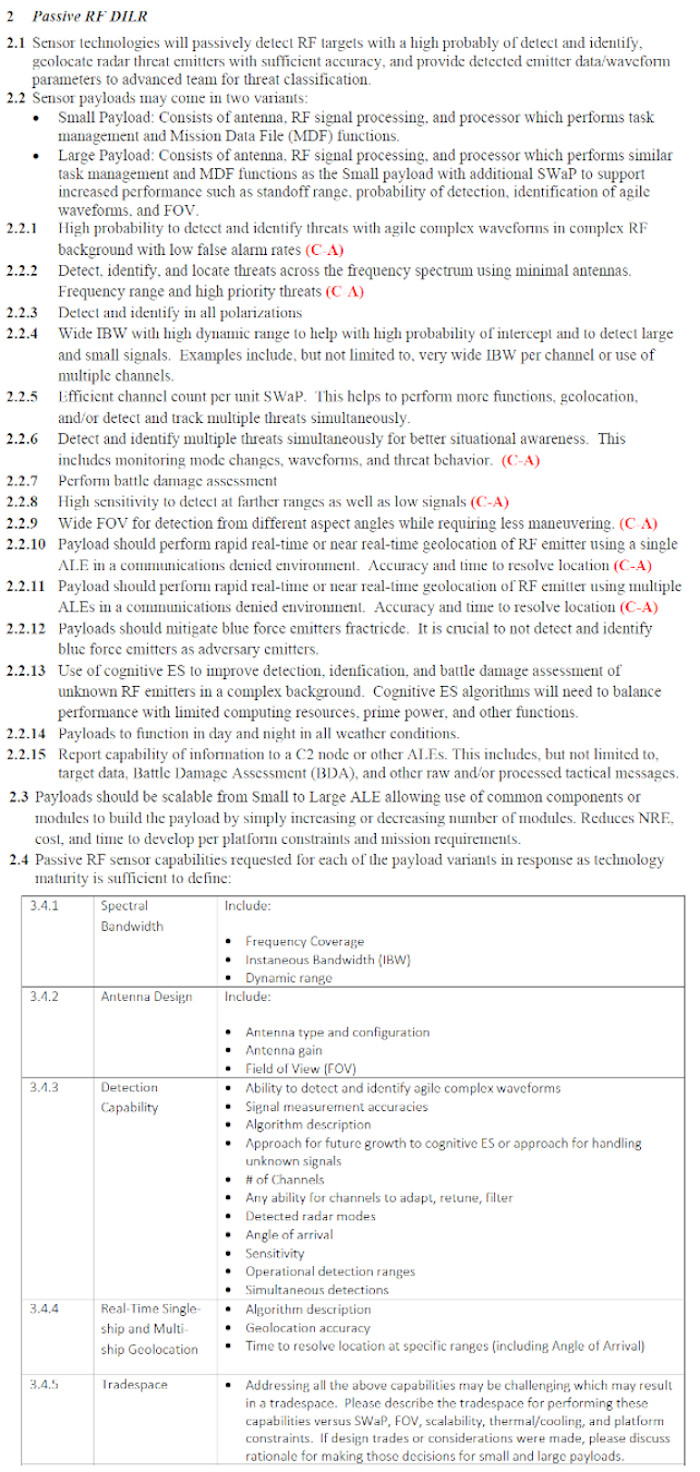

DILR ALEs will themselves fall into at least one of two categories, passive. The payloads on the passive types could include electro-optical or infrared imaging camera or sensors to detect and geolocate an opponent’s electromagnetic emissions from their communications systems, radars, or other signal emitters.

