More than a decade after the end of World War II, the Central Intelligence Agency initiated a project to develop an air-driven siren that it could readily attach to a small aircraft for psychological warfare operations. The inspiration for this device, dubbed the Jericho Horn, was a similar system the Nazis had employed on the legendary Ju-87 Stuka dive bomber. In the end, the CIA tracked down the designer of that siren and scoured museums in the United States for information about the Stuka before building its own prototypes.

An unknown CIA officer appears to have first made a handwritten request for “a siren or screamer type noisemaker for psychological warfare” for use on an aircraft on May 8, 1958, kicking off what was also referred to as the “Screamer Project.” The exact reason why the Agency wanted this device is unclear, but “the device is to be used in conjunction with a current high priority Agency project,” according to another report, requesting to initiate “Task S,” dated Sept. 5, 1958. Other records say that the requirement originated with the CIA’s Far East Division. These and other documents related to the Jericho Horn effort are now declassified, with significant redactions, and available online via the CIA Records Search Tool, or CREST.

The handwritten document says that the CIA wanted the horn to be able to work with a P-51 Mustang propeller-engine fighter. The Agency wanted it to be able to be sufficiently disconcerting with the aircraft flying at speeds between 280 and 300 miles per hour and at an altitude of just 300 feet.

This proposed combination is not necessarily surprising. In the first few decades after its creation in 1947, the Agency regularly used a wide array of surplus World War II-era aircraft for covert operations around the world. During the CIA-orchestrated overthrow of Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz in 1954, a mercenary-piloted P-47 Thunderbolt notably bombed the city of Chiquimula, some 65 miles east of Guatemala City, as part of associated psychological warfare effort to demoralize and confuse regime forces.

The problem was that the CIA appears to have had no idea about how to go about building such a thing. “Dan says it can be done, but if program is to be a fresh start considerable time & money are involved,” the initial handwritten request explained. There is no hint as to who this “Dan” might have been.

