As the possible transfer of Soviet-era MiG-29 Fulcrum jet fighters from the Polish Air Force to Ukraine continues to undergo twists and turns, it’s a timely reminder that getting hold of combat aircraft at very short notice can be by no means a straightforward affair. As one of the most capable Eastern bloc fighters of the late Cold War period, the MiG-29 has been in demand in the past, too. The story of how the United States ended up with no fewer than 21 Fulcrums back in the mid-1990s remains remarkable, but many aspects of it — including actually putting these aircraft to work — are still shrouded in secrecy.

By 1991, the breakup of the Soviet Union was complete, and well over a thousand MiG-29 fighters had been built. Indeed, the peak annual production rate of 228 single-seat aircraft and more than 50 two-seaters was reached in 1988. With the Soviet Union no more, huge numbers of military aircraft of all types were left outside Russia, the majority in Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan. As well as tactical jets, these three countries also all had long-range bombers left within their borders.

In Moldova, meanwhile, a newly independent country roughly half the size of West Virginia, the MiG-29s of the former Soviet Navy Black Sea Fleet air force were the most potent fighters available. Of the 33 jets this small nation inherited, 29 were examples of the then-latest 9.13 version, also known as Fulcrum-C, which Moscow had not yet made available for export and featured an active radar jammer in the spine. Another six were the earlier 9.12 model or Fulcrum-A, and the last six were two-seat MiG-29UB trainers. All were based at Mărculești in the northern end of the country. In contrast to the others, the Fulcrum-Cs had provision for the carriage and employment of nuclear weapons — normally a single RN-40 freefall bomb.

Unfortunately, Moldova, one of the poorest countries in Europe at the time, was in no financial position to maintain and fly its fleet of MiG-29s.

Moldova sold one MiG-29 to Romania in 1992, which acquired it to make up for a lost jet from its own Fulcrum fleet. In the same year, another Moldovan example was apparently shot down by a surface-to-air missile down during the conflict in the breakaway region of Transnistria, which had unilaterally declared independence from Moldova in 1990.

In 1994, Yemen had also descended into a civil war, fought between the pro-union northern state and the separatist socialist state in the south. The government here was also looking for new fighter jets and turned to Moldova, which reportedly loaned them 12 examples. Four of those jets ended up being sold to Yemen, while the others were returned.

By 1996, Moldova had put what was left of its MiG-29 fleet, 27 jets in total, up for sale. Few if any of these aircraft were likely in any sort of real operational service at the time.

At this point, the United States government entered the picture. The official line was that Washington was alarmed that the jets could end up being sold to Iran, which had already sent an inspection team to assess them. The United States stepped in and bought 21 of the Moldovan MiGs with an agreement signed accordingly in June 1997.

“It was on [Iran’s] shopping list,” then-U.S. Secretary of Defense William S. Cohen said of the Moldovan MiG-29 fleet. “And we are very happy to have them in our hands.”

The fee was undisclosed, but Cohen described it as “quite reasonable.” At the time, Reuters reported that the value of the package was around $40 million.

The funds for the purchase were provided by the Pentagon’s Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) program, an initiative that aimed to secure and dismantle weapons of mass destruction and their associated infrastructure in former Soviet Union states. This was relevant in this case since the 14 Fulcrum-Cs included in the delivery batch, unlike the six Fulcrum-As and the single MiG-29UB, were able to employ nuclear weapons, although none of these had been left on Moldovan territory. An off-the-shelf aerial nuclear delivery platform based on a late-generation fighter was a huge risk to have out on the open market, although Russian Minister of Defense Igor Sergeyev claimed that the jets were no longer nuclear-capable, the Soviet military having removed the relevant hardware back in 1989.

Nevertheless, returning this capability might not have been too difficult even if it was removed, although it’s far from certain that Iran would have attempted this, had it bought the jets. After all, Tehran had F-4 Phantom II and Su-24 Fencer aircraft that would have been far more suitable as nuclear-delivery platforms, as well as multiple missile platforms. Regardless, Iran already operated a fleet of MiG-29s and the Moldovan MiGs would have been a cheap and fast way to significantly upgrade their air combat power, despite any nuclear capabilities.