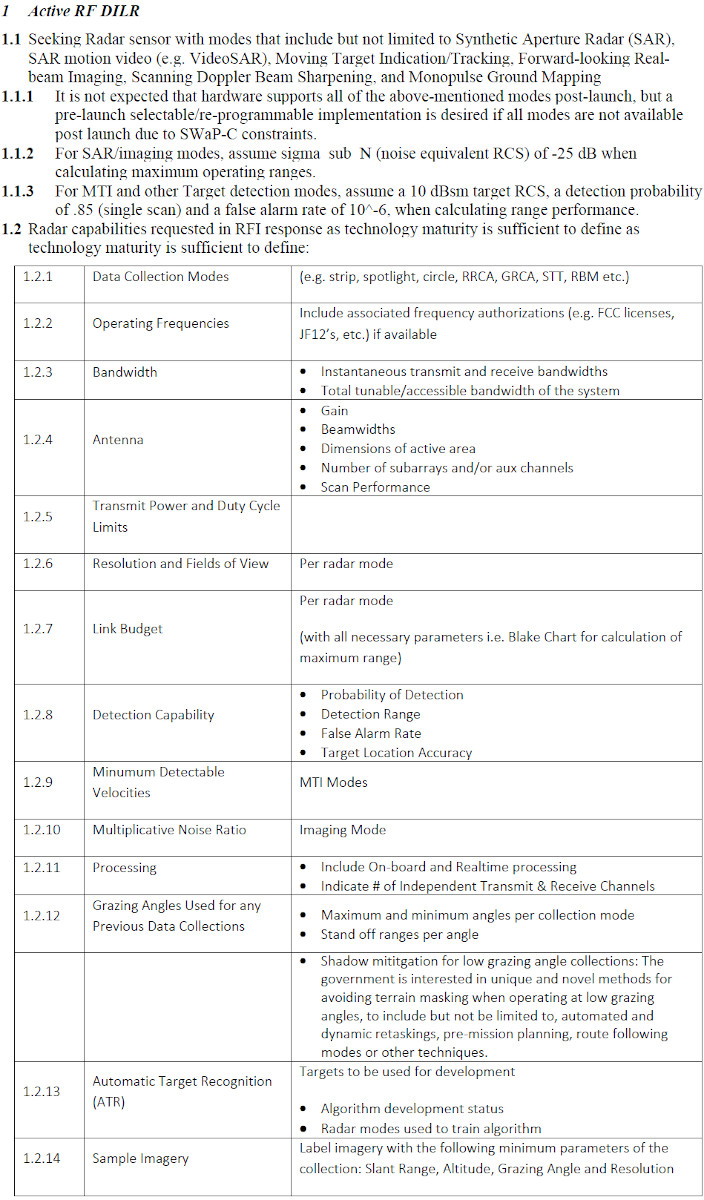

The active DILR types would be equipped with radar imaging systems capable of producing still images and full-motion video, as well as tracking moving targets. These would also have a ground mapping capability.

A network of robust, jam-resistant, low probability of intercept/low probability of detection (LPI/LPD) datalinks on the ALEs themselves would allow them to send any of that information to other platforms operating the area or to rear command posts for further exploitation or just to give commanders increased situational awareness. This would also include locational information for targeting purposes using stand-off munitions.

The contracting notice also says specifically that the camera systems on the passive DILR drones would also be paired with artificial intelligence-driven machine learning algorithms to automatically identify potential targets of interest. The electronic signal-sensing suites would be able to gather a significant amount of information about the emissions they might detect to assist personnel elsewhere in classifying them.

