The commander of U.S. Strategic Command has said he wants open-source intelligence communities to continue to look for new Chinese intercontinental ballistic missile silos, recent evidence for which has been provided to the public exclusively from non-governmental sources, rather than the Pentagon. This also seems to underscore assessments the U.S. military community has made in recent years about the fast-paced expansion and modernization of Chinese strategic nuclear forces, but for which it has provided limited evidence of itself. At the same time, this position points to the fact that open-source intelligence (OSINT) is in many ways changing the way that national governments go about this kind of work.

Speaking at the Space & Missile Defense Symposium (SMD) in Huntsville, Alabama, today, the STRATCOM boss, Admiral Charles “Chas” A. Richard, made direct reference to the non-military OSINT experts who have, in recent months, discovered what they consider to be multiple new Chinese intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) fields, in two different locations in the northwest of that country, that are large and appear to point to a considerable expansion of China’s nuclear arsenal.

“I usually have to pay someone to do that,” Richard observed, suggesting that those same independent OSINT analysts, and others, should continue to search for other Chinese silos, too. “If you enjoy looking at commercial satellite imagery or stuff in China, can I suggest you keep looking?” the admiral said, strongly suggesting that there are more silos yet to be found.

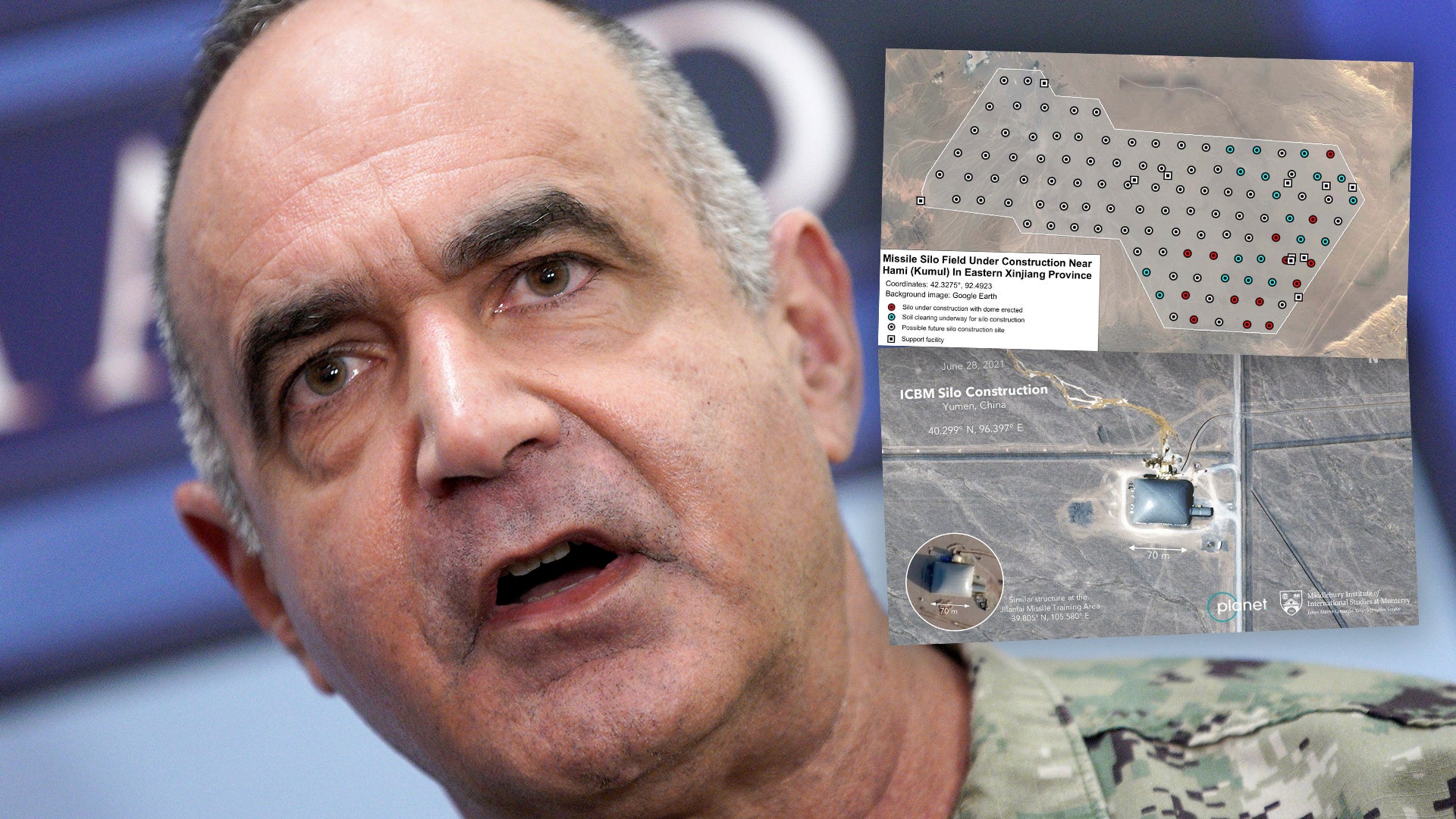

In late June, the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies used imagery provided by private firm Planet Labs to identify what appears to be an ICBM field, with more than 100 silos, under construction in the Gobi Desert near Yumen in China’s Gansu province.

