In a conflict with China, which would require the U.S. military to operate over vast swaths of ocean, ports, other logistical hubs, and command and control centers would be especially vulnerable, the top Marine says.

“I think logistics in a contested environment is a huge challenge for us,” Marine Corps Commandant Gen. David Berger said last week during a conversation with the Hudson Institute. “Not insurmountable, but we need to acknowledge that we should assume…they’re going to challenge our sustainment. We have work to do.”

That work, he said, requires a “real relook at everything from pre-positioning ashore to pre-positioning afloat to the lift that conventionally has gone across the ocean through this solid protected pipeline delivered in some big port.”

But that was then.

“That’s not how we’re going to need to think about it going forward, because I think realistically they’re going to challenge us back in our port or beyond,” he said. “They’re going to try to slow our mobilization. They’re going to do everything that they can to slow us down as far back as possible. Sustainment is a huge challenge.”

But logistics nodes won’t be the only target, Berger said.

“We should assume that on both sides we’re going to try to go after soft spots early on. You would go after command and control because you would think they rely on it so much that if I can just interdict that, if I can hurt their command and control, we can start to have a more of a fair fight.”

Among other things, Berger’s plan for the future of the Marine Corps, the Marine Force Design 2030 initiative, anticipates a stand-in force of forward-based Marines deployed inside the range of Chinese fires. The idea is to pre-position troops and supplies not just in case of a conflict but to make China think twice about any attacks because there are forces already forward. In essence, there would not have to be a prolonged logistical response in order to engage in combat, the force is already there, in China’s backyard.

The Force Design 2030 initiative, officially launched on March 23, 2020, aims to fundamentally change the way Marines operate after 20 years of land-focused warfare in Afghanistan and Iraq.

It calls for addressing what Berger says are shortfalls in a variety of increasingly important capabilities, including expeditionary long-range precision fires; medium to long-range air defense systems; short-range (point defense) air defense systems; high-endurance, long-range unmanned systems with intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, electronic warfare, and lethal strike capabilities. In addition, the initiative seeks “disruptive and less-lethal capabilities appropriate for countering malign activity by actors pursuing maritime ‘gray zone’ strategies.”

The concept is to redesign the force to focus once again on naval expeditionary warfare “and to better align itself with the National Defense Strategy, in particular, its focus on strategically competing with China and Russia,” according to a 2021 Congressional Research Service report. This includes a focus on distributed operations, including smaller teams of Marines with advanced weaponry spread across large swathes of territory, not on centralized beach landings as the force has invested in and prepared for over the decades.

Given the paucity of sealift and associated Navy escort vessels, the ability to keep U.S. forces supplied at long distances into contested waters is a long-standing concern, an issue we have examined in detail. The Military Sealift Command’s fleet remains a potential weak spot in America’s naval strategy if the country had to sustain a conflict with a peer state adversary. You can read more about this issue here, here, here, and here.

In his most recent update to the Force Design plan, Berger back in May addressed concerns about logistics

“To persist inside an adversary’s weapons engagement zone, our Stand-in Forces must be set and sustained by logistics capabilities designed for distributed operations over long distances in a contested environment,” he wrote.

This will require a mix of vessels, from what was called the Light Amphibious Warship, to smaller craft, to “a mix of vessels that are complementary to, but different from amphibious warships.”

In addition, he is calling for the establishment of 18 multifunctional combat logistics battalions, two distribution support battalions, and two material readiness battalions.

Looking toward the future, Berger wrote that “our next set of uncrewed capabilities will focus on logistics, manned/unmanned teaming, and higher-end tactical systems.”

That approach “will be informed by the significant experimentation and prototyping that has already begun, and as reflected in our recently drafted Uncrewed Roadmap.”

There are several such capabilities being discussed by the military. One is the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA Sea Train program, which aims to demonstrate long-range deployment capabilities for a distributed fleet of tactical unmanned surface vessels.

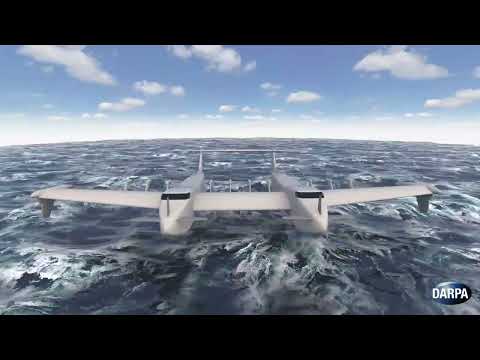

Another is the DARPA Liberty Lifter, a flying transport that is able to operate from water and employs the ekranoplan, or wing-in-ground (WIG) effect principle.

The good news, Berger told The Hudson Institute, is that “we have creative people thinking about it, trying different approaches” to long-distance supply.

One of those approaches is working with allies and partners in the region who can help provide supplies in a time of crisis.

“Some people think of allies and partners in terms of ‘who’s going to fight alongside of you?'” he asked rhetorically. “I think in terms of ‘yes, also, this is the pantry. This is the store you’re going to buy your goods from.’ And it’s all around you. If you just open up your mind a little bit, it doesn’t all need to come from the East Coast or the West Coast of the U.S. [That’s] the value of allies and partners, if we can get it.”

Berger’s comments came against the backdrop of the biennial Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC), the world’s largest international maritime exercise which kicked off June 29 and runs through Aug. 4.

This year’s exercise program includes gunnery, missile, anti-submarine and air defense exercises, as well as amphibious, counter-piracy, mine clearance, explosive ordnance disposal, and diving and salvage operations. RIMPAC 22 is also introducing space and cyber operations for all partner nations.

“By coming together as capable, adaptive partners, and in the scale that we are, we are making a statement about our commitment to work together, to foster and sustain those relationships that are critical to ensuring the safety of the sea lanes and the security of the world’s interconnected oceans,” said RIMPAC 2022 Commander, Vice Admiral Michael Boyle.

“This is also how we find the areas where our national objectives overlap,” said Boyle, “where we can practice the procedures that will help to enable our interchangeability –the nexus of national will and interoperability.”

But partners aside, Berger said ensuring Marines inside the Chinese weapons engagement zone are sustained and supplied means creating “a distributed framework of keeping things operational forward and sustainment of supplies forward.”

There is work to do there as well.

“But I’m optimistic because the right people are starting to think through and experiment with how we’ll do that,” Berger said.

“The most forward parts of the U.S. military in a contested environment before shots are fired, are going to be special operations units, submarines and Marines,” he said. “So the first step is if those three are forward persistently 24-seven, how do we stitch them together into some sort of framework where they can move information, where they can move supplies, where they can with some overlap but not too much redundancy and cover the playing field?”

That, he said, “is a place we haven’t been in in a while to stitch together that tightly. We can. We should. And in the last six months, [we’ve been] going 100 miles an hour to sort through how to do that.”

Contact the author: howard@thewarzone.com