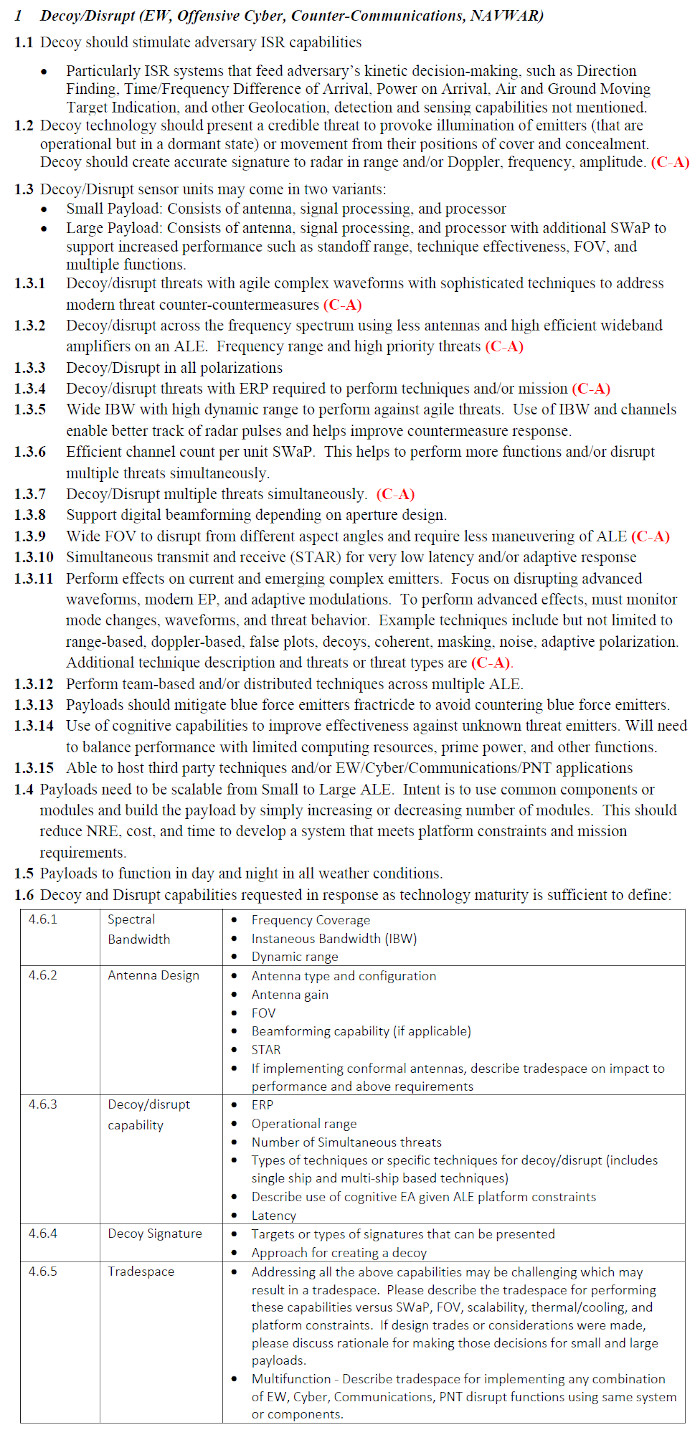

The Army’s ALE request for information lumps a wide array of electronic mission sets in a broad category described as “decoy/disrupt.” This includes systems that would enable the drones to act as decoys to confuse enemy air defenses, as well as launch a variety of electronic warfare, cyber warfare, and navigation warfare attacks. The latter category includes jamming and spoofing signals from space-based systems responsible for navigation, weapon guidance, and other related functions, such as the U.S. GPS satellite constellation or Russia’s GLONASS.