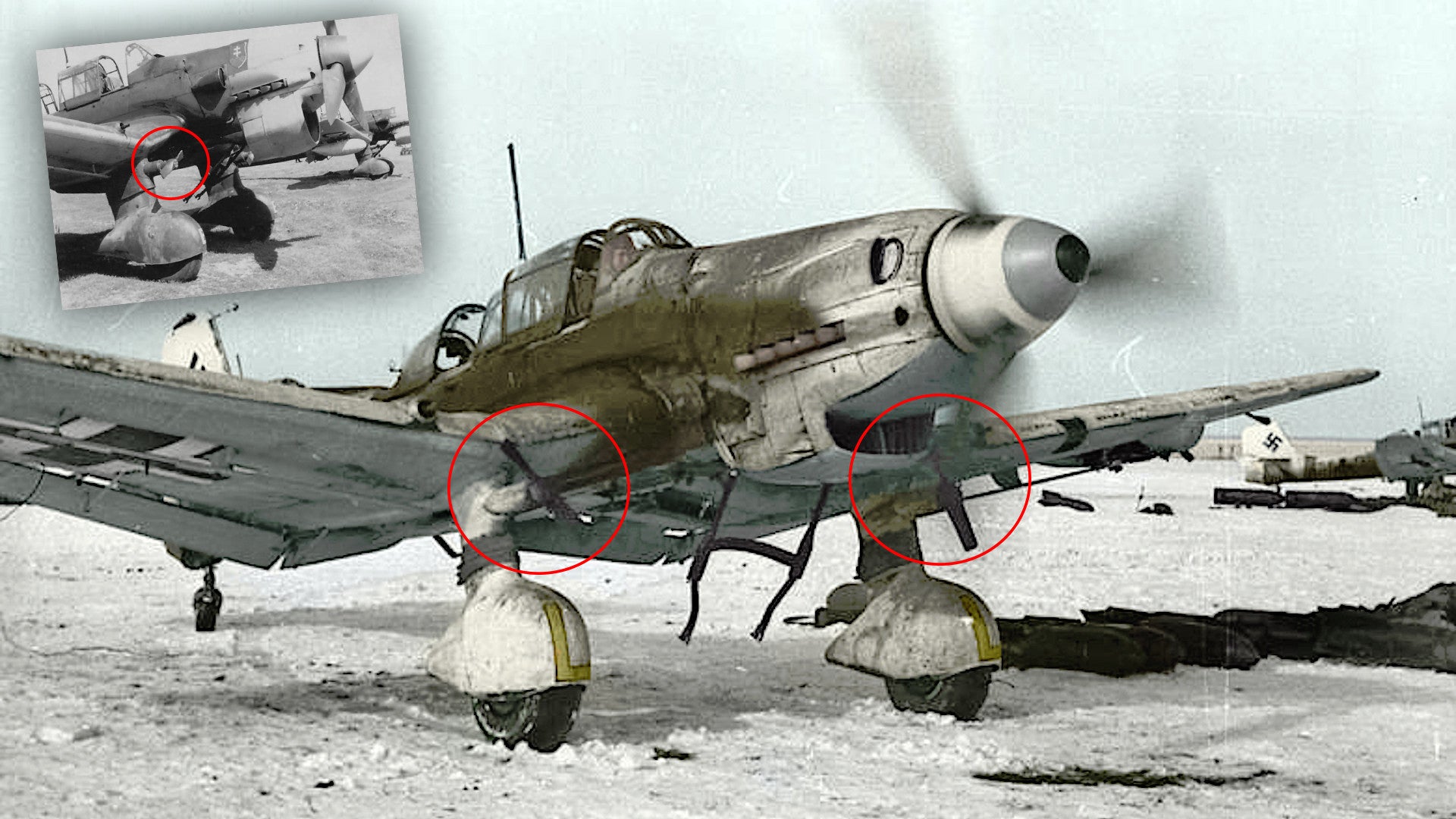

Quite reasonably, the CIA’s first thought was to see if the Air Force had a Ju-87 so personnel could examine the design of the original siren. The Stuka had two mounts, one on each of the fairings covering both of its fixed main landing gear struts, for what the Germans themselves had called Jericho Trompetes, or Jericho Trumpets. Both this and the CIA’s name for their device are references to the Old Testament story, also found in the Hebrew Bible, of the Israelites, under the command of Joshua, blowing rams’ horns to bring down the walls of the city of Jericho.

The Agency found that the Air Technical Intelligence Center did at one point have a Stuka, but had gotten rid of it and it was unclear where it had gone. “May now be in air museum or Army archives,” the officers writing up the Jericho Horn request noted.

CIA personnel also visited the Smithsonian Institution believing that it might have a complete Jericho Trumpet in its collection, but not on public display. As it turned out, the Smithsonian did not have one of the sirens and Paul Garber, then the Assistant Director of the Institutions Aeronautics Section told them to check with the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, Illinois, which, to this day, has a Ju-87 on display. Garber was also the first head of the National Air Museum, the predecessor to today’s National Air and Space Museum.

The handwritten report does not say what happened when CIA officials went to Chicago, but they would have been disappointed again. The aircraft there, which is a Ju-87R-2/Trop variant, is missing its landing gear fairings. The “Trop” in the designation refers to the aircraft’s tropical operations kit, which the German had developed for flying in hot and sandy environments, such as North Africa.

Trying to find Ju-87 with a working example of an original Jericho Trumpet would have been something of a wild goose chase. Junkers delivered more than 5,000 Stukas of all variants delivered to the Luftwaffe between 1936 and 1944, but the Nazis continued to send the increasingly obsolete aircraft into combat right until the very end of World War II. Today, just as it was when the CIA began their Jericho Horn project in 1958, there are just two effectively complete Ju-87s on display anywhere in the world, the one in Chicago and another at the Royal Air Force Museum in the United Kingdom. Various groups have or have had plans to restore other examples and there are a small number of partial aircraft in other museums, as well.

Given the difficulty of finding an original Jericho Trumpet, the CIA eventually went in a completely different direction. Starting in 1946, the U.S. government had initiated a secret program, known as Operation Paperclip, to relocate German scientists, engineers, and other technical specialists to the United States in order for them to work for the U.S. government and to keep them from doing the same for the Soviet Union.

The Agency identified Henning Von Girke, who had designed the original Jericho Trumpet, among the “Paperclips” working at the Air Force’s Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. Von Girke subsequently provided design notes and technical details regarding his siren.

Not everyone was thrilled with the Jericho Horn plan. In a meeting on May 12, 1958, another individual the CIA consulted, who’s name is redacted in the handwritten document, pointed out that the Ju-87’s iconic whine while diving actually came from its structural design and that the Germans themselves had only made limited use of the Jericho Trumpets, despite them being a popular point in any discussion about the Stuka. The trumpets added drag and slowed down the already sluggish dive bombers and alerted defenders that they were coming, all of which made the aircraft vulnerable.

This person also pointed out that the Navy had hired the Chrysler Corporation’s Dynamic Laboratory to develop a similar siren during World War II and that they had succeeded in crafting a superior design to German Jericho Trumpet. Unfortunately, testing on a Grumman F6F Hellcat propeller-engine fighter showed that the device made the plane dangerously unstable.

The Navy subsequently abandoned the effort, deciding that further development would not “be of significant value.” The individual also told CIA officials that they were “very doubtful [the] whistle will be of value.”

The CIA decided to continue with the project and in late 1958 had initiated a contract with an unknown company, the name of which is redacted in the declassified documents, to build four prototype Jericho Horns. The Agency initially estimated the cost of the project would be just $6,572 and that it would take three months to compete.

By the end of October 1958, the contractor working for CIA had built an experimental device with an air-driven whistle and begun putting it through testing in a laboratory enviornment. These tests showed that the device could generate a whistling sound up to 150 decibels loud. Measuring sound is difficult as it dissipates the further a person is from the source and how much an individual hears, to begin with, is highly variable. However, 130 to 140 decibels is typically considered the threshold for pain for most people. The CIA reported the potential to increase the siren’s output to between 170 to 180 decibels “by electronic means.”

