At the latest official public count, the U.S. military possesses a stockpile of 3,750 nuclear warheads, with approximately 2,000 more that have been retired and are awaiting disposal. Under the Trump administration, however, a small but unusual bump in stockpile size occurred between 2018 and 2019, according to these same figures. The unexplained increase in the total number of warheads in inventory is apparently only the second reported instance of its kind since the end of the Cold War.

The revelations are among newly declassified details of nuclear weapons numbers in a recently published fact sheet from the U.S. Department of State with the title Transparency in the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Stockpile. This is the first time such data has been released since September 2017, after which the Trump administration took the decision to classify the information.

As the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) observed in their blog on the topic, the stockpile increased by 20 warheads between September 2018 and September 2019, when Trump was in office.

While there is no information immediately available to explain that 20-warhead increase, FAS suggests that one possibility is the production of the controversial low-yield W76-2 nuclear warheads for the U.S. Navy’s Trident D5 submarine-launched ballistic missiles.

The-then presidential candidate Joe Biden warned before taking office that fielding the W76-2 was a “bad idea” and that the warhead’s existence makes the U.S. government “more inclined to use them” than in the past.

Regardless, the Trump administration pushed forward with the production of the W76-2, pointing to Russian plans for the first use of tactical nuclear weapons as justification.

According to FAS, the first W76-2 was produced in February 2019 and the final example was completed in June 2020. While that might explain some of the background to the spike, it’s not conclusive, especially since the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) has gone on the record to say that some W76-1s were converted into W76-2s, which wouldn’t result in any change in the total number of warheads in the stockpile.

Another possibility relates the spike to the Nuclear Posture Review under the Trump administration, which was released in 2018. This reversed the existing plan to completely remove the B83-1 gravity bomb from service. It could be that the bump reflects a change in retirement schedules there somehow, although the timeline doesn’t seem to match up.

Whatever the reason for the spike, the appearance of the newly declassified data is interesting in itself. The State Department fact sheet notes that “Increasing the transparency of states’ nuclear stockpiles is important to nonproliferation and disarmament efforts, including commitments under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and efforts to address all types of nuclear weapons, including deployed and non-deployed, and strategic and non-strategic.”

