The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is looking to explore concepts for a new drone capable of lugging around up to 70,000 pounds (or 35 tons) of cargo, roughly twice what the U.S. Marine Corps’ CH-53K King Stallion helicopter can lift. Unlike the CH-53K, the new uncrewed aircraft would be a shorter-range platform focused primarily on moving outsized payloads between ships and beachheads ashore, as well as across wide rivers and other similar ‘gaps’ inland.

DARPA’s Tactical Technology Office (TTO) recently put out a call for information about “innovative and revolutionary concepts for heavy lift Uncrewed Aerial Systems (UAS) that are capable of lifting a 70,000lb payload utilizing current Commercial Off The Shelf (COTS) engines and drive train technology” as part of what it has dubbed the Cost Efficient Cargo project. The contracting notice explicitly notes that “the Sikorsky CH-53K King Stallion is currently the American [military] helicopter with the highest payload capacity at 36,000lbs.”

The notice further outlines a notional mission profile for a future Cost Efficient Cargo drone wherein it would “fly from a prepared base to the payload location [and] attach/obtain 70,000lb payload, traverse 25mi at 500ft, detach payload, [and then] return to base 25mi [away].”

Beyond a desire for the drone to use a high degree of COTS components, the stated design requirements are very open-ended. DARPA’s contracting notice indicates a willingness to consider uncrewed aircraft powered by traditional fuel-burning engines or electronic motors, or a hybrid combination of both.

The projected mission profile and the comparison to the CH-53K, as a mention of “rotors” also point to an interest in vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) capable platforms. However, DARPA does not explicitly say this is a hard requirement.

“Autonomous functions are expected but not the focus of this RFI [request for information],” the contracting notice says.

“Additionally, DARPA is interested in identification of design insights and key risks that can be addressed within a scaled down form to further substantiate DoD investment in heavy lift systems and challenge the paradigm of current UAS design as a whole,” the Cost Efficient Cargo notice adds. A range of potential scaled payload capacities (10,000, 30,000, and 45,000 pounds) and ranges (10, 25, 50, and 100 miles) that are of interest are provided.

“The bottom line is that the U.S. needs to move large and heavy cargo cheaply. Examples are moving a 40ft ISO container off a container ship 10 miles out at sea onto land, or a Bradley fighting vehicle from one side of a canyon to the other,” according to DARPA. “There are significant challenges in amphibious operations and land maneuvers, where armed forces must move troops, vehicles, and supplies from naval vessels to a beachhead and then across natural or man-made obstacles.”

“These operations are complicated by the need for landing craft and amphibious vehicles to navigate shallow waters, avoid obstacles, and contend with enemy defenses. The speed of movement is a critical operational need; any delays in offloading personnel and equipment during both the ship to shore phase and on shore wide gap crossings can expose forces to enemy fire and hinder the establishment of a secure foothold,” the contracting notice adds. “Additionally, weather and sea conditions can severely impact the safety and efficiency of landings, while enemy defenses, including mines, artillery, and entrenched infantry, pose significant risks.”

“Once a foothold is secured, forces often encounter wide gaps, such as rivers, ravines, or destroyed bridges, that hinder the movement of heavy equipment,” it continues. “These obstacles require engineering solutions such as pontoon bridges or amphibious vehicles, but such operations are time-consuming, giving the enemy time to prepare.”