Less than a month later, an apparent new field of silos, also under construction, was identified by Matt Korda and Hans Kristensen from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). Seemingly destined to house 120 missile silos, it’s located near the city of Hami in the eastern end of Xinjiang province.

The analysts responsible for finding the second silo field described it as “the most significant expansion of the Chinese nuclear arsenal ever.”

Just today, Roderick Lee from the China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI) appeared to have uncovered a third such ICBM site, under construction in Hanggin Banner, Ordos City, Inner Mongolia, using images taken by the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2 mission.

In the past, the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) has relied upon a small force of around 20 silos for its liquid-fueled DF-5 missiles, the only operational silo-based ICBMs in its inventory. A handful of other silos are used for training and test purposes.

With that in mind, the two new reported ICBM fields, and a possible third, suggest a fundamental overhaul of Beijing’s ICBM deterrent, apparently based around presenting enemies with a much more challenging target, should they wish to destroy it in a first strike. These new missile fields could also provide China with an expansive quick-launch ICBM capability the likes of which they didn’t have before.

In his address today, Admiral Richard referred to the ICBM fields, as part of a pattern in the wider expansion of China’s military capabilities.

“The explosive growth in their nuclear and conventional forces can only be what I describe as breathtaking,” Richard said, adding that, “frankly, that word ‘breathtaking’ may not be enough.”

This kind of analysis is in keeping with warnings about China’s growing military might from the Pentagon last year in its report to Congress on the Chinese military and its capabilities. “The PLARF develops and fields a wide variety of conventional mobile ground-launched ballistic missiles and cruise missiles,” the report said. “The PRC [People’s Republic of China] is developing new intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) that will significantly improve its nuclear-capable missile forces.”

Interestingly, however, there had been a degree of skepticism in the past about the scale of China’s nuclear ambitions as presented in the Pentagon’s own estimates. The latest revelations, especially the silo fields, support the Pentagon’s original assertions and also seem to have convinced some previous critics of those predictions. STRATCOM has also confirmed its belief that the evidence does indeed show ICBM silos under construction, rather than wind farms, as some — including in the Chinese media — have suggested.

While the think tanks and OSINT experts continue to pore over publicly available sources for a better picture of China’s nuclear development path, it’s curious that STRATCOM, and the Pentagon as a whole, have effectively been deferring to organizations like Middlebury and FAS on this topic, rather than putting out findings from its own intelligence in some kind of declassified format. The tweet embedded below, which links to the New York Times report in which Korda and Kristensen of the FAS presented their findings, is a prime example of that tendency.

There are, of course, examples of the Pentagon putting out declassified imagery to underscore its assertions, as in the case of Russian-supplied fighter jets that have appeared in Libya. With that in mind, it remains curious that they haven’t done the same in the case of recent Chinese developments. After all, the use of Google Earth imagery by FAS in the case of the construction work at the ICBM silo field shows that unclassified imagery is readily available if they wanted to release this themselves. The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) has even set up an initiative to do just this, including working directly with research institutes and think tanks.

Nevertheless, there have even been some tantalizing hints in recent days of potentially game-changing Chinese developments in this field.

Also speaking at the SMD in SMD, Glen D. VanHerck, commander of U.S. Northern Command, said China “just demonstrated” a “very fast” hypersonic vehicle. Although no further details were provided, VanHerck said it would challenge current early warning systems. While this may be a reference to one of China’s previously disclosed hypersonic weapons, it could potentially be something altogether different. Either way, it is an example of the kind of information that the United States Intelligence Community clearly has access to.

Whatever STRATCOM knows or doesn’t know about China’s strategic weapons, it’s clear that there is a wider acknowledgment that the country is accelerating the pace of its military modernization as well as looking at increasingly more sophisticated and plentiful nuclear delivery systems.

At the same time, China’s growing nuclear capabilities have been a major point in the Pentagon’s argument for staying the course of hugely expensive nuclear modernization, too. But while they clearly want people to see evidence of this to bolster their case, so far, at least, this work has been left to non-government entities. It seems, for whatever reason, the Department of Defense is currently happy with this new paradigm in which the OSINT community can be left to carry out its work with satellite imagery while helping to bolster the Pentagon’s position.

Certainly, this approach seems to be opening different avenues for applying pressure on international opponents to explain what they’re doing and to raise support for ongoing investments in strategic capabilities.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com