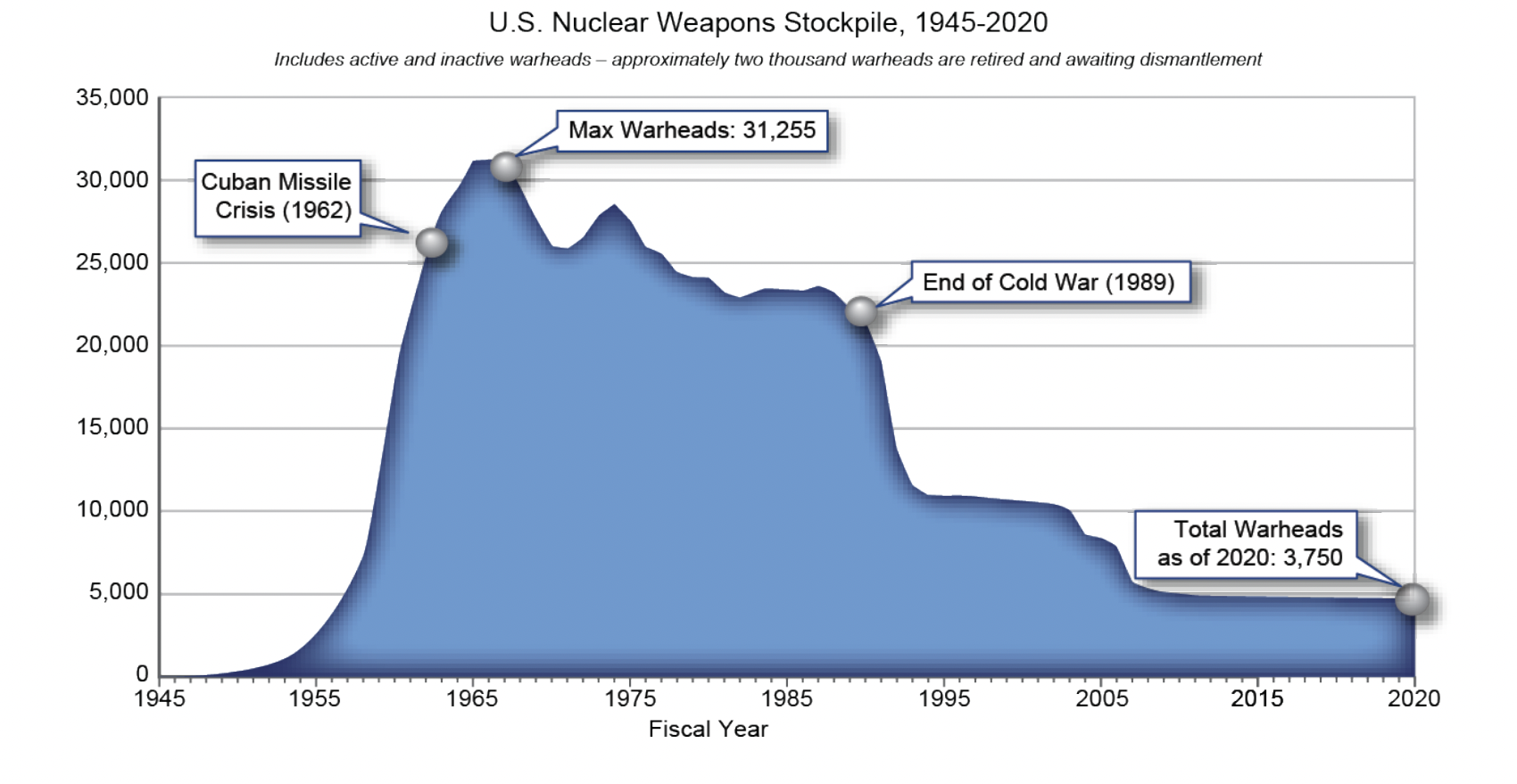

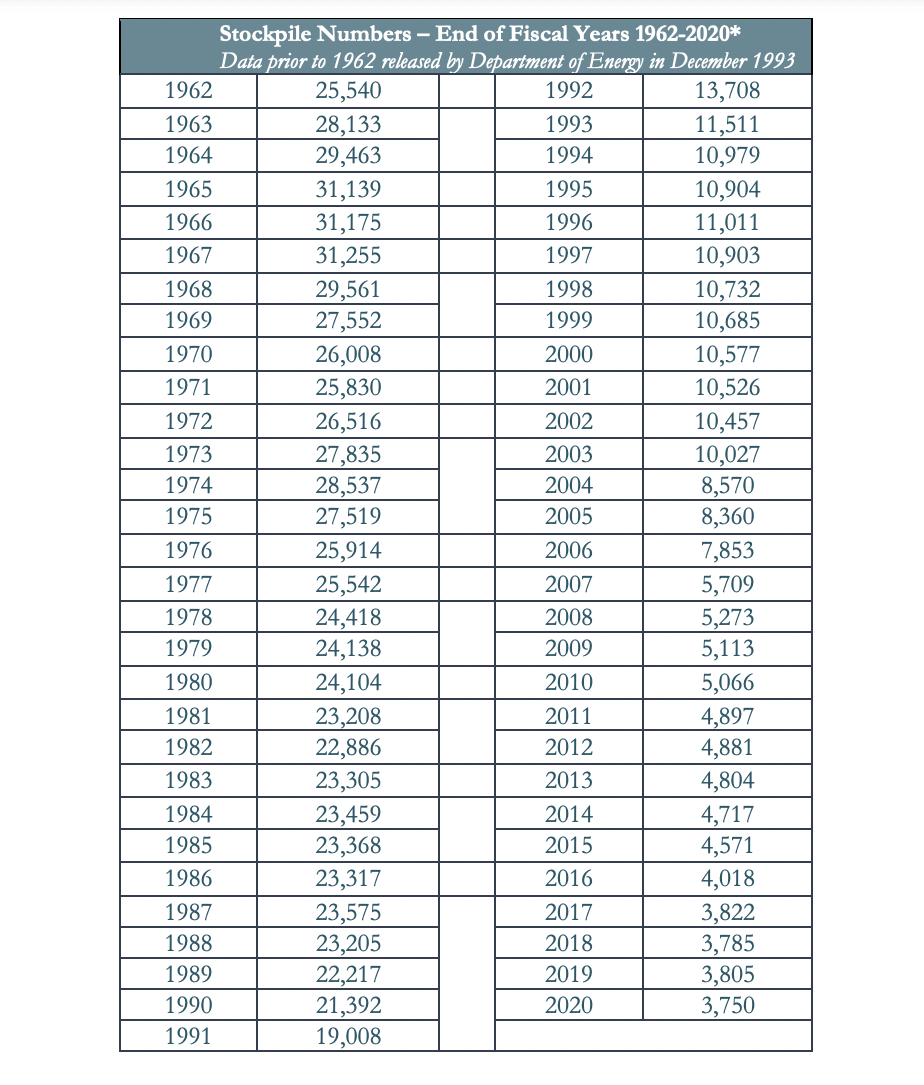

The latest figures are correct as of September last year, revealing that the U.S. has dismantled 711 nuclear warheads since September 30, 2017, when the figures were last made public. Prior to then, the United States had 4,717 nuclear warheads in its stockpile as of September 2014, and 5,113 warheads in September 2009.

It’s also worth noting the classification for warheads in the stockpile, and those that have been retired. The nuclear stockpile includes both operational “ready-for-use” warheads as well as non-operational ones, kept in a depot, which would require longer to make ready. Meanwhile, retired warheads are removed from their delivery platform and are no longer functional, essentially waiting to be dismantled.

The fact sheet also compares the latest total to the peak of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile — 31,255 warheads in Fiscal Year 1967 — and the total at the end of the Cold War — 22,217 in late 1989.

