The U.S. Air Force has awarded two new major contracts as part of its plans to replace America’s existing and aging nuclear-tipped LGM-30G Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) arsenal, one of the three legs in the country’s “Nuclear Triad” deterrence concept. The announcements come amidst an on-going Pentagon-wide nuclear posture review, which could potentially have an impact on the future of the land-based missile force as a whole.

On Aug. 21, 2017, in its daily contracting alert, the Pentagon announced the deals with Boeing and Northrop Grumman to mature their respective designs and conduct additional risk reduction work as part of the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) program, which aims to develop an all-new replacement for the Minuteman IIIs. Boeing’s contract was valued at more than $349 million, with Northrop Grumman’s deal was worth almost $329 million. It is not immediately clear why the two contracts, ostensibly for the same work, differ by such a significant amount.

The Air Force declined to pursue an offer from a third bidder, top defense contractor Lockheed Martin, which had also been the only competitor to name its main sub-contractor partners, which included General Dynamics, Draper Laboratories, Moog, and Bechtel. Lockheed Martin also planned to work with both Orbital ATK and Aerojet Rocketdyne to procure the rocket motors for its new missiles. However, in 2016, the Air Force had already banned competitors from making exclusive arrangements with either firm.

“We are moving forward with modernization of the ground-based leg of the nuclear triad,” Secretary of the Air Force Heather Wilson said in an official statement. “Things just wear out, and it becomes more expensive to maintain them than to replace them. We need to cost-effectively modernize.”

“GBSD is the most cost-effective ICBM replacement strategy, leveraging existing infrastructure while also implementing mature, modern technologies and more efficient operations, maintenance and security concepts,” U.S. Air Force General Robin Rand, head of Air Force Global Strike Command, the service’s top strategic headquarters, added.