Despite the initial projections, work on the siren continued at least into early 1959. The first series of flight tests involving a twin-engine Beechcraft AT-11 light aircraft carrying one of the Jericho Horns. It took place in January 1959.

The version employed in these tests had an adjustable “iris” for the whistle that would alter the air flow and change the sound output. Controls in the cockpit allowed the pilot to make these changes in flight. Despite the results of the ground testing, in six passes at 300 feet and at speeds of between 220 and 245 miles per hour, the AT-11-mounted siren only produced a maximum sound output of 108 decibels, about as loud as a chainsaw.

“In the present state this whistle can not be considered as a harassment item. It does however attract attention,” a CIA report on the flight tests said. “Upon hearing the whistle for the first time, and completely unaware that any such device was being tested, a charter pilot, who flew the undersigned to the test site, was of the opinion that either the oil or fuel pump of the test aircraft was failing. He expressed concern for fear the test aircraft might crash due to motor failure. Although this unbiased witness was concerned about the noise, he was not frightened to any degree.”

Another series of flight tests, utilizing a smaller Cessna Model 180, took place in March 1958 involving two different modified versions of the siren design with equally disappointing results. “At present the ‘Jericho Horn’ does not satisfy this requirement [for a psychological warfare device], and it is doubtful that continued effort will achieve this end,” a report dated Mar. 31, 1958, declared.

The CIA’s engineering division subsequently asked the Far East Division if there was any possible use to be had from the siren as a means of covertly identifying friendly aircraft flying above. Agency aircraft regularly conducted supply drops and other missions to support proxy forces or agent teams in hostile territory. Signaling to those planes could often be difficult and there was always an inherent risk of compromising personnel on the ground.

“If this whistle cannot serve any useful purpose as a psychological identification device, it is our recommendation that this project be dropped,” a Mar. 31, 1958 letter from the CIA’s engineering division said. “Two prototype whistles have been fabricated under this program and any recommendations as to their disposal would be appreciated.”

It’s not clear what ultimately happened to the two prototype Jericho Horns.

Interest in psychological warfare systems, including devices to generate annoying or painfully loud noises, never went away. During the Vietnam War, the U.S. Air Force experimented with an air-droppable device called the “Screeming Meemie,” with equally lackluster results. Aircraft and helicopters did carry speaker arrays to broadcast propaganda messages and obnoxious noises during that conflict.

The U.S. military famously blasted rock music at the Apostolic Nunciature, the Vatican’s embassy, in Panama City in December 1989, after the country’s autocratic ruler Manuel Noriega fled there following the U.S. invasion of the country. American forces took Noriega into custody after 10 days of negotiations and auditory harassment.

American law enforcement and military personnel employed similar tactics during the 1993 siege of the Branch Davian cult compound in Waco, Texas. This incident ended in a raid and the deaths of 76 individuals inside, including a number of children, and the U.S. government’s handling of the situation remains extremely controversial to this day.

Auditory psychological warfare definitely remains a part of U.S. military operations, with personnel on the ground using speakers or long-range acoustic hailing devices, or LRADs, to broadcast confusing, distressing, or otherwise harassing messages and noises. The War Zone

was first to report that American troops had played an audio recording described simply as “crying,” among others, during the campaign to eject ISIS terrorists from the Iraqi city of Mosul in 2016.

LRADs, in particular, have seen increasingly widespread use on the ground and at sea, and even aerial applications, typically mounted on helicopters, in the past couple of decades. Law enforcement agencies, as well as military forces, around the world have adopted them.

The U.S. Air Force, Navy, and Marine Crops also routinely use combat jets to conduct shows for force, relying in part on the psychological effect of the loud noise of those aircraft flying overhead at relatively low levels and high speeds, to ward off hostile or potentially hostile forces. The Air Force has employed other, larger fast-flying aircraft, including B-1B bombers and SR-71 Blackbird spy planes, in this role in the past, as well.

The sonic booms from the SR-71s, which were capable of flying at speeds more than three times the speed of sound, had a notable psychological effect on the countries the aircraft flew over, including Cuba, North Korea, and Libya. In 1990, in the lead up to the first Gulf War, Ben Rich, the head of Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works advanced projects division, specifically proposed reactivating a number of Blackbirds for operations over Iraq to both collect intelligence and “to sonic-boom the bastards.” The Air Force had retired these aircraft the previous year and passed on this pitch. It did return a number of these aircraft to service starting in 1995, before retiring the type for good in 1998.

Various branches of the U.S. military are now pursuing new technologies, including propaganda “leaflets” that can play recorded messages and balls of superheated plasma that can “talk,” that could expand the psychological warfare capabilities available to American troops. These developments could also benefit the U.S. Intelligence Community if agencies such as the CIA aren’t already pursuing their own efforts along similar lines.

However, it seems unlikely that the idea of attaching an air-driven siren to an aircraft to create loud and obnoxious noises while it flies at extremely low altitudes will ever make a comeback based on the CIA’s experience, as well as that of the Nazis themselves.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com