A recent Air Force Magazine article has caused something of a stir after it highlighted systems and procedures that the U.S. Air Force employs to ensure it can still launch its Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missiles, if necessary, even if personnel in individual missile alert facilities are incapacitated for some reason. At first glance, it might appear that the United States has something of a “Dead Hand” arrangement to fire these world-ending weapons, drawing comparisons to systems the Soviet Union reportedly employed and that present-day Russia apparently still uses. However, a closer look at the American protocols shows the system is place is far from automatic and still has a number of checks and balances to prevent an inadvertent missile launch.

Air Force Magazine‘s Rachel S. Cohen included the mention of the need for watchstanders in missile alert facilities to routinely enter a “stand down” command into their control consoles in a recent story on Air Force Missileers. The publication of the piece followed the launch of an unarmed Minuteman III from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California as part of a routine test of the missile’s accuracy and reliability. The inert re-entry vehicle splashed down as intended some 4,200 miles away in the Pacific Ocean at Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands.

At present, the Air Force’s three Missile Wings oversee 400 Minuteman IIIs in silos spread across Montana, Nebraska, and North Dakota. Another 278 missiles are in inventory for testing and other purposes. Missileers stand watch in hardened underground alert facilities in the missile fields 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year.

“The Airmen also spend their time on routine inspections and sending messages to others in the operation and to the ICBM itself. Missileers must give the weapon system what is essentially a “stand-down” order every six hours,” Air Force Magazine‘s Cohen wrote in her recent piece. “If they don’t respond to that prompt within 10 minutes, the missiles will assume that its human operators are dead, and start looking for a launch command from one of the Pentagon’s nuclear mission control aircraft.”

For this description, it might seem as if the missile alert facility’s systems would begin initiating a launch sequence on its own if the operators were to miss one of the four prompts they get every day to let the computers known they’re still alive. However, the reality is far less extreme.

What the Air Force Magazine piece is describing is that missile alert facilities have a built-in backup arrangement where, if it appears that the human operators are no longer capable of performing their duties, it goes into a mode where it cuts them out of the launch sequence. However, it still needs to receive a valid launch code from an outside source and will not automatically fire any missiles on its own.