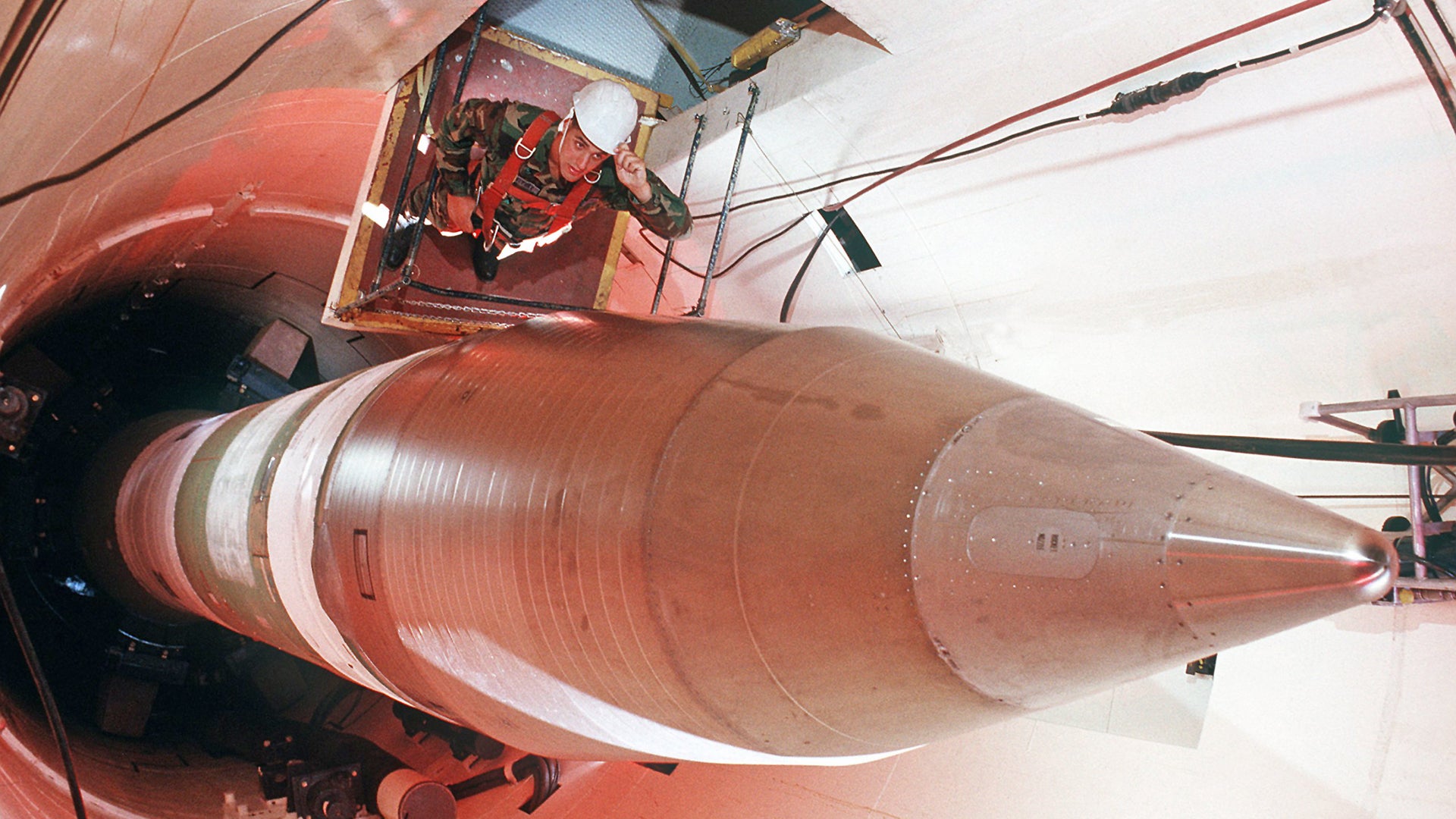

The new ICBMs are expected to replace the Air Force’s present arsenal of approximately 500 LGM-30G Minuteman III missiles. Per international agreements, the present missiles contain either a single W78 or W87 thermonuclear warhead. The W78 has an estimated yield of up to 350 kilotons of TNT, while the W87 may have a boosted yield of up to 475 kilotons. It is unclear whether the more powerful W87 variant was actually fielded or was just a prototype design.

The original Minuteman entered service in the 1960s and received regular improvements, eventually leading to the Minuteman III configuration in the 1970s. The Air Force says it is no longer feasibly to simply upgrade the existing missiles to defeat future threats.

“The warfighter needs these capabilities and we can’t just make incremental improvements to Minuteman III,” U.S. Air Force Colonel Heath Collins, the System Program Manager for the GBSD program at the Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center’s ICBM Systems Directorate at Hill Air Force Base in Utah, explained earlier in 2017. “It would be like taking your VHS player and trying to make it a Blu-Ray player by swapping out parts.”

But as Secretary Wilson noted, these weapons are simply getting old and are therefore in need of a complete replacement. Based on the information available, Boeing and Northrop Grumman are looking to develop new designs that are more reliable and feature improved protections against emerging threats, specifically cyber attacks.

On top of that, there is a concern that the dated Minuteman III design could be increasingly vulnerable to future enemy ballistic missile defenses. Spurred on by their concerns about such developments in the United States, both Russia and China appear to be working on new ballistic missile defenses, along with other anti-satellite weapons and advanced networked air defenses.

“The Minuteman III will have a difficult time surviving in the active anti-access, area denial environment that we will be dealing with in the 2030 and beyond time period,” General Rand told members of Congress during a hearing in March 2016. Three months later, there were unconfirmed reports that the Chinese military had tested a new missile defense interceptor.

As such, the Air Force could be looking for missiles with improved countermeasures systems to defeat a variety of ground, airborne, and space-based anti-ballistic missile systems and early warning sensors. Since the Cold War, the service has been actively working on steadily improving physical decoys, effectively metallic balloons that mimic the shape and characteristics of an actual warhead, that make it harder for defenders to target the real threat.

Much of the actual design requirements for the new GBSD are classified, which isn’t surprising given the sensitivity of America’s nuclear deterrent. The Air Force has made it clear that it is looking to save money on its new weapons by focusing on modular components that can easily accept upgrades throughout the weapon’s lifetime.

As General Rand alluded to, it is likely that the new missiles will fit in the Minuteman III silos and make use of other existing systems, at least initially. The Air Force is pursuing a separate program to upgrade various portions of its nuclear command and control architecture and is working with the U.S. Navy on updating communication systems both services operate jointly to assure U.S. officials can talk with ballistic missile submarines during a crisis.

On top of that, the Air Force clearly hopes to leverage the existing experience of Boeing and Northrop Grumman to help keep costs down. Both companies have long been involved in the Minuteman III program.

