I had high hopes that the Pentagon’s Nuclear Posture Review would lay out a creative new strategy that would save money when it comes to sustaining and modernizing America’s hideously expensive nuclear arsenal. It ended up doing just the opposite.

Basically an “and the kitchen sink too” document, it not only maintains and modernizes the current nuclear triad, but also expands upon it with calling for new iterations of established delivery systems as well as a developing a whole new one as well. Most controversially it looks to field more “usable” nuclear weapons in some nebulous attempt to deter an enemy’s own use of low-yield tactical nukes during a limited conflict. This is sometimes referred to as “escalate to de-escalate,” but regardless of the tactics involved, really this document represents a handout to defense contractors of monumental proportions and above all else, a unsustainable and highly expensive strategy overall.

Just modernizing the nuclear arsenal we have today was slated to cost roughly $1.5T with inflation over the next 30 years and that is without the new initiatives laid out by the Strategic Posture Review. These include the introduction of low-yield warheads for the D5 Trident submarine-launched ballistic missile, the reintroduction of a nuclear-tipped naval cruise missile, and the development of nuclear-armed hypersonic weapons that will become a whole new medium of delivery in the coming decades.

Before the review was released the Pentagon was already working on new ICBMs, new Columbia class ballistic missile carrying submarines, new stealthy B-21 nuclear bombers, a new guided variant of the B61 tactic nuclear bomb dubbed the B61-12, and a new air-launched nuclear-tipped cruise missile dubbed the LRSO. Basically a totally remodeled nuclear arsenal along with all the command and control architecture that supports it. Now, according to the Strategic Posture Review and the Pentagon’s overall strategy going forward, this is not nearly enough.