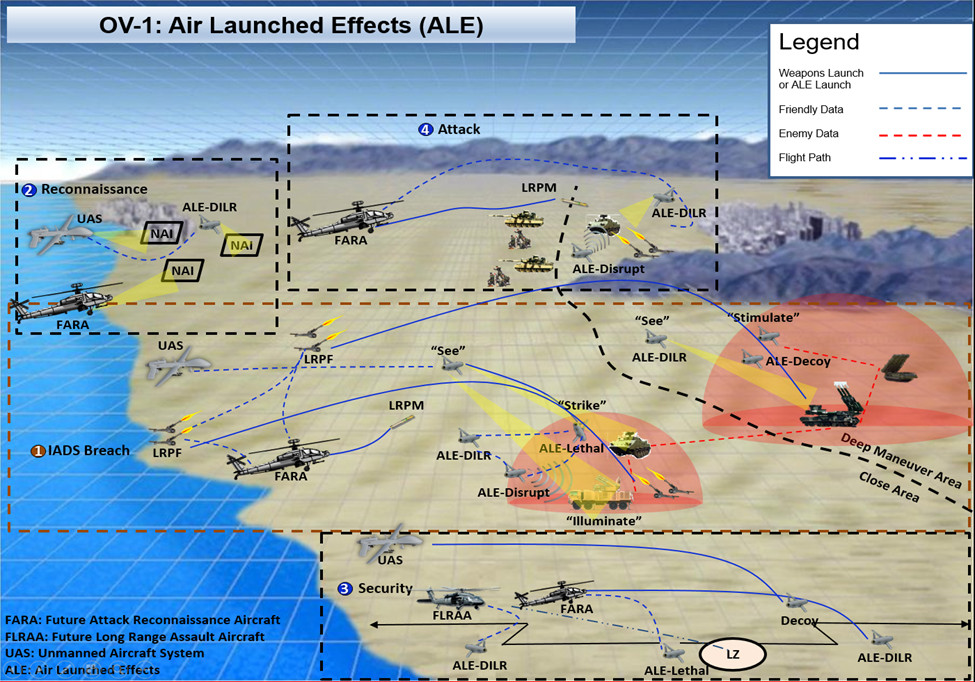

A graphic included in the Army’s contracting notice, seen at the top of this piece, which depicts a battlefield full of different types ALEs, makes it clear that the service envisions drones with different payloads working as part of a larger team. The scout and disruption types could easily work together to locate and neutralize threats through non-kinetic attacks. The ALE-Lethals, which could contain a kinetic warhead, could also swoop down to strike those targets.

Larger manned and unmanned aircraft, as well as warships and ground-based stand-off weapons, including future hypersonic missiles, could also use the information provided by the ALEs to prosecute strikes against an opponent’s integrated defense and command and control networks. Swarms of ALEs operating autonomous or semi-autonomously could also seek to push into higher-risk areas to find time-sensitive or otherwise high-priority targets.

All told, a swarm of these air-launched drones blind and confuse enemy air defenses, scramble communications links, and otherwise upend an enemy’s defensive posture and drawing their attention away from actual friendly forces. It is possible that they could be integrated, at least to some degree, with similar networked assets that are in development elsewhere across the U.S. military. In fact, the decoy and disruption ALEs sound very similar in general concept to what the Navy is working on with its shadowy Netted Emulation of Multi-Element Signature against Integrated Sensors, or NEMESIS, program, which you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone piece.

In addition, while the Army has not yet decided on what drones it might acquire to fulfill any of its ALE requirements, this request for information follows tests involving the air-launching of Area-I’s small Air-Launched, Tube-Integrated, Unmanned System 600 (ALTIUS 600) drones from the service’s MQ-1C unmanned aircraft and UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters in the past year or so.

With a maximum overall weight of fewer than 30 pounds, the ALTIUS 600 is smaller than what the Army says it is looking for even for the smaller ALE drone, but fits a broad description of the kind of system the service wants. The ALTIUS can be fired from a Common Launch Tube (CLT) and carry various types of payloads weight between three and seven pounds, including full-motion video cameras, small signals intelligence systems, or even a kinetic warhead.

Bell has actually used drones that look very much, if not identical like the ALTIUS 600 in computer-generated videos promoting its Invictus armed scout helicopter. Invictus is now competing with Sikorsky’s Raider X under the Army’s Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft (FARA) program.

FARA, intended to supplant the AH-64 Apache attack helicopter in the armed scout role, is part of an overarching effort to develop a family of new rotary-wing aircraft to replace the service’s existing helicopter fleets, known as the Future Vertical Lift (FVL) program. The ALEs will be a primarily store for the final FARA design, as well as that of the Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA), which is set to supplant at least a portion of the service’s Black Hawks. As is indicated by the tests of the ALTIUS 600 and the graphic in the ALE request for information, the Army is also interested in integrating this new family of small drones onto the MQ-1C or other future unmanned designs, as well.

Of course, it remains to be seen how the ALE effort, as well as work on FARA, FLRAA, and other possible launch platforms, may continue to evolve as the Army refines its requirements and gets feedback on what potential contractors thing is viable. The service says it plans to hold an industry day gathering on ALE next month to facility exactly those kinds of discussions.

Still, the Army clearly sees a future wherein its manned and unmanned aircraft fleets will be able to launch swarms of drones that will begin searching out enemy forces, disrupting their operations, providing targeting information for other friendly units, and launching both kinetic and non-kinetic attacks themselves.

Author’s note: A slide regarding the ALTIUS 600 that originally appeared in this article has been removed at the request of Area-I.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com