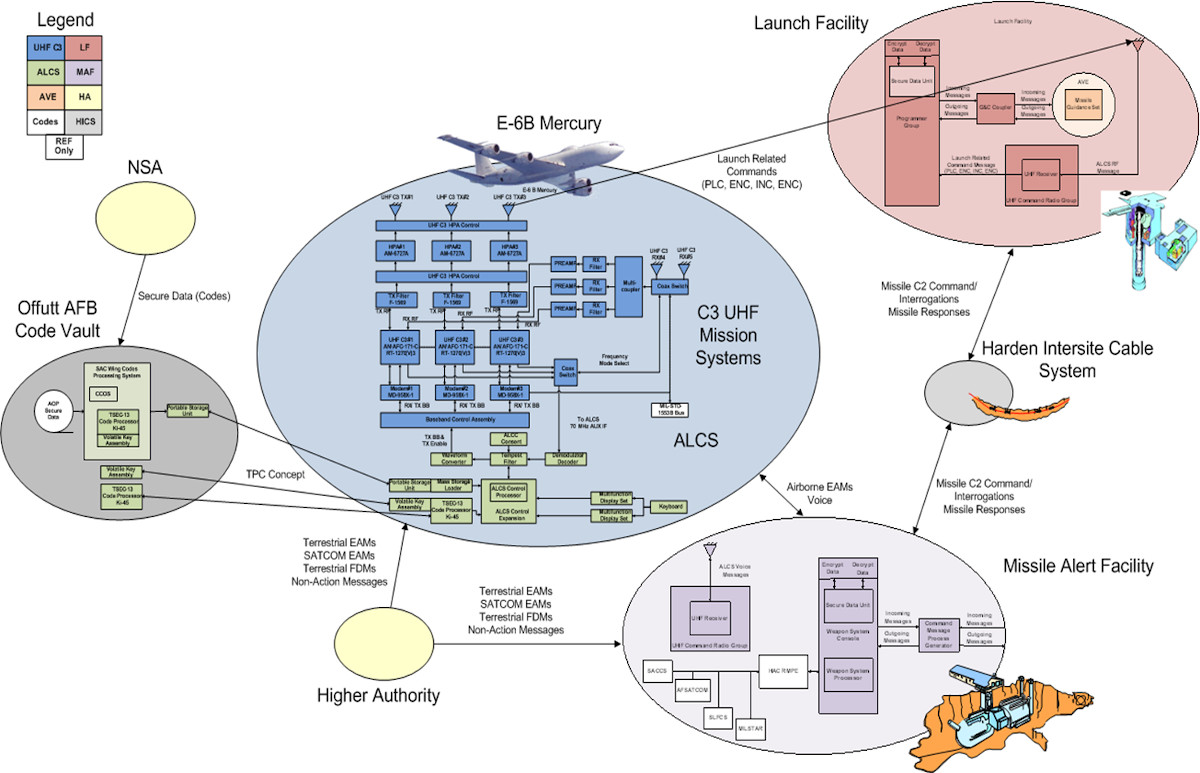

The U.S. military does have a fleet of E-6B Mercury airborne command post aircraft equipped with the Airborne Launch Control System (ALCS), which you read about in more detail in past War Zone

here and here, that do have the capability to remotely trigger a launch under various circumstances, something that is publicly known. They’re not flying around sending out launch codes by default, though.

“There are ZERO ABNCPs [airborne command posts] in the air to respond to an inquiry,” Robert Hopkins, a retired Air Force pilot and historian, wrote on Twitter. “ANY other [missile alert facility] capsule can respond, and failure to respond DOES NOT trigger a launch. It escalates inquiries.”

It’s also important to note that, in 1991, then-President George H.W. Bush ended the practice of keeping both nuclear-armed bombers and missile alert facilities on a 24-hour alert status that kept a number of them actively poised to strike targets in the Soviet Union and elsewhere at a moments notice. Today, the Air Force has a policy of so-called “open ocean targeting,” whereby its Minuteman IIIs are, by default, pointed at open areas of the sea, specifically to prevent a catastrophe from an accidental launch. During an actual crisis, personnel would need to re-target these weapons before firing them.

Today, the primary role of America’s ICBM force within the country’s nuclear triad is to act as as a “sponge” to “soak up” an opponent’s warheads, which could otherwise be employed against other targets. This has long called into question its basic utility, Dead Hand or not, especially when considering the costs of maintaining and modernizing it, something The War Zone

has highlighted in the past.

With regards to this prompt that Missileers get every six hours, it, like so many things about the Minuteman III ICBMs and their launch control systems, it seems like a holdover from the Cold War. President Bush’s 1991 decision to end the standing nuclear alert also led to the decommissioning of the AN/DRC-8 Emergency Rocket Communications System (ERCS). First introduced in 1963, this system consisted of a UHF signal repeater, capable of broadcasting an “Emergency Action Message” – something you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone piece – with a launch code, on top of a rocket. The Blue Scout test and space launch rocket was employed until 1968, when modified Minuteman IIIs took over this role.

During a nuclear attack, the Air Force could fire rockets with the AN/DRC-8, if necessary, which would then fly very low in space across the missile fields broadcasting the launch code. If the operators in the missile alert facilities down below were dead or otherwise incapacitated, one would imagine that the backup system in place would have then received the code and carried out the launch sequence automatically.

Again, as is the case today with the E-6Bs, there still would have had to have been an active decision to employ the ERCS, to begin with. Starting in 1967, EC-135 Looking Glass airborne command post aircraft, the predecessors to the E-6B Mercuries, also entered service to supplement the ERCS.

The very idea of an actual automatic “Dead Hand” trigger that could launch a massive nuclear retaliatory strike in the absence of a functioning human-operated command and control system, has been a controversial topic of discussion for decades because of the obvious concerns about possible accidents and malfunctions.

Starting in the 1960s, the Soviet Union reportedly began work on possible Dead Hand triggers, which eventually resulted in the development and fielding of a system called Perimeter. There are relatively few publicly known details about Perimeter to this day, but from what is known, it is very similar to the American ERCS, right down to including a rocket carrying a system to communicate a launch command to the country’s strategic missile forces down below.