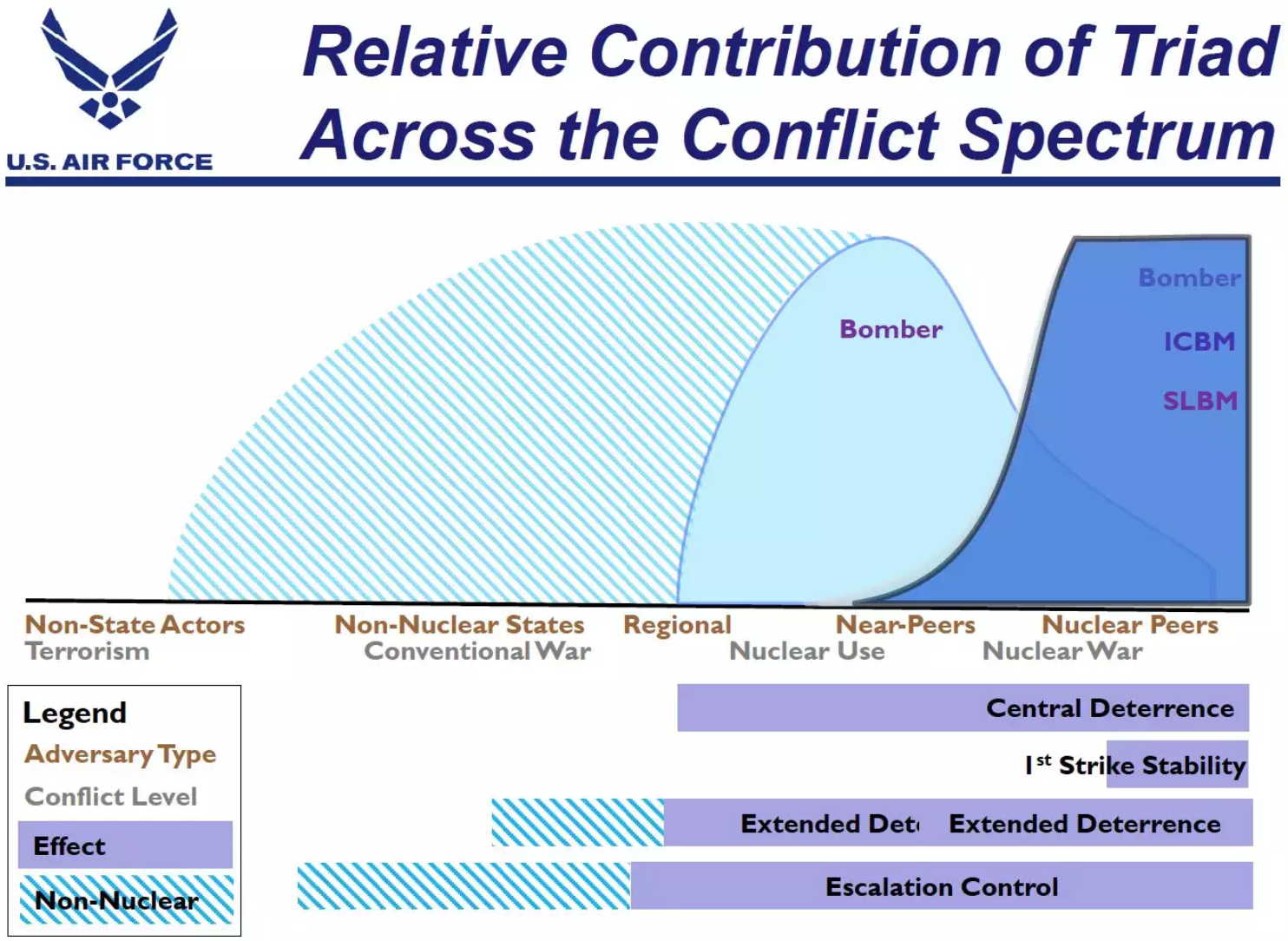

Many have argued, including the author of this article, for the potential elimination or reduction of the ground-based Minuteman III ICBM inventory in particular. This leg of the nuclear triad acts as a massive “nuclear sponge” to soak up hundreds of enemy warheads during a conflict more than anything else. This strategy is almost laughable if it weren’t so alarming. Maybe it would save the US from direct attacks on a number of secondary targets in populated areas, but what will be left of the US, or even the world eventually, once fallout from hundreds of thermonuclear weapons that pummeled the central part of the country takes effect.

The ICBM leg is not nearly as survivable as the ballistic missile submarine leg nor is it anywhere near as flexible as the nuclear bomber leg of the triad and its assortment of weaponry. Eliminating the ICBM leg of the triad could save hundreds of billions of dollars that could be invested in expanding America’s nuclear ballistic submarine force and on a whole slew of other capabilities the Pentagon says it desperately needs. Instead, under the Nuclear Posture Review, we are going to be sticking roughly 400 new missiles into existing Minuteman III silos.

Some will say that America’s ICBM force is “an insurance policy” against the other two legs of the triad experiencing technical failure or being knocked out before they can launch their deadly payloads. Considering that our second strike deterrent relies on those submarines primarily, such an argument is questionable at best. And by moving substantial funds to the nuclear ballistic submarine (SSBN) program, that second strike deterrent would only become more survivable and dense.

But even if the triad remains intact in full, do we really need to spend billions on new delivery systems beyond what was already planned? For instance, the nuclear tipped naval cruise missile seems to be more of a bargaining chip to get Russia back into treaty compliance than anything else, but that’s a very costly bargaining chip to say the least.

The nuclear-tipped BGM-109A Tomahawk cruise missile, usually referred to as the TLAM-N, was finally stricken from inventory just five years ago. Now a new missile would have to be developed for this purpose, and the procedures for handling and employing the weapon on American Navy ships and submarines would need to be reintroduced—a far more complex and expensive proposition than one might think.

Equipping Trident D5 submarine-launched ballistic missiles for tactical nuclear delivery purposes is downright troubling. An unannounced launch of Trident missile could, or more likely would, be viewed as an incoming strategic strike, not a limited tactical one. Quite frankly, such an act could usher in the beginning to the end of the world as we know it, especially during a time of such intense conflict that a nuclear weapon of any type would be used. The ability to issue a prompt tactical nuclear strike from nearly anywhere on the globe may be attractive, but hypersonic delivery systems will fulfill that capability in the years to come anyway, for better or worse.

In the end, substantially increasing the number of America’s nuclear delivery systems and making nuclear weapons “easier to use” is a reckless and extremely costly path to go down, especially without giving up something in return. And the cold hard truth is that $700B defense budgets are not sustainable. As America is forced to confront its reckless spending habits in the years to come, sustaining the nuclear arsenal we already have will become fiscally challenging—doing so with an expanded arsenal will be all but impossible.

So what you have here is a big reactionary shot of nuclear sugar before an inevitable crash. And yes, the threat profile may be changing around the globe, and certainly a resurgent Russia is something to be dealt with by fielding a strong defense and a solid nuclear deterrent, but how many ways do you need to potentially end the world multiple times over?

When it comes to tactical nuclear weapons, we already have hundreds of them forward deployed to Europe, and the F-35 would be a more cost effective and less risky delivery system than reintroducing naval cruise missiles or low-yield warheads on submarine-launched ballistic missiles. We will also have over 100 stealth bombers and 75 B-52s, not to mention a new very stealthy air-launched nuclear-tipped cruise missile to take on flexible nuclear delivery missions. So a bit of rationalization would go a long way when it comes to updating our nuclear arsenal instead of just saying “we want all of it and more.” Doing so isn’t a strategy at all, it’s a childish and irresponsible cop out to making realistic decisions that can endure for the decades to come.

So who wins in all this? Defense contractors, and in a huge way. Nuclear weapons contracts are extremely expensive and the secrecy surrounding them helps with limiting public ridicule and even congressional oversight.

But don’t blame the contractors, blame those who are making these decisions. Just going on a nuclear shopping spree while the dollars are many sets the Pentagon up for some tough, if not embarrassing triaging of fiscal priorities down the road. As such, the chances are very high that these initiatives will end up being viewed as highly wasteful and nearsighted in the not so distant future, and even integrating them into existing arms treaties is a whole other issue altogether.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com