The boss of U.S. Strategic Command, Admiral Charles A. Richard, has told Senators that if the U.S. scraps its intercontinental ballistic missiles, he would recommend that Air Force bombers go back on nuclear alert duty. The disclosure came during a testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee today in which Richard also specifically warned about the risk that adversaries might see nuclear weapons as their “least bad option” in future conflicts.

While the Biden administration has indicated that it seeks to retain the nuclear triad — intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and nuclear-capable Air Force bombers — some lawmakers have proposed deleting the ICBM arm of the triad, reducing it to a so-called “dyad.”

Under the Investing in Cures Before Missiles (ICBM) Act, for example, Congressional Democrats are seeking to introduce legislation that transfers $1 billion in funding from the Air Force’s future ICBM, the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent, or GBSD, which is expected to cost a total cost of around $264 billion, and instead spend it on developing a new COVID vaccine.

The act would commission an independent study to explore options for further extending the life of the current Minuteman III ICBM to 2050, which would include undisclosed “force structure changes.” It is not clear, however, if the veteran ICBMs would ultimately be replaced at a later date, or if the capability would be lost entirely after this date.

Other arguments have been made against ICBMs, more generally, too. The Minuteman III silos are nicknamed the “nuclear sponge” for good reason. The 400 missiles are in fixed silos, the primary job of which it is to be saturated with enemy warheads that could be used on other targets. The result is that Russia needs to invest heavily into the means to take out the American ICBM force.

Meanwhile, the Pentagon has continued to push for GBSD to replace the Minuteman III, which first became operational in the early 1970s, and which it argues is now too old to be further upgraded in a cost-effective manner.

Were the ICBMs to go, and putting aside the bombers, Admiral Richard said his command would rely entirely on SLBMs to provide the day-to-day deterrent. This is effectively the case already, these missiles arming the current 14 Ohio-class nuclear-powered, ballistic missile-carrying submarines (SSBNs) in service — another four of these boats have been adapted for conventionally armed operations.

The argument for the Air Force’s nuclear-capable bombers to resume round-the-clock alert status is not a new one, however.

Back in 2017 The War Zone

reported on how the Air Force’s top officer General David Goldfein said the service was preparing to possibly put some of its nuclear-capable bombers back on 24-hour alert for the first time in more than 25 years.

As we pointed out at the time, there are a number of arguments to be made against this proposal, including the risk of accidents, allocation of funding and other resources, and the consequent reductions in other parts of America’s nuclear arsenal. Then, of course, there are the reactions of potential opponents, including Russia and China. Both Russia and China would certainly be able to follow suit, to some extent, with their own bomber fleets.

Admiral Richard’s new argument for keeping ICBMs also seems to tacitly imply that putting bombers back on 24/7 alert is not the most effective use of resources — or the best deterrent.

In his written testimony, Richard also provides another argument against the removal of the ICBMs, in that it would effectively promote China to the status of nuclear peer.

While the point regarding China may be arguable and certainly depends upon various different factors, it seems certain the fact that China is fast heading toward a functional triad while the US is considering getting rid of a leg of its own will be a key part of this discussion going forward.

Against this backdrop, too, is an already-infamous tweet from Richard’s own command, which suggested that: “We must account for the possibility of conflict leading to conditions which could very rapidly drive an adversary to consider nuclear use as their least bad option.”

That sentence was provided as part of STRATCOM’s Posture Statement Preview, while the complete passage provides more detail:

Deterrence fundamentals against such threats have not changed. We drive to deny any adversary their aim, or impose a cost greater than what they seek, such that the benefit of restraint outweighs the perceived benefit of their possible action. These deterrence fundamentals apply from gray-zone activities through nuclear use. The spectrum of conflict today, however, is neither linear nor predictable. We must account for the possibility of conflict leading to conditions which could very rapidly drive an adversary to consider nuclear use as their least bad option.

As such, the statement tells us more about U.S. posture than any indication of impending nuclear Armageddon, despite the apparent urgency of the tweet. On the other hand, it’s notable that it comes amid growing fears related to the ongoing build-up of Russian forces close to the borders of Ukraine.