There is a debate about just how automated Perimeter is or isn’t. For years, experts and scholars described it as an entirely automatic arrangement, akin to the famous fictional “Doomsday Machine” in Stanley Kubrick’s iconic 1964 Cold War black comedy Dr. Strangelove.

“In a crisis, military officials would send a coded message to the bunkers, switching on the dead hand,” a 1993 New York Times story said. “If nearby ground-level sensors detected a nuclear attack on Moscow, and if a break was detected in communications links with top military commanders, the system would send low-frequency signals over underground antennas to special rockets.”

However, David Hoffman, a longtime journalist, offered details suggesting it was much less automatic in his 2009 book Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and Its Dangerous Legacy and in subsequent interviews. Stories had already begun to emerge by that point that indicated that Perimeter was actually more “semi-automatic” in its functionality, just like its American counterpart.

“They [the Soviets] thought that they could help those leaders by creating an alternative system so that the leader could just press a button that would say: I delegate this to somebody else. I don’t know if there are missiles coming or not. Somebody else decide,” he told NPR‘s Terry Gross in 2009. “If that were the case, he [the Soviet leader] would flip on a system that would send a signal to a deep underground bunker in the shape of a globe where three duty officers sat. If there were real missiles and the Kremlin were hit and the Soviet leadership was wiped out, which is what they feared, those three guys in that deep underground bunker would have to decide whether to launch very small command rockets that would take off, fly across the huge vast territory of the Soviet Union and launch all their remaining missiles.

Still, even though the United States, and Russia, based on the most recent reporting, do not have automatic nuclear “Dead Hands” in place, the concept continues to a topic of interest. Deterrence theory relies explicitly on a country maintaining a credible “second strike” capability to respond to hostile nuclear strikes, no matter how devastating they might be. Right now, in the U.S. military, the Navy’s fleet of Ohio class ballistic missile submarines armed with Trident D5 submarine-launched ballistic missiles form the core of this retaliatory capability.

However, some fear that various new strategic weapon developments, such as Russia’s recent fielding of a small number of nuclear-armed Avangard hypersonic boost-glide vehicles, risk invalidating existing command and control protocols and their backups and fail-safes.

In August 2019, War on the Rocks

published a piece in which Dr. Adam Lowther, Director of Research and Education at the Louisiana Tech Research Institute, and Curtis McGiffin, Associate Dean, School of Strategic Force Studies, at the Air Force Institute of Technology, both of whom are also retired U.S. military officers, advocated for an actual American Dead Hand system. This proposal immediately proved to be controversial and prompted criticism from other scholars and experts.

It is worth noting that the U.S. military, while it is not publicly pursuing a Dead Hand of some kind, has been working hard in recent years to upgrade and improve the capabilities of its nuclear command and control architecture and the reliability of new and existing systems, in the face of a variety of threats, including cyberattacks. Last year, the Air Force notably released an entirely revised edition of the unclassified Air Force Instruction 13-550, Air Force Nuclear Command, Control, and Communications (NC3). The new manual focused heavily on the need for increased “resilience,” that is to say systems that can reliably resist attacks, especially against cyber threats, as well as electromagnetic pulses.

The U.S. military is also seeking improvements to the Airborne Launch Control System and a replacement for the E-6Bs. The future Survivable Airborne Operations Center (SAOC) aircraft are also expected to serve as a replacement for the Air Force’s E-4B Nightwatch airborne command posts and its C-32A Air Force Two VIP transports. The E-4B had briefly carried the ALCS, as well, but no longer have this capability.

The United States is also in the midst of a major modernization of its nuclear capabilities, across the board, and the associated infrastructure that goes along with that deterrent, which estimates have said could cost at least $1.2 trillion over the next 30 years. The upcoming budget proposal from President Donald Trump’s Administration for the 2021 Fiscal Year, which is slated to be released publicly next week, will seek to add billions more in funding for nuclear weapons-related projects. The War Zone has questioned in the past whether this is at all sustainable, or even logical, over such a long period.

Whatever happens to the U.S. government’s plans to modernize the country’s nuclear deterrent capabilities, there’s no indication that it is looking to implement a Dead Hand trigger for its ICBMs, or any other weapon systems. There’s no evidence is has one in place now, either.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com