Between October and November 1997, the MiG-29s were prepared for transport by C-17A Globemaster III to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio. Along with the jets came spare parts and a significant haul of air-to-air missiles: 344 infrared-guided R-60 (AA-8 Aphid), 112 infrared-guided R-73 (AA-11 Archer), and 51 radar-guided R-27R (AA-10 Alamo) weapons.

Speaking at the time, Air Force Capt. Michael Davison, part of the 40-strong team recovering the jets, explained: “Not only couldn’t the Moldovans afford the fuel bill, they couldn’t keep up with the maintenance costs either. Their aircrews and maintainers hadn’t been paid for almost six months.”

“The Moldovans were shocked that we allowed enlisted technicians, especially women, to put their hands on the aircraft,” Davison added. “They just don’t do that there.”

From the start, the United States was interested in the capabilities of the jets, as well as keeping them from Tehran. Members of the Air Force’s Air Intelligence Agency were part of the team sent to recover them. Once the aircraft had been transported to the United States, they were examined closely by personnel from the National Air Intelligence Center (NAIC) at Wright-Patterson.

One item that was apparently singled out for particular interest was the MiG-29’s Soviet-standard identification friend-or-foe (IFF) system, likely the system codenamed Slap Shot by NATO. This allowed the MiG-29 pilot to interrogate similar systems to identify other aircraft or forces as friendly and would likely have revealed useful details about Soviet command and control networks.

The condition of the jets themselves left a lot to be desired, with at least some having been crudely over-sprayed in green paint while stored in Moldova. As of mid-1998, at least eight of these MiG-29s sat grounded and partially disassembled at Wright-Patterson, but the whereabouts of the other aircraft at this point was unclear.

At least some of the ex-Moldovan MiGs were returned to airworthiness and likely put through their paces, including in dissimilar air combat training (DACT) against U.S.-made jets. This would, of course, have provided valuable insight into the Soviet-made fighters, and especially the Fulcrum-C version, over and above what the NAIC engineers would have found in their ground-based investigations and from previous foreign exchange opportunities, exercises, and anecdotal firsthand reports. It’s even possible that a MiG-29 or two may have already been flying clandestinely for the Department of Defense at the time, but a whole fleet would provide an opportunity for expanded and more robust operations.

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Michael E. Ryan had confirmed that the service would fly a “few” of the ex-Moldovan jets in 1998. However, he denied that there were any plans to form some kind of aggressor unit, as some reports at the time had hinted might happen.

Years later, Smithsonian magazine reported that “a few Fulcrums that could be made flyable probably went to Edwards Air Force Base in California for testing,” although this cannot be confirmed.

On the other hand, a video from 2003 shows examples of both the MiG-29 and Su-27 over Groom Lake, Nevada, better known as Area 51. The clip below shows a MiG-29 flying with the Airborne Seeker Test Bed (ASTB), an adapted Gulfstream GII that’s used for research on radio-frequency and infrared sensors. It’s not clear whether one of the ex-Moldovan MiGs was involved, but it seems almost certain that the Fulcrum was being used to test and evaluate the performance of various sensors against it and to catalog its unique signature.

Since then, there have been further eyewitness reports of MiG-29s flying from Groom, with at least one observer noting that the aircraft involved were from the Moldovan stocks.

“I saw two -29’s on two consecutive days in November 2009,” an account on the area51trips blog explains. “The first was returning to Groom Lake over Queen City Summit, NV. The second was seen practicing intercepts with an F-16 over the Powerlines Overlook, before the pair flew directly over me back into Groom Lake Air Base. There is of course the possibility that I saw the same aircraft flying on each day.”

Again, it’s not clear how this 2009 identification was determined and there have certainly been several Fulcrums from other sources that have been flown in the United States, too, including examples from Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine that the U.S. also exploited for intelligence and possibly training value.