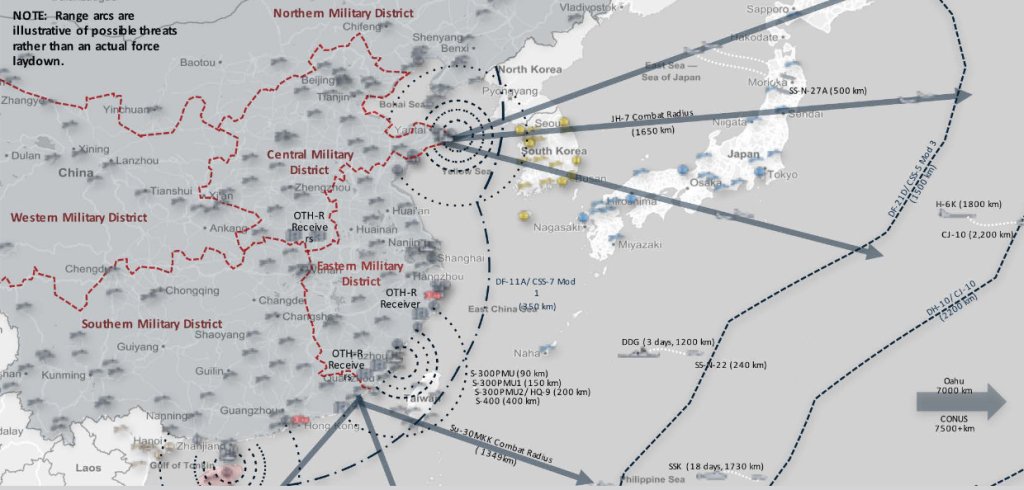

Concerns about ever-growing challenges in getting cargo from ships to shore, especially in higher-end conflict scenarios against opponents like China with substantial anti-access and area denial capabilities, are hardly new. Ever-more-capable anti-ship cruise missiles have been cited particularly often as a significant threat to amphibious warfare ships that will only increasingly limit how close they can get to shore. Launching forces, either in landing craft or amphibious vehicles, from further out to sea puts them at greater risk, as well.

Even once a beachhead is established, friendly forces would still have to contend with a variety of threats. The U.S. military’s recent experience operating a temporary pier to try to help get additional humanitarian aid into the Gaza Strip underscores how weather and other environmental factors can present additional serious issues for amphibious operations.

As DARPA’s Cost Efficient Cargo contracting notice highlights, gap-crossing operations inland across rivers and other obstacles, natural and man-made, face many of the same kinds of challenges. The ongoing war in Ukraine has underscored these realities, especially when it comes to the employment of temporary combat-bridging capabilities. The steady proliferation of longer-range precision-guided munitions and near-real-time intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities only increases the vulnerability of static crossing points.

At the same time, there are questions about how effective and efficient a fleet of future heavy-lift drones, especially ones with limited range, might be in addressing the aforementioned issues. While a payload capacity of up to 70,000 pounds is substantial, so are the weights of the kinds of cargoes that DARPA envisions the Cost Efficient Cargo platform moving. For instance, the recent contracting notice specifically mentions the Bradley Fighting Vehicle. The typical weight of the latest M2A4 version of the Bradley with a full combat load is 80,000 pounds, according to manufacturer BAE Systems.

A need for more drones flying more sorties to meet the desired mission demand could negatively impact the cost-effectiveness equation even if the underlying Cost Efficient Cargo system is relatively cheap to acquire and operate. It is worth noting that the same kinds of cost calculations already apply to crewed platforms. With a current unit price of around $118 million, the CH-53K is a notably expensive aircraft.

The U.S. military does increasingly see drones carrying cargo and potentially personnel as key to meeting logistical requirements, especially in major conflicts, such as one against China in the Pacific. The U.S. Marine Corps, which has been completely restructuring itself around new expeditionary and distributed concepts operations in recent years, is pushing to acquire three different tiers of VTOL cargo drones.

The Kaman KARGO drone depicted in the video below is one of the designs the Marine Corps is currently considering acquiring.

The U.S. Army and U.S. Air Force, which expect to see their forces widely dispersed in future high-end fights, are also exploring VTOL (like the Piasecki ARES seen in the video below) and fixed-wing uncrewed aircraft to support logistics missions. However, none of the platforms U.S. military services are pursuing now have anywhere near the payload-carrying capacity DARPA is looking at for Cost Efficient Cargo.

As The War Zone has highlighted in the past, the U.S. military is also increasingly lagging behind China in its development of uncrewed aerial logistics capabilities, especially when it comes to fixed-wing cargo-carrying drones. Two new Chinese cargo-carrying drones, one from ostensibly private firm Tengden and another from the state-run Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC), separately made their first flights just earlier this year.

How any heavy lift drones that come out of the Cost Efficient Cargo project might fit into the U.S. military’s future air mobility ecosystem remains to be seen, but DARPA’s new project reflects real operational demands and growing challenges in meeting them.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com