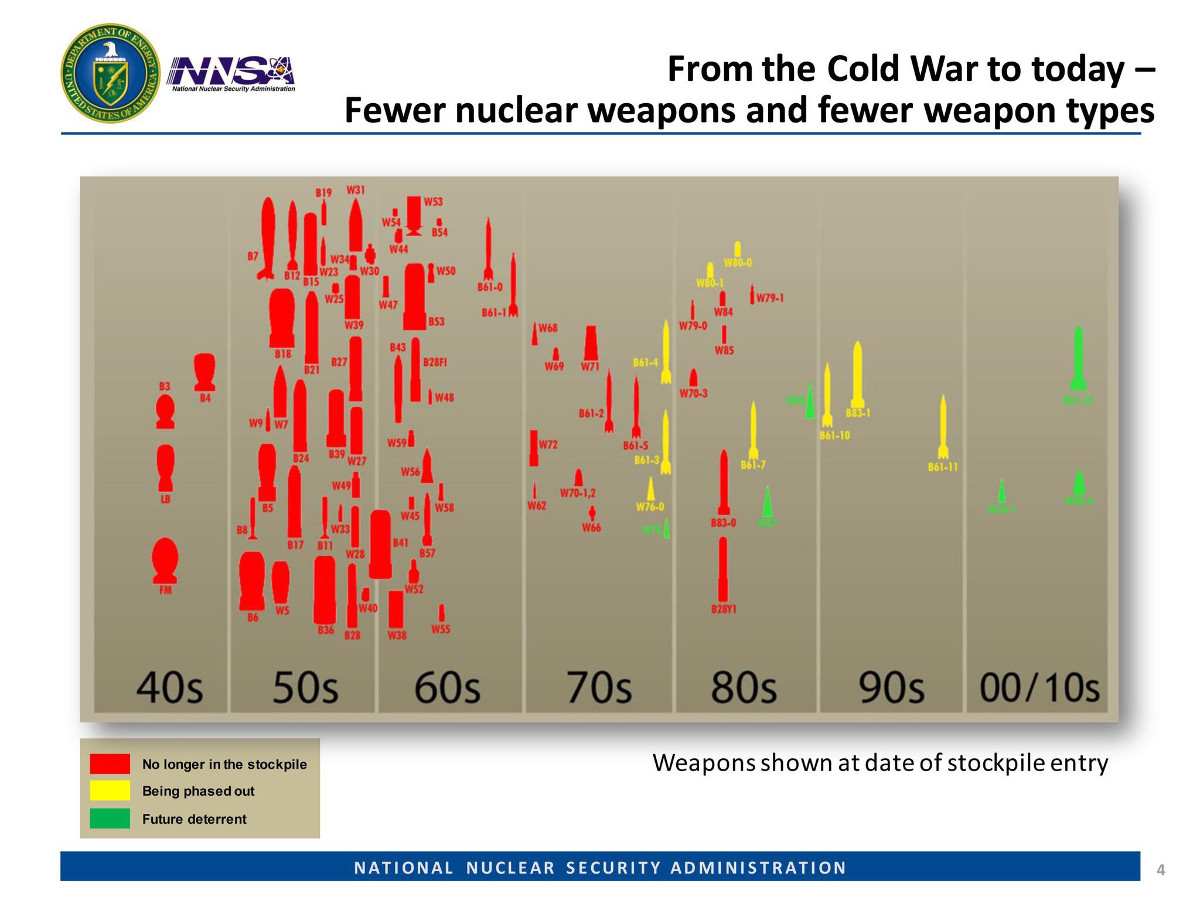

The figures do not provide subtotals of strategic and tactical weapons, although the fact sheet does confirm that numbers of U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons have declined by more than 90 percent since September 1991. In the past, this category included weapons such as nuclear mines, artillery, tactical ballistic missiles, tactical cruise missiles, tactical gravity bombs, and anti-submarine weapons. Today, this class of weapon has been reduced to gravity bombs, although modernization of these weapons continues.

The timing of the latest nuclear warheads fact sheet coincides with a review of nuclear weapons policy and capabilities by the Biden administration. Declassifying the nuclear stockpile information is also likely geared toward next January’s Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty conference, in which nuclear powers who have signed the treaty — among the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, and China — will address the issue of disarmament commitments.

The State Department’s move could therefore be intended to apply pressure on Russia and China in particular, to release more details about their prospective nuclear stockpiles. Both of those countries are in the process of introducing new and diverse strategic weapons capabilities, while China is thought to have embarked on a considerable expansion of its nuclear delivery systems.

In the case of Russia, the Biden administration may hope that the newly released details encourage Moscow to be more transparent about its own nuclear stockpile within the framework of further extending, or replacing the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or New START. China, for its part, is not a signatory of New START and while the Biden administration is expected to make a push to include Beijing as well, officials there have been lukewarm in the past about becoming involved in such treaties.

As The War Zone has examined in the past, New START places hard limits on the total number of strategic nuclear weapon delivery systems, as well as the warheads that they carry, that each country can possess. The arrangement is seen as being key to preventing a new nuclear arms race between the two powers and the Biden administration is apparently keen to negotiate new arms control deals with Russia, especially given the collapse of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, or INF, in 2019.

In terms of nuclear policy, the Biden administration, for its part, seems set on continuing much of the strategic weapons modernization that was already underway during the Trump administration, despite the president-elect making calls for reducing spending on nuclear weapons, even stating that “the United States does not need new nuclear weapons.”

Current modernization plans now include replacing LGM-30G Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missiles with the future Ground Based Strategic Deterrent, or GBSD, at a total cost of around $264 billion. For the Navy, as well as the aforementioned W76-2 warhead, there are also longer-term plans for new ballistic missile submarines as well as upgrades for the Trident SLBMs to keep them viable until the 2040s.

The Air Force, meanwhile, expects to receive around 1,000 examples of the stealthy Long-Range Standoff (LRSO) cruise missile to replace the existing Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM), to be armed with refurbished W80-4 warheads. This is in addition to its revitalized inventory of tactical nuclear weapons, based around the B61-12 gravity bomb. While the LRSO program has a projected cost of $16.2 billion, the B61-12 is notoriously worth more than twice its weight in gold, as The War Zone has examined in the past.

That suggests that despite pre-election rhetoric about pursuing a “sustainable nuclear budget,” the nuclear weapons plans of the current administration are more or less business as usual. The hopes of some analysts that the United States might even do away with the ICBM leg of its nuclear triad were swiftly dashed, the Biden administration quickly committing itself to the primacy of the nuclear triad itself — ICBMs, nuclear-capable Air Force bombers, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles. All of those areas are undergoing a process of modernization.

On the other hand, the latest nuclear weapons fact sheet does seem to signal a clear move toward increasing transparency in terms of nuclear stockpiles. While this would seem calculated as a way of exerting pressure on Russia and China to increase their own levels of transparency in this regard, it remains to be seen how effective that policy might be.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com