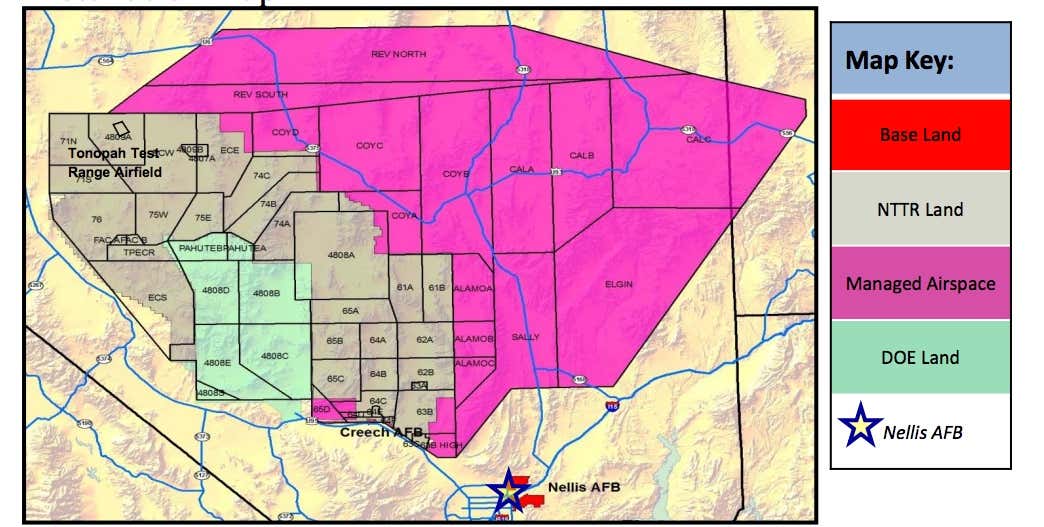

However, the practice of flying MiGs of different types against U.S. fighters was already well established as of the late 1970s and 1980s, albeit conducted under extreme secrecy. Most famously, the 4477th Test and Evaluation Squadron “Red Eagles” conducted these highly classified missions from the secluded Tonopah Test Range (TTR) airfield, which is situated within a corner of the Nevada Test and Training Range (NTTR). These activities allowed frontline U.S. fighter pilots to gain exposure to these valuable “assets.”

Up until roughly a decade ago, these programs remained highly classified and it’s certain they continue to this very day under new program iterations and that MiG-29s (and Su-27 Flankers) have been operated in a similar role more recently. In particular, the USAF’s prestigious Weapons School syllabus is rumored to still involve dogfights with 4th generation Russian fighter aircraft flying out of Groom Lake. While at least eight of the Moldovan MiGs are known to have ended up in museums and at various air bases around the United States, including at the Threat Training Facility at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada, it’s been reported that one or more of the others are still active in this clandestine adversary role.

According to a recent Air Force Magazine article, “some number” from the ex-Moldovan fleet continues to be flown to this day for DACT, alongside other Russian-made fighters. Spares from other non-flying members of the imported Moldovan MiG cadre also likely support additional Fulcrums used for clandestine testing and evaluation on behalf of the Department of Defense. With MiG-29s still flown by Russia, Iran, North Korea, Syria, and other potentially hostile states, providing pilots the opportunity to fly against them, and testing new sensors against them, remains relevant. This is in addition to just being able to fly against an unfamiliar threat aircraft in the flesh, which has its own significant experience advantages.

Not surprisingly, there is no official confirmation of this activity, and it remains the case that the rare sightings of MiG-29s flying in military airspace in the United States could be from sources other than Moldova or at least from a mish-mash aircraft acquired from various locales via over and covert means. There is also a tiny handful of these aircraft in private hands, but their use by the U.S. military has been extremely limited to non-existent. So the Moldovan jets, or parts of them, surely continue to play a role in helping prepare the Department of Defense for a potential confrontation with enemy Fulcrums. As such, the $40 million reportedly spent by the United States back in 1997 looks like very good value indeed.

Then again, many may be surprised or even angered that all the controversy over the transfer of NATO member-states MiG-29s to Ukraine is occurring while the U.S. itself is likely sitting on at least a few fully-capable fighters of the same type and vintage. Still, transferring these aircraft to Ukraine would eliminate a high-demand, low-density resource and it would probably require the disclosure of ongoing programs that the U.S. government would rather keep mum about.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com and tyler@thedrive.com