Russia, in particular, has been identified in the past as a potential candidate to employ an “escalate-to-deescalate” strategy in just that type of context. Escalate-to-deescalate supposes that, in certain situations, Moscow would consider using limited nuclear strikes in a regional conflict as a means of rapidly bringing a freeze to the fighting after desired gains before negotiating an end open hostilities. The idea is that the next step, a nuclear response, could be potentially so dangerous that immediate negotiations would commence. For their part, Russian leaders have steadfastly refuted that they have any such plans within their nuclear doctrine.

Regardless, the recommendation from the STRATCOM boss that bombers could once again stand alert — albeit under high particular circumstances — is a significant one.

Since Richard’s remarks on bomber alert are not part of the written testimony, details on what exactly he had in mind as regards practicalities are scarce. After all, there is a significant difference between ground alert, which came to an end in September 1991, and airborne alert, the latter being undertaken by Strategic Air Command B-52 for a period between 1960 and 1968.

Since Air Force bombers don’t currently sit on permanent readiness armed with nuclear weapons, let alone fly, any effort to go back to a higher degree of alert status would first involve ground readiness.

With its current fleet of bombers, it’s not clear what kind of ground alert would be possible, even providing that new infrastructure, additional manpower, and training could be made available to support that initiative. Air Force B-1s are now no longer nuclear capable, while the B-2s, which can carry nuclear weapons, and B-52s, some of which can, are also kept busy on conventional missions, using an ever-increasing range of ordnance, with combat operations and deployments all around the globe. The forthcoming B-21 Raider, although it will carry both nuclear and conventional weapons, will also be much more than just a bomber, meaning additional pressure on the fleet is a portion was assigned ground alert duty.

The nature of strategic arms control agreements between the United States and Russia also means the U.S. military can only field a certain number of nuclear-capable bombers. And, with a fixed number of nuclear warheads permitted for each delivery platform at any one time, loading nuclear warheads onto an aircraft means reducing them on other delivery systems.