“Since the first Minuteman launch in 1961, the U.S. Air Force has relied on our technologies for a safe, secure and reliable ICBM force,” Frank McCall, Boeing’s director of Strategic Deterrence Systems and the program manager for the company’s GBSD project, said in a statement. “As the Air Force prepares to replace the Minuteman III, we will once again answer the call by drawing on the best of Boeing to deliver the capability, flexibility and affordability the mission requires.”

“We look forward to the opportunity to provide the nation with a modern strategic deterrent system that is secure, resilient and affordable,” Wes Bush, chairman, chief executive officer, and president of Northrop Grumman, said in a separate release. “As a trusted partner and technical integrator for the Air Force’s ICBM systems for more than 60 years, we are proud to continue our work to protect and defend our nation through its strategic deterrent capabilities.”

The Air Force has estimated the entire GBSD project could cost more than $62 billion. The Pentagon’s office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation arrived at a significantly higher estimate, placing the final price tag for the program at between $85 and $100 billion. In addition, these figures do not necessarily take into account the full spectrum of funds necessary for routine maintenance and regular improvements after the new missiles enter service.

The total program cost is an especially important consideration in this case since the Air Force is presently in the midst of a host of other expensive modernization projects, including continued development of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, work on the new B-21 Raider stealth bomber and follow-on sixth generation stealth fighter jet concepts, and other critical assets like the KC-46 tanker and possible successors. There’s also just the need to maintain and update existing fleets of aircraft to support immediate operational needs. All of this begs the question of whether the service can afford to spend hundreds of millions to replace hundreds of missiles of potentially dubious utility.

Sustaining the missile force isn’t just a matter of the IBCMs, their silos, and the command and control systems, as well. The vast missile fields require a significant security presence that needs modernizing, too. Most notably, the Air Force has struggled to find the necessary resources to replace aging UH-1N Twin Huey helicopters that patrol the sites and are on call to respond to an emergency.

There’s also a long-standing and serious concern about the morale of missile units, with many missileers describing it as a “dead-end career” in a service that unsurprisingly gives preference for promotion to its members who fly airplanes, and fast ones in particular. In 2013, the ICBM force suffered a particularly damning string of high profile scandals that prompted a major Air Force review of the conditions throughout the missile force.

Ahead of the Pentagon’s announcement of its latest nuclear posture review, The War Zone’s own Tyler Rogoway explained the issues with modernizing ICBM force in detail, writing:

What I propose is controversial, but I think it is wise. At the very least, the Pentagon needs to deeply review options for reorganizing America’s nuclear triad into a nuclear dyad. America’s tired land based intercontinental ballistic missile program could be retired, and those many tens of billions of dollars could refocused to build a larger, far better funded nuclear ballistic missile submarine force. The Air Force would also receive a large portion of those savings to buy the B-21 Raider stealth bomber force it says it desperately needs, as well as a new very stealthy and smart nuclear-tipped cruise missile to go along with it.

There is no doubt that some will oppose screwing with the nuclear triad at all, but the fact is hundreds of billions of dollars are required over the next decade to modernize the triad, and still capability sacrifices will have to be made. Yes, America’s ICBMs would theoretically work as a strategic “sponge” to soak up hundreds of enemy warheads during a nuclear exchange, but that strategy can be viewed as flawed on multiple levels. The fact is, the land-based leg of our nuclear arsenal is disposable, and the money it sucks up and will continue to suck up can be used to bolster the other two legs of the triad to an extreme degree.

Also, by eliminating the land-based ICBM leg of the triad, not only can the other two legs be greatly improved, but advances in conventional war fighting capability can also be realized as a secondary result.

With all of these considerations it’s not surprising that there’s some indication that support for at least considering eliminating the ICBM force might be growing within the U.S. military. Earlier in August 2017, during a gathering at Naval Base Kitsap in Washington State, a U.S. Navy sailor pointedly asked Secretary of Defense James Mattis about whether the Pentagon really planned to maintain all three legs of the nuclear triad.

“I think we’re going to keep all three legs of the deterrent,” Mattis said, but immediately left open the possibility that the nuclear posture review could recommend otherwise. “I think we need the other two legs [bombers and IBCMs]. But I’ve got to wait until the posture review is done.”

In the meantime, Boeing and Northrop Grumman will continue refining their GBSD designs. But by the time they’re ready to move onto the next phase of the program, the very future of America’s ICBM force may have changed itself.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com