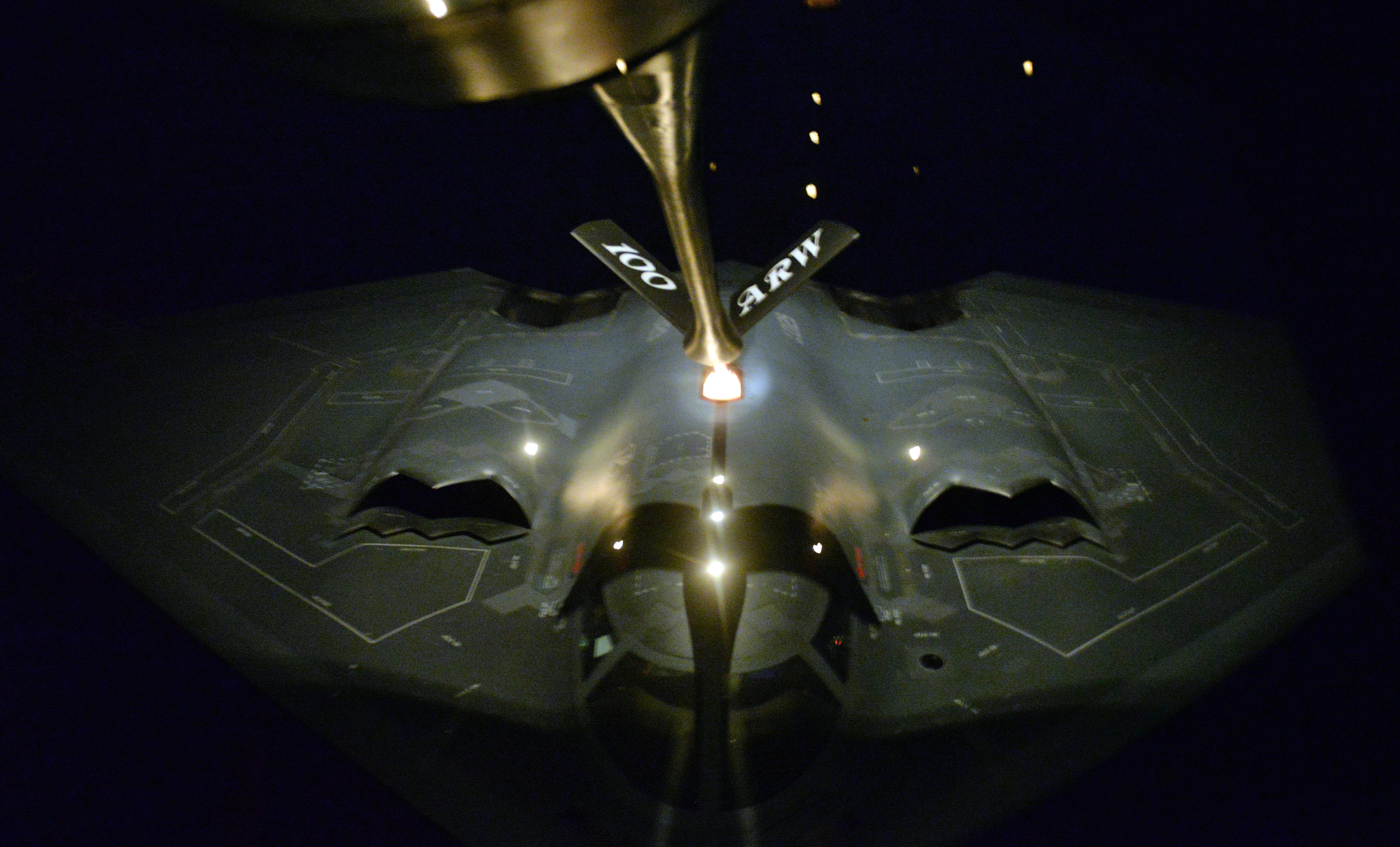

This is all before taking into account the other support aircraft that would be needed to execute this kind of round-the-clock mission. As well as tanker capacity, bomber ground alert would also require new taskings for the appropriate command and control aircraft, such as the E-4B Nightwatch and the E-6B Mercury.

“Really it depends on who, what kind of behavior are we talking about, and whether they’re paying attention to our readiness status,” Goldfein said back in 2017 when asked about whether or not the alert posture would help deter potential enemies. “I’ve challenged… Air Force Global Strike Command to help lead the dialog, help with this discussion about ‘What does conventional conflict look like with a nuclear element?’ and ‘Do we respond as a global force if that were to occur?’ and ‘What are the options?’”

While discussions about bomber alert made it to the top of the Air Force chain of command back in 2017, STRATCOM has so far opted against its return.

On the other hand, an argument could also be made that doing way with ICBMs and putting more resources into bombers could make sound strategic sense. Bombers are inherently more scalable and flexible than ICBMs, and SLBMs. Their crews are also already trained to get into the air quickly, when they need to use “minimum interval takeoffs.”

In contrast to a ballistic missile, whether launched from a relatively vulnerable silo, or a far more survivable submarine, a bombers can make itself known near a target area without unleashing its nuclear payload, providing a very clear deterrent signal. They can also be diverted to other targets if required, at any point before — or even after — weapons delivery.

In the mind of the public, however, the critical factor in bomber ground alert is probably the aspect of nuclear safety and security. As we have recounted in the past, the U.S. has had 32 incidents involving nuclear weapons, known as “Broken Arrow” events, since 1950, a number of these involving plane crashes or other aerial mishaps. In 2007, long after alert duty had come to an end, there were serious repercussions after crews accidentally loaded six AGM-129 Advanced Cruise Missiles, each with a live nuclear warhead, onto a B-52H that then flew from Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota to Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana.

As well as the security of the bombers and their deadly cargoes, there’s also the fact that base infrastructure would not only need to revert to a mission last flown in the Cold War, but also be adapted to take into account new threats, be they electronic or cyber attacks, to ensure the warheads are safe at all times.

All in all, whatever the strategic arguments for a ground bomber alert, the costs involved in reinstating such a capability would be significant, although not, in all likelihood, anywhere near the $264-billion price tag expected for GBSD. Indeed, were even a fraction of the funds to be redirected away from that program, that could, in turn, buy many more B-21s capable of performing nuclear and conventional missions, and have a survivable long-range cruise missile to do it as well. Some of those funds could also expand and bolster the Columbia-class future nuclear ballistic missile submarine program, which also has major downstream impacts on future conventionally-armed submarine programs.

For now, at least, whether the prospect of ground bomber alert makes sense or not within the framework of U.S. nuclear deterrence, is less important. Instead, it is being used as a tool to dissuade lawmakers from seeking to abandon ICBMs and, with the controversy that surrounds that objective, it may not be the last